Study in Brief

• With protectionism on the rise, Canada needs a national supply chain strategy to increase the efficiency and resiliency of its supply chains in the face of future global shocks and internal hazards.

• Canada’s prosperity is at stake. Well-functioning supply chains are key to addressing problems such as affordability, competitiveness and security, whose resolution is key to raising Canadians’ standards of living.

• While other countries have launched national supply chain strategies, Canada has been a laggard – despite the growing threats presented by tariffs and other protectionist strategies, as well as other risks to the free movement of goods, including strikes and blockades, natural disasters, outbreaks of disease, cybercrime, sabotage, and wars. A focused supply chains strategy would place Canada in a much better position to respond to these threats.

• This Commentary sets the global scene, discusses how to capture the benefits and minimize the risks associated with supply chains, and provides a blueprint for the goals and elements of a national supply chain strategy for Canada. The blueprint includes recommendations on securing critical supplies, on infrastructure priorities and related regulatory reforms, on trade alliances and countering protectionism, on Canada’s contribution to the security of global supply chains, and on approaches to industrial policies.

The authors thank Charles DeLand, Stuart Bergman, Robert Dimitrieff, Kent Fellows, Gary Hufbauer, Brian Livingston and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier draft. The authors retain responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

Introduction and Global Scene-Setting

A supply chain is a series of geographically dispersed facilities, each performing tasks that contribute to making and delivering a product. From the 1960s onward, innovations such as the multi-modal container, wide-bodied jets, communications technology advances, and the rise of computing power – boosted by policies that liberalized international and domestic trade and investment – increased businesses’ ability to combine inputs from such geographically dispersed locations around the globe, and to deliver finished products to far-away customers (Van Assche 2012). This led to a sharp rise in cross-border trade and investment, and to a rise in the number and complexity of international agreements governing them. Together, these trends have underpinned the phenomenon known as “globalization.”

The international fragmentation of production along a supply chain enables each of its elements to contribute according to the location’s comparative advantages, keeping prices low for purchasers. For national economies, the emergence of global supply chains, and participation in them, enables the use of cost-efficient or more technologically advanced inputs (see Baldwin and Yan 2014 for a discussion centered on Canada), and the parlaying through trade of a country’s comparative advantages into higher productivity and standards of living. When there are multiple possible sources for components, flexibility is also an advantage, increasing resiliency in the event of disruptions in one part of the chain.

Thus, the ability of supply chains to operate efficiently should be a major policy objective of governments that aim to foster high incomes and affordable goods – in other words, raise standards of living.

Supply chains also embed risks, to the extent that their functioning depends on factors outside the jurisdiction or control of the businesses, individuals, or governments who operate or depend on them. These risks can be human made (e.g., strikes or blockades), natural (e.g., flooding), or a mixture of both (e.g., pandemics and how authorities react to them).1 They include cybercrime, sabotage, or wars, which can affect the ability of elements of the chains to perform their role reliably and efficiently, or to function at all. De-risking supply chains, or making them more resilient, is therefore a second major policy objective regarding supply chains.

By their globalized nature, supply chains invite questions about the role that different suppliers, however efficient and reliable, play in the achievement of broader policy goals, such as fostering human rights or a clean environment, or ensuring global, regional or national security. Further questions are prompted by their interplay with ancillary economic goals such as encouraging innovation and the growth of small businesses. Supporting the configuration of supply chains to optimize their ability to meet these goals is a third major goal of supply chain policy.

As we will see, there are tradeoffs between these objectives, but also complementarities to be exploited. For example, infrastructure that supports efficient movement of goods can also be built to be safe from cyberattacks, and to minimize emissions. In this paper, we will examine ways that a national supply chain strategy for Canada can help navigate these tradeoffs and foster complementarity between these objectives, and we propose policy actions toward achieving these goals. These policy actions fall into five buckets: 1) boost the competitiveness of Canada’s physical and regulatory infrastructure and encourage technology and skills adoption; 2) boost manufacturing preparedness and stockpiles for emergencies, but otherwise take a critical look at whether local production is necessarily a good defense against supply chain disruption; 3) reinforce trade alliances and economic diplomacy with trusted partners, and build our leverage in these alliances by focusing on Canada’s contribution to key supply chains; 4) make Canada an essential partner for security; 5) introduce a new framework to better evaluate public support for large industrial investments – including their impact on small businesses – which could better align them with Canada’s (or a region’s) comparative advantage within global supply chains and with sound economic development principles.

Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, which the World Health Organization declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern at the end of January 2020, brought home the importance of supply chains to Canadians’ daily lives. Measures taken to counter the health emergency paralyzed large swaths of production, transportation and sales, while simultaneously leading to a sharp rise in the need for medical and other goods necessary to deal with the crisis. From the mostly below-the-radar benefits that supply chains brought to consumers and businesses in the form of plentiful and affordable goods, public attention shifted to their resilience – meaning, in this context, “the capacity [or lack thereof] of industries and associated communities to anticipate, prepare, absorb, recover, and learn from supply chain disruptions” (New Zealand Productivity Commission 2024).

The pandemic-related shutdowns of many parts of key global, North American, Canadian, and even local supply chains meant that Canadians experienced for a time acute shortages of not only staple hygiene or food products, but also of medical products (and services dependent on the availability of these products) on which their very health or even lives depended. Authorities scrambled to procure these by any means. Indeed, many jurisdictions at some point or other pulled supplies their way at the expense of trade partners. They did this by blocking exports when they could exercise a lock on some critical medical goods that were in short supply or, conversely, overstocking on such goods when they became available on world markets.

The pandemic illustrated the fact that even if a far-away part of a supply chain becomes unexpectedly unreliable, or simply unavailable, and substitutes cannot be easily found, crippling shortages of goods on the domestic market can quickly result. There are only a few ways policymakers can avoid a repeat of such shortages in the future. Two of these are centered on domestic policy. First, maintaining stocks of essential goods2 is sometimes sensible when they have a reasonably long shelf life – such as personal protective equipment or vaccines – and storage is an option. Second, in theory, ensuring that these goods can be produced domestically is another option. Urgent need led to successes in shifting existing manufacturing capacity toward manufacturing personal protective equipment, ventilators, hand sanitizer, medical testing equipment, etc., here in Canada when sufficient international supplies were in doubt, on short notice. In this respect, the crisis highlighted the crucial role of dozens of Canadian manufacturers, including many small businesses, which were able to quickly and often ingeniously retool – or in some cases reopen – at the behest or with the support of government, to provide the necessary goods.

But such efforts would not be sustainable or scalable to a broad range of products without excessive costs to the broader economy. This is because they would require giving up the benefits of specialization, including forgoing the potential for higher incomes from Canadian production that would have been exported but is diverted to such a domestic production scheme. In addition, we cannot entirely anticipate what kind of threat we will face. As we note below, it would be practically impossible to ensure the domestic production of vaccines that could fully protect Canadians from the effects of a range of possible pandemics.

Therefore, while the first policy lesson from the pandemic relates to our ability to maintain inventories of certain essential goods, or to boost our own supplies of such goods in an emergency, the second lesson is the importance for the well-being of Canadians of keeping open global (and domestic) supply chains for essential goods and related services, as far as possible, when confronted with an emergency. Indeed, governments’ major (and by and large successful) efforts to bring supply chains back on track, notwithstanding a range of health-related restrictions on economic activity, showed how much they understood the benefits of well-functioning supply chains for the population at large.

On that score, the main diplomatic challenge during the pandemic was to ensure a continued flow of supplies between trade partners, each concerned with their own security of supply. For Canada, as a relatively small economy, two approaches seemed vital to secure such an outcome. The first was to lean on our supply of crucial components that our bigger trade partners needed to produce essential goods or services – giving us leverage to ensure that a share of the output produced by those partners would continue to flow to Canada. The story of Canada’s ability to leverage Canadian input into US medical supplies and services in a time of emergency – including nurses from Windsor, Ontario, working in Detroit hospitals during the pandemic – to convince the US Administration to reverse its proposed ban on exports of N95 masks, has entered folklore (see discussion in Gereffi 2020). The second approach was to agree, when it could, with like-minded partners, that trade should remain open among them for their common benefit in dealing with such a situation, as it did in 2020 under the aegis of the Ministerial Coordination Group on COVID-19.

