From: Werner Antweiler

To: Food price observers

Date: November 27, 2023

Re: Unpacking the Real Sources of Rising Food Prices

Consumers are complaining about high food prices, and indeed food prices have risen sharply since the end of the pandemic.

Politicians have taken up the complaints. Liberals in Parliament have singled out record profits of grocery chains and the lack of competition in Canadian food retailing, implicitly portraying these companies as greedy. Meanwhile, Conservatives blame Liberals and have cite the federal carbon tax as a scapegoat. Both parties are a fair bit off the mark.

Politicians cannot magically lower food prices, and the carbon tax has a negligible impact. Food retailing is not a high-margin business, and retailers have indeed been facing higher costs due to the effects of climate change on agricultural production, supply chain bottlenecks, the effect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, higher energy prices, and higher wages in response to higher inflation.

The only market segment where food prices are regulated are where supply management for dairy and poultry products keeps prices artificially high, but politicians are loath to reform supply management (see my recent discussion on dairy imports). There is in fact a link between food prices and a specific climate-related policy, to which I return below, but it is not carbon pricing.

But how much have different food categories really risen in recent years? Simply looking at the most recent annual inflation numbers distorts the picture because the baseline changes from one month to the next. It is more useful to examine the rise of food prices over a longer period.

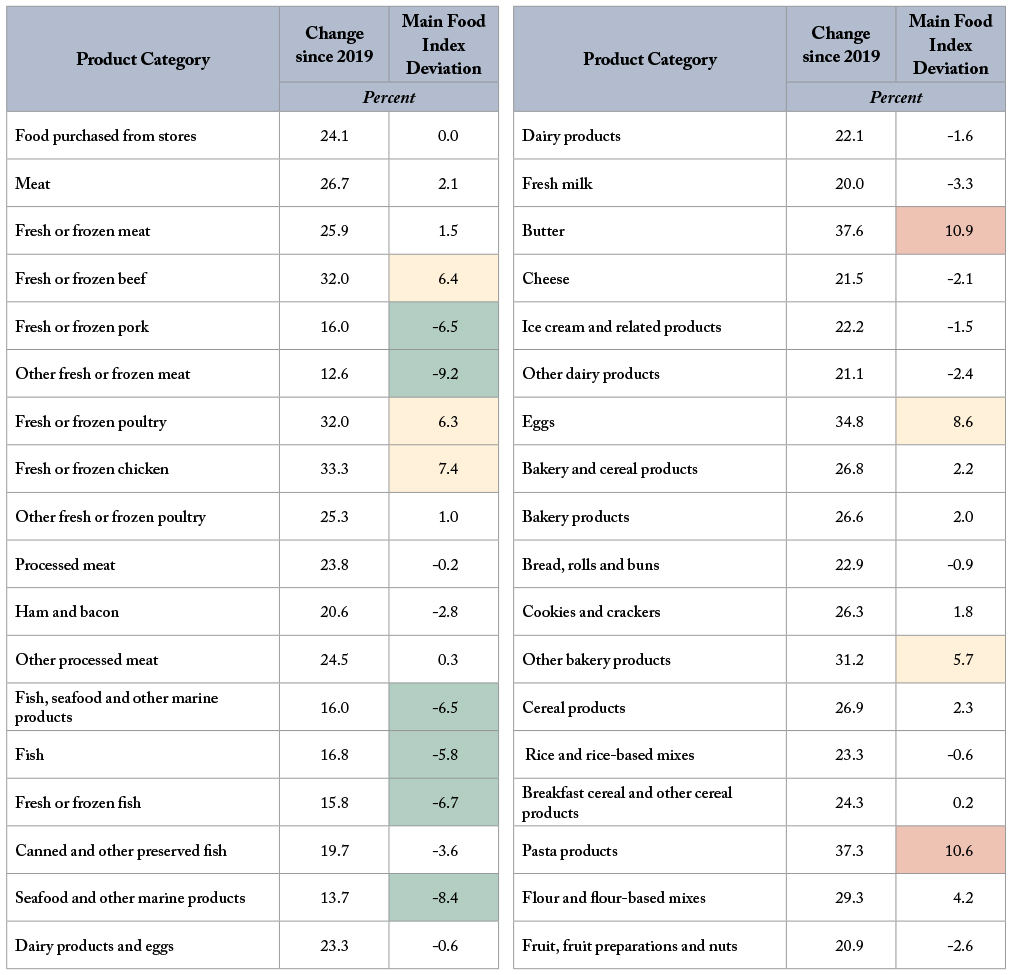

Statistics Canada collects monthly food price information in order to compute the Consumer Price Index, and specifically table 18-10-0004. The CPI data are quite detailed if one is willing to look closely. Below I have compiled a table with the most recent data from September 2023, and compared this against a reference period, the average of 2019. For each food category I show the percentage increase since 2019 and the percentage deviation from the Main Food Index, the first row in the table. Differences are calculated as a percentage deviation, not simply the percentage-point difference.

Overall, food prices have risen 24.1 percent over the course of four years, an annualized inflation rate of 5.5 percent. In fact, all food items have risen in price; nothing has gotten cheaper.

The table shows which food items have risen more than the average food item, and which have risen less. A red background indicates deviations of more than 20 percent, an orange background indicates deviations of more than 10 percent, and a yellow background indicates deviations of more than 5 percent. Items with negative deviations of more than 10 percent and 5 percent are indicated by dark and light green backgrounds, respectively.

Some items are vastly more expensive, especially edible fats and oils. Margarine is 67 percent more expensive than four years ago. This price increase seems to have spilled over into the price of butter, which has risen 38 percent over four years.

