A version of the Competition Policy Council's recommendations was submitted to the Government of Canada's consultation on the future of competition policy in Canada.

On November 17, 2022, the federal government launched a long-awaited public consultation on the future of competition policy in Canada. As part of the consultation, the government released a discussion paper entitled The Future of Competition Policy in Canada, which covers a vast array of issues in Canadian competition law and possible policy responses. The government is seeking comments from stakeholders by March 31, 2023, which the C.D. Howe Institute’s Competition Policy Council is pleased to provide.

This is the first of two Communiqués the Competition Policy Council intends to release in response to the government’s consultation and discussion paper. The Competition Policy Council recognizes the importance of competition to Canada’s prosperity, and has a deep breadth of experience and a unique understanding of the role that the Competition Act, the Competition Bureau, the Competition Tribunal and other courts play in fostering competition in Canada.

This Communiqué focuses on the wider themes of the consultation. These include emphasizing the need for caution before departing from established Canadian law and process. The government should not seek to mimic developments in competition law and policy in foreign jurisdictions that are still untested, and instead rely on evidence in demonstrating the need for change. The companion Communiqué tackles the substance in the consultation paper itself and proposals from the Competition Bureau.

More broadly, the Council believes that the consultation on competition policy must look beyond the Competition Act. As one Council member and other authors have argued, “Focusing the ongoing consultative process only on the provisions of the Competition Act is far too narrow given the realities of overregulation in Canada.”

The Verdict: The consensus of the C.D. Howe Institute’s Competition Policy Council is that, beyond the consultation paper, more work and further consultation on specific proposals for reform to the Competition Act will ensure the government’s intention of promoting a competitive marketplace that favours prosperity and affordability for Canadians is properly reflected in legislation. Moreover, the consultation is only one step in a broader discussion on the future of competition policy in Canada, which should also look at other laws and policies that impact Canada’s competitiveness such as supply management, and limits on foreign ownership in sectors, such as telecommunications and aviation.

The C.D. Howe Institute Competition Policy Council comprises top-ranked academics and practitioners active in the field of competition law and policy. The Council provides analysis of emerging competition policy issues. Elisa Kearney, Partner, Competition and Foreign Investment Review at Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP, acts as chair. Benjamin Dachis, Associate Vice President of Public Affairs at the C.D. Howe Institute and Professor Edward Iacobucci, Competition Policy Scholar at the Institute, advise the program. The Council, whose members participate in their personal capacities, convenes a neutral forum to test competing visions and to share views on competition policy with practitioners, policymakers, and the public.

Canada’s Competition Consultation

As part of its deliberations on January 23rd, 2023, the C.D. Howe Institute Competition Policy Council discussed the ideal process for, and scope of, the consultation on the future of competition policy in Canada, as well as a perceived reliance on international developments as a justification for reform of Canada’s competition law framework.

The federal government formally began the process of reviewing competition law and policy in Canada on February 7, 2022,with a commitment to “carefully evaluate potential ways” to improve the operation of the Competition Act (the “Act”) in recognition of the Act’s critical role in promoting dynamic and fair markets.

On April 28th, 2022, the federal government introduced legislative changes to the Competition Act via Bill C-19, the Budget Implementation Act, 2022, with no public consultation. These changes received royal assent on June 23, 2022. The consensus view of the Council, provided in its June 2022 Communiqué, remains that the government missed key opportunities to consult with the various constituencies affected by the legislation. The Council’s principal position was that consultation would have improved the outcome of the legislative amendments and that the absence of consultation has resulted in a combination of amendments that could have been improved, unnecessary amendments, and uncertain amendments that could produce unintended consequences.

Focusing in on Specific Proposals

The consensus of the Council in this Communiqué is that the Consultation should not be the end of the conversation the government has on competition policy reform. There must be further discussion of, and consultations on, the particulars of reform. The government must continue to consult publicly in a timely fashion on the specific details of proposed changes to the Competition Act, including draft legislation. The details of legislative reform are essential to their effectiveness, and a process that again fails to invite comment on specifics would be an unnecessary mistake.

Expanding the Competition Conversation

In addition, the Council also achieved consensus on the conclusion that the conversation on competition must be broader than the Competition Act itself. Some of the issues raised in the Discussion Paper are items the government cannot remedy by amendments to the Act. The government must acknowledge the role of other policy decisions on the state of competition in Canada. It may be time to consult broadly with Canadians on government policies impacting Canadian competitiveness and examine the structural effect of sector-specific, standalone legislation outside of the Competition Act.