We will examine below ways that Canada can foster – and contribute to – such cooperation to maintain the flow of essential goods and related services, such as transportation. This requires examining what contribution Canada can reliably make to the national security and safety of its partners, beyond commitments in trade agreements; i.e., how we can contribute to, and benefit from, formal partnerships that are wider and deeper than those provided simply by trade agreements. Although trade agreements provide a supportive framework and new opportunities to develop and sustain the business partnerships so crucial to keeping open the flow of goods, linkage with other issues is necessary to maintain essential trade flows in times of crisis, precisely because trade agreements contain exceptions for cases involving national security and public safety.

A third policy lesson from the pandemic concerns the interaction of governments and business, including small businesses. It is a fact that policy interventions helped, in that time of crisis, to prioritize and facilitate the production of essential goods, for example through public procurement and assistance for retooling and/or reopening safely. It is also the case that not only large firms but also smaller ones across Canada, and notably manufacturers, contributed significantly to that pivot,3 highlighting the importance of small businesses in shaping supply chain resilience (on the latter see Mills et al. 2022). At the same time, in a number of cases, governments’ response to the pandemic involved removing barriers to output, transportation and other services (such as health services) that may not have been obviously critical in ordinary times, but which suddenly emerged as important obstacles to the provision of essential goods and services to the public. Examples abound, ranging from regulatory forbearance allowing farmers to sell more directly to consumers, allowing digital transactions where in-person transactions were required, or helping freight move even in the face of the broader health-related lockdowns, as well as cooperation between different levels of government. The question, to which we will return below, is whether these examples can inform Canada’s supply chain policy going forward.

Post-Pandemic Stresses, De-risking and Avoiding Choke Points

Factories and a modicum of international transportation services were able to reopen safely and progressively after the initial pandemic shock, in step with effective measures implemented in these sectors by governments and industry. With governments in Western economies having implemented job and income support programs while in-person contacts were still discouraged, e-commerce rose phenomenally, enabling supply chains to extend to the “last mile” directly to consumers’ homes. Consumers, unable to travel, or to go to public places for enjoyment or exercise, suddenly became avid buyers of products for the home – a shift that caused equally sudden shortages of such products, given producers had not planned for, or otherwise couldn’t meet, such a rise (for a discussion of the shift in consumer demand from services to goods during that period, see Global Affairs Canada 2024, section 2.2).

With some countries experiencing continued bouts of the virus, supply chains and transportation routes slow to get back to normal,4 and pent-up consumer demand now unleashed in countries reopening more fully, the ability of supply chains to deliver products in demand was strained. Recent studies show that abnormal demand patterns were the cause of the pick-up in pandemic-era inflation, and not supply-chain breakdowns (Levy 2024).

The great ports bottlenecks of late 2021 to mid-2022, which affected both imports and exports, possibly mark the crescendo of pandemic-induced supply chain stresses (see, for example, Frittelli and Wong 2021).

Bottlenecks may occur at a particular geographical location through which trade must transit, or at a plant or firm whose operation is essential to the continued functioning of a supply chain, or even arise as a result of a monopoly position that a country has built in a specific type of product necessary to a supply chain. All of these can become choke points when they are exploited for economic or political purposes, and may be vulnerable to various threats or accidents, highlighted by phenomena such as the blocking of the Suez Canal when a container ship ran aground there in March 2021,5 or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and its immediate aftermath, which threatened global grain supplies and European energy supplies.

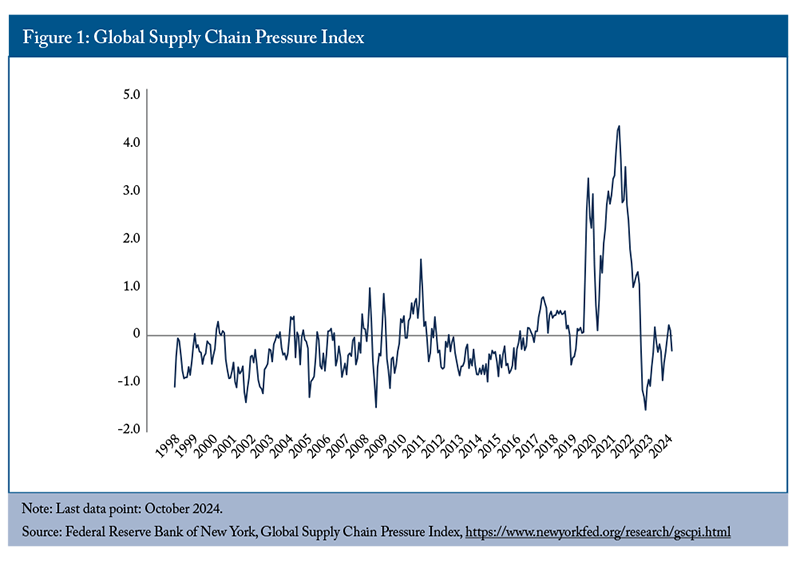

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, which tracks several indices related to backlogs and transport costs, shows that – after easing sharply from the surge in demand for goods that had created the “great ports bottleneck,” and the initial shock caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2023 – they were, at the time of writing, back up almost to their average value during the 16 years tracked by the index (Figure 1). This average is skewed, however, by the enormous pressure sustained by supply chains in the pandemic; at the time of writing, the pressure was in fact higher than in most of the period for which the data have been compiled.

Environmental phenomena have also exposed the vulnerability to bottlenecks – this is in addition to the impact of climate change on the source, and overall availability of, agricultural supplies (coffee, bees for pollination, etc.). Examples include the first-ever limits, imposed this year, on shipping through the Panama Canal due to low water levels (partially reversed as of the time of writing), and the wildfires and then floods that prevented traffic in and out of the Port of Vancouver for many weeks in the summer and fall of 2021. While there is not much that an individual country can do to prevent these, each country needs to prepare for them, including by anticipating the need for alternative sources of supplies, or trade routes when existing ones are blocked.

The risk of coercive or even possibly violent actions by powerful countries, such as China, with whom a normal trade relationship, based on mutual economic interests and accepted rules, might once have been contemplated, has come to the fore. The threat may not be in the form of military action, but rather in the form of actions to exploit the choke points they control in areas such as food, energy, or “dual-use” electronics and other sensitive technologies that are vital to both economic growth and national security.

The response of Western governments to these choke point risks has been a mixture of 1) “decoupling” from an existing or prospective hostile power – through sanctions, export controls, banning of certain of their products from the domestic market, limiting inward or outward exchanges of knowledge (e.g., technical or academic exchanges) – and 2) of “de-risking,” where an all-out ban of trade makes little economic sense. Both the United States and the EU have officially sought de-risking rather than de-coupling from China, focusing both on limiting China’s acquisition of dual-use technologies by which it could benefit strategically, and on boosting productive capacity in strategic industries at home or in friendly countries to reduce reliance on China or on economies potentially vulnerable to Chinese coercion.

This de-risking strategy has extended to technologies considered critical to future growth, among them microchips (e.g., the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, see Luo and Van Assche 2023) and green technologies such as those for electric vehicles (the US Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 with its emphasis on “green” purchases sourced in the United States, or in some cases close US trade partners), and to the materials considered, in turn, to be critical inputs for these and military technologies. There has been increasing international cooperation among Western economies on that front (e.g., the Canada-US Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration, the Canada-EU Strategic Partnership on Raw Materials, and similar agreements), as part of a broad trend of “friend-shoring” production of imports vital to domestic economies.

