From: Mawakina Bafale, Jeremy M. Kronick, William B.P. Robson

To: Canadians Concerned About Inflation

Date: March 25, 2022

Re: Monetary Policy Is Our Only Inflation Fix

What explains surging inflation in Canada and many other advanced economies? At the moment, a critical mass of commentators blame loose monetary policy. While we agree, the strength of that judgement is surprising. It contrasts with the 1970s and 1980s, when many people argued that inflation was not something central banks could control – and, therefore, that tight monetary policy was pain for no gain.

With the Bank of Canada and other central banks beginning to tighten, those earlier arguments may flourish again. If they prevail, monetary policy will stay too loose, and inflation will keep raging.

For macroeconomists, inflation is another term for a persistent decline in the value of money. The value of money reflects, like anything else, supply and demand. If the Bank of Canada promotes growth in the supply of Canadian dollars that exceeds growth in the demand for Canadian dollars, their value falls compared to the value of the goods and services people use money to buy and sell. The general level of prices rises: that’s inflation.

This macro take, however, is not how people experience inflation. What we notice in our daily lives is movements in individual prices. Gasoline costs more today than the last time we filled up. The higher price of lettuce surprised us on our previous trip to the store – this time, it was milk. As though different products are taking different-size bites out of our dollar at different times, rather than the dollar itself shrinking.

Arguments that inflation is about supply shocks or price gouging for individual items become more attractive when monetary policy tightens, because tight monetary policy hurts. Mortgages with floating rates or coming up for renewal cost more. Business credit gets scarcer. Spending slows or declines, and jobs follow. People want alternatives. Go after the speculators! Subsidize fuel! Slam on wage and price controls! But the experience of the 1970s and 1980s was clear: without tighter monetary policy, inflation stays high.

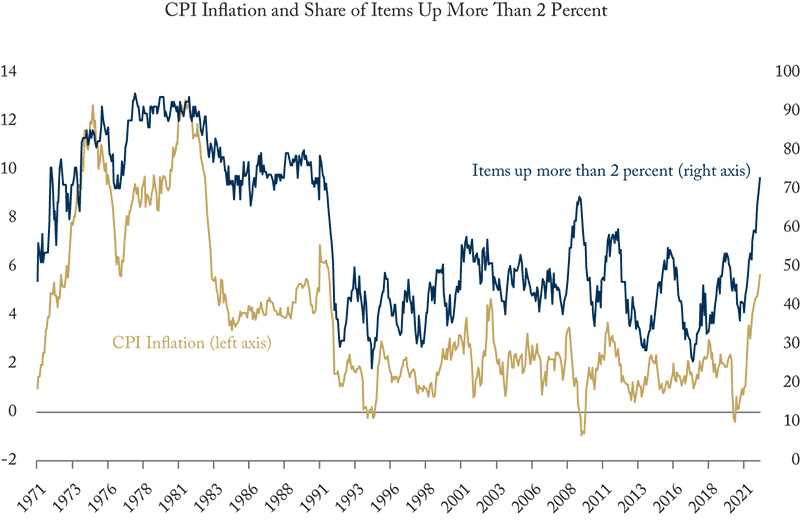

One way to bridge the gap between the macro view and everyday experience is to look at prices across the board. Statistics Canada publishes many CPI sub-indexes: 185 on its website. We can check how many of them are up by more than key amounts, the Bank of Canada’s 2-percent target being an obvious choice. If only a few are, changes in the total CPI might reflect specific circumstances, such as a poor coffee harvest, that will pass in time. If many are, something more systematic is driving the value of the dollar down.

The figure shows, from the early 1970s to the latest reading for February 2022, the familiar measure of inflation, the year-over-year increase in the total CPI, as well as the share of items in the CPI showing year-over-year increases larger than 2 percent. During the period of low and stable inflation from the mid-1990s until last year, the share of items with year-over-year increases above the Bank of Canada’s 2-percent target was – no surprise – usually around half. On occasions when the CPI was up or down by unusual amounts, such as in 2008/09, the share of items up by more than 2-percent helps judgements about whether monetary policy was badly off course – on that occasion, it suggests that the lower CPI readings owed more to peculiar circumstances affecting some items than monetary policy being off course.

During the 1970s inflation, food and energy often made headlines and some people blamed them for inflation, but the share of items up more than 2 percent shows that nearly everything was up nearly all the time. During the 1980s, CPI inflation was lower, but the share of items up more than 2 percent emphasizes the broad-based erosion of money’s value before another round of tightening and the beginning of inflation targeting in the 1990s.

We have just come through two years when the Bank of Canada held its overnight rate close to zero and bought hundreds of billions of dollars in government debt. While the Bank’s response to the pandemic had plenty of justification – many other central banks did the same – the year-over-year increase in the CPI is higher than it has been in 30 years. So is the share of items with year-over-year increases above 2 percent. This is not peculiar circumstances affecting particular items that we can wait to unwind or intervene to fix. Monetary policy determines inflation. It is the best tool we have to fix it.

Mawakina Bafale is a Research Assistant at the C.D. Howe Institute, where Jeremy M. Kronick is associate director, research, and William B.P. Robson is CEO.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.