The Study in Brief

-

The federal government’s expenditure management system (EMS) has many desirable characteristics but needs substantial reform to achieve its objectives of ensuring that programs are effective, efficiently delivered, aligned with government priorities, and represent value for money.

-

Evaluation of government transfer payments is the cornerstone of the EMS, but its impact is diminished by: Excluding measures delivered through the tax system, which are about a quarter the size of total transfer payments; and focusing effectiveness assessments on the responses of program beneficiaries instead of value for money.

-

If evaluations are to influence spending decisions, value-for-money assessments – supplemented with information on the distributional impact of policies – must be mandatory, not optional.

-

Spending proposals should be subject to a simplified value-for-money assessment, and the results made public, as is now required for regulatory proposals and environmental initiatives with a substantial environmental impact.

Spending proposals should be subject to a simplified value-for-money assessment, and the results made public, as is now required for regulatory proposals and environmental initiatives with a substantial environmental impact. -

A revamped EMS should include a multi-year ceiling on spending. The expenditure ceiling would be set out in the first budget of a new government and would be binding over its mandate. It would cover non-cyclical spending and include a policy reserve.

A revamped EMS should include a multi-year ceiling on spending. The expenditure ceiling would be set out in the first budget of a new government and would be binding over its mandate. It would cover non-cyclical spending and include a policy reserve.

The author thanks Alexandre Laurin, Daniel Schwanen, Jeremy Kronick, Don Drummond, Evert Lindquist, Trevor Tombe and anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier draft. The author retains responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

Introduction

A 2023 C.D. Howe Institute E-Brief, Canada Needs a New Fiscal Strategy, developed the idea that better fiscal outcomes would be achieved if governments surrender some policy flexibility. To overcome its bias in favour of deficit financing in good times and bad, Ottawa should adopt guiding principles for the conduct of fiscal policy, set out operational rules for achieving target outcomes, and be transparent in monitoring action against these principles and rules.

This paper discusses reforms to the government’s expenditure management system (EMS) to complement such a new fiscal governance framework. Adopting the proposed governance strategy and revamping the government’s EMS would result in sounder public finances. It would lessen the bias in favour of debt financing and would yield better value for money in federal spending.

The Federal Government’s Expenditure Management System

An effective EMS should “ensure that all programs are focused on results, provide value for taxpayers' money and are aligned with the government’s priorities and responsibilities”(Treasury Board Secretariat 2015). It has three components: assessment of policy proposals, measuring and evaluating program performance, and transmitting salient information on spending and program performance to parliamentarians and the public. The following section will discuss these components starting with measuring performance because proposal assessment makes use of the performance measurement and evaluation framework.

Performance Measurement and Evaluation

The government’s Policy on Results and the accompanying Directive set out performance measurement and evaluation requirements for departmental programs and “organizational spending.” The policy thus covers all departmental spending: transfer payments, internal services, and all other initiatives undertaken by departmental personnel, such as services provided directly to the public and policies administered by departments.1

The Directive on Results provides a framework for performance measurement and evaluation, leaving departments considerable flexibility in how to implement the policy. Departments must formulate expected program outcomes and publish reports annually on progress in achieving these outcomes. The reports should show a logical progression of key impacts over time and make clear the causal relationships involved. For transfer payments, outcomes are formulated in terms of how recipients respond to the program (immediate and intermediate outcomes) and the broader benefits of these responses (long-term or ultimate outcomes). For example, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada’s performance measurement of the Innovation Superclusters Initiative sets out the expectation that subsidy recipients will invest in R&D and commercialization, making Canada more competitive and productive, thereby contributing to economic growth.

Evaluations should address relevance, efficiency, and effectiveness, when appropriate given the goals of the evaluation. The assessment of relevance determines if the program addresses a demonstrable need, reflects existing government priorities, and is a federal responsibility. Efficiency is assessed in terms of program delivery costs. The effectiveness assessment determines if the program achieves its expected outcomes. Various types of evaluations are permitted under the policy. Among other issues, evaluations may focus on design and delivery, on the response of program beneficiaries, or on a comparison of the costs and benefits of a program.