But de-risking has a cost: it inherently involves preventing some low-cost foreign supplies from accessing domestic markets in the name of supply security, namely, of ensuring the availability of supplies and production capacity not subject to control by potentially hostile forces. De-risking represents a suite of “defensive” measures implemented against actual or potential “offensive” measures taken by others that could leave one’s economy vulnerable to hostile forces (Van Assche 2024). It can entail shoring up domestic producers via import duties, border adjustments, minimum prices for domestic production, or subsidies, against production from problematic sources. They are problematic because they are potentially hostile or coercive, seek to control critical sources of supply, lavishly subsidize their own export-oriented industry to gain market share, or otherwise do not meet product or production standards (environmental, human rights, etc.) that would be the norm domestically.6 All these measures have costs: they entail navigating a tradeoff between national security objectives which often now encompass a nation’s perceived economic security,7on the one hand, and the higher cost or lesser availability of otherwise desirable goods, on the other. It is a tradeoff between the efficiency of supply chains able to bring plentiful goods to consumers and businesses at low monetary cost, and other desirable public policy objectives.

Balancing Efficiency and Economic Security: Avoiding the Pitfalls of Industrial Policy

Readers familiar with discussions on the effectiveness and pitfalls of “industrial policy” will recognize that the measures listed in the middle of the previous paragraph (of which a useful recent compendium can be found in Ilyina et al. 2024) are part of the toolkit of such a policy.

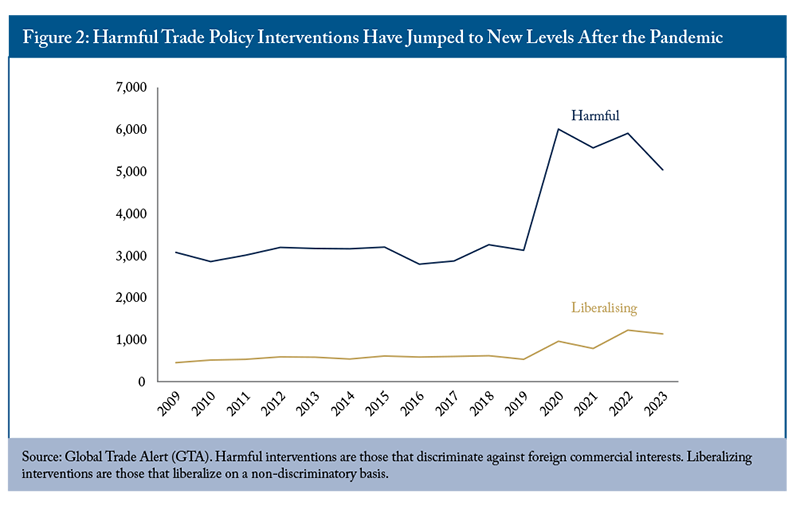

The Peterson Institute for International Economics defines industrial policy as “government intervention in domestic industry against market forces through subsidies, tax and trade policies, and more to foster certain sectors or companies or protect them from foreign competition.” Such policies have been gaining currency around the world, especially since the pandemic. According to data from the Global Trade Alert, harmful trade policy interventions – those that distort trade by disadvantaging foreign companies in local markets (e.g., tariffs, subsidies) – have jumped from around 3,000 per year before the pandemic to over 5,000 per year after the pandemic. Meanwhile, the number of trade policy interventions aimed at liberalizing trade or improving the competitiveness of foreign firms has remained largely stable.

A major driver of this trend has been the reversal in American trade policy, turning inwards and away from supporting the rules-based trade order. In his first term (2017-2021), President Trump rejected former trade-opening trade agreements as having been unfair to the United States. He rejected the Trans-Pacific Partnership which had been negotiated by his predecessor,8 he insisted on impossible-to-achieve (at least via tariffs) trade balancing between countries, and his administration imposed steep tariffs on certain industrial and consumer goods imports. The NAFTA renegotiations he initiated, which led to that agreement being replaced by the Canada United States Mexico Agreement (CUSMA, as it is known in Canada) in 2020, were explicitly aimed at shifting key elements of certain supply chains, notably automotive, from lower-wage jurisdictions back to the United States – with little apparent regard to the cost to US consumers or to overall US competitiveness. Superimpose on these trends the policy interventions that President Biden has implemented to address security concerns, including economic security, and promote a clean energy transition, and we have a rapidly expanding hodge-podge of industrial policies (see Manak 2024). These often entail creating or sustaining domestic, or at least friendly, sources of supply in those industries or technologies deemed critical to growth and security.

Thus, the general aim of the mutual or even unilateral opening of borders has taken the back seat in many countries to “re-shoring,” or at best “near-shoring” with those lower-cost jurisdictions more amenable to bring reciprocal gains (such as Mexico to the United States). Another option is “friend-shoring” with economies sharing compatible policy objectives that could be mutually advanced by closer economic links. An example: Western economies fostering trade ties with countries such as Vietnam, whose production may to some extent substitute for China’s.9 These shifts engineered by governments have contributed to a “slowbalization” of the world economy, illustrated by the fact that the relationship between global merchandise trade growth and GDP growth is now back to where it was 50 years ago. To the extent this reduction in the “elasticity” of global merchandise trade to GDP represents a lessening of specialization that had resulted in the rise of incomes under globalization, it is also slowing down overall economic growth (Mattoo 2024).

These strategies and restrictions on trade and investment flows risk being very costly to both the economies undertaking them and their trade partners (Ciuriak 2023).10 In general, industrial policies, including trade-related policies such as US trade restrictions on Japanese autos in the 1980s, have a mixed record of success (Hufbauer and Jung 2021). In turn, it is not clear how this time will be different unless some discipline or principles can be brought to the interventions to ensure a greater chance of success than in the past.

Although it may seem like a stretch, given geopolitical tensions, it is important for international groupings such as the G20 to build on the work of the G711 foster some discipline – or even just common understanding – among governments regarding how “economic security” is used to justify barriers to trade.

Global Supply Chains: Reconfiguring, But Not Breaking

Even in the United States, attempts to implement President Trump’s first-term, high-tariff agenda – invoking spurious national security reasons against Canada and other friendly nations to impose punitive tariffs on steel and aluminum, for example – ran against the fact that domestic customers and consumers were suddenly exposed to higher costs and the sudden unavailability of imported supplies. A similar dynamic appeared in the UK after the institution of Brexit, when consumers and businesses discovered the sometimes-high costs that their choice entailed. Even in the face of security threats from China, foreign policy experts reckon that “the economies of the United States and China are inextricably entangled, however much economic nationalists in both countries resent that fact. There is no plausible way to completely unwind this interdependence or detach the civilian and military economies from each other without causing irreparable harm to American society” (Farrell and Newman 2023).

These and other examples show the limits to “deglobalization,” and more specifically the difficulties of a decoupling agenda that seeks to make one country an economic or technological leader by restricting imports, risking instead reduced affordability and lower innovation through reduced competition.