Some food items have not risen quite as fast as others. Surprisingly, fresh vegetables including tomatoes, potatoes and lettuce seem to remain more affordable, as well as some fresh fruit such as bananas. Among the meats, beef and chicken is relatively more expensive than pork. And looking through the remainder of the list, pasta products have risen more than other food items, as well as frozen and dried vegetables, fruit juices, and eggs.

What stands out is the incredibly high price of oils and fats (including margarine). Agrifood experts point to a combination of tightening supplies and growing global biofuel targets. Argentina's soybean crop for 2023 was dismal, and output in other Latin American countries is also lower than expected. Demand from China has also rebounded from pandemic conditions. And there are signs that the biofuel industry is approaching a feedstock crunch. Consumption of vegetable oil for biofuel production is expected to increase 46 percent to 54 million tonnes over 2022-2027, the International Energy Agency reported last December, raising the share of vegetable oil production directed to biofuels from 17 percent to 23 percent. In the United States, this increase in demand is already reducing soybean oil export estimates and supporting higher prices.

Rising biofuel demand putting pressure on food prices is not new. Ethanol-blending mandates for gasoline, and airlines demanding more sustainable aviation fuel, are contributors and 40 percent of US corn is already used to produce biofuels. A recent report by the US Department of Agriculture also linked the growing demand for fats and oils on the global biodiesel expansion. Most of the feedstock comes from crude palm, soybean, and canola oils. While global ethanol consumption has been relatively flat in recent years, biodiesel consumption is rising.

There are other notable factors contributing to high food prices. Russia’s war on Ukraine has disrupted grain supplies, wheat in particular. Blocked Ukrainian grain shipments are worsening global starvation. World markets for fertilizers have been disrupted as well; Russia is a major exporter of urea. All these factors have driven up production costs for Canadian farmers. Farm input prices have risen by 29.3 percent between the second quarters of 2019 and 2023; fertilizer alone is up 51 percent over the same period.

The blame for high food prices falls neither on greedy retail chain CEOs nor on Canada’s carbon tax. Most contributing factors can be attributed to global sources. The Ukraine war has driven up fertilizer and grain prices, along with energy prices.

But we also need to look at the unintended consequences of well-intentioned biofuel mandates. Simply diverting more and more agricultural production towards biofuels will ultimately have even higher impacts on food prices. The current rise in prices for fats and oils appears to be at least in part influenced by this trend.

Breaking the link between rising biofuel demand and food prices requires capturing biomass that is a co-product (or waste) of existing agricultural production, such as crop and wood residue, including corn husks and stalks. Biofuel production needs to rely on feedstocks that do not reduce cropland. Public policies directed at biofuels need to distinguish between sources that affect food prices and the sources that do not.

Werner Antweiler is an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia where he holds the Chair in International Trade Policy.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.