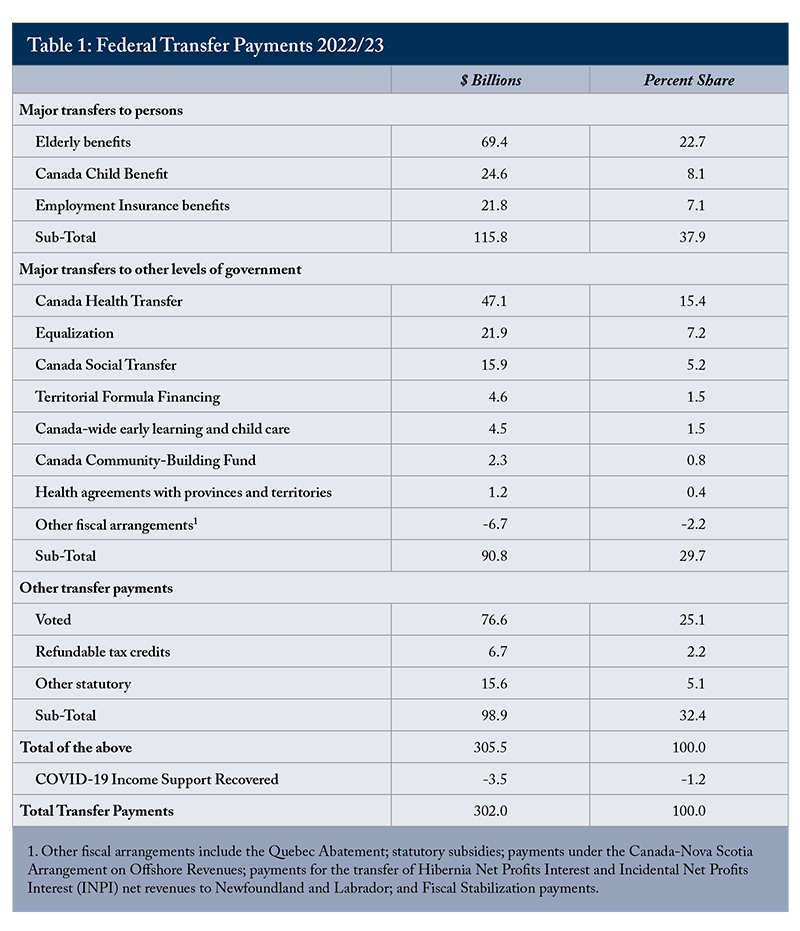

Evaluation requirements are more stringent for grant and contribution (G&C) programs that must be approved by Parliament (voted) annually than for other spending. Voted G&C programs with a budget of more than $5 million must be evaluated once every five years and the results made public.2 In addition, evaluations of these programs must address relevance, efficiency, and effectiveness. In contrast, other programs and organizational spending are to be evaluated “periodically” at the discretion of departments, and there is no requirement to publish the results. G&C programs voted by Parliament amounted to $77 billion in 2022/23, or about a quarter of total transfer payments (Table 1).

Departments are required to prepare annual five-year evaluation plans. In addition to listing scheduled evaluations, the plan must identify the extent of organizational spending and programs that will not be evaluated, provide a justification for such a decision, and state when they were last evaluated.

The Policy on Results also stipulates that departments may be subject to a Resource Alignment Review (RAR) initiated by the president of the Treasury Board, potentially affecting both statutory and voted transfer payments. RARs are implemented to ensure programs are effective and aligned with government priorities. An assessment of information technology used at Shared Services Canada undertaken in 2017 is the most recent RAR available.

Another element of performance measurement and evaluation is periodic centralized review of programs. In the first three years of its mandate, the current government undertook comprehensive reviews of five departments with the intention of reallocating spending to reflect more closely existing government priorities. The government also undertook “horizontal” reviews of spending on professional services, travel, advertising, and innovation and clean technology programs during this period. The 2022 and 2023 budgets announced a government-wide strategic policy review, labelled Refocusing Government Spending, that involves spending reductions as well as reallocations of spending.

The Parliamentary process for approving spending is also part of the EMS. The details of planned spending are tabled in the House of Commons in the Estimates no later than March 1 each year.3 Once tabled in the House of Commons, the Estimates are referred to separate Parliamentary committees to review voted spending.

These committees have broad powers to examine spending, including the right to reduce or reject voted estimates before reporting on them to the House, and to question ministers and public servants (Auditor General of Canada 2015). A key committee in this is the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates, created in 2002 and chaired by a member of the Opposition. This Committee has a mandate to assess the estimates process and has the authority to examine statutory programs and tax expenditures.4 In 2012, the Committee expressed concern that “standing committees are at best giving perfunctory attention to the government’s spending plans”5 and in 2019 concluded that “the estimates process lacks meaningful scrutiny.”6 The Committee has not yet exercised its authority to examine statutory programs and tax expenditures.

Since 2017, the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) has a mandate to assess the government’s spending plan as set out in the Estimates, and to determine the financial cost of spending proposals.7 This expansion of the mandate was made to promote greater budget transparency and accountability.8 Under this mandate, recent PBO publications range from presenting the government’s expenditure plan and Estimates in a more comprehensive and readable format to estimating the fiscal cost of the Investment Tax Credit for Clean Hydrogen and an analysis of the Defense Department’s capital spending over a 20-year horizon. PBO reports facilitate program performance measurement and evaluation by increasing the evidence base.

Policy proposals are approved in at least two steps. First, detailed proposals are submitted to Finance Canada for vetting and approval for funding by the minister of finance and the prime minister. Second, implementation is authorized by the Treasury Board. A possible additional step is prior approval by a Cabinet policy committee. Finance Canada has prepared detailed guidance for submitting proposals for new initiatives, renewing sunsetting initiatives, and changing existing initiatives. Among other things, proposals must contain a detailed policy rationale, an assessment of alternative delivery options, a discussion of expected impacts, and must specify indicators by which the effectiveness of the initiative will be assessed.