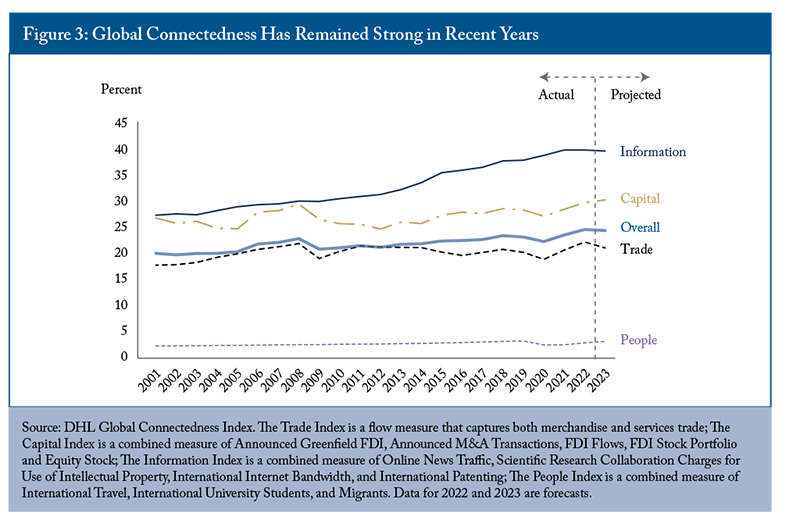

Perhaps for these reasons, and despite the drop in the ratio of trade to GDP, broader measures of globalization, which include investment, financial, and regulatory harmonization variables, seem more at a standstill than fully in retreat. The KOF Swiss Economic Institute has tracked both “de jure” globalization – agreements to open and to harmonize rules – and “de facto” globalization – the actual level of cross-border trade,12 investments and other financial flows. Like the IMF, it notes a “slowbalization” of both trade and other economic flows, and of trade rules since the early 2000’s, noted above, but no catastrophic decline (see Jenkins and Kruger). Indeed, it records a continuing (if slowing) upward trend in “de jure” globalization harmonization, which KOF empirically associates with firms able to capture the benefits of trade, perhaps due to the effects of harmonized rules on the “contestability” of markets. As is shown in Figure 3, Altman et al. (2024) similarly find strong resilience of international flows across the globe. Trade, capital and information flows all rose to, or approached, record high levels in 2022 and 2023. Only the people pillar remained below its 2019 peak level due to the slow post-COVID recovery of international travel. Finally, indicators of trade in value added – which show how much foreign value added (including services) is embedded in a country’s own exports and thus is one indicator of integration in global supply chains – support the notion that there has been “slowbalization,” but not deglobalization, since the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis (Knutsson et al. 2023).

The direction of trade flows is changing for certain. This is most notable in the case of China and the United States, where the US, particularly since the beginning of the Trump administration (but continued under its successor and, prospectively, Trump’s return to office), has emphasized tariffs and other policies straightforwardly aimed at reducing Chinese imports and Chinese competitiveness in advanced technology. Despite all the turmoil – pandemic, tariffs, security issues, etc. – centered on China, the evidence points to a “great reallocation” of trade, with US imports rising instead from countries such as India, Vietnam and Mexico (which has now overtaken China as the #1 importer of goods in the United States), rather than reshoring to the United States (Alfaro and Chor 2023). The shift of trade to these countries has occurred for both strategic (more congenial relationship with the United States) and cost (relative rise in Chinese wages) reasons. Indeed, these countries in turn are recipients of growing Chinese investments, to the extent that it is not clear that the United States is really diminishing its reliance on China (Freund et al. 2023).

In contrast to findings for the United States, Van Assche and Zhou (2024) note that imports from China have continued to increase as a share of total Canadian imports. The recent imposition by Canada of extraordinary tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, steel and aluminum, bringing Canada in line with the US on that score, may well change that picture. Van Assche and Zhou note, however, that Canadian imports from CPTPP countries, and for that matter Canadian imports from the EU under the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, have outpaced imports from the United States since these agreements have been in place. This illustrates how Canadian importers can adapt to any “great reallocation” away from China – not through near-shoring, but friend-shoring. Indeed, as with the United States, there is little evidence of reshoring of economic activity in Canada as a result of the pandemic-related turmoil and subsequent greater scrutiny of supply chains (Blais-Morisset and Rao 2024).

Implications for Supply Chain Policy

The rise of trade barriers and domestic industrial policies do not seem to have diminished the appetite for more fluid supply chains, and for trade facilitation in general.13 This seems contradictory only on the surface: while governments seek to be more directive of certain trade (and investment) flows – namely, to leave them less to market forces and interpretation by dispute settlement bodies – they do want those trade flows they do not disapprove of – including their own country’s exports – to move as efficiently and securely as possible. Indeed, supply chain policies, including those that facilitate external trade, are all the rage, ranging from Australia’s National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy established in 2019, to the multi-Departmental Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force created by the US Administration in 2021 (which met most recently to address supply chain disruptions caused by the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore), the National Logistics Policy of India unveiled in 2022, and many others. Canada has been a laggard in that respect.

While individual firms of all sizes, both in Canada and globally, continue to regularly report experiencing supply chain problems exceeding pre-pandemic normal, and continue to worry about them far more than before the pandemic, surveys suggest that businesses expect that these will fall over time. That perspective makes sense from a firm level, as firms will adjust for what they can control, and may expect governments to do their part to ensure efficient and resilient supply chains that will benefit businesses and consumers. Canadian governments, however, need to actively monitor supply chains for vulnerabilities that could disrupt vital parts of Canada’s economy, and take measures to address or alleviate these risks, or at least ensure Canadians are prepared for them.

Authorities are now more likely to look “under the hood” of supply chains, for the security and policy reasons mentioned above, and to make big firms liable for human rights and environmental violations that occur in their global supply chains. Tougher restrictions on imports that use slave or enforced labour, and the need for more transparent origin in general, whether at consumers’ behest or demanded by rules of origin under trade agreements, along with national security and environmental considerations, all require enhanced traceability throughout supply chains. “Know your supplier” has become a standard business requirement, along with “Know your customer.” While supply chain transparency may be difficult and costly to achieve, and may put those corporations subject to public disclosure requirements at a disadvantage relative to those who are not, it is increasingly the price to pay to facilitate international trade.

Canadian governments should encourage the adoption of technologies that ensure traceability and security (e.g., against malicious use of digital technologies) throughout the supply chain in ways that can keep the costs of doing so low. In that vein, governments should foster more efficient and resilient logistics through AI and the participation of more small and medium-sized businesses as trusted suppliers in larger supply chains.

The upshot is that supply chain policies are now intertwined not only with trade, but with security, climate, human rights, business growth and technology policies, in the avowed service of affordability and higher standards of living. Supply chain issues therefore continue, in one form or another, to be near the top of the economic agenda for firms and policymakers alike. In both policy and management circles, adopting a supply chain mindset has become critical.

A Canadian National Supply Chain Strategy: Reducing Vulnerabilities, Capturing Opportunities

Canada has yet to unveil its long-promised National Supply Chain Strategy. It has, however, launched a new National Supply Chain Office in December 2023, nested within Transport Canada. The new Office is responsible for the development of the strategy, in addition to its practical roles in helping the federal government respond to major supply chain disruptions, encouraging data-sharing, and “help[ing] government and industry make smarter policy, regulatory, investment and operational decisions.”

This new Office was one of the recommendations of Canada’s Supply Chain Task Force, which reported to the Minister of Transport in late 2022.

We believe, however, that the development of an adequate supply chain strategy for the country exceeds the mandate of Transport Canada, given the ramifications of supply chains just outlined, and the level of capital to be invested.

In that light, we propose three strategic goals for a Canadian supply chain policy:

1) Maintain the economy’s ability to supply essential goods and services – notably food, medical and health, energy, and other essential supplies – to Canadians and Canadian industry in the face of plausible geopolitical, climate-related, health-related or other disruptions. The Canadian federal government and the provinces should maintain an agreed-upon common list of essential goods and services, stress-test the economy’s ability to provide them in the face of such plausible disruptions, and pro-actively engage with industry – including foreign-owned companies and the small businesses that are routinely described as “the backbone” of Canada’s economy – to maintain the ability to provide these goods to Canadians, including through stockpiling where sensible.

2) Ensure that, in the ordinary course of business, both our exports (including between Canadian jurisdictions) and imports, on which so much of Canadians’ living standards depend, can move competitively and safely to markets. This includes ensuring the existence of cost-competitive, resilient and safe and secure infrastructure and transportation services, and finding ways to “de-risk” Canadian trade against trade partners’ policies that might impede normal Canadian production and trade. To that effect, maintain a comprehensive list of suppliers of critical materials including those our key partners consider critical. Note key risks to the availability of these materials in Canada and explain the government’s framework for reducing and responding to these risks should they materialize, including aligning our strategy with those of friendly trade partners.

3) Ensure that firms located in Canada play a role consistent with Canada’s comparative advantage14 within the supply chains that support emerging global and Canadian public needs and objectives, while strengthening Canada’s relevance in global value chains. Prominent among these is the need for goods, technologies and services that can help counter growing security threats, including threats to food and energy security, or to supply chains themselves. Also prominent is the need for goods, services and technologies that can support mitigation and adaptation to climate change globally and at home.

