From: Don Drummond and Benjamin Dachis

To: Ontario debt watchers

Date: April 5, 2023

Re: The Ontario Budget Needs Program Reform Action

Ontario’s budget projection of small surpluses after next year allows the government to claim progress toward fiscal stability and bettering Ontario's economy.

But it deflects attention from the far more significant economic indicator – the net debt-to-GDP ratio.

The budget last month projects a modest decline in the short run. The government can claim a “victory” of sorts. A longer-term perspective is needed, and deep program reform is the only way to realizing a sustainable fiscal outlook and serving the people of Ontario.

The Ontario net debt burden has been following a step pattern, jumping up with each economic/fiscal shock, remaining at the higher level and jumping again at the next. It was just above 10 percent in 1990; it climbed to around 32 percent by 2000. Despite the good economic times then, the ratio declined only slightly until the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing recession. Then it jumped up to around 40 percent where it has remained. Even if it does decline to 36.9 percent by 2025-26 as projected, that is more than triple Ontario's net debt-to-GDP ratio as recently as 1990. Like Ottawa, the province will be in a very risky position when, not if, the next shock hits.

Source: Ontario 2023-24 budget.

*Recession dating according to the C.D. Howe Institute Business Cycle Council

This level is high in absolute, historical, and relative terms.

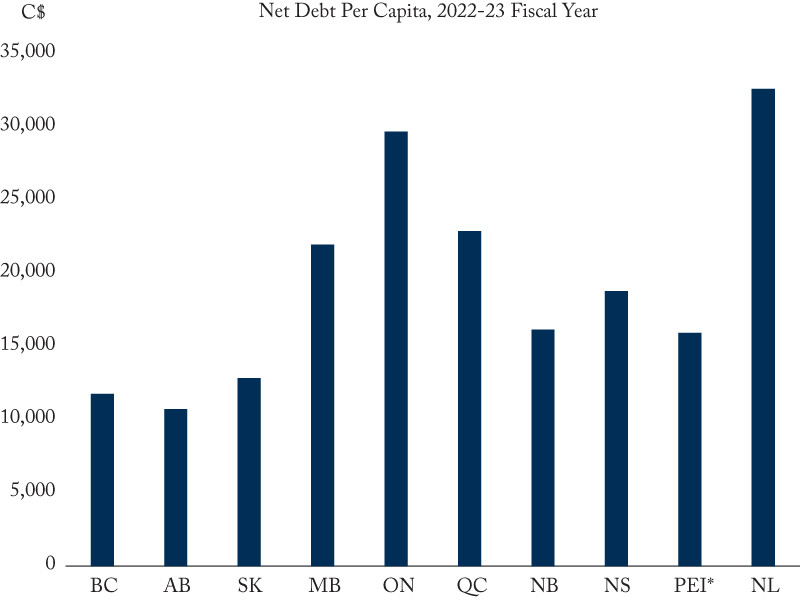

Interest rates are unlikely to return to the lows of recent years that allowed the province to carry high debt. This level of debt will require a large and almost certainly increasing share of resources to service it. A net debt ratio of almost 40 percent puts Ontario up with provinces typically thought to have more challenging fiscal situations, such as Newfoundland & Labrador. It far exceeds the debt burdens of BC, Alberta, and Saskatchewan. Ontario’s debt ratios are even higher than New Brunswick, Nova Scotia. and Prince Edward Island, reversing traditional rankings.

Source: RBC Economics. Note: PEI figures are for 2021-22.

Getting the debt burden down to more manageable levels will require many years of significant surpluses, a standard against which this and future Ontario budgets should be judged. Spending growth is the principal obstacle to restoring a sounder fiscal position for Ontario. From a pre-COVID base in 2019-20, the province projects base program (excluding COVID and other ‘one-time’ items) spending to grow at an annual average pace of 4.9 percent through 2025-26.

It may not be surprising that health spending leads the charge from this base at 5.4 percent annual growth. However, the fastest growing component, at 7 percent, is “other programs” which excludes health, education, post-secondary education, children, community and social services, and justice. The annual growth of “other programs” is 12 percent or more each year from 2020/21 to 2023/24.

Ontario should be commended for showing a more realistic growth profile for future health spending than the previous budgets that forecast unrealistic projections of just over 2 percent per annum. The current budget forecasts the total pace of health care spending growth to be 5.4 percent 2022-23 to 2025-26. That exceeds revenue growth of 4.1 percent over that same period. Planned spending growth in education at 5 percent annually the next three years is also realistic given the post-Bill 124 reality. But the government needs to find a way to bring ‘other program’ spending growth back down from its pandemic-fuelled growth in recent years to a more sustainable pace of at or below the planned 2 percent or less until the next election.

Ontario needs to bring the net debt-to-GDP burden to below 30 percent within the next five years and subsequently to 20 percent or less – a level still almost double that at the beginning of the 1990s. Program spending growth will need to be much more modest than projected in the new budget. That means years of running surpluses – not just being satisfied with balanced budgets.

How do we get there? There are considerable spending pressures, not the least of which is 2.2 million Ontarians without a family doctor. Many others are in dire need of home and community care. These programs need fundamental reform to achieve greater efficiency and efficacy.

Population growth and demand for infrastructure is relentless. We need to rethink how we build and finance infrastructure and provide services. As we both know firsthand, program reform is very hard. Only with hard work and new ideas coming in can governments spend less without affecting the services the people of Ontario need. Some positive steps are underway, such as expanding the scopes of practice of some health professionals and creating more health teams. But much, much more is needed, in health and everywhere else to boost productivity of public services.

The Commission on the Reform of Ontario’s Public Services recommended reforms to achieve such spending restraint. But few were adopted by successive governments. Several of the short-cuts taken instead, such as lowering physician compensation and over-riding collective bargaining agreements, backfired. Eleven years later, the Commission’s report looks like sound advice not taken. Better late than never.

Don Drummond is the Stauffer-Dunning Fellow, Queen’s University and Fellow-in-Residence, C.D. Howe Institute and Benjamin Dachis is Associate Vice President of Public Affairs at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.