Executive Summary

In the decade leading up to the pandemic, safe assets did not keep pace with global demand. The supply of high-grade government bonds in advanced economies was constrained because budget deficits were declining. At the same time, the demand for these assets increased due to the aging population, more restrictive regulations on financial institutions (requiring them to hold more safe assets) and the rapid growth rates in high-saving emerging markets with underdeveloped financial markets, notably China.

In our paper, we show this was true in Canada as well. And, despite interest rates on the rise and governments issuing tons of debt during the pandemic, the safe asset shortage is likely not a one-off phenomenon of the years between the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the pandemic. It is important, therefore, to have a general understanding of how the shortage might impact economic growth and what drives the scarcity in the first place.

We investigate whether a shortage of safe assets – both global and domestic – had a negative impact on the Canadian economy and find that it did. This investigation fills an important gap in our knowledge as the vast majority of previous studies on the macroeconomic impact of safe asset shortages have focused on the US. Another novel contribution is we empirically investigate the drivers of country-specific safe asset shortages and discuss policy implications.

Three key policy implications emerge for Canada. First, it is not viable to increase the supply of Canadian safe assets by increasing Canadian government debt so that it would meet the excess demand for those assets. Although it might help to reduce the shortage of Canadian safe assets in the short-run, it can come at the expense of Canadian output, particularly when the government debt-to-GDP ratio is high.

Second, loosening domestic regulatory requirements is unlikely to alleviate any shortage of Canadian safe assets. Furthermore, it will likely have no effect at all on the global shortage of safe assets. This is because Canada is a small, open advanced economy, and any action that we take in this regard, if it is to be consequential, must be done in concert with our peers on the international stage.

Finally, if Canada wants to address its domestic safe asset shortage, it needs to work with other economically significant economies in fora such as the G7, the G20 and the BIS to address the global safe asset shortage. And Canada must do this in tandem not only with other advanced economies, but also with large emerging markets on the demand side. Both the large demanders and large suppliers of safe assets must work together in order to address this global safe asset shortage.

The authors thank Mawakina Bafale for his research assistance. Kronick and Wu acknowledge the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for financial support [grant numbers 1008-2020-1150, 2020].

1. Introduction

Safe assets – debt instruments that are expected to preserve their nominal value during both good times and bad, and have ample liquidity – play a vital role in the financial system. Institutions use them to store wealth, meet regulatory requirements and provide collateral in financial transactions. Safe assets typically fall into two categories: public and private. Public safe assets include government debt, safe because of governments’ power to tax households and businesses. Private safe assets also include highly rated debt, mostly from the financial sector where institutions are subject to strict prudential regulation.

Between the 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) – perhaps even earlier – and the COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2020, the supply of safe assets did not keep pace with global demand (Habib, Stracca, and Venditti 2020). Historically, a small number of advanced economies, most prominently the US, have supplied safe assets to the world economy. But in the decade leading up to the pandemic, the supply of high-grade government bonds in advanced economies was constrained because budget deficits were declining. At the same time, the demand for these assets increased due to the aging population, more restrictive regulations on financial institutions (requiring them to hold more safe assets) and the rapid growth rates in high-saving emerging markets with underdeveloped financial markets, notably China.

A safe asset shortage can have important macroeconomic consequences. They have been associated with financial instability and crises, which are detrimental to GDP growth (Gourinchas and Jeanne 2012). Moreover, the scarcity of safe assets has been found to be an important driver of the decline in neutral interest rates – where the economy is at potential and inflation is stable – in advanced economies (Ferreira and Shousha 2020). The scarcity has also been identified as a key factor explaining the so-called post-GFC secular stagnation in advanced economies, characterized by low capital investment, slow GDP growth and low interest rates (Summers 2016). And, as shown by Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas (2017b), this negative impact on GDP can be more pronounced when monetary policy is operating close to the policy rate's effective lower bound (ELB).

In this situation, real interest rates on safe assets have limited room for downward adjustment, leaving the economy with higher rates relative to their equilibrium values.

Of course, with interest rates on the rise and governments issuing tons of debt during the pandemic, safe assets may no longer be scarce (Davies 2020). But whether this increase in supply has reduced or eliminated the global asset shortage is an open question, as it will depend on how much supply has risen and, critically, whether this increased supply has kept pace with increased demand. At the time of writing, with the Bank of Canada and other central banks aggressively hiking interest rates to tame well-above-target inflation, we may find ourselves in a recession in short order. If that occurs, demand for safe assets will only increase.

The point is that the safe asset shortage is likely not a one-off phenomenon of the years between the GFC and the pandemic, and it is important, therefore, to have a general understanding of how it might impact economic growth and what drives the scarcity in the first place.

In our paper, we show that Canada has experienced periods of safe asset shortages over the past few decades. We then empirically investigate whether a shortage of safe assets – both global and domestic – has had a negative impact on the Canadian economy. In doing so, our paper fills an important gap in our knowledge as the vast majority of previous studies on the macroeconomic impact of safe asset shortages have focused on the US. Insights from our paper are relevant not only for Canada but also for other small, advanced open economies. Another important contribution is that we empirically investigate the drivers of country-specific safe asset shortages and discuss policy implications. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first to do so for Canada and one of only a few studies to examine this question empirically for any country.

More specifically, we focus on two questions, using Canadian data over the period from March 1990 to December 2020. First, we explore and find that a safe asset shortage in a small open economy like Canada’s negatively impacts real GDP, and this effect is stronger when monetary policy is operating close to the ELB. While we are obviously in the midst of a tightening monetary policy cycle and far from the ELB, we have hit the ELB twice in the past 15 years after never having hit it before. It is, therefore, important to have a strong grasp of how different macroeconomic conditions impact macroeconomic variables of interest.