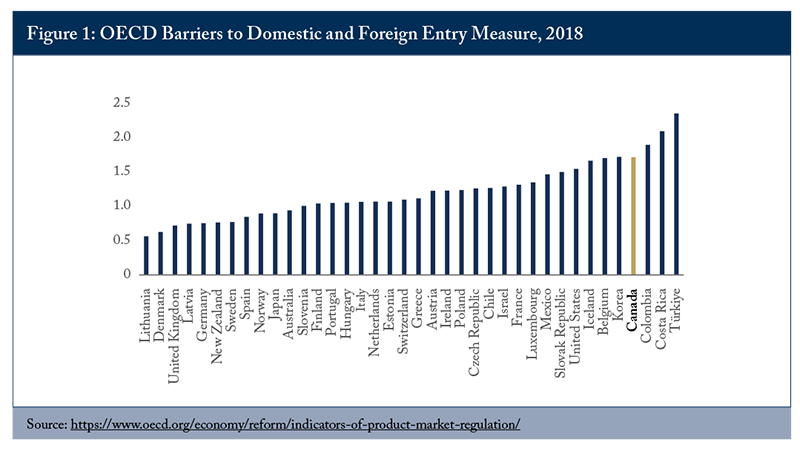

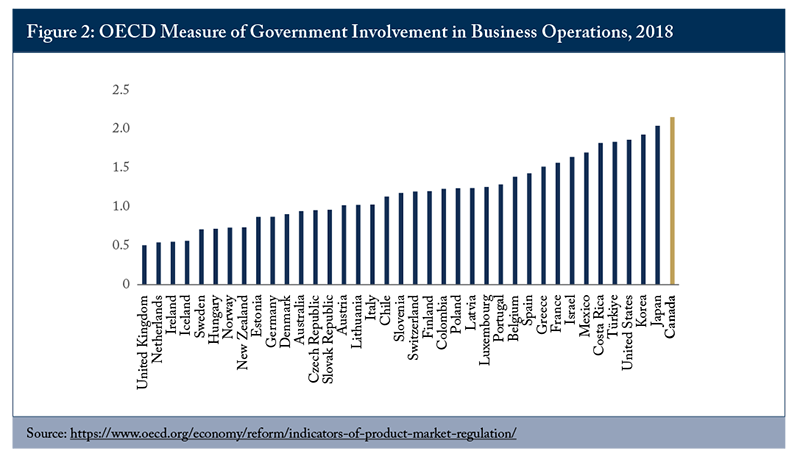

Canada has historically fared poorly in product market regulation measures conducted by the OECD, which assess the distortion of competitive markets by government policy. Among other OECD countries, only Colombia, Costa Rica and Turkey score worse in their level of barriers to domestic and foreign entry (Figure 1).

Foreign ownership restrictions are one significant type of sector-specific legislation in Canada. The Council notes that these limits apply in numerous areas, ranging from telecommunications, transportation, financial services, and others. Government limitations on entry affect postal services, supply-managed agriculture, and energy policy. Limitations on trade and mobility between provinces restrict entry by professionals and trades. In all these areas, government policies restrict competition and raise prices.

The conversation on competition policy should also extend to the provincial level by assessing the competitive effect of provincial regulations. For example, at a time of allegations of insufficient price competition in Canadian grocery retailing, and about the inadequacies of Canadian competition law to address these speculative concerns, governments have not yet turned their attention to anticompetitive supply management in Canadian agricultural markets. A number of Council members pointed to ideas and recommendations from the 2007-2008 Competition Policy Review Panel, many of which have not been implemented.

Adapting International Approaches to Canada

There was a consensus among Council members that the impetus to import international approaches to Canada with a view to harmonizing competition law globally would be a misstep. There is still great debate and no consensus on the benefits of the reforms that have been introduced or proposed in foreign jurisdictions. Indeed, the European Digital Markets Act will not come fully into force until 2024 and legislative amendments have yet to be passed in the United States. Companies and practitioners in foreign jurisdictions still do not have a full understanding of the impact of recent amendments and Canada has the opportunity to learn from experiences elsewhere.

Council members recognized that a thoughtful evaluation of approaches in foreign jurisdictions applied to the specific facts and circumstances of the Canadian economy and our legal and judicial frameworks could result in reform and the adoption of best practices from elsewhere. However, Council members emphasized that such a conclusion can only be reached after examining the evidentiary basis for the need for reform, specifically identifying the problem in Canada that the legislative proposal would be trying to solve and crafting a solution within Canada’s existing framework that works for the specific facts and circumstances of our economy.