The policy rationale covers relevance as defined above, but submissions must also explain how the proposal responds to the policy need that has been identified and why new funding is required, instead of funding through internal reallocations or cost recovery.

The requirements for the analysis of expected outcomes deviate from the performance measurement framework discussed above. Submissions must discuss how proposals affect the quality of life indicators first presented in Budget 2021, making it easier to assess the relative impacts of proposals. Proposals must identify expected beneficiaries of the initiative by gender, age, and income. Expected regional and sectoral impacts must also be discussed, if relevant. Claims about expected impacts should be supported by impact modelling results, evaluations of similar initiatives, and academic research.

All proposals with significant positive or negative environmental impacts must include a Strategic Environmental and Economic Assessment. The standardized template for the assessment requires detailed information on environmental impacts, including quantitative estimates of the net impacts on green house gas emissions. A quantitative economic assessment must be prepared by Finance Canada for proposals that involve spending of at least $150 million per year. Key outputs of the economic assessment are the incremental impacts on employment, the cost per job created, and the increase in GDP per dollar of program cost. A public statement on the assessment must be issued.

After approval by the finance minister and the prime minister, the proposal must be submitted to the Treasury Board to authorise implementation. According to the Treasury Board Guidance, submissions must present the plan to carry out initiatives, discuss the expected results, and review the associated risks. The submission must demonstrate that the design and delivery model has considered evaluations of similar initiatives, that it will be effective and efficient, and that it will provide best value for money. The discussion of expected results must use the performance measurement framework for existing programs. The submission must also state the expected timing and scope of evaluations of the initiative.

The second component of an effective EMS is transmitting useful information on spending and program performance to parliamentarians and the public. The main elements here are the publication of five-year spending plans for major spending categories in the annual budget and the Main Estimates Publication, along with related supplementary information provided on the Treasury Board website. PBO reports also contribute substantially to fiscal transparency.

Part I of the Main Estimates Publication presents the government’s overall expenditure plan and a detailed listing of planned expenditures by type and purpose. The 2024/25 edition presents the interim results of the government’s exercise on Refocusing Government Spending. Part II of the document presents detailed information by department.

Departments must prepare reports on their spending plans (Departmental Plans) and table them before Parliament shortly after the Estimates. They must also table reports on spending outcomes (Departmental Results Reports, or DRRs) in the fall for the fiscal year ended in March. These two reports, which are considered Part III of the Estimates, present detailed, multi-year information on spending. The DRRs compare actual performance of program suites with plans and expected results set out in the Departmental Plans. Department Plans and DRRs are posted on departmental websites along with various supplementary information. The supplementary information on transfer payments is particularly useful. It provides a description of the purpose and objectives of the program, targeted recipients, expected results, and spending by type of transfer payment.

Shortcomings of the Government’s Expenditure Management System

The federal EMS looks very good on paper. Policy proposals are assessed by central agencies, departments set performance criteria for their programs, measure outcomes against these criteria, and undertake formal evaluations of most programs. There are periodic centralized reviews of spending, and the government provides an abundance of information to parliamentarians and the public. A closer look, however, reveals some important flaws and gaps.

Incomplete Coverage of Spending

The first flaw is incomplete coverage of spending. Spending programs authorized through the Income Tax Act are not subject to the performance measurement and evaluation requirements, although they have been included in government spending since 2012. These programs comprise the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), which cost $24 billion in 2022/23, and refundable tax credits, which amounted to $6.7 billion (Table 1). As a result, about 10 percent of the transfer payments reported in Table 1 are not subject to the performance measurement and evaluation requirements.

Further, there is a solid case for including non-refundable tax credits and other tax preferences in the performance measurement and evaluation regime. There is no substantive difference between, for example, a spending program that subsidizes business investment and a tax credit provided for the same purpose. Estimates of the tax revenue forgone through tax preferences are presented in the Report on Federal Tax Expenditures, published by Finance Canada. Tax expenditures reported in the document include measures implemented to improve the fairness and efficiency of the tax system as well as measures implemented to achieve an economic or social objective. I estimate that measures with an economic or social objective, which I describe as tax-based spending programs, will cost about $45 billion in 2022 – 15 percent of total transfer payments shown in Table 1.9

Ensuring that tax expenditures are included in the purview of the Policy on Results would be less of a concern if Finance Canada were conforming to the Policy voluntarily. While Finance Canada does undertake evaluations of tax expenditures, only three have been published since 2020.10

Evaluation Requirements Are Unbalanced

The requirement that ongoing voted grant and contribution programs be evaluated every five years for relevance, efficiency, and effectiveness is excessive, while not requiring evaluation plans and results for other spending to be published is a substantial shortcoming.