Second, we formally assess the different asset shortage explanations for Canada to gain insights into which factors might drive the scarcity. Although we find that Canada’s safe asset shortage is explained by many factors, there is clearly a dominant impact from the global shortage. Or in other words, we find that the global safe asset shortage is a key driver of the Canadian safe asset shortage. This discovery has very important policy implications. Notably, it suggests that a Canadian shortage cannot be addressed solely by improvements to domestic factors. Canadian policymakers must also work with their counterparts in other advanced economies and emerging markets to address the global safe asset shortage. We discuss the policy implications of this key finding after presenting our main empirical results.

Our paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we empirically identify periods in which Canada experienced a safe asset shortage. Section 3 reviews the relevant literature, focusing on papers that have examined the macroeconomic consequences of a safe asset shortage. In Section 4, we briefly describe our methodology and data set, with the bulk of the details relegated to Appendices A and B. In Section 5, we present our key empirical results. Policy implications are discussed in Section 6, and Section 7 concludes.

2. Identifying Periods of Safe Asset Shortage

In this section, we identify periods over the past few decades in which Canada has experienced a safe asset shortage, including during the early parts of the pandemic. We also pinpoint periods that were characterized by a global safe asset shortage, using the US as a proxy for the world.

We follow the approach used by Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas (2017b) and Gorton, Lewellen and Metrick (2012) who define a shortage as a period characterized by a stable share of safe assets relative to total assets along with a widening yield spread between the expected return on equity and the risk-free rate. This method is based on the premise that although a widening spread could be caused by different factors, it is indicative of a safe asset shortage when demand for safe assets increases beyond what is available.

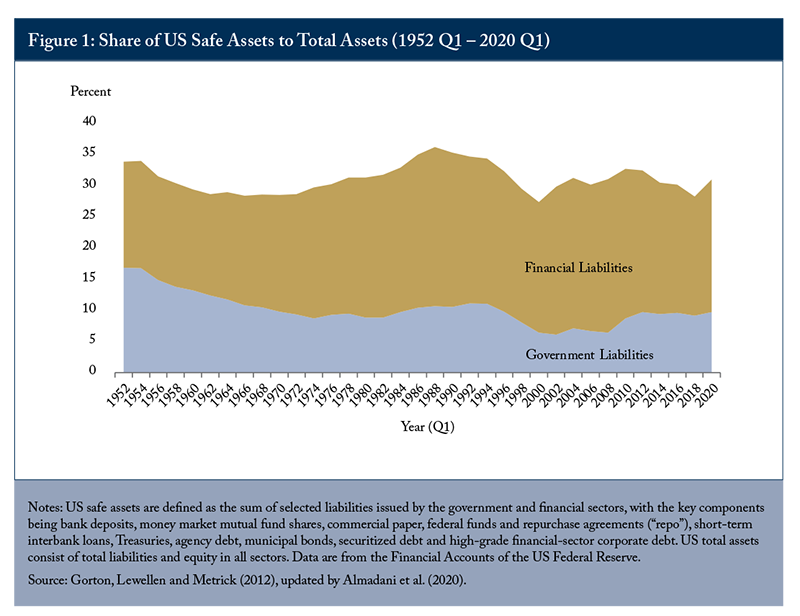

We first demonstrate that the supply of safe assets as a proportion of total assets has been fairly stable over time, both in the US (our proxy for the world) and Canada. Following the taxonomy used by Gorton, Lewellen and Metrick (2012), we borrow the update from Almadani et al. (2020) for the ratio of total safe assets to total assets in the US economy. As shown in Figure 1, this share has fluctuated within a tight band of roughly 30 percent to 35 percent in the post-Second World War period.

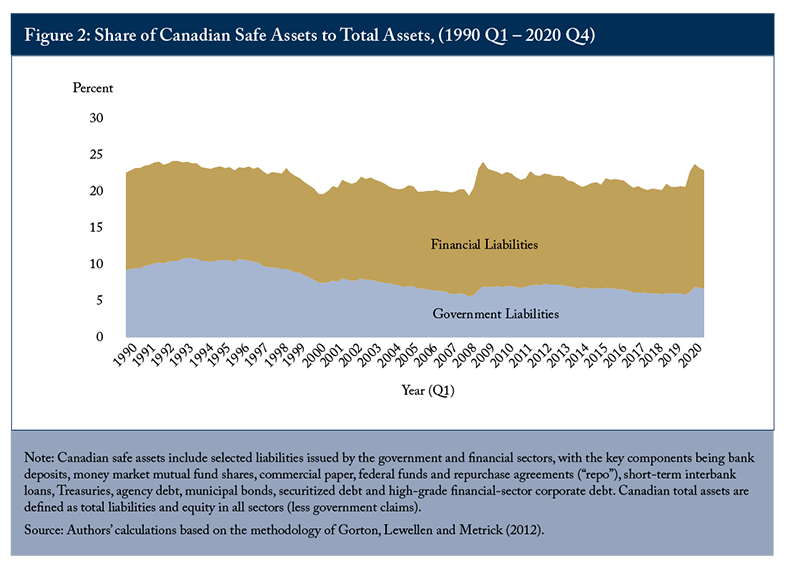

We follow the same approach with Canadian data and find that the proportion of safe assets to total assets in the Canadian economy has also been quite stable, up to and including the early part of the pandemic era (Figure 2).