Many Council members recognized the value of harmony in competition law and enforcement around the world and the role played by the Competition Bureau as an advocate on the international stage for the importance of competition law and policy. However, Canada should not abandon its principles-based, rather than rule-based, approach to competition law in the name of harmonization. For one thing, whether conduct is anticompetitive will typically depend on specific circumstances, and ex ante rulemaking will inevitably be based on assumptions and presumptions that are prone to false positives and false negatives. For another, fundamental principles of justice imbedded in our legal and judicial traditions differ from those in many foreign jurisdictions. Ex ante regulation, such as that being adopted in the European Commission, is rooted in civil rather than common law traditions. Outside of specific federally regulated sectors, ex ante regulation is not consistent with the common law approach. Proposals, such as those in the United Kingdom,

Bring on the Competition Reform Discussion

The C.D. Howe Institute Competition Policy Council welcomes the opportunity to consult with the government and other stakeholders on the future of competition policy in Canada and more specifically, on potential reforms to the Competition Act. However, process matters. The government must base future amendments to the Competition Act on a fulsome consultation on specific policy changes and legislative proposals. Moreover, the government should root all proposed changes to the Act in evidence demonstrating a need for change and not depart from established Canadian law and process simply by relying on untested developments in foreign jurisdictions with different legal traditions. Finally, the government should undertake a broader consultation on competition policy and the factors that impact the competitiveness of the Canadian economy.

Part II: The Pith and Substance of Reforms to Competition Policy in Canada

On November 17, 2022, the federal government launched a long-awaited public consultation on the future of competition policy in Canada. As part of the consultation, the government released a discussion paper titled “The Future of Competition Policy in Canada”

This is the second of two Communiqués the Council has released in response to the government’s consultation and Discussion Paper. The first Communiqué focused on recommendations for the consultation process and wider themes of the consultation, such as avoiding reliance on untested international developments in competition law and policy for making the case for reform of Canadian policy.

The Verdict: The Discussion Paper offers numerous proposals for competition law and policy reform in Canada and for the Competition Act

The Council comprises top-ranked academics and practitioners active in the field of competition law and policy. The Council provides analysis of emerging competition policy issues. Elisa Kearney, Partner, Competition and Foreign Investment Review and Litigation at Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP, acts as chair. Benjamin Dachis, Associate Vice President of Public Affairs at the C.D. Howe Institute and Professor Edward Iacobucci, Competition Policy Scholar at the Institute, advise the program. The Council, whose members participate in their personal capacities, convenes a neutral forum to test competing visions and to share views on competition policy with practitioners, policymakers, and the public.

Administration and Enforcement of the Law

Purpose of the Competition Act

The overarching question in the consultation is whether Canada’s competition policy framework is fit for purpose. Policymakers in Canada and around the world are under pressure to address a broad scope of social policy issues such as income inequality, privacy, and environmental protection. The pressure is being felt, too, by competition law agencies, as advocates for competition policy reform are seeking to expand the purpose of competition law to advance non-economic social policy objectives notwithstanding the often tenuous link between competition and these other goals.

The current goals of the Act are economic in nature, including the promotion of economic efficiency, expanding exports, supporting small- and medium-sized enterprises, and providing consumers with competitive prices and product choice. To many Council members, it would be a mistake to expand the already long list of objectives under the Act to advance non-economic social policy objectives. Introducing too many goals risks confusion in the application of the law; which goal will prevail when goals point in opposite directions? Expanding the purpose of competition law also invites results that do not sit well within competition law. For example, an anticompetitive merger that reduces output, and hence carbon emissions, may be welcome from an environmental perspective, even if it produces anticompetitive effects on the prices charged and products offered to Canadian consumers. Moreover, assigning disparate goals to competition law undermines competition law enforcement and challenges the independence of the institutions. With disparate policy goals, whose job is it to select which goal should prevail: policymakers, the Bureau, or the judiciary?

The Council’s view is that the Bureau, the agency that enforces Canada’s competition policy framework, should remain focused on its principal mandate of promoting competition and leave the task of advancing social policy objectives to others in government that have political accountability or the necessary policy tools and expertise available to them.

Under the assumption that the objectives of the Competition Act have for the most part not changed, a position the Council endorses, the Discussion Paper focuses on how the substantive provisions of the law could be improved

The Competition Policy Council has tackled the questions of whether competition law has the teeth to oversee the digital marketplace, arguing that that the Bureau largely already has the “toolkit” to handle big tech.

An Ex Ante Regulatory Approach to Competition Law Enforcement

The introduction of ex ante rules into Canada’s competition policy framework would transform the Bureau from a competition law enforcement agency to a sector-specific regulator, and would be a significant departure from the existing sector-neutral, principles-based approach to enforcement of the Act. There are numerous sector-specific regulators in Canada, such as the Canadian Radiotelevision and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC), the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI), and the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC), that enforce ex ante rules or mandatory codes of conduct. By contrast, the Bureau is not a regulator; the Bureau is an independent law enforcement agency.

The consensus view of the Council, emphasized in the first Communiqué responding to the consultation, is that there are amendments that can be made to improve the effective enforcement of Canada’s competition policy framework before resorting to a regulatory approach.