Flexibility in the timing and frequency of evaluations is good public policy. So is flexibility in the type of evaluation performed. The frequency, timing, and type of evaluation performed should be determined by the organization’s need for information (Bourgeois and Whynot 2018). If ongoing monitoring suggests there is less need for a program, if efficiency is an issue, or if expected outcomes are not being achieved, an evaluation should be performed. The evaluation could focus on relevance, operational efficiency, or effectiveness as appropriate. Repealing the special requirements for ongoing voted grant and contribution programs would reduce costs without compromising the objectives of the performance management and evaluation system.

On the other hand, all evaluations should be published. It does not serve the public interest to forgo disclosure of evaluations of major transfer programs such as the Canada Child Benefit and Equalization.11 There may be sound reasons for delaying evaluations and these reasons must be disclosed in departmental evaluation plans, but there is no requirement to publish these plans.12

Value for Money Gets Short Shrift

Spending programs should have to pass a public interest test to ensure that taxpayers are getting value for money. Unfortunately, value for money is at best indirectly addressed at the proposal stage and is an optional concern at the performance evaluation stage.

Treasury Board Secretariat guidance on submitting proposals for approval considers value for money only in the context of operational efficiency. Finance Canada guidance requires a short qualitative assessment of how proposed programs will affect quality of life indicators and other indicators where appropriate. However, this information is inadequate to make an informed judgement on whether the program is likely to pass a public interest test, because the benefits are assessed qualitatively and costs are not considered.

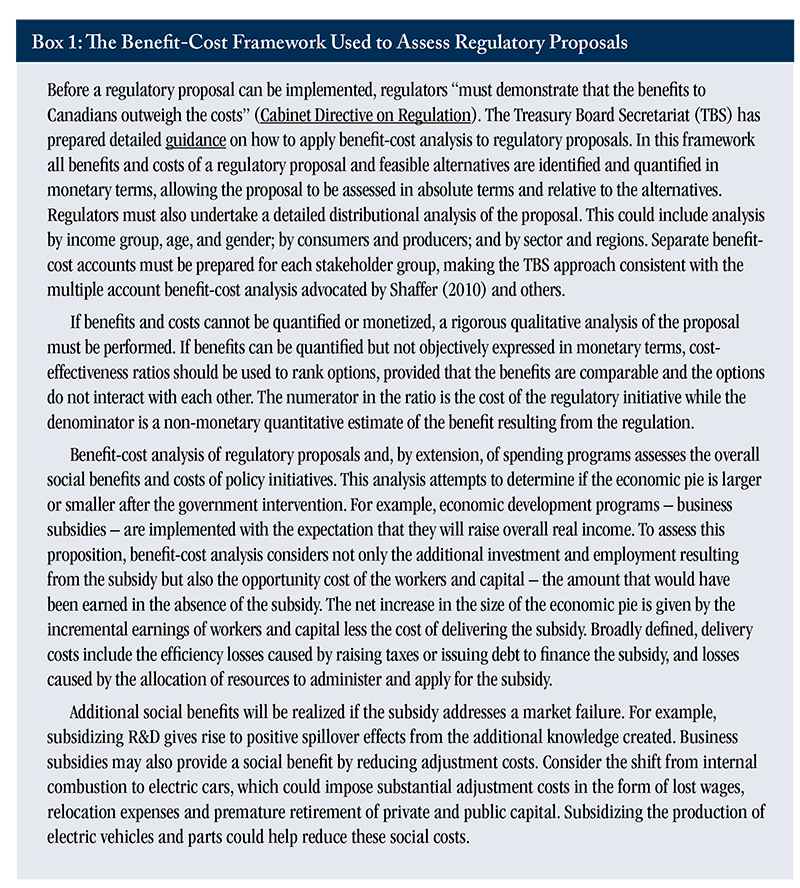

Proposals triggering a Strategic Environmental and Economic Assessment are screened more thoroughly, but value for money is still not adequately addressed. The environmental benefits or costs are quantitatively assessed, as are the economic impacts. However, the economic assessment does not cover all the social costs and benefits required for a value-for-money assessment, as described in Box 1.

On the other hand, the need to explain why new funding is required, instead of funding through internal reallocations, opens the door to value-for-money assessments. In addition, spending departments and Finance Canada have the option of undertaking more analysis of program proposals than required in the guidance. Despite these possibilities, the analysis of battery plant subsidies made public does not inspire confidence that value for money is being rigorously assessed. The $13 billion subsidy for Volkswagen was justified by claiming that it would pay for itself over five years through tax revenues generated directly and indirectly by the project. The calculation is flawed because it assumes all the activity induced by the subsidy will be incremental, ignoring the fact that plant workers will be employed elsewhere absent the subsidy. More importantly, even the best pay-back calculation is not a reasonable basis for making a decision. Carefully assessed, business subsidies will always have a net fiscal cost, but that does not preclude them from passing a public interest test.