We propose that actions towards achieving these strategic goals be grouped under five main policy elements. These are based on the review of supply chain policies in comparator economies (see notably Australia 2019, Australia 2023 and New Zealand 2024), as well as on the work of Canada’s own 2022 Supply Chain Task Force. They are also based on an examination of Canada’s vulnerabilities with respect to domestic and international supply chains, and on some sound policy principles which, as we explain below, should help avoid costly pitfalls in implementing the strategy. Finally, we note that some of the challenges facing supply chains globally today represent opportunities that Canada could exploit as part of a comprehensive supply chain strategy. Taken together, the five elements below should therefore be seen as both addressing vulnerabilities and seizing opportunities.

Our first element concerns Canada’s ability to move goods and people:

1) Building competitive, resilient, and safe infrastructure and foster a cooperative regulatory approach to infrastructure and transportation.

This element of the strategy is essential to Canada’s ability to deliver on and benefit from the other elements, and from Canada’s strengths more generally – furthermore, it is an element entirely in our power. Yet Canada’s infrastructure investments have fallen behind those in other G7 countries and Australia on several metrics, affecting the country’s competitiveness (Khanal, Mansell and Fellows 2023). In addition, a comparison of frameworks for the delivery of large infrastructure projects in five jurisdictions, published in 2021, found that Canada was behind the EU, Australia, Switzerland, and the United States in having a well-defined transport infrastructure strategy (European Court of Auditors 2021). It bears repeating that Canada and the provinces can do more, and in a more cooperative manner, to make the process of reviewing and approving large investment projects speedier and more effective, an area where we also lag (Bishop 2019, DeLand and Gilmour 2024).

In contrast, Australia launched a comprehensive National Action Plan in August 2019 (Australia 2019) as an outcome of its National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy, in turn orchestrated by its Transport and Infrastructure Council, comprising state and federal governments. Canada was somewhat late to this type of initiative, with its Council of Ministers Responsible for Transportation and Highway Safety launching a Pan-Canadian Competitive Trade Corridor Initiative in 2020. In the midst of the extreme supply chain bottlenecks discussed above, the federal government also commissioned in March 2022 the aforementioned Supply Chain Task Force to give independent advice to the federal Minister of Transport on transportation issues affecting supply chains. The report of the Task Force did note that considerable investments must be made in Canada’s supply chain ($4.4 trillion), but did not make any specific recommendation as to how such a large investment (admittedly both by the public and private sectors) should be structured.

In addition, recent events such as repeated work stoppages in strategic Canadian ports (Vancouver, Prince Rupert and Montreal), or the impasse in labour negotiations between rail workers and Canada’s two major railways (centered on the need for updated work arrangements that can support the competitiveness of Canada’s railway system while maintaining high safety standards, beyond federal safety regulations) highlight the need for an innovative labour and regulatory agenda. This agenda might support workers’ incomes through necessary changes and enhance their and the public’s safety while ensuring that disagreements do not take the public hostage via major supply chain disruptions at Canada’s infrastructure choke points.

There also remain gaps in the availability of skilled workers (or in the recognition of their credentials) able to operate effectively and safely in areas crucial to the smooth functioning of supply chains, such as trucking. But these gaps vary with the vagaries of demand, and require industry-specific strategies involving technology, skills building and transferability, and regulatory solutions.

Many recommendations of the Supply Chain Task Force, with respect to strengthening Canada’s Transport infrastructure, align well with addressing Canada’s logistics vulnerabilities where they concern actual international trade flows (described in Jian and Scarffe 2021).

But with respect to labour, some recommendations seem incomplete and even counterproductive. The Task Force recommended not only training (good) but also continued reliance on temporary foreign workers for the foreseeable future, warning the government against restricting that program. It could have considered the longer term and asked how changes in truck technologies, port mechanization, digitalization and other innovations might have transformed future workforce requirements, in addition to capital spending requirements. Indeed, Australia’s strategy, in striking contrast, details the role of data and digital infrastructure in ensuring better functioning supply chains. In fairness, these issues are also discussed under Canada’s Competitive Trade Corridor Initiative, but without concrete improvements proposed.

The Task Force said the right things about unnecessarily burdensome or inflexible regulation, and especially about extra capacity to relieve bottlenecks at international borders. But it could have also recommended Canadian federal and provincial transport ministers implement the excellent list of suggested approaches to support efficient movement of trucks across Canada, contained in the 2018 report of the Task force on Regulatory Harmonization which they convened. Further, it could have suggested a list of remaining issues to be addressed by the Regulatory Reconciliation and Cooperation table set up under the 2017 Canadian Free Trade Agreement. In general, removing barriers to internal trade is particularly significant for fostering the growth of small businesses, whose first or best initial out-of-province sales opportunities are often in the Canadian market.

We also think that the National Supply Chains Task Force could have done a better job attempting to solve the thorny issue of interswitching in favour of grain producers, and of the disruptive issues of strikes or blockades. Our view is that these questions, vital for Canada given its vulnerable geography, need to be addressed with greater transportation capacity around potential choke points, not less. The Task Force’s proposal on interswitching risks, rather, discouraging investment in Canadian rail.

Recent meaningful steps to improve Canada’s Transport Infrastructure included substantial federal investments ($4.6 billion to date) through the National Trade Corridors Fund, which must be spent on trade-enabling projects completed within five years. The two-step process for allocating funds based on merit is commendable and, given Canada’s shortfall, should be expanded. In turn, these have helped specific nodes in Canada’s transport supply chains, such as the Port of Vancouver, implement new programs to improve their supply chain performance. However, the productivity of Canada’s major ports, like that of their North American counterparts, lags far behind other major competing ports more willing to embrace technology and innovative labour practices.

Considering the capital investments required in Canada’s transportation supply chain, public funding, such as the National Trade Corridors Fund, is certainly welcome. But private capital is also required to close the gap with other industrialized countries. Measures which will encourage (or at least not discourage) these investments should be implemented rapidly.

Overall, Australia’s approach is more integrated across governments, including at the local level, and both more consultative and ambitious on many fronts. It is a “whole of government” approach, of the kind we now propose here for Canada. Its Action Plan includes not only a detailed list of specific barriers, but a specific timeline for addressing them, and feedback mechanisms to address issues in implementation as they arise. Indeed, Australia is in the middle of a five-year review of this plan (Australia 2023). There is a lot here for Canada to think about – and catch up to.

Canada’s national and provincial plans should draw from the lessons of the pandemic, reviewed above, regarding regulation, government procurement, and the importance of small and medium-sized businesses for supply chain resiliency.15 Promising avenues regarding the latter include focused public procurement strategies aimed at firms that build the capacity to react to supply chain crises, contribute to the security and safety of supply chains, and strive to meet the high standards required for participation in supply chains – not just in Canada but globally, and governments setting up a financing facility to support production in SME’s at times of crisis.

One way to galvanize institutions, businesses and labour around such a supply chain agenda would be to imagine how Canadian supply chains would react in the event of an emergency or sudden change – another pandemic, a cyber-attack on our transport infrastructure, major new barriers to Canadian foreign trade, or disruptions at choke points along key supply chains – and what the impact on the public would be. Such “stress tests,” evoked earlier, would inform a continued examination of Canada’s infrastructure, trade and industrial, and regulatory agendas. This would be with a view to identifying improvements needed to promote affordability, security, and the good jobs that stem from a productive economy – all of which depend on efficient and resilient supply chains.

Canada could incent the provinces to cooperate on such improvements through funding arrangements meant to share in expected productivity gains, as was done in Australia for the removal of internal trade barriers.

2) Do not assume domestic production is a sufficient – or even necessarily good – defence against supply chain disruptions.

The shortage of essential goods experienced during the pandemic might well have happened even if Canada’s entire consumption of such products, down to the last component, was made in Canada. In general, localized production does not mean certainty of supplies, and indeed it may simply mean more vulnerability to local events. In the face of sudden shifts in demand, local output may be just as constrained in the short run as global output for a particular good. To use an extreme example, famines are notoriously worse in places where imports cannot temporarily replace local production.