Enforcement decisions of the Commissioner, who is appointed by the Governor-in-Council, are not subject to ministerial review or approval. The Council supports and agrees that independence of the Bureau is important. However, many Council members believe that the Commissioner should be held accountable for his budgetary spending, as well as the Bureau’s enforcement and advocacy actions. This could take many forms, including by way of regular reports to, and appearances before, Parliament; expanded annual reporting requirements that incorporate value-for-money audits; or even the creation of an ombudsperson role for civilian oversight, which would mirror other independent federal law enforcement agencies. Many Council members agreed that more ex post assessments of Bureau enforcement decisions (similar to a US FTC merger remedies study) would be a productive use of resources. Regardless of the method chosen, the Council recommends that to achieve the government’s intended goal of more effective enforcement of competition law, greater duties of transparency and accountability should accompany any additional increases in funding or first instance decision-making authority (discussed further below).

Expansion of Investigative Powers and First Instance Decision Making

With respect to expanded investigative powers and first instance decision-making authority, Council reached a strong consensus view that the process for the Bureau to obtain a section 11 to compel the production of information – an ex parte hearing before a judge – is already streamlined, and that easing the burden on the Commissioner in the enforcement context raises issues of procedural fairness. Indeed, the necessity of the current section 11 process to protect parties from overly onerous document demands is evident from a 2008 Federal Court decision overturning the grant of a section 11 order after the parties raised concerns about the repetitive and onerous nature of the Bureau’s demands.

Council members also expressed concern with proposals in the Discussion Paper to grant “first-instance ability to authorize or prevent forms of conduct” to the Bureau.

The Council remains divided on the issue of whether the Bureau should be engaged in market studies. Some members continue to believe that market study powers are an important aspect of advocacy by the Bureau and recall that the Competition Policy Review Panel’s 2008 report concluded that the lack of a formal ongoing process to undertake competition advocacy, including market studies, constitutes a “significant gap in Canadian competition policy.”

A general consensus was reached that the use of any market study power must be reserved for appropriate cases and should incorporate procedural safeguards and accountability measures. Suggestions for procedural safeguards and accountability measures include having specific budget requests for market studies approved by Treasury; having the terms of reference for any market study approved by a Parliamentary committee; and having judicial oversight on the scope of any documentary production.

In addition to investigative powers, Council members agree that how cases are initiated is also an important consideration for effective enforcement of competition law. In this regard, the Council has long argued for reforms to private access for enforcement of the Act. In its fall 2016 Communiqué on the topic of private rights of action,

The Council supports the amendments in the 2022 budget implementation legislation (the “BIA Amendments”) to supplement public enforcement and hold firms more accountable by allowing private parties to bring cases before the Tribunal for abuse of dominance.

Some Council members believe that the significant increase in fines for abuse of dominance introduced by the BIA Amendments risks creating “private sheriffs” where competitor-driven complaints may result in the Tribunal levying disproportionate fines against parties, leading to risks of over-deterrence. However, the majority opinion among the Council is that the BIA Amendments failed to provide adequate incentives for private parties to bring cases forward. The general consensus of the Council is that properly incentivizing private access to the Tribunal (with safeguards against vexatious and frivolous litigation) would help both in enforcing the Act and in generating greater case law and guidance regarding the application of the Act for the Bureau, the legal community, and businesses. Former Council member Peter Glossop argued in a June 2022 C.D. Howe Institute Intelligence Memo that “there is no compelling reason to deny a private firm full compensation for anti-competitive harms suffered because of an abuse of dominance.”

Merger Review

The Discussion Paper raises the risks of excess corporate consolidation and of reviewing too few mergers or doing too little to prevent anti-competitive activity and discusses potential areas of improvement, from enhanced pre-merger notification and detection, through limitations on the Bureau’s ability to act (such as conditions on interim relief and the remedial standard), to the defences available to merging firms (such as the efficiencies defence).

The Council supports “the revision of pre-merger notification rules to better capture mergers of interest”

Council members agreed that careful study should be given to whether the monetary thresholds are at the appropriate level to capture transactions most likely to raise competition concerns and act as a deterrent to anti-competitive mergers.

Proposals made by certain Council members to address over-reporting include, but are not limited to: (i) removing the asset threshold from the notification test (though not all Council members agreed on this, as some Council members were able to identify high-asset value transactions that raised issues where the revenues were less than the asset values); (ii) excluding transactions where the purchaser (together with its affiliates) does not have a presence in the Canadian market; and (iii) eliminating vendors from the size of parties threshold where the vendor is divesting its entire interest in the business.