The Policy on Results states that evaluations should “judge merit, worth or value” but does not require that programs be assessed against these criteria. A review of 48 evaluations prepared since 2020 in eight departments13 found that only four went beyond assessing impacts on program beneficiaries to examine whether the program represented value for taxpayer money. Three of these evaluations applied a formal benefit-cost analysis, which is the standard for assessing regulatory proposals.14

The Policy on Results should be changed to make value-for-money assessment mandatory except for organizational spending. Value-for-money assessments should be based on the benefit-cost framework applied to assess regulatory proposals (Box 1). The nature of the assessment would vary by the type of program. Business subsidies, labour market development programs, and climate change mitigation/adaptation measures have benefits and costs that can be measured in monetary terms. These programs could be ranked by their net social benefits, allowing comparisons within peer programs and to a lesser extent across program categories. Programs for which benefits are less than costs would be considered for elimination or modification, independent of their ranking.

The benefit-cost framework could be applied to programs having a fairness objective if there were a consensus on their economic impacts, but there is not. The extensive empirical research on the economic benefits of greater income equality is inconclusive: the impact could be positive or negative (Baselgia and Foellmi 2022). Reliable estimates of their economic impact, whether positive or negative, would allow programs to be ranked by their net benefits, although it is worth emphasizing that a negative net benefit would not be sufficient reason to consider eliminating a fairness initiative.

In the absence of reliable estimates of their economic benefits, a variant of the cost-effectiveness ratios discussed in Box 1 are a more useful evaluation metric for fairness programs. The numerator of this ratio would be some measure of the amount of income redistribution achieved and the denominator would be the fiscal cost of the measure. The income redistribution measure could be an indicator of the change in the overall distribution of income such as the Gini coefficient, or a measure based on a comparison of top or bottom incomes with average incomes. Using this ratio to rank programs implicitly assumes that the gross social benefits of a given amount of income redistribution do not change across programs and that the gross social cost of the measure is proportional to its fiscal cost. Neither of these assumptions are likely to be true but will be less problematic for programs with similar characteristics.

Spending proposals should be screened using a simplified version of the benefit-cost framework. Consistent with the treatment of regulatory proposals, the effort spent on these assessments and evaluations should be proportionate to their expected impact. Assessments of regulatory and spending proposals with significant environmental impact must be made public; other spending proposals should be subject to the same requirement.

Disinterest in evaluations by policymakers is a longstanding issue. Dobell and Zussman (1981, 407) state that the system “failed to consider the … information needs of the user.” The Ministerial Task Force on Program Review (the Nielsen Task Force) operating from 1984 to 1986 described evaluations as “generally useless and inadequate for the work of program review” (Quoted in Grady and Phidd 1993). The situation has not changed in the intervening years. McDavid et al. (2018, 302) conclude that evaluations do not “address questions that would be asked as cabinet decision-makers choose among programs and policies.” When combined with data on the distributional impacts of policies, value-for-money assessments would make evaluations useful for decision-makers and the public. Specifically, this information would facilitate the institutionalized spending reviews advocated by Lindquist and Shepherd (2024).

There are, however, other issues to consider when assessing whether evaluations can contribute effectively to spending reviews. Mayne (2018) argues persuasively that evaluations must be performed by a central agency. A basic point is that it is not reasonable to expect departmental evaluators to question the existence of programs that have been endorsed by their minister. In addition, centralizing relevance and value-for-money assessments would allow horizontal issues to be addressed and the timing and content of evaluations to be more closely integrated with the needs of decision-makers. The PBO’s mandate is consistent with performing this function, but if the Treasury Board Secretariat performed the relevance and effectiveness evaluations, it would be better able to ensure evaluations meet the needs of policymakers.

No Constraint on Aggregate Spending

Another important gap is the absence of any constraint on aggregate spending. While five-year spending plans are announced each year in the budget, they are not binding. Since the pandemic, program spending has been increased in successive budgets and economic and fiscal updates, such that program spending as a share of GDP in 2024/25 will be almost 2 percentage points higher than projected in the 2019 Economic and Fiscal Update.15 Without a self-imposed constraint, performance evaluation loses much of its punch: there is no need to set priorities and weed out underperforming programs.