While relying on local production may give decision-makers the illusion of control, unanticipated spikes in demand such as the ones that occurred in the pandemic’s aftermath are only successfully handled with local supplies if these are by chance available, or if governments are somehow able to maintain sufficient inventories or surplus capacity in those goods that might be in shortage. Governments and firms will certainly want to be better prepared for the next crisis through a more deliberate policy of maintaining both stockpiles of critical goods and surge capacity to deliver critical services.16 But having production facilities at the ready for any eventuality is an almost impossible proposition, at least for a mid-sized economy like Canada’s. Grootendorst et al. (2022) demonstrates this point for vaccines – there are just too many possible diseases against which we may wish to protect ourselves, notwithstanding the new Moderna facilities in Laval, Québec, which will be able to produce certain mRNA vaccines for respiratory illnesses such as COVID.

Diversity of potential sources of supply is a strength, not a weakness, and indeed localization may not be embraced by consumers or investors, as the failure of Quebec’s “panier bleu” initiative – a COVID time program to encourage the online purchase of Québec-based goods – suggests. This leads us to our third major element of a National Supply Chain Strategy:

3) Reinforce trade alliances and economic diplomacy with trusted partners.

Unlike the United States, the European Union, or China, Canada cannot even remotely think in terms of self-reliant domestic manufacturing. Even in larger economies, the secret to surviving major disruptions reasonably well is a smart management of international interdependence. This is in spite of the security-motivated, and sometimes necessary, urge to boost local content for goods in suddenly short supply, or to prevent domestic supplies of essential goods from being exported.

To be sure, there are vulnerabilities inherent in the reliance on international trade. At a macro-economic level, Statistics Canada reports that “Canadian industries accounting for 25% of the country’s economic output are exposed to potential external demand and supply shocks. Rising import prices accounted for about half of consumer inflation at its peak in the last three quarters of 2022.” However, these are fairly mechanical considerations related to exposure to external trade – reliance on entirely domestic supply chain can sometimes be just as fraught, for example in the event of a plant or significant transport disruption.

Vulnerability to international shocks can also be a function of the lack of diversification in the geographical origin of imports; the greater the number of countries supplying a product, the less vulnerable an importing industry is to supply shocks (Boileau and Sydor 2020). Jiang (2021) identifies more precisely 104 out of some 5,000 products imported into Canada that are vulnerable to disruptions from the country in which they originate, in the sense of not having obvious alternative suppliers either inside or outside Canada. China was the largest overseas supplier of such quasi “unique” imports, followed by India, Germany, Italy and Switzerland.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Scarffe (2022) notes that Canada specializes as an upstream (materials) exporter to global supply chains, and as an importer closer to the downstream (final goods). This makes it more vulnerable to global supply disruptions at that end of supply chains. Significantly, the only country to which Canadian exports showed a significant movement “up” the supply chain since 2010 was China, presumably as this economy becomes a more sophisticated consumer of foreign goods.

Overall, this work shows the importance of Canada securing access to more diverse sources of supply for imports that are both vulnerable to disruptions from a single country, and are vital to the Canadian economy. Of note, New Zealand’s trade ministry maintained such a list of essential imports and sought reciprocal arrangements with like-minded partners such as Singapore to maintain as far as possible open trade in these products during the pandemic. The New Zealand-Singapore agreement lives on today and has been deepened as part of their strategic relationship, pledging to work together in the event of crisis, notably on food security. Canada should similarly engage at the strategic level with key existing and prospective partners, paying attention also to the ultimate source of inputs in products it must continue to be able to import, and make sure these can remain accessible. For example, while there may be a multitude of pharmaceutical products available on the global market, many depend on the same few active pharmaceutical ingredients.

As noted, imports from China have continued to rise as a share of total Canadian imports, contrary to the trend in US imports (but similar to the trend in EU imports from China). To the extent that the difference is due to fewer restrictions on Chinese imports into Canada than in the United States, Canada should be wary of the incoming second Trump Administration, which has made higher tariffs on imported goods, from China in particular, one of its key trade battle cries. It is likely to scrutinize and restrict imports more zealously from its neighbours to ensure they are not a platform for indirect imports from China. Indeed, as mentioned, Canada has recently imposed extraordinary tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, aligning itself with the United States in this case. It would be surprising if the question of a closer alignment of Canada and US trade measures toward problematic third parties did not come up in the CUSMA review due to take place in June 2026, at least implicitly as a way for Canada to preserve its access to the US market. The upshot is that Canadian importers may need to look even more to CPTPP or other Asia-Pacific countries as sources of imports.

Overall, the analysis shows the importance of Canada diversifying its Asian sources of supplies away from China in specific goods – hence the importance of the trade agreements being negotiated with ASEAN, and bilaterally with Indonesia. Further, this highlights the importance of executing Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, unveiled in 2022, which appropriately puts the supply chain discussion in the context of the broader relationships with countries in the region. That such broader relationships have an impact on trade and especially on the possibility of cooperation during a crisis, in light of the disruptions outlined earlier in the paper, seems to us obvious.

This broader approach is also the one Canada needs to take with the United States. Although fairly balanced in terms of volume of trade, the mutual reliance of the two economies on each other naturally leaves the smaller economy, Canada, more exposed to policy vagaries and other disruptions that may originate in the larger one. The risk of such disruptions happening have increased given the views of the incoming second Trump Administration. However, this mutual reliance is also one of Canada’s greatest sources of economic strength.

Ahead of the trilateral review of CUSMA that will formally take place in 2026, Canada should reach out to business leaders in key cross-border supply chains, to review both the mutual benefits and challenges. This would allow Canada to approach the United States with a strong agenda of mutually beneficial improvements and, where it makes sense, common approaches to threats to, or through, the supply chain (e.g., cybersecurity threats), reinforcing the view that trade with Canada is not a threat, but is mutually beneficial.

That said, Canada’s share of the world economy is shrinking. Observers note that Canada is often perceived as a bystander in international relations more generally – for example, not being invited to participate in budding alliances such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. We cannot assume that partners will automatically see the benefit of engaging with Canada, when they may see Canada as a declining or even unreliable partner.

In this context, to better capture the potential benefits of participation in global supply chains through trade, Canada needs to offer something more engaging to partners – whether a more open and dynamic economy, or a stronger contribution to resolving key global problems, notably those around security. This leads us to think of other tools Canada should use, and contributions it should make, to reinforce its role as a key partner in global supply chains.

4) Position Canada as an essential partner for security.

In line with geopolitical tensions, military spending is rising rapidly among many of Canada’s trade partners. This is in response to the physical threats or actual violence by state and non-state actors. Canada lags behind its NATO partners in military spending and in its military preparedness in general, owing to both underspending and byzantine procurement practices.

Canada’s lack of a supply chain strategy has real consequences for how we are able to fill these gaps. Neglect of our naval building supply chain for example, and especially the loss of skilled workers, is resulting in significant delays in the delivery of Canada’s recently revived military shipbuilding program. There is a broader lesson here: Canada’s supply chain strategy requires adopting a longer-term vision for whether and how we maintain skills in industries that are characterized by large, but ‘fits-and-starts’, orders.

Cyber-security threats (not merely espionage, but the potential for sabotage) have risen to alarming levels. Indeed, cyber-attacks and data breaches have risen to the top of supply chain resilience concerns of major organizations, and addressing them needs to be a main focus of supply chain policy. Canada’s existing cybersecurity strategy has an explicit supply chain component – both protecting against threats to, and stemming from, supply chains.

We propose that the defense and de-risking of global supply chains – and notably the protection of key global trade routes, including the Northwest passage – likewise become an explicit and vigorous part of Canada’s defense strategy.