Many Council members argued that as total manufacturing in Canada declines, supply chains across countries integrate, and intangible products and services (e.g., digital products and internet-based services) play an increasingly important role in the Canadian economy, merger review should likewise shift to focus on potential effects on Canadian consumers, irrespective of the location of the target’s operations. Council members debated the merits of an amendment to the current pre-merger notification regime whereby (a) mergers in which the target only sells goods or services into Canada, but does not itself have assets in Canada, are not subject to pre-merger notification and (b) the revenues taken into account for the size of transaction threshold are restricted to those generated by Canadian assets. Council members who supported an amendment said that it could be accomplished by including sales “into” Canada in the Size of Transaction threshold test at section 110 of the Act, similar to the test used in section 109. Another Council member argued that the financial metrics on which the thresholds are based are themselves outdated, and that additional thresholds could be considered that are likely to capture firms that have a significant anticipated future market position, such as by adopting an alternative enterprise value threshold test.

Certain Council members argued in response that not giving the Bureau jurisdiction to review acquisitions on the basis of sales into Canada alone is justified because of the inability to enforce a remedy absent assets in Canada and that such cases would likely be addressed by enforcement in other jurisdictions.

Many Council members support the use of exemptions from pre-merger notification for sectors such as real estate, upstream oil and gas, and certain financial services transactions that rarely give rise to competitive concerns, as a method to better calibrate the set of transactions subject to pre-merger notification. However, other Council members, while supporting consideration of further exemptions, stated that exemptions must be closely considered and carefully drafted to avoid being overly inclusive. Council members have numerous other suggestions for reform to better capture mergers of interest, including introducing aggregation rules and the application of the pre-merger notification provisions to non-corporate joint ventures and joint acquisitions by a special purpose vehicle where no shareholder holds more than a 50 percent interest. Given the technical nature of pre-merger notification, the Council recommends that the government strike a Bureau-bar working group to advise on technical amendments.

The Discussion Paper seeks views on extending the limitation period in which the Bureau can challenge all mergers from one year to three years post-implementation, or extending the limitation period for non-notifiable mergers, or tying it to voluntary notification.

Council members agreed that addressing the current weaknesses of Part IX of the Act will go a long way to rebalancing the merger notification regime. One Council member recommends pairing modernization of the pre-merger notification thresholds with amendments that enhance the Bureau’s ability to identify potentially problematic non-notifiable mergers. More specifically, the Council member recommends that the limitation period to challenge non-notifiable mergers be extended to three years but not longer, since lengthening the period between when a merger is closed and when it is investigated and challenged decreases the certainty that the merger is the cause of any anti-competitive conduct identified in a market. Three years would apply unless the transaction has been voluntarily notified to the Bureau prior to closing, in which case, the one-year limitation period should continue to apply.

Some Council members spoke in favour of the logic of extending limitation periods for all mergers, especially as a substitute for other, more distortive, recommendations such as a lower standard for intervention or the introduction of structural presumptions and burden shifting, as discussed below. However, several Council members raised concerns that calls for extended limitation periods were in reaction to transactions that posed no problems when they were completed, but with hindsight became viewed as problematic years later as the relevant markets evolved, potentially conflating effects in the market with effects of specific transactions.

Modifying the Legal Test and Remedy Standard

The Discussion Paper raises a number of proposals to address the possible substantive challenges to applying the merger provision’s competitive effects test to acquisitions in fast-moving digital markets. These include introducing a more flexible definition of likelihood such as “an appreciable risk of materially lessening competition,” reversing the burden of proof, introducing presumptions for already dominant firms, and special tests for platforms.

Council members expressed a range of views on these proposals. There was little support for introducing a more flexible definition of likelihood. Similarly, Council members believe that changing the standard to a “balance of harms approach” would create legal uncertainty. Many Council members pointed to the information asymmetry that exists between the merging parties and the Bureau, as the Bureau has statutory powers to compel information from third-party market participants through its use of section 11 orders; without access to the same information, structural presumptions and reversed onus will be difficult for the merging parties to respond to. If bright-line tests or rebuttable presumptions are introduced, the consensus view of the Council is that the due process rights of merging parties would have to be protected by giving the merging parties access to the information collected by the Bureau during the section 11 process.

Some Council members expressed scepticism on the benefit of structural presumptions noting that rebuttable presumptions are already present within the Bureau’s merger enforcement practice.

Council members more supportive of the introduction of rebuttable presumptions noted that presumptions could assist the Bureau in capturing marginal mergers in highly concentrated industries while preserving its enforcement resources. However, others pointed out that introducing presumptions would merely shift the debate and analysis (and associated enforcement resources) to market definition.

To address concerns about market concentration, the Bureau has recommended that the standard for remedy proposals be changed from restoring competition to a level that is not substantially less than it was before the merger to restoring competition to the level that would have prevailed but for the merger.

Council members also challenged the lack of empirical evidence supporting the recommendation that the remedial standard required revision to address anti-competitive effects from mergers. The Council encourages the government to give the Bureau resources to engage in a retrospective merger remedies study before revising the remedial standard.