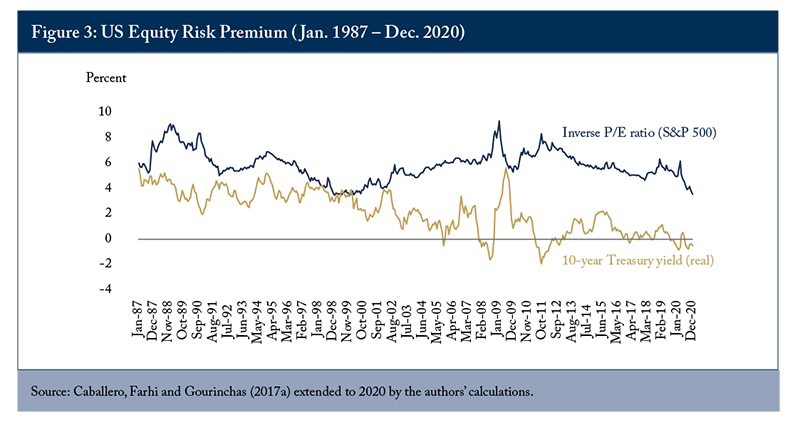

Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas (2017a) show that the widening equity-risk premium is evident for the US, using either sophisticated econometric techniques or a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation of a widening spread between the inverse of the price/earnings ratio on the S&P 500 and the 10-year Treasury yield (real). The latter is shown in Figure 3, in both the lead up to the GFC (2002-2007) and in the post-GFC (after 2009) period.

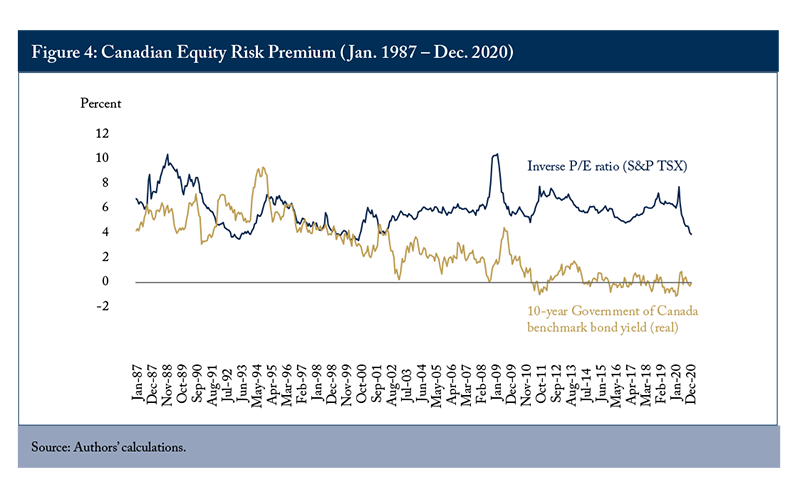

Figure 4 replicates this graph for Canada. As shown, the Canadian pattern is similar to that in the US.

3. Macroeconomic Consequences of Shortages

In the previous section, we identified periods, both in Canada and globally, that were characterized by a safe asset shortage. We also ascertained that this scarcity of safe assets continued during the pandemic, despite the increase in government debt in advanced economies. We now turn to a discussion of the macroeconomic consequences of a safe asset shortage and the underlying drivers of the scarcity.

The literature has shown that a safe asset shortage can have important macroeconomic consequences. First, it has been associated with financial instability and crises, which are detrimental to GDP growth (Gourinchas and Jeanne 2012). A safe asset shortage increases the price of safety and creates an incentive for investors to move down the safety scale, leading to short-term volatility jumps, herding behaviour and runs on sovereign debt (IMF 2012). Meanwhile, Kim (2020) finds evidence that a high level of private credit at a time of increasing safe asset shortage is the major predictor of financial crises in a sample of 17 advanced economies.

Second, in a world in which investors show a particular interest in holding safe government assets, the supply of these assets may be important in determining neutral interest rates. Ferreira and Shousha (2020) formally test this hypothesis in a sample of 11 advanced economies, including Canada’s. They construct a measure of the net supply of safe assets and find evidence that their scarcity is an important driver of the decline in neutral interest rates.

Finally, the scarcity of safe assets has also been identified as a key factor explaining the secular stagnation in advanced economies since the GFC, characterized by low capital investment and slow GDP growth rates (Summers 2016). And as shown by Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas (2017b), this negative impact on GDP can be more pronounced when monetary policy is operating close to the ELB. In this situation, real interest rates on safe assets have limited room for downward adjustment, leaving the economy with higher rates relative to their equilibrium values. When safe interest rates are above their equilibrium value, households prefer to save and delay consumption. Also, as a result, businesses delay investment as they are faced with lower demand for their products and services (and lower business investment). Aggregate demand, therefore, weakens, and the economy can find itself operating below potential. This output loss leads to a loss in total savings. The result is the so-called paradox of thrift.

Domestic options to escape a safe asset shortage require either an increase in the supply of, or a reduction in the demand for, safe assets. Research exploring the effects of increasing supply finds an unsurprising conundrum (Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas 2017b). That is, when governments increase the public supply of safe assets (i.e., government debt), this risks crowding out other forms of investment including financial sector lending financed by short-term debt (Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen 2015). However, safe asset supply increases do not solve the structural problem but merely postpones it (Stein 2012).

Moreover, increasing government debt might have long-lasting side effects on the economy. Acharya and Dogra (2020) demonstrate in a theoretical model that although higher government debt satiates the demand for safe assets, it entails permanently lower investment, which reduces welfare. They suggest that the side effects caused by an increase in safe asset creation in response to the GFC might explain why many advanced economies’ investment and labor productivity remain persistently below pre-GFC trends. Furthermore, when public debt increases above a certain level, it likely slows the pace of recovery (Jordà, Schularick, and Taylor 2016; Reinhart, Reinhart and Rogoff 2012). For his part, Schuknecht (2018) argues that more public debt will not always provide more safety: countries face a kind of “safe assets Laffer curve,” with a maximum amount of safe assets at some level of indebtedness.

On the demand side, there are three major considerations. First, there is an exchange-rate effect whereby an appreciation of the domestic currency reduces foreign demand for safe assets because it increases the real value of those assets from the foreigners’ perspective. Hence, they would demand less of those assets to maintain an optimal share of Canadian assets in their portfolios.