From a more mercenary perspective, we note that in times of shortages, leverage counts with respect to obtaining some of the available supply. Leverage can be financial of course; Canada’s buying power enabled it to hoard supplies of COVID vaccines well in excess of its likely needs, at the expense of countries who could afford such vaccines less. But there are other forms of leverage that come with controlling key inputs into a product of importance to trade partners, as the story of N-95 masks recounted earlier demonstrates.17

Canada should conduct the mirror image of the vulnerability analysis mentioned above and ask: for which product, considered essential by our trade partners, does Canadian production constitute a critical part of the value chain? Highlighting this contribution would help inform the strategic engagement with partners on maintaining trade in essential goods in an emergency. This exercise could be conducted for all essential goods, and the development of new Canadian facilities could even be contemplated where Canada could truly occupy a competitive position in those supply chains.

5) Respond more selectively to pressures for “strategic” industrial interventions.

As noted, there is growing affection for industrial policies, including interventions by our trade partners – and competitors – toward boosting their domestic output and supply chains in “strategic” areas, such as green or dual-use technologies and products, and in the critical minerals that underpin this strategic output. The tendency of Canadian policymakers to follow suit is understandable, especially as we are not trying to pick “winning sectors” ourselves: in a broad sense the global “winners” – the strategic industries everyone apparently needs more of – have already been picked for us by our trade partners.

But we contend that industrial policymaking needs to be constrained by at least some notional cost-benefit analysis, if only because Canada does not have the luxury of costly failures that some larger, more diversified, and perhaps more dynamic economies have. When deciding how it will support participation in these supply chains, whether through large subsidies or the allocation of other resources such as publicly produced electricity, Canada should more explicitly delineate what actual comparative advantages it will seek to leverage or build, and why there are no alternatives than to commit these resources.

At the same time, it should be wary of uni-directional technological bets that it or its partners may make to address the goals of industrial policy, as well as of setting unrealistic goals for the policy. Canada should consider continuing to support research in, and development of, alternative or transition solutions to the problems that the industrial policy du jour seeks to address. For example, should Canada go all-in with electric vehicles, or will hybrid or brand-new fuel technologies emerge in which Canada can seek an advantage and profitably be a player? If nuclear can play a role in ensuring reliable power where currently wind and solar cannot, given the current state of energy storage technologies, what is the plan for ensuring that the required materials and skills are available to build and operate the necessary facilities? And the development of energy storage technologies could itself be a goal of a multi-directional supply chain strategy, which requires accepting that not all bets will pay off. The policy should be explicit on the point of technological bets, and their supply chain implications.

Other than as might be needed to position Canadian locations as indispensable links in essential global supply chains, as recommended above, supply chain policies should not: 1) tie Canada to a single technology unless it is clear that a single technology that Canada can develop or which it can use competitively will emerge to meet our or trading partners’ needs; 2) commit Canada to invest in, or subsidize, economic activities in which it (or the region the investment is located in) does not plausibly have a comparative advantage. This means, in particular, that a supply chain strategy should not automatically aim at building entire “verticals” or entirely domestic supply chains, unless Canada already has the resources, knowledge and skills that give it an advantage in each part of that chain, compared with its trade partners.

Beyond their costs to taxpayers, industrial policies based on attracting or making investments in a region that are not well-rooted in the region’s comparative advantages will not only have fewer chances of success, but they will also detract from what would be a sustainable growth path for smaller local businesses. They would do this by potentially increasing costs for small businesses to operate, rather than allowing them to benefit from opportunities created by the investment (Laurin 2023).

This approach also means, however, that if a trade partner subsidizes its export-oriented production activities in a way that threatens an otherwise competitive Canadian industry, or artificially depresses prices of products in which Canada does have a comparative advantage, with a view to driving Canadian or other competition out of the market, Canada should consider similarly supporting its industry, via subsidies, price support or tariffs, sufficient that the investment takes place where it would have happened without the trade partners’ distortions – in Canada.18

This overall approach would apply on a product by product, or task by task, basis. Take lithium mining, for example, identified as critical by Canada because it enables the functioning of rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles, which in turn are key to the planned transition away from fossil fuels. Canada has lithium, but does not necessarily have a comparative advantage in lithium mining, and indeed it seems likely that the world is headed for an oversupply of lithium for the foreseeable future.

If lithium mining cannot be done profitably at current prices in Canada in those circumstances, governments should not subsidize it, unless importing it would be so costly and uncertain as to make investments in other activities for which Canada does have a comparative advantage unattractive. That said, if another country sought to artificially drive down the price of a critical mineral such as lithium in order to corner the market and subsequently restrict access to it, Canada could be part of a price support consortium, to ensure the mineral can be mined economically at home or in a friendly country.

The better solution, from the point of view of economic and supply chain efficiency, would be to address the trade and investment distorting impact of strategic industrial subsidies, before they degenerate into an all-out subsidies war from which few countries can ultimately benefit.19 Canada should make it a priority to support renewed talks (for example, as Chair of the G7 in 2025, or indeed as founder of the Ottawa Group of 14 major trading nations seeking to find consensus for WTO reforms) on disciplines for the use of industrial subsidies, as part of a dialogue on economic security which could in principle appeal even to strategic adversaries. Given fragile fiscal positions, and complaints about the distortionary impact of trade partners’ subsidies, every economy would plausibly be interested in the success of such a dialogue.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have proposed a strategy with ambitious but well-defined goals, and a set of actionable policy directions. We have done so after considering existing and probable sources of supply chain stress, the global reconfiguration of supply chains, and Canada’s vulnerabilities and opportunities. The implementation of this strategy can be further delineated for specific sectors (e.g., Van Assche 2024 concerning supply chains for low-emissions technologies).

It is important – in an age likely to see the United States veering further toward measures impeding the flow of trade – to note that this strategy relies in significant part on aspects that are within Canada’s purview: aspects that, by making Canada stronger, will also make accessing its markets more attractive to trading partners, and give it leverage to help preserve or even enhance the benefits of global – and North American – supply chains.

The proposed plan includes boosting existing efforts to build a more modern and resilient Canadian transport infrastructure and system, addressing regulatory bottlenecks and sclerosis, reinforcing trade alliances and economic diplomacy with trusted partners to better tackle potential shortages, ensuring a vigorous Canadian contribution to the security of domestic and global supply chains, and a more disciplined approach to industrial intervention that can better direct our finite resources to activities that are most likely to be economically rewarding and sustainable within global supply chains. Adopting this set of policy directions should enable Canada to take advantage of supply chain reconfiguration, while reducing its vulnerability to future supply chain shocks – whether related to global health, natural disasters, domestic bottlenecks, protectionist policies, or geopolitical events.

References

Alfaro, Laura, and Chor Davin. 2023. “Global Supply Chains: The Looming ‘Great Reallocation.’” Working Paper No. 31661. National Bureau of Economic Research. September 11. Accessed at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w31661

Altman, Steven A., Caroline R. Bastian, and Davis Fattedad. 2024. “Challenging the deglobalization narrative: Global flows have remained resilient through successive shocks.” Journal of International Business Policy 1-24. Accessed at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s42214-024-00197-0

Australia, Department of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. 2023. “Review of the National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy.” Discussion Paper. Accessed at: https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-freight-and-supply-chain-strategy-discussion-paper.pdf

Australia, Transport and Infrastructure Council. 2019. “National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy: National Action Plan August 2019.” August. Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, Australian Government. Accessed at: https://www.freightaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-action-plan-august-2019.pdf

Baldwin John, and Beiling Yan. 2014. “Global Value Chains and the Productivity of Canadian Manufacturing Firms.” Research Paper. Catalogue no. 11F0027M – No. 090. Economic Analysis Division: Statistics Canada. March. Accessed at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/11f0027m/11f0027m2014090-eng.pdf?st=sBkTIy01

Baldwin, Richard, Rebecca Freeman, and Angelos Theodorakopoulos. 2023. “Hidden Exposure: Measuring U.S. Supply Chain Reliance.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, BPEA Conference Draft, September 28-29, 2023. Accessed at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2_Baldwin-et-al_unembargoed.pdf

Bishop, Grant. 2019. A Crisis of Our Own Making: Prospects for Major Natural Resource Projects in Canada. Commentary 534. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/crisis-our-own-making-prospects-major-natural-resource-projects-canada