Council members support the importance of efficiencies in merger analysis and generally agree that the consultation is an opportunity for Canada to reconsider its approach to the efficiencies defence, which applies if cost savings in a merger outweigh negative impacts on competition.

There was, however, no consensus reached by the Council on substantive changes to the efficiency defence to improve its effectiveness, whether considering efficiencies within the competitive effects test rather than as a full defence, shifting the elements or procedure required for establishing or contesting efficiencies, weighting the factors differently or fully adopting a consumer surplus standard in line with the United States and other foreign jurisdictions, or increasing the role of unquantified evidence. There was little support amongst Council members for limiting the application of the defence only to mergers or markets with certain characteristics.

Some members of the Council continue to believe that the efficiencies defence is an important aspect of Canada’s framework legislation, designed to permit a merger in rare instances where there is an increase in the efficiency of the Canadian economy, whether by lower costs or increased output, that outweighs harm from reduced competition or higher prices.

Unilateral Conduct/Abuse of Dominance

The Discussion Paper raises questions about the efficacy of Canadian competition law enforcement in the event of anti-competitive conduct by dominant platforms in the digital economy, acknowledging, however, that their size and success is due in part to “innovation and producing compelling goods and services.”

The Council rejects the premise that big is necessarily bad and encourages the government to examine the evidentiary basis for reform. Nevertheless, Council members discussed: crafting a simpler test for a remedial order, including revisiting the relevance of intent and/or competitive effects; creating bright-line rules or presumptions for dominant firms or platforms; and condensing the various unilateral conduct provisions into a single, principles-based abuse of dominance provision. There is very little support amongst Council members for designing unilateral conduct provisions outside of abuse of dominance to address “fairness in the marketplace.” The Council is of the view that competition law enforcement should remain focused on protecting competition; not protecting competitors.

With the exception of per se criminal provisions to address hard-core cartel conduct, competition law enforcement in Canada involves ex post facto assessment rooted in economic evidence of harm or potential harm to competition. Council members continue to support such an approach.

The Council has been calling on the government to amend the legislation on abuse of dominance to protect against harm to competition in general, rather than harm against particular competitors as had been interpreted by the courts since 2016.

Specific Council members have addressed important issues such as the relevance of “intent” and the meaning of “substantial lessening of competition” in their personal capacity. They cover important issues that bear emphasizing. For example, Professor Edward Iacobucci in his September 2021 paper, “Examining the Canadian Competition Act in the Digital Era” supported removing the intent requirement from section 79(b) of the Act and relying on demonstration of anti-competitive effect.

Recognizing the inherent difficulty in moving quickly to prohibit conduct that may have an anti-competitive effect, given the time needed to investigate and adjudicate cases with complex factual determinations, some Council members encouraged the government to consider what additional tools may be available to streamline investigations and resolutions, while ensuring important due process and rights of defence. For example, Council members considered the addition of alternative dispute resolution and final offer arbitration in the toolkit of possible competition law remedies.

Council members emphasized that enforcement based on structural presumptions and bright line tests may, just like enforcement that moves too slowly, also result in irreversible anti-competitive market outcomes. False positives (i.e., over-enforcement) and false negatives (i.e., under-enforcement) both have negative repercussions on the economy and on Canadians. The Council does not agree that recent legislative proposals and reforms abroad (e.g., the European Union’s Digital Markets Act), which appear to be more concerned with marketplace fairness and protecting competitors than with competition, would be appropriate for Canada. Bright line rules against self-preferencing, in which a dominant firm favours its own downstream products and thereby hurts competitors – but not necessarily competition – reflect this tendency. Given that many forms of unilateral conduct enhance competition or are competitively benign, the majority view of the Council is that it is in the interests of a dynamic, innovative, and competitive economy that the abuse of dominance provisions, whatever their ultimate form, remain focused on effects.

Condensing Unilateral Conduct Provisions

The Council has previously considered the merits of consolidating various civil provisions dealing with single firm conduct (refusal to deal (section 75); resale price maintenance (section 76); exclusive dealing, tied selling and market restrictions (section 77); and abuse of dominance provision (section 79)) into a single provision. Each of these sections addresses conduct that can be pro-competitive, competitively benign, or anti-competitive, depending on the facts. Nevertheless, different conduct is subject to different thresholds for determining harm (such as adverse effect on competition or substantial lessening of competition), procedural routes (private access for certain provisions and not others), and potential remedies (including administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) for abuse of dominance, but only prohibition orders for other provisions), creating complexity and uncertainty for businesses trying to comply with the Act.