Second, the populations of many countries, including Canada’s, are aging. As the population ages and more people retire, there is a portfolio rebalancing effect as agents replace riskier assets with safer ones, thereby increasing aggregate demand for the latter. And, lastly, financial regulatory requirements, both domestic and international, have tightened in the post-GFC period. Financial institutions are, therefore, required to carry more high-quality liquid assets on their balance sheets than prior to the GFC, resulting in an increase in the demand for safe assets.

Canadian policymakers must also consider the impact of the global asset shortage on the domestic one. It might be the case that Canada, as a small open economy, could fully address all domestic factors contributing to its own safe asset shortage, yet still face a shortage simply due to this global imbalance.

4. Methodology/Data

So far, we have provided evidence suggesting that Canada experienced a safe asset shortage in the pre-pandemic period, and that this shortage continued into the pandemic. As mentioned above, Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas (2017b) argue that a safe asset shortage occurs when relevant interest rates are not able to adjust to clear markets, meaning their level sits above the equilibrium real rate.

For our part, we seek to fill two gaps in their work. First, we explore whether a safe asset shortage in a small open economy like Canada’s negatively impacts real GDP when real interest rates hit zero. Second, we formally investigate the different asset shortage explanations to gain insights into which factors drive the shortage.

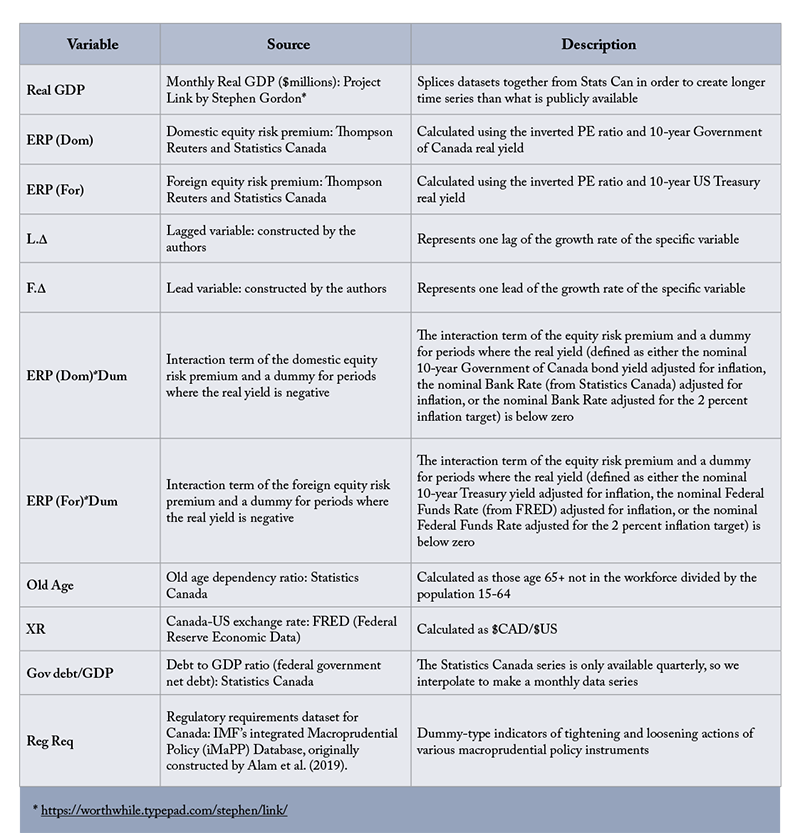

We adopt two empirical approaches to address these questions, which we refer to as Stage 1 and Stage 2 estimations. In our Stage 1 estimation, we test whether the safe asset shortage had a negative impact on the real Canadian economy when real interest rates fell below zero over the past few decades. In our Stage 2 estimation, we explore alternative explanations for this shortage. In other words, we ask what was driving this safe asset shortage? Both approaches use dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) methodology, which involves estimating econometric specifications that deal with endogeneity and unit-root (non-stationarity) concerns using leads and lags of our independent variables.

In our Stage 1 estimation, we focus on the following question: Did a safe asset shortage in Canada over the period from March 1990 to either February 2020 before the pandemic began or December 2020, the last data point where there is availability for all our data, have a negative impact on the real Canadian economy?

We define safe asset shortage periods in different ways. First, as occurring when the real 10-year bond yield on Government of Canada debt is negative – our ex ante hypothesis being that the effects of the shortage start to bind when real interest rates become negative. A second definition uses a shorter-term interest rate, e.g., the nominal Bank Rate adjusted for inflation. Lastly, given that it is possible to have negative real interest rates with high nominal interest rates – as we are seeing today – we use the periods where the nominal Bank Rate less the Bank’s 2 percent inflation target is below 0.25 percent.

In our Stage 1 specification, we use real GDP as our dependent variable. Meanwhile, the independent variable of interest is the domestic equity risk premium discussed above.

Once we have established that the effect of a safe asset shortage when real interest rates are at or below zero is detrimental for real GDP, we turn to our Stage 2 estimation that focuses on what factors are responsible for the shortage in the first place. Insights gained by answering this question enable us to discuss policies to address the shortage, which we turn to in Section 6.

In the Stage 2 specification, our dependent variable is the domestic equity risk premium. Our independent variables of interest are the five shortage explanations discussed above: the supply of government debt relative to the size of the economy, demographics, the exchange rate effect, regulatory requirements and the foreign equity risk premium (proxied by the US premium).

