From: Ted Carmichael

To: Canadian inflation watchers

Date: June 21, 2023

Re: How to Tame Inflation Without Breaking the Economy

The trigger for the sharp rise in Canadian inflation in spring 2021 is still debated. And it’s a debate that matters: The relative importance of the pandemic supply chain disruption, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, “greed,” or central bank financing of a surge in government spending will affect our response to future events. But once inflation gets started, its initial causes are less important than the process that sustains it, which is a combination, on the one hand, of rising inflation expectations and costs and, on the other, of inadequate production.

When inflation has been low and stable – say 2 percent – for some time then everyone knows that inflation will be about 2 percent and behaves accordingly. It’s common knowledge.

But when something disrupts that stable behaviour – a pandemic, a war, a big increase in government spending with deficits financed by central bank bond purchases – behaviours change.

First comes the response in markets with flexible prices: Oil, copper, lumber, wheat and other high-demand commodities. As raw material prices rise, processors and manufacturers who use them raise their prices to cover increased costs. If the inflationary shock arrives at a time when aggregate demand exceeds aggregate supply, as it did in Canada in 2020-21, the initial shock is passed through to prices of other goods and services. (If there’s excess supply in the economy, the price increase is muted or takes the form of a slower reduction in prices than would otherwise have taken place.)

When there is this excess demand, workers who see their real income and standard of living being reduced by rising prices respond, not surprisingly, by seeking higher wages to catch up.

If the price rises persist, common knowledge and expectations begin to change. Every business knows that other businesses are raising prices to maintain profitability. Every worker knows that other workers are asking for a faster pace of wage gains and are changing jobs, if need be, to get them. That is the situation we currently find ourselves in. Common knowledge has changed and inflation expectations appear to have increased to well above the stable 2-percent target to which we grew accustomed between 1995 and 2020.

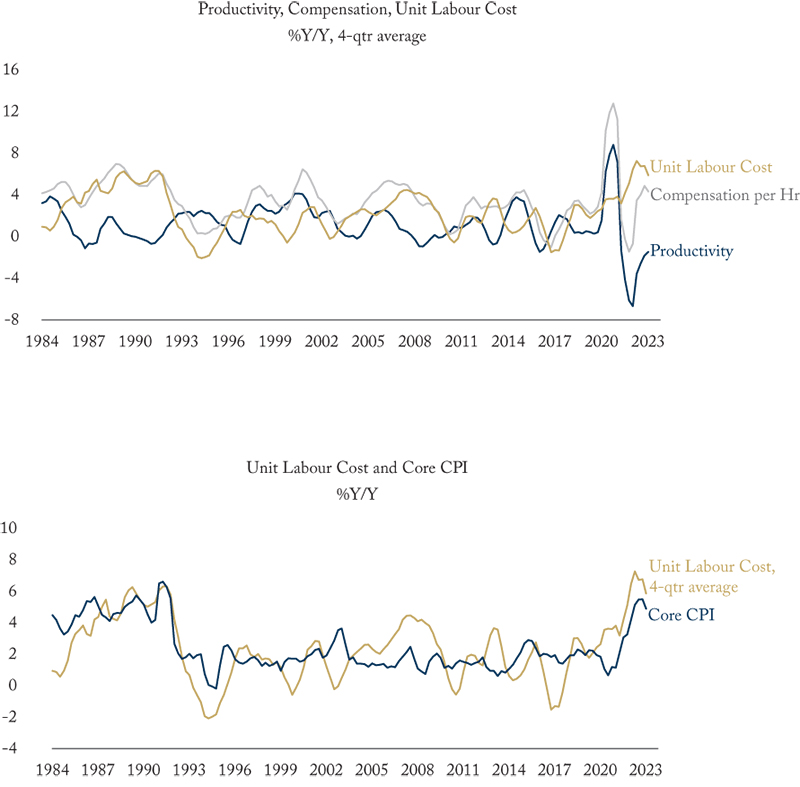

Inflation gathers momentum when total compensation per worker outpaces the growth of output per worker, or productivity. A useful measure for capturing this relationship is growth in unit labour costs. When inflation picked up in the 1980s, hourly compensation outstripped productivity and unit labour costs grew by as much as 6 percent per year. The 1990-91 recession pushed up unemployment and slowed wage growth, and productivity rose as the economy recovered, driving unit labour costs down. From 1992 through 2019, growth in unit labour costs averaged around 1.5 percent per year, while inflation stayed close to the Bank of Canada’s 2-percent target –a stable process supported by expectations of 2-percent inflation and modest, but positive, gains in productivity.

The recent inflationary shock pushed Canada back into a situation more like the 1980s. Compensation is rising, but productivity is not. The latest data – from the first quarter – are worrisome with compensation per hour growing at a 4.3-percent pace and productivity falling at a 1.5-percent rate, resulting in unit labour cost growth of 5.9 percent.

No wonder core CPI is up!

Breaking the momentum of Canada’s inflation will require some combination of slower compensation growth and faster productivity growth. Neither will be easy, and the inflationary late 1980s and recessionary early 1990s are both episodes we would like to avoid. Milder restraint of demand than took place in the late Mulroney years, combined with policies that boost investment and productivity, could hit the economic sweet spot of rebooting expectations without a recession.

The Bank of Canada has been restraining demand with higher interest rates. But recent federal and provincial budgets have done more to stoke demand with higher spending and borrowing than to boost productivity with investment-friendly tax and regulatory relief. For inflation to return to 2 percent, fiscal and regulatory policies need to do more to ensure the faster productivity growth that will help break inflation’s momentum.

Ted Carmichael is a member of the C.D. Howe Institute Monetary Policy Council.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

A version of this Memo first appeared in the Financial Post.