To: The Hon. Steven Guilbeault, Minister of Environment and Climate Change

From: Brian Livingston

Date: February 14, 2024

Re: Ottawa’s Blind EV optimism

By 2035, only zero-emission cars and light trucks can be sold according to the federal government’s recently finalized mandate regulations.

That leaves just 11 years and reasonable forecasts of production and sales make clear that Ottawa’s timeline is unrealistic.

The mandate states that new light vehicles must be at least 20 percent zero-emission – practically speaking electric vehicles (EVs) – in 2026, 60 percent in 2030 and finally 100 percent in 2035. The theory is that these requirements will guarantee a market for EVs and therefore encourage imports, construction of domestic manufacturing facilities and the phase-out of internal combustion engine vehicles.

And to nail down the outcome, the mandate flat-out prohibits the sale of gas-powered light vehicles in 2035 and beyond.

Canadians bought about 1.5 million cars and light trucks in 2022, according to Statistics Canada. Fifty-six percent were SUVs and crossovers, 23 percent pick-up trucks, 18 percent passenger cars and 3 percent vans. As for power sources, “battery electric vehicles” accounted for 6.5 percent, plug-in hybrids 1.5 percent, gas engines 82 percent and diesel and conventional hybrids 10 percent. Battery EV sales were highest in B.C. and Quebec – both with incentives and mandates – at 13.6 and 9.1 percent, respectively. In the other eight provinces, battery EV sales were well below the overall Canadian average of 6.5 percent. (We don’t have complete 2023 numbers, but a forecast using the actual sales in the first three quarters plus an estimate for the fourth puts battery EV sales at 9 percent of Canada-wide sales, 18 percent in B.C. and 14 percent in Quebec).

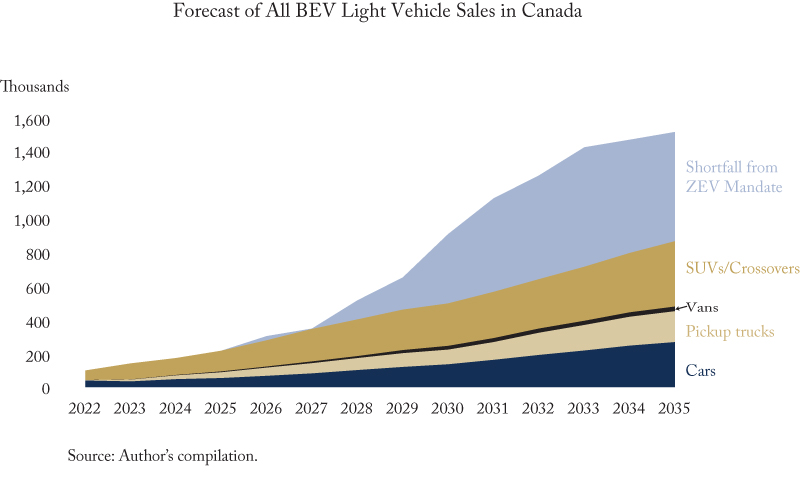

In my new C.D. Howe Institute working paper, I develop a forecast of battery EV sales between now and 2035 using a bottom-up process that looks at the situation of each significant Canadian seller. I examined each supplier’s production and sales plans, made a risk-based projection and then summed up the projections. My estimate is that 860,000 battery EVs are likely to be sold in Canada in 2035 –640,000 less than my assumed forecast of 1.5 million total sales in 2035. Sales in future years may well be higher due to population growth – for example, sales in 2023 are estimated to have been over 1.6 million. If that occurs, it means an even larger shortfall of battery EVs.

That means serious disruption in the market if the estimate is right and production does undershoot desired sales by more than 40 percent. To keep their EV sales at the mandated percentage of total sales, sellers may have to cut back on sales of gas vehicles (until 2035, when they will be required to cease those sales altogether). If the overall demand for light vehicles does exceed overall supply, possibly by a lot, several undesirable things may occur – more imports of slightly used vehicles, longer use of existing gasoline vehicles and an increase in vehicle prices, to name three.

So what is Plan B if the mandate’s rigid objectives can’t be met? Perfect, 100-percent compliance is a laudable goal, but the world is seldom perfect. The federal government needs to be flexible.

To that end, Ottawa should consider letting plug-in hybrids count as EVs. The current rules cap them at 20 percent of sales. Ottawa should scrap the cap.

There are serious concerns on the demand side, too. Battery EV sales have faced resistance recently, particularly for pickup trucks. Ford recently announced it would cut production of its F150 Lightning to just one shift as of April 1, down from three as recently as last summer.

Instead of forcing adoption of battery-powered vehicles, a better policy would be to encourage manufacturers to increase the range of plug-in hybrids (particularly pickups) to say, 200 kilometres. These higher-range plug-in hybrids would be an easier sell, particularly to rural buyers worried about range, insufficient charging infrastructure and long charging times. Plug-in hybrids could well operate more than half the time using batteries rather than gas, which would reduce emissions considerably – a good (if not perfect) result.

Another option is to count conventional hybrids as EVs. Canadians bought more than 81,000 of them in 2022, only slightly fewer than their purchases of battery EVs. Conventional hybrids aren’t perfect, but the US energy department estimates they can achieve 35 percent better fuel efficiency than straight internal combustion vehicles.

Finally, Ottawa should recognize that some ICE light vehicles probably will need to be sold in and after 2035. Canadian policy should follow the recent decisions of the EU and U.K. and make the phase-out of ICE vehicles more gradual, particularly those that can run on renewable fuels.

After a realistic look at the numbers, it’s hard not to conclude that Ottawa’s current EV plan is rigidly ideological. Policymakers would be better advised to back off the perfect 100 percent zero-emissions requirement for 2035 and instead accept that a less ambitious target is more realistic and still yields a good result.

“Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” is a rule-of-thumb most Canadians understand. They should remind Ottawa what it means.

Brian Livingston, executive fellow at the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

A version of this Memo first appeared in the Financial Post.