5. Empirical Results

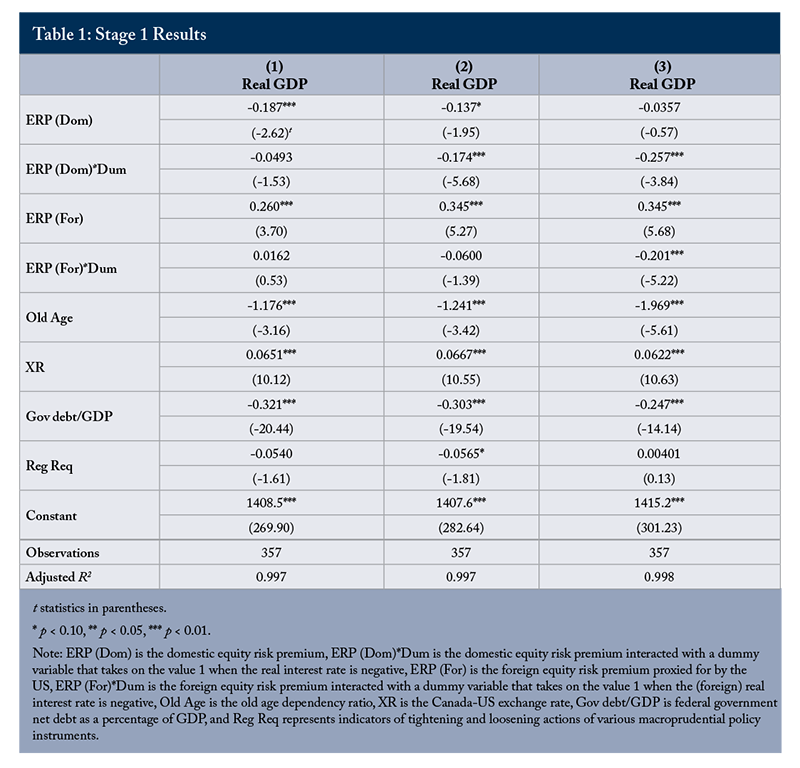

Our Stage 1 estimation results are summarized in Table 1 where our focus is the February 2020 pre-pandemic end date (the full table with sensitivity analysis, including a December 2020 end date, can be found in Appendix C). Column 1 shows the results using the real 10-year bond yield, Column 2 displays the estimation results using the real Bank Rate, while Column 3 focuses on the nominal Bank Rate adjusted for the inflation target. In all instances, we are looking at the contemporaneous effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable.

Our key Stage 1 estimation result is as follows. As expected, a widening of the domestic equity risk premium has a negative impact on real GDP (Table 1, row 1), and, critically, this impact worsens when the real interest rate, regardless of definition, reaches zero (row 2, though with some statistical insignificance with the 10-year nominal rate).

Next, a widening in the foreign equity risk premium is statistically significant, having a positive impact on real GDP (row 3).

Given the fact that the drivers of the safe asset shortage likely impact real GDP as well, we include them as control variables. An aging population, unsurprisingly, has a negative impact on real GDP. The coefficient on the exchange rate is positive and significant, likely reflecting the positive effect of a weaker Canadian dollar on exports and, hence, on GDP.

Debt-to-GDP has a negative and significant impact on real GDP, supporting the crowding-out argument. And, lastly, despite a mostly negative coefficient signalling tighter regulation weakening real GDP, the results are at best weakly statistically significant.

Overall, the key takeaway from the Stage 1 estimation is that a widening domestic equity risk premium, when the real interest rate is below zero, does appear to have a detrimental effect on real GDP.

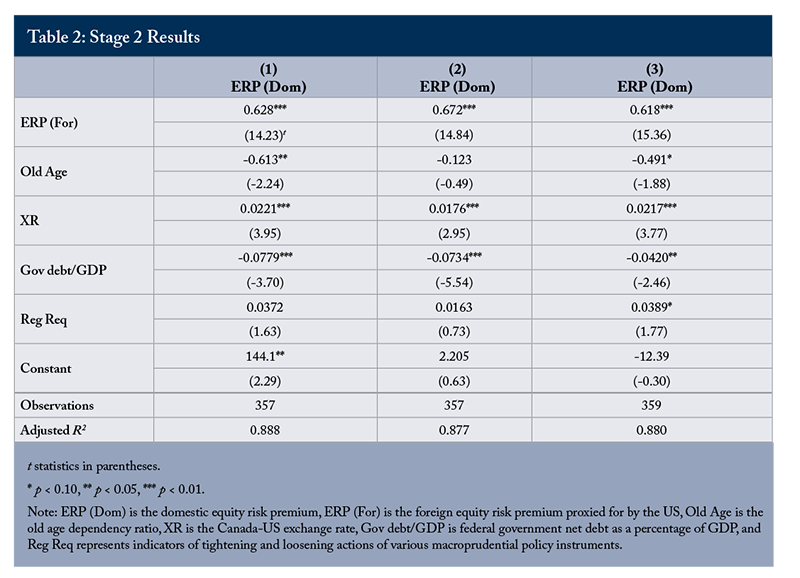

Table 2 displays summary results from our Stage 2 specification ending in February 2020 (equation 2 in Appendix A). Full results, including the December 2020 end-date results can be found in Appendix C.

We estimated three different versions of this specification, with all five possible shortage explanations included as right-hand side variables in each case. Relative to the estimation results for equation 2 in column 1 (Table 2), the results in column 2 are from a specification without real GDP (contemporaneous, leads and lags) in order to isolate the impact of the shortage explanations. The specification in the last column is the one without all the leads and lags of the variables capturing the different asset shortage explanations.

A key set of results emerge:

- As the foreign equity premium widens, so does the domestic equity risk premium;

- An aging population has weak significance, although, oddly, it shrinks the domestic equity risk premium.

It has no significance when we extend the sample end date to December 2020 (Columns 4-6 in Table C2 in Appendix C). One explanation is that the significant aging of the Canadian population begins in earnest only after 2010, so the correlation of old age and the equity risk premium might be weak in the first 20 years of the sample;We tested an interaction term of a dummy that gets a value of one from 2010 on and the old-age term, and while the sign is positive, as expected, it is insignificant. - A depreciation in the Canadian dollar leads to a widening in the domestic risk premium, as expected (as XR – the Canada-US exchange rate – increases, the currency depreciates, leading to more demand for Canadian safe assets);

- An increase in the supply of Canadian government debt leads to a narrowing of the domestic equity risk premium, as expected; and

- The coefficient on the regulatory requirements variable has almost no statistical significance, although, as expected where there is some, it widens the equity risk premium.