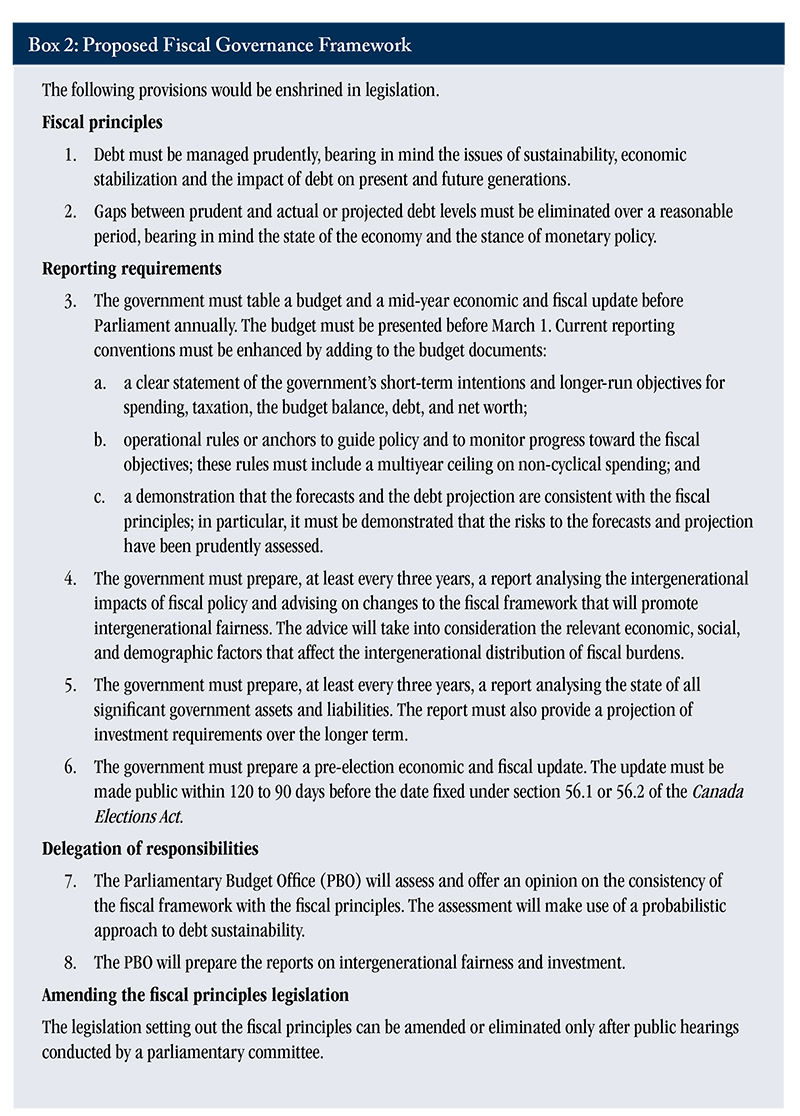

Binding multi-year expenditure ceilings apply in 12 OECD member countries (Moretti, Keller, and Majercak 2023).16 In some of these countries – the Netherlands and Switzerland – the ceilings are set out in legislation that constrains expenditure growth. Alberta has recently adopted the same approach.17 However, in most countries expenditure ceilings are set by the government to ensure consistency with its self-defined fiscal objectives, which may or may not include expenditure restraint. Lester and Laurin (2023) recommend this approach for Canada as part of a proposed new fiscal governance framework, summarized in Box 2. The proposed expenditure ceiling is not meant to impose a view on the size of the government. Its intention is to force governments to set out clearly their views on the upper limit of program spending over their mandate.

The expenditure ceiling would be developed in the first year of a new electoral mandate. It would cover all categories of spending directly affected by policy decisions. All program spending excluding cyclically sensitive spending,18 and several other smaller spending categories such as non-wage operating costs,19 would be included in the ceiling, as would transactions with enterprise Crown corporations. The Canada Carbon Rebate or any such future program would be excluded because there is a matching offsetting revenue source. The ceiling would be binding annually in the aggregate, not by component, except for multi-year, non-statutory transfer programs for which the total multi-year commitment would bind.

Forecasts of spending delivered through statutory programs would be conditional on the assumptions of how the program determinants evolve over the mandate. That is, the cap for statutory spending programs would be updated as forecasts of economic conditions and demographic projections are revised. Projected spending on voted programs would be based on announced funding in budgets and the spending profiles set out in Departmental Plans.20 Projected spending on employee compensation would be based on the forecast of full-time equivalent employees shown in Departmental Plans and a forecast of per employee compensation costs, which is implicit in the information on operating costs presented in Departmental Plans. The forecast of compensation costs would be adjusted for forecast errors, but the cost of higher-than-planned staffing levels would come out of the policy reserve, discussed below.

The expenditure ceiling would include a provision for new policy initiatives. The size of this policy reserve and how it is specified (nominal or constant dollars, percentage of controlled spending or of GDP) would be at the discretion of the government. The important point is that the government would commit to a path for non-cyclical spending over its mandate that would be subject to public scrutiny.

The expenditure ceiling would have escape clauses for major economic recessions, major natural disasters, and war. For example, faced with a severe economic downturn, the government could increase spending to support incomes. The programs would have to have an explicit end date. The resulting increase in debt would be assessed against the announced fiscal objectives (Box 2) and actions to pay down the debt would be undertaken if necessary to restore consistency with these objectives.

Compliance with the expenditure ceiling would be monitored by an independent third party, such as the PBO. The PBO would receive, on a confidential basis, the detailed government expenditure forecasts underlying spending projections in budgets and fiscal updates, along with an explanation for any changes. The PBO would verify that the changes in spending outside of the policy reserve were induced by changes in economic conditions.

