From: Jeremy M. Kronick and Nikki Hui

To: Federal, Provincial, and Municipal Policymakers

Date: July 11, 2018

Re: Housing Supply Is the Fix to High Household Debt

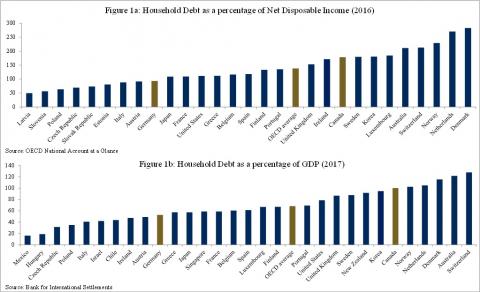

Canadians often get flagged for sitting on mountains of household debt, and being in danger of facing a reckoning if interest rates rise, or worse, if a recession hits. Largely, this is measured by ratios such as household debt to disposable income and household debt to GDP, which show that Canadians are highly leveraged when compared to other OECD countries (Figure 1).

It is worth asking then, what distinguishes Canada from less leveraged countries?

Such an empirical exercise often assumes that household debt to disposable income and household debt to GDP are the right ways to assess optimal debt levels. But not everyone agrees.

For one thing, these measures are not an accurate reflection of affordability. Perhaps a more accurate measure is Canada’s debt servicing ratio, which has been flat for the last decade, and sits approximately where it did in the early 1990s.

Furthermore, if we control for Statistics Canada’s main determinants of household debt – measures such as income, education, and immigration – Canada’s household debt to disposable income sits well below where one might expect.

But for the purposes of this exercise, let’s assume debt to disposable income and debt to GDP paint a pretty good picture of where Canadian households’ debt exposure sits relative to the rest of the developed world. And let’s compare Canada to Germany, a G7 peer with significantly lower household debt ratios.

The GDP of the two countries has grown at a similar pace the last decade or so, as has disposable income. So the difference in the ratios must come from the numerator: household debt. On the demand side, labour force data are strong in both countries: both Canada and Germany rank above the OECD average in participation rates for prime working-age 25-54 year olds, employment to population ratios of these same prime working-age folks, and in foreign-born employment rates, according to OECD numbers.

One big difference, however, is the homeownership rate. In Canada, 70 percent of the population owns a home, with 40 percent holding a mortgage. Germany, on the other hand, has only a 45 percent homeownership rate, and 20 percent with a mortgage. So, despite OECD data showing similar median monthly mortgage spending relative to disposable income, aggregate debt in Germany is smaller.

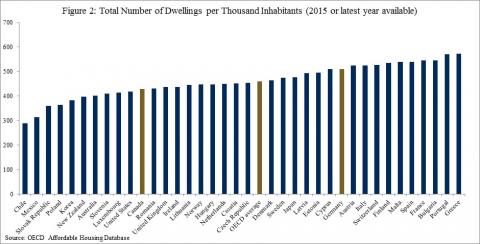

On the supply side, there is also a stark difference, as Germany’s total number of dwellings per 1,000 inhabitants is 20 percent higher than Canada’s (Figure 2). This is consistent with the idea that many cities across Canada face significant barriers to increased housing supply, largely a result of excessive regulations.

What this simple exercise suggests is that both demand and supply side differences may explain the gap in household debt ratios between Canada – a notoriously high household debt country – and Germany – a low household debt country. Assuming we cannot change people’s desire to own homes, one clear option is to remove regulatory barriers and increase the number of dwellings. It doesn`t matter if they are for ownership or rental, we just need to build them.

For more on household debt in Canada, see our Graphic Intelligence, Explaining Household Debt – Canada vs. Germany.

Jeremy M. Kronick is Associate Director, Research and Nikki Hui is a Researcher at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.