6. Policy Implications

Three key policy implications emerge when combining our Stage 1 and Stage 2 estimations.

First, it is not viable to increase the supply of Canadian safe assets by increasing Canadian government debt so that it would meet the excess demand for those assets. Although it might help to reduce the shortage of Canadian safe assets in the short-run, it can come at the expense of Canadian output, particularly when the government debt-to-GDP ratio is high. Moreover, if pushed too far, it can lead to a fiscal and debt crisis, as Canada experienced in the mid-1990s. The fiscal consolidation that followed was both necessary and very painful.

Second, loosening domestic regulatory requirements is unlikely to alleviate the shortage of Canadian safe assets. Furthermore, it will likely have no effect at all on the global shortage of safe assets. This is because Canada is a small, open advanced economy, and any action that we take in this regard, if it is to be consequential, must be done in concert with our peers on the international stage. Moreover, as a member of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Basel Committee on Bank Supervision, Canada has agreed to adopt international standards for the regulation of financial institutions. Unilaterally changing these regulations (or failing to follow them) would be irresponsible and counter-productive, particularly since Canada has played an important role in setting these international standards in the first place.

As discussed earlier, after the GFC, international standards for the regulation of financial institutions were significantly tightened. It is possible that they were tightened too much and that the impact on the global supply of safe assets was not fully appreciated at the time. If so, Canadian policymakers are well positioned to push for change on the international stage, given that we are an important BIS member.

Finally, if Canada wants to address domestic safe asset shortages, it needs to work with other economically significant economies in fora such as the G7, the G20 and the BIS to address the global safe asset shortage. And Canada must do this in tandem not only with other advanced economies, but also with large emerging markets on the demand side. Both the large demanders and large suppliers of safe assets must work together in order to address this global safe asset shortage.

7. Conclusions

Building on the work of Caballero, Farhi and Gourinchas (2017b), we asked and answered two key questions. First, does a safe asset shortage in a small open economy like Canada’s negatively impact real GDP? And second, which factors drive such a safe asset shortage?

Our results suggest that a domestic safe asset shortage in a country like Canada can negatively impact real GDP. In terms of drivers of the shortage, the dominant factor is the global asset shortage itself. In order to address this global problem, Canada needs to work with other economically significant economies in fora such as the G7, the G20 and the BIS. Working with others, Canada can play an important role on the international stage to help address this global problem.

Appendix A: Empirical Specifications

The first question we set out to answer is whether a safe asset shortage has a negative impact on the real economy as real interest rates reach zero. To answer this question, we estimate the following specification using dynamic OLS regression to deal with endogeneity and unit root concerns:

where rGDP is real GDP, ERP_Dom is the domestic equity risk premium; ERP_For is the foreign equity risk premium (proxied by the US) and is intended to account for the fact that both the domestic and foreign equity risk premiums matter in a small open economy; m, n and s are leads and lags of the one-period change in our independent variables; and Controls vary with our sensitivity analysis but include anything that might be correlated with both our independent variables and real GDP such as the shortage explanation variables like the old-age ratio, the Canada/US exchange rate, the supply of debt relative to the size of the economy and regulatory requirements. We put in a time trend, t, to account specifically for the trend in real GDP. The Δ represents a month-over-month change.

As noted in the main text, we include interaction terms between both the domestic and foreign equity risk premiums and a dummy variable that takes on the value of one when the real yield (defined in Canada as the nominal yield on the 10-year Government of Canada bond adjusted for inflation, the Bank Rate adjusted for inflation or the Bank Rate adjusted for the inflation target, and in the US as the 10-year real US Treasury yield adjusted for inflation, the Federal Funds Rate adjusted for inflation or the Federal Funds Rate adjusted for the inflation target) is below zero, and zero otherwise. These variables are represented as ERP_Dom*DumDom and ERP_For*DumFor respectively. We include these interaction terms due to the fact that the relationship between the equity risk premium and the economy changes as real market interest rates hit zero. Our prior is that these interaction terms will have a negative coefficient at zero.

In the second stage, the question we ask is what is responsible for the shortage in the first place.

We again run a dynamic OLS regression. Our dependent variable is the domestic equity risk premium, and our variables of interest are the five shortage explanations – supply of government debt relative to the economy (DebtGDP), demographics (Demog), the exchange rate effect (XR), regulatory requirements (RegReq), and the foreign equity risk premium (ERPFor, proxied by the US). Again, we add in a time trend, t, to deal with the trend found in real GDP (rGDP), which we include as a right-hand side variable as well. The Δ represents a month-over-month change.

The regression specification is as follows:

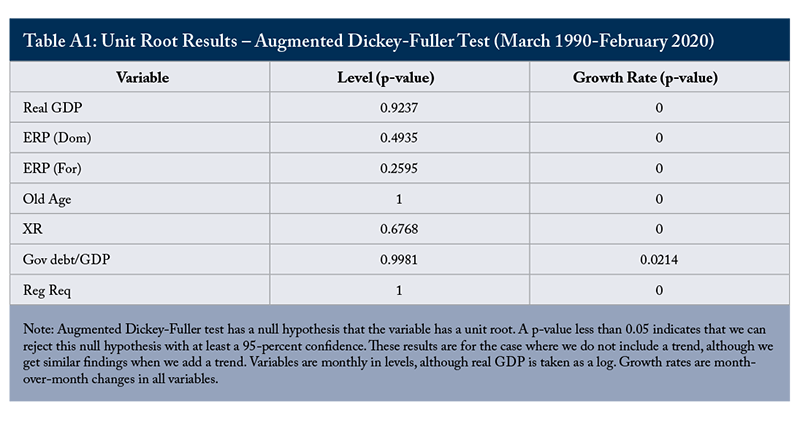

The unit root tests can be found in Table A1. All variables are integrated of order 1. As there is co-integration among the variables in our specification, we can run the regressions in levels where, as mentioned, we account for the trend in real GDP with a time-trend variable.