The enabling legislation for the proposed fiscal governance framework, including the expenditure ceiling, could require that political parties include a five-year expenditure plan in their election platforms. This would help voters make an informed choice and give the winning party a clear mandate on its spending plans. For this to work, the government would have to include a detailed expenditure plan in the pre-election Economic and Fiscal Update, envisaged in the proposed new governance framework (Box 2). There are, however, limits to how much detail on spending can be provided without compromising, for example, contract negotiations and litigation issues, so any pre-election expenditure ceiling would have to be less comprehensive than a post-election ceiling.

Canada has used variants of top-down, multi-year expenditure budgeting since 1979 when the Policy and Expenditure Management System was introduced. The novel feature of the proposed ceiling is that, after adjustment for changes in economic circumstances, it will be binding over an electoral mandate. The level of federal spending is now jointly determined by the finance minister and the prime minister. Under the proposed ceiling, they would have to commit to a five-year spending plan.

Summary of Proposed Changes to the Federal Expenditure Management System

To become effective, the federal government’s expenditure management system needs to broaden its coverage, performance management requirements must be more flexible, value-for-money assessments of policy proposals and program performance must be mandatory, and an expenditure ceiling must be imposed.

• Expenditures authorized under the Income Tax Act – the Canada Child Benefit and refundable tax credits – should be included in the performance management framework.

• Non-refundable tax credits with an economic or social objective should also be included in the performance management framework. Specifically, Finance Canada should be required to publish an evaluation plan and conduct value-for-money assessments of these credits.

More Balanced Evaluation Requirements

• The frequency, timing, and type of evaluation performed for all programs should be determined by the results from the performance management system. Evaluating all ongoing voted programs of grants and contributions for relevance, efficiency, and effectiveness every five years is excessive.

• Evaluations of all spending, not just ongoing voted programs of grants and contributions, should be made public.

• Departments should also be required to publish their evaluation plans.

Mandatory Value-for-money Assessments

• Value-for-money assessments should be mandatory. Programs should be evaluated using the benefit-cost framework developed for assessing regulatory proposals. The framework would be modified when assessing programs with a fairness initiative.

• Spending proposals should be screened using a simplified version of the benefit-cost framework, and their assessments should be made public, as they are for regulatory proposals and environmental initiatives.

• Value-for-money assessments should be undertaken by the Treasury Board Secretariat.

• Governments should adopt a binding five-year plan for non-cyclical spending, including a policy reserve, at the beginning of their mandates.

• Cyclical spending would include established programs such as Employment Insurance and any time-limited measures implemented to support incomes during an economic downturn.

• Governments would have complete discretion in specifying a policy reserve. It could be specified in nominal or constant dollars, or as a percentage of cyclically adjusted GDP.

• The ceiling would apply annually to aggregate spending, not the components, except for multi-year non-statutory transfer programs.

• The expenditure plan would be updated annually to account for errors in forecasting the determinants of spending programs (e.g. inflation, growth in the recipient population) and to show the impact of new initiatives on the policy reserve.

Conclusion

The federal government’s expenditure management system is not achieving its goal of ensuring that programs provide value for taxpayers' money. Progress will not be made until effectiveness evaluations shift from focussing on the response of program beneficiaries to a broader analysis of social benefits and costs. A self-imposed ceiling on spending would reinforce the proposed reforms to evaluation policy by giving the government a greater incentive to set priorities and eliminate underperforming programs.

The reforms proposed in this paper would complement the recommendations made by Lester and Laurin (2023) to adopt a principles-based fiscal governance framework to address the issue of a bias in favour of deficit financing. Implementing the entire package would result in a more prudent approach to debt financing, better control over spending, and improved value for money in spending. However, implementation would follow, and reinforce, a political consensus on the need for reform. The task for public policy analysts is to help build this consensus.

References

Auditor General of Canada. 2015. “Examining Public Spending—Estimates Review: A Guide for Parliamentarians.” Available at https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/english/meth_gde_e_10218.html#hd3e.

Bourgeois, Isabelle, and Jane Whynot. 2018. “Strategic Evaluation Utilization in the Canadian Federal Government.” Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 32 (3): 327–46. Available at https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.43179.

Dobell, Rodney, and David Zussman. 1981. “An Evaluation System for Government: If Politics Is Theatre, Then Evaluation Is (Mostly) Art.” Canadian Public Administration 24 (3): 404–27. Available at https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.1981.tb00341.x.

Finance Canada. 1979. “The New Expenditure Management System.” Available at https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.829669/publication.html.

Grady, Patrick, and Richard W. Phidd. 1993. Budget Envelopes, Policy Making and Accountability. Government and Competitiveness Project, School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University. Available at http://global-economics.ca/budgetenvelopes.pdf.