Blais-Morisset, Paul, and Sheila Rao. 2024. Reshoring trend? What the evidence shows. Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist. Accessed at: https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/assets/pdfs/economist-economiste/analysis-analyse/reshoring_trend-tendance_rapatriement-eng.pdf

Boileau, David, and Aaron Sydor. 2020. “Vulnerability of Canadian industries to disruptions in global supply chains.” Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist. June. Accessed at: https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/economist-economiste/analysis-analyse/supply-chain-vulnerability.aspx?lang=eng

Blank, Stephen. 2016. “Infrastructure, Attitude and Weather: Today’s Threats to Supply Chain Security.” Canadian Global Affairs Institute and University of Calgary School of Public Policy, Policy Paper. June. Accessed at: https://www.cgai.ca/infrastructure_attitude_and_weather

Brown, Mark. 2024. “Research to Insights: Tracking Canada’s Evolving Supply Chain Links and Their Effects.” Catalogue no. 11-631-X. Statistics Canada. March 15. Accessed at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/11-631-X2024003

C.D. Howe Institute. 2021. “Rebuilding Better: Local Content and Public Procurement Rules.” Policy Seminar Report. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. August 31. Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/conference-report-%E2%80%93-rebuilding-better-local-content-and-public-procurement-rules

Ciuriak, Dan. 2023. “The Economics of Supply Chain Politics: Dual Circulation, Derisking and the Sullivan Doctrine.” Verbatim. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. May 25. Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/verbatim-economics-supply-chain-politics-dual-circulation-desrisking-and

DeLand, Charles, and Brad Gilmour. 2024. Smoothing the Path: How Canada Can Make Faster Major-Project Decisions. Commentary 661. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/smoothing-path-how-canada-can-make-faster-major-project-decisions

European Court of Auditors. 2021. “The EU framework for large transport infrastructure projects: an international comparison.” Review No. 5. Accessed at https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/RW21_05/RW_Transport_flagships_EN.pdf

Evenett, Simon, Jakubik Adam, Martín Fernando and Ruta Michele. 2024. “The Return of Industrial Policy in Data.” Working Paper No. 2024/001. International Monetary Fund. January 4. Accessed at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/12/23/The-Return-of-Industrial-Policy-in-Data-542828

Farrell, Henry, and Abraham Newman. 2023. “The New Economic Security State: How De-Risking Will Remake Geopolitics.” Foreign Affairs, Volume 102 No.6. November/December.

Freund, Caroline, Aaditya Mattoo, Alen Mulabdic and Michele Ruta. 2023. “Is US Trade Policy Reshaping Global Supply Chains?” Working Paper No. WPS10593. World Bank. August 31. Accessed at: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099812010312311610/idu0938e50fe0608704ef70b7d005cda58b5af0d#:~:text=This%20paper%20examines%20the%20reshaping,chains%20remain%20intertwined%20with%20China.

Frittelli, John, and Liana Wong. 2021. “Supply Chain Bottlenecks at U.S. Ports.” Congressional Research Service Insight. November 10. Accessed at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11800

Gereffi, Gary. 2020. “What does the COVID-19 pandemic teach us about global value chains? The case of medical supplies.” Journal of International Business Policy 3(3): 287. Accessed at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7360894/

Global Affairs Canada. 2024. State of Trade 2024: Supply Chains. Office of the Chief Economist. Accessed at: https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/state-trade-commerce-international/2024.aspx?lang=eng

Goodman, Matthew P. 2023. “G7 Gives First Definition to “Economic Security.” Center for Strategic & International Studies Commentary. May 31. Accessed at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/g7-gives-first-definition-economic-security

Grootendorst, Paul, Javad Moradpour, Michael Schunk and Robert Van Exan. 2022. Home Remedies: How Should Canada Acquire Vaccines for the Next Pandemic? Commentary 622. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/home-remedies-how-should-canada-acquire-vaccines-next-pandemic-0

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, and Euijin Jung. 2021. “Scoring 50 Years of US Industrial Policy, 1970-2020.” Peterson Institute for International Economics, PIIE Briefing, November. Accessed at: https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/documents/piieb21-5.pdf

Ilyina, Anna, Ceyla Pazarbacioglu, and Michele Ruta. 2024. “Industrial Policy is Back. Is That a Good Thing?” October 21. Accessed at: Industrial Policy is Back. Is That a Good Thing? | Econofact

Jenkins, Paul, and Mark Kruger. 2024. “Furthering the Benefits of Global Economic Integration through Institution Building: Canada as 2024 Chair of CPTPP.” Verbatim. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, Accessed at: https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/verbatim-furthering-benefits-global-economic-integration-through-institution

Jiang. 2021. Identification of Vulnerable Canadian Imports. Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist. November. Accessed at: https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/economist-economiste/analysis-analyse/id-vulnerables-canadiens-importations.aspx?lang=eng

Jiang, Kevin, and Colin Scarffe. 2021. Canadian Supply Chain Logistics Vulnerability. Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist. June. Accessed at: https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/assets/pdfs/economist-economiste/analysis-analyse/logistics-vulnerability-en.pdf

Khanal, Mukesh, Robert Mansell, and G. Kent Fellows. 2023. “Canadian Competitiveness for Infrastructure Investment.” SPP Research Paper Volume 16:24. Accessed at: https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/NC54-Cdn-Competitiveness-for-Infrastr-Investment-1.pdf

Knutsson, Polina, Annabelle Mourougane, Rodrigo, Pazos, Julia Schmidt, and Francesco Palermo. 2023. “Nowcasting trade in value added indicators.” Centre for Economic Policy Research, VoxEU column, September 26. Accessed at: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/nowcasting-trade-value-added-indicators

Laurin, Frédéric. 2023. « Une critique économique du mode de développement de la filière batterie au Québec ». Note de politique publique, Institut de recherche sur les PME, November.

Levy, Philip I. 2024. “Did Supply Chains Deliver Pandemic-era Inflation?” Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief 24-10. October 2. Accessed at: https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/2024-10/pb24-10.pdf

Luo, Yadong, and Ari Van Assche. 2023. “The rise of techno-geopolitical uncertainty: Implications of the United States CHIPS and Science Act.” Journal of International Business Studies 54(8): 1423-1440. April. Accessed at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41267-023-00620-3

Manak, Inu. 2024. “The Curse of Nostalgia: Industrial Policy in the United States.” Council on Foreign Relations. January 22. Accessed at: https://www.cfr.org/article/curse-nostalgia-industrial-policy-united-states

Mattoo, Aaditya. 2024. “Dialogue with World Bank Senior Economist Aaditya Mattoo on new trade protectionism.” Presentation to the Center for China and Globalization. January 17. Accessed at: CCG in Dialogue with Aaditya Mattoo

Mills, Karen G., Elisabeth B. Reynolds, and Morgane Herculano. 2022. “Small Businesses Play a Big Role in Supply-Chain Resilience.” Harvard Business Review. December 6. Accessed at: Small Businesses Play a Big Role in Supply-Chain Resilience (hbr.org)

National Supply Chain Task Force. 2022. “Action. Collaboration. Transformation. Final Report of The National Supply Chain Task Force, 2022.” Transport Canada. Accessed at: https://tc.canada.ca/en/corporate-services/supply-chain-canada/action-collaboration-transformation

New Zealand, Productivity Commission. 2024. Improving Economic Resilience. Report on a Productivity Commission inquiry. February. Accessed at: https://www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Inquiries/resilience/NZPC_Improving-Economic-Resilience-inquiry-report.pdf

Scarffe, Colin. 2022. “The position and length of Canadian supply chains.” Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist. Accessed at: https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/economist-economiste/supply-chain-chaine-approvisionnement.aspx?lang=eng

Simchi-Levy, David, Feng Zhu, and Matthew Loy. 2022. “Fixing the U.S. Semiconductor Supply Chain.” Harvard Business Review. Accessed at: https://hbr.org/2022/10/fixing-the-u-s-semiconductor-supply-chain