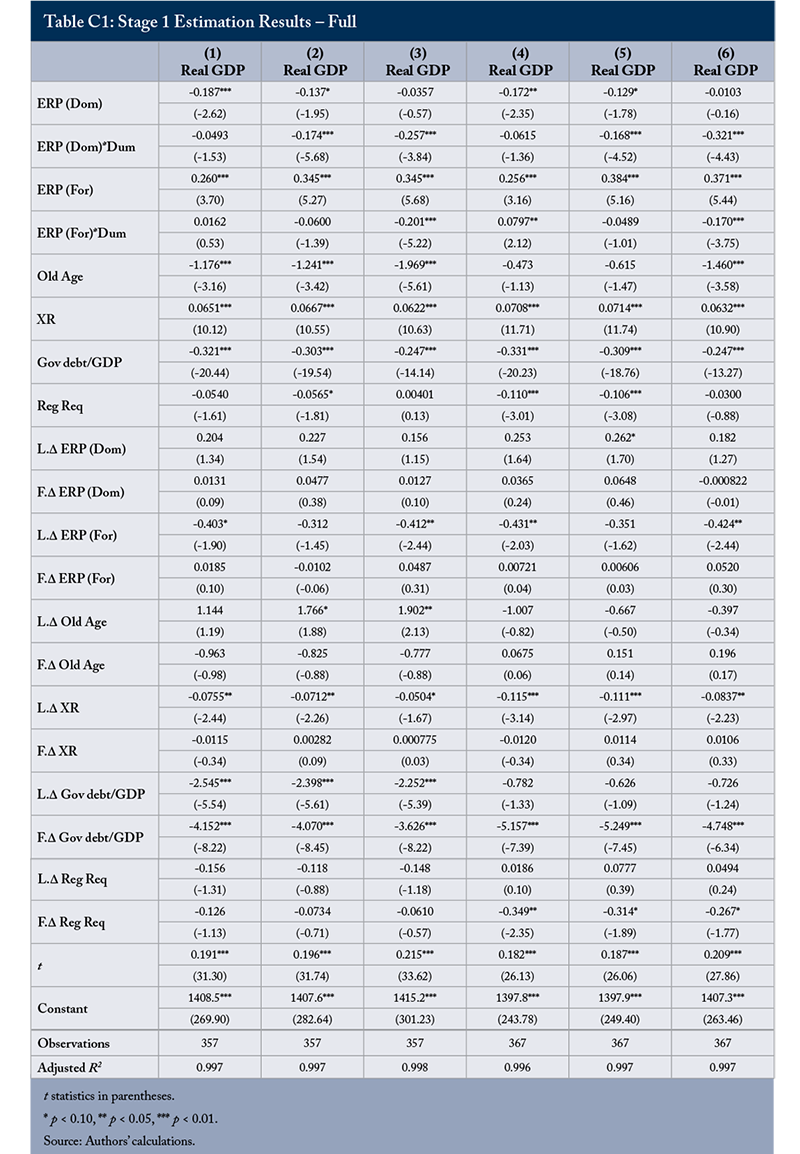

Appendix B: Data Description and Sources

Sample period: March 1990 to December 2020. The end date reflects the end of the sample period in the regulatory requirement dataset.

Appendix C: Full Estimation Results

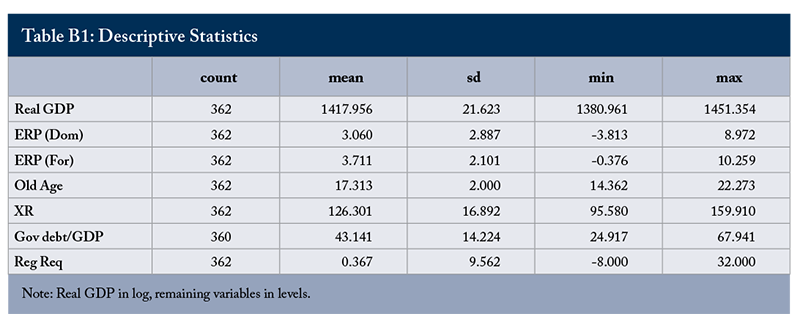

Table C1 shows the full set of results described in section 5.1.

The first three columns are the same specifications as in Table 1 in the main text but also include the results of the leads, lags and time trend. As a robustness check, we estimated equation 1 up until December 2020, with the results shown in columns 4-6. The critical finding of a negative and significant coefficient on the domestic equity-risk premium interaction term (row 2) continues to hold under this robustness check. The other, more secondary, results on the shortage explanations mostly continue to hold as well.