Lester, John. 2012. “Managing Tax Expenditures and Government Program Spending: Proposals for Reform.” University of Calgary School of Public Policy Research Paper 5 (35). Available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2321923.

Lester, John, and Alexandre Laurin. 2023. “Ottawa Needs a New Approach to Fiscal Policy.” E-Brief 338. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4397967.

Lindquist, Evert, and Robert Shepherd. 2024. Smarter Government for Turbulent Times. Commentary 652. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4721817.

Mayne, John. 2018. “Linking Evaluation to Expenditure Reviews: Neither Realistic nor a Good Idea.” Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 32 (3): 316–26. Available at https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.43178.

McDavid, Jim, Astrid Brousselle, Robert P. Shepherd, and David Zussman. 2018. “Linking Evaluation and Spending Reviews: Challenges and Prospects.” Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 32 (3): 297–304. Available at https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.43176.

Moretti, Delphine, Anne Keller, and Marco Majercak. 2023. “Medium-Term and Top-down Budgeting in OECD Countries.” OECD Journal on Budgeting 23 (3). Available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/39425570-en.

Robson, William B.P., and Alexandre Laurin. 2017. Hidden Spending: The Fiscal Impact of Federal Tax Concessions. Commentary 469. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Shaffer, Marvin. 2010. Multiple Account Benefit-Cost Analysis: A Practical Guide for the Systematic Evaluation of Project and Policy Alternatives. University of Toronto Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=l3Vbb6e_48gC&oi=fnd&pg=PT7&….

Treasury Board Secretariat. 2015. “The Expenditure Management System.” https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/planned-government-spending/expenditure-management-system.html.

- 1 Examples of organizational spending evaluations include: an evaluation of the Family Reunification Program by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; an evaluation of the Industrial and Technological Benefits Policy by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada; and an evaluation of the departmental Use of Selected Consulting Services by Public Services and Procurement Canada.

- 2 This provision gives substance to the requirement in the Financial Administration Act that grant and contribution programs be evaluated for relevance and effectiveness every five years.

- 3 See the 2024-25 Government Expenditure Plan and Main Estimates (Parts I and II). https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/planned-go…

- 4 Authority is granted under Standing Order 108(3)c(x).

- 5 House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates, Strengthening Parliamentary Scrutiny of Estimates and Supply (June 2012). https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/41-1/OGGO/report-7/

- 6 House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates Improving Transparency and Parliamentary Oversight of the Government’s Spending Plans. https://www.ourcommons.ca/documentviewer/en/42-1/OGGO/report-16/page-24

- 7 Parliament of Canada Act, paragraph 79.2. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/P-1/page-8.html#docCont.

- 8 Parliament of Canada Act, paragraph 79.01.

- 9 For a detailed discussion of how the measures presented in the federal tax expenditure report can be classified as substitutes for program spending and as measures intended to promote a fair and efficient tax system, see Lester (2012) and Robson and Laurin (2017).

- 10 Since 2020, Finance Canada has published outcome-based evaluations of two pandemic-related programs – the Temporary Wage Subsidy and the Canadian Emergency Wage Subsidy – and the tax-free rollover of investments in small businesses.

- 11 While there have been public reviews of some transfer programs, the Canada Child Benefit has not been publicly evaluated since it was implemented in 2016 as a replacement for the Canada Child Tax Benefit, the National Child Benefit Supplement, and the Universal Child Care Benefit. The Equalization program, which accounts for 5 percent of program spending, has been renewed every five years since 2014 without any public review of the program.

- 12 Some departments publish their evaluation plans.

- 13 Agriculture and Agrifood, Employment and Social Development, Environment and Climate Change, Heritage, Infrastructure, Innovation, Science and Economic Development, Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship, and Natural Resources.

- 14 Regulations must pass a benefit-cost test prior to implementation. See the Cabinet Directive on Regulation (section 5.2.1), which is available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/laws/developing-improving-fe…

- 15 This is a comparison of the forecasts for 2024/25 in the 2019 Economic and Fiscal Update (EFU) and the 2024 Budget for program spending excluding net actuarial losses on employee pension funds and the return of pollution pricing revenues. Projected adjusted program spending for 2024/25 was 13.8 percent of GDP in the 2019 EFU and 15.5 percent of GDP in the 2024 budget. The difference in levels is $83.7 billion.

- 16 The 12 countries are Austria, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Latvia, Netherlands, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

- 17 The Sustainable Fiscal Planning and Reporting Act constrains growth in operating expenses to the rate of population growth plus inflation.

- 18 Incremental costs arising from changes in program parameters would be included.

- 19 These include operating costs beyond employee compensation and consultants’ fees; provisions for legal claims, guarantees, and environmental liabilities recorded as expenses; and net actuarial losses on employee pensions.

- 20 Following this procedure will likely show spending declines over time because funding for voted programs is fixed in nominal terms over the life of the program, which is often shorter than the medium-term forecast. The decline could be offset by increases in the policy reserve, if that is deemed appropriate.