In its spring 2016 meeting,

The Case For Consolidating Reviewable Practices

A number of Council members would support some or all of the three specific reviewable practices (sections 75, 76, and 77) being subsumed under the more general section 79 – with significant support for consolidating section 77 in particular – on the basis that different standards increase the risk that cases may be brought by the Commissioner under a given provision to gain a strategic advantage. A single threshold would also create more consistency within the Act. For example, consolidating section 77 into 79 would also capture restrictive covenants imposed by a customer on its supplier (i.e., monopsony behaviour) which it does not today. One Council member argued that the conduct not already covered by section 79 should be captured by an expanded section 90.1, as discussed below.

The Case Against Consolidating Reviewable Practices

However, a number of Council members felt that amendments should seek to improve clarity instead of merely amending the Act for the sake of symmetry, and favoured retaining the specific provisions for refusals to deal and price maintenance with lower thresholds for harm but no AMPs, particularly given the cumulative jurisprudence that already exists. Some Council members expressed concern that eliminating specific provisions on price maintenance would put Canada too far afield of competition practices globally with others noting that Canada’s price maintenance provisions were already different than our main trading partner.

Competitor Collaborations

The Discussion Paper considers measures to improve the effective enforcement of both per se criminal offences for “hard core” cartel activity as well as civil competitor collaborations, including making it easier to infer an agreement and examining past conduct in the civil context, and reintroducing buy-side collusion – beyond the BIA Amendments – to the criminal bucket.

One particularly concerning proposal in the Discussion Paper questioned whether concepts such as “agreement” and “intent” should continue to apply when considering the actions of machine learning algorithms, and referring to fundamental principles of criminal law such as mens rea as “evidentiary obstacles” to Bureau investigations.

It is well-established that buy-side coordination can have positive impacts on competition by allowing smaller players to align purchases, reduce transaction costs, promote efficiency, and improve outcomes for consumers. There was consensus at the Council that expansion of the criminal conspiracy provisions to capture buy-side collusion, beyond existing provisions addressing naked wage-fixing and no-poaching agreements, is unnecessary and duplicative. The Council continues to believe that “criminal law is too blunt an instrument to deal with agreements between competitors that do not fall into the hard core cartel category.”

Given the relatively low success rate the Bureau has had in detecting, investigating, and ultimately prosecuting hard core cartels, some Council members believe that the Act’s criminal cartel provisions should be complemented by civil provisions, as is done for deceptive marketing. This would allow the Bureau to elect whether to pursue the conduct criminally or civilly.

The Council discussed a number of ways that enforcement of the civil competitor collaboration provisions could be improved, as explained below.

Harmful Collaboration Between Firms that are Not Direct Competitors

Section 90.1 currently covers only agreements or arrangements “between persons two or more of whom are competitors.”

One Council member argued that the elimination of the “competitor” requirement would (i) ease enforcement by making the application of section 90.1 simpler and more effects-driven; (ii) improve compliance incentives by allowing market participants to focus only on the potential effects of their agreements; and (iii) further align competition law in Canada with the laws of significant trade partners, such as the United States and the European Union, which have simpler prohibitions against anti-competitive agreements.

Other Council members believe there is not a clear case for the application of section 90.1 to vertical agreements, and that the pro-competitive benefits of vertical integration make the extension of the application of the law unnecessary.

Deterring Competitor Collaboration With Stricter Penalties

Some Council members are of the view that the imposition of an AMP with respect to the competitor collaboration provisions would improve the Act’s effectiveness. Other Council members cautioned against the imposition of AMPs for agreements that are generally considered presumptively legal.

The Discussion Paper also proposes to expand the scope of civil enforcement to prior conduct, in addition to ongoing and future conduct which is already caught. The Discussion Paper raises the concern that the inability to capture past behaviour could incentivize continuation of the behaviour until forced to stop. Discussion Paper notes that the current approach “is consistent with the civil approach to protect markets rather than discipline its actors.”

For example, Council members discussed the availability of private rights of action for anti-competitive competitor collaborations, whereby third parties could seek damages and/or the ability for the Tribunal to make a restitution order.

Unfortunately, competition law compliance is not always straight-forward. Many factors go into assessing the likely effect of a commercial agreement on competition. In most cases, the Bureau is best placed to assess the likely or actual effect of a commercial agreement on competition because of its power to collect information from third parties, either on a voluntary basis or through the various information collection powers available to it under the Act.

Council members also discussed a voluntary notification system that would provide a statutory exemption from AMPs where a firm (or firms) notifies the Bureau of proposed conduct (under any section of Part VIII of the Act, including competitor collaborations) before implementation. This would allow the Bureau to engage in a proactive assessment of potential effects and, if needed, impose a proactive remedy (in accordance with the enforcement powers currently available to the Tribunal). As a result, the firm (or firms) would not face adverse consequences, other than the imposition of a prohibition order (as is currently provided for under Part VIII), if it were later determined that the impugned agreement prevents or lessens competition substantially.