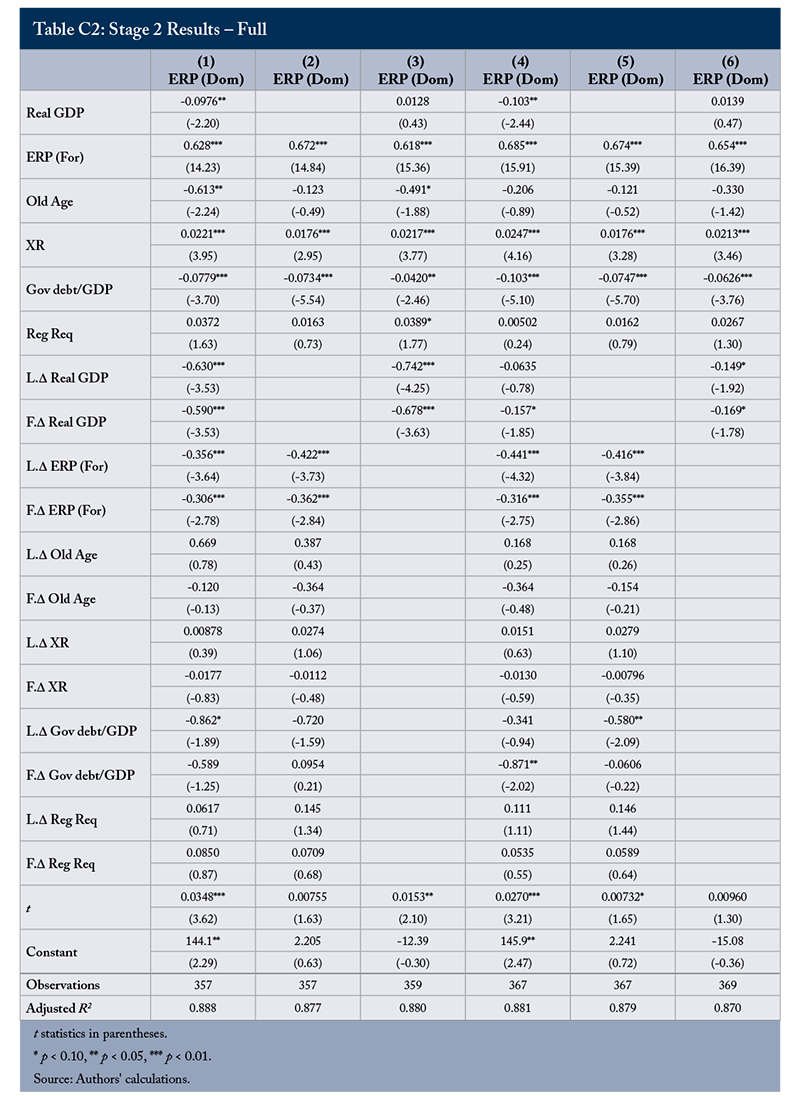

Table C2, columns 1-3, shows the full set of results described in section 5.2. Columns 4-6 run the same exercise for a December 2020 end-date. Results remain consistent, including the dominance of the foreign equity risk premium in its impact on the domestic equity risk premium.

References

Acharya, S., and K. Dogra. 2020. “The Side Effects of Safe Asset Creation.” Staff Working Paper 2021-34. Bank of Canada.

Alam, Z., et al. 2019. “Digging Deeper – Evidence on the Effects of Macroprudential Policies from a New Database.” IMF Working Paper No. 19/66.

Almadani, S., et al. 2020. “The Stability of Safe Asset Production.” FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Bernanke, B. 2005. “The Global Saving Glut and the US Current Account Deficit.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US).

Caballero, R., E. Farhi, and P. Gourinchas. 2016. “Safe Asset Scarcity and Aggregate Demand.” American Economic Review 106 (5): 513–18. May.

———. 2017a. “The Safe Asset Shortage, the Rise of Mark-Ups, and the Decline in the Labour Share.” CEPR Vox Column. December 13.

———. 2017b. “The Safe Assets Shortage Conundrum.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. 31 (3): 29–46. Summer.

Davies, G. 2020. “The safe asset shortage after Covid-19.” Financial Times, June 28.

Eichenbaum, M. 2021. “Should We Worry About Deficits When Interest Rates Are So Low?” C.D. Howe Institute Jack Mintz Lecture. September 10.

Ferreira, T., and S. Shousha. 2020. “Scarcity of Safe Assets and Global Neutral Interest Rates.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. International Finance Discussion Papers. Number 1293. July.

Habib, M., L. Stracca, and F. Vendittie. 2020. “The Fundamentals of Safe Assets.” European Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 2355. January.

Gorton, Gary, Stefan Lewellen, and Andrew Metrick. 2012. “The Safe-Asset Share.” American Economic Review 102 (3): 101–06. May.

Gourinchas, P., and O. Jeanne. 2012. “Global Safe Assets” BIS Working Paper no. 399.

Imam, P. 2013. “Shock from Graying: Is the Demographic Shift Weakening Monetary Policy Effectiveness.” IMF Working Paper. WP/13/191.

Jordà, Ò., M. Schularick, and A. Taylor. 2016. “Sovereigns Versus Banks: Credit, Crises, and Consequences.” Journal of the European Economic Association. 14 (1): 45–79. February.

Kim, S. 2020. “The Nexus of Safe Asset Shortage, Credit Growth, and Financial Instability.” ADBI Working Paper no. 1163.

Krishnamurthy, A., and A. Vissing-Jorgensen. 2015. “The Impact of Treasury Supply on Financial Sector Lending and Stability.” Journal of Financial Economics. 118 (3): 571–600. August.

Reinhart, C., V. Reinhart, and K. Rogoff. 2012. “Public Debt Overhangs: Advanced-Economy Episodes Since 1800.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. 26 (3): 69–86. Summer.

Schuknecht, L. 2018. “The Supply of Safe Assets and Fiscal Policy.” Intereconomics. 53 (2): 94–100. March.

Schumaker, Malte D., and Dawid Zochowski. 2017. “The Risk Premium Channel and Long-Term Growth.” European Central Bank Working Paper No 2114. December.

Stein, Jeremy C. 2012. “Monetary Policy as Financial Stability Regulation.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 127 (1): 57–95. February.

Stock, James H., and Mark W Watson. 1993. “A Simple Estimator of Cointegrating Vectors in Higher Order Integrated Systems.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society. 783–820. July.

Summers, L. 2016. “The Age of Secular Stagnation: What It Is and What to Do About It.” Foreign Affairs. Foreign Affairs. March/April 2016.

Zhang, Yang, et al. 2021. “Sequencing Extended Monetary Policies at the Effective Lower Bound.” Staff Discussion Paper 2021-10. Bank