To encourage participation, a prior notification regime should exempt parties from AMPs that might otherwise be available to remedy anti-competitive conduct, and the Bureau should establish reasonable service standards within which parties can expect the Bureau to complete its review of voluntarily notified matters.

However, many Council members are of the view that the advisory opinions provision contained in s.124.1 already provides for a voluntary notification system, which is currently ineffective and underutilized. Rather than introduce a new regime, these members argued that the Commissioner should be obliged to issue an advisory opinions (i.e., change “the Commissioner may” to “the Commissioner shall”) within a reasonable statutory deadline.

Council members agreed that it is important that the Act not serve as a deterrent to commercial agreements that are not anti-competitive. It will be important for the government to strike the right balance.

Conclusion

The federal government’s review of Canada’s competition policy framework affects all businesses. As the Competition Policy Council emphasized in its first Communiqué responding to the Discussion Paper, how the government conducts the review will be a signal of what kind of legal and regulatory climate businesses face in Canada. Similarly, amendments made in an effort to improve the effectiveness of the Act could inadvertently chill innovation and distort competition. The government recognizes this in its desire to create a principled, evidenced-based approach to competition law, policy and practice that balances the need to encourage innovation and the need to ensure a level competitive playing field. The many issues that this second Communiqué addresses showcases the extent to which there is much to consider in trying to achieve the desired balance. The Council looks forward to further discussion with the government.

Members of the Council participate in their personal capacities, and the views collectively expressed do not represent those of any individual, institution or client.

- *George N. Addy, Chair Advacon Inc. Director of Investigation and Research, Competition Bureau, 1993-1996.

- Melanie Aitken, Managing Principal, Washington, Bennett Jones LLP. Commissioner of Competition, Competition Bureau, 2009-2012.

- *Marcel Boyer, Research Fellow, C.D. Howe Institute. Professor Emeritus of Industrial Economics, Université de Montréal, and Fellow of CIRANO.

- Tim Brennan, International Fellow, C.D. Howe Institute. Professor Emeritus, University of Maryland Baltimore County. T.D. MacDonald Chair of Industrial Economics, Competition Bureau, 2006.

- *Neil Campbell, Co-Chair, Competition and International Trade Law, McMillan LLP.

- Erika M. Douglas, Assistant Professor of Law, Temple University, Beasley School of Law.

- Renée Duplantis, Principal, The Brattle Group. T.D. MacDonald Chair of Industrial Economics, Competition Bureau, 2014.

- Calvin S. Goldman, K.C. The Law Office of Calvin Goldman, K.C. Director of Investigation and Research, Competition Bureau, 1986-1989.

- *Jason Gudofsky, Partner, Head of the Competition/Antitrust & Foreign Investment Group, McCarthy Tétrault LLP.

- *Lawson A. W. Hunter, K.C., Senior Fellow, C.D. Howe Institute. Counsel, Stikeman Elliott LLP. Director of Investigation and Research, Competition Bureau, 1981-1985.

- Susan M. Hutton, Partner, Stikeman Elliott LLP.

- Edward Iacobucci, Professor and TSE Chair in Capital Markets, University of Toronto. Competition Policy Scholar, C.D. Howe Institute.

- *Paul Johnson, Owner, Rideau Economics. T.D. MacDonald Chair of Industrial Economics, Competition Bureau, 2016-2019.

- Navin Joneja, Chair of Competition, Antitrust & Foreign Investment Group, Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP.

- Elisa Kearney, Partner, Competition and Foreign Investment Review and Litigation, Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP. Chair, Competition Policy Council of the C.D. Howe Institute.

- Michelle Lally, Partner, Competition/Antitrust & Foreign Investment, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP.

- *John Pecman, Senior Business Advisor in the Antitrust/Competition & Marketing at Fasken. Commissioner of Competition, Competition Bureau Canada, 2013-2018.

- *Margaret Sanderson, Vice President, Practice Leader of Antitrust & Competition Economics, Charles River Associates.

- The Hon. Konrad von Finckenstein, Senior Fellow, C.D. Howe Institute. Commissioner of Competition, Competition Bureau, 1997-2003.

- Omar Wakil, Partner, Competition and Antitrust, Torys LLP.

- *Roger Ware, Professor of Economics, Queen’s University. T.D. MacDonald Chair of Industrial Economics, Competition Bureau, 1993-1994.

- *The Hon. Howard Wetston, Senior Fellow, C.D. Howe Institute. Senator for Ontario since 2016. Director of Investigations and Research, Competition Bureau, 1989-1993.

- Ralph A. Winter, Canada Research Chair in Business Economics and Public Policy, Sauder School of Business, University of British Columbia.

*Not in attendance on January 23, 2023.