The Study in Brief

- Canadians have been debating whether Canada’s regulatory and permitting processes strike the right balance between attracting investments in major resource projects and mitigating potential harm from those investments.

- These regulatory processes typically apply to complex and expensive projects, such as mines, large hydrocarbon production projects (oil sands, liquefied natural gas [LNG], offshore oil), electricity generation (hydroelectric dams, nuclear), electricity transmission (wires), ports and oil or natural gas pipelines. These projects often involve multiple levels of jurisdiction and can prove particularly slow to gain government approval.

- Canada struggles to complete large infrastructure projects, let alone cheaply and quickly. We propose improving major project approval processes by: (a) ensuring that provincial and federal governments respect jurisdictional boundaries; (b) leaving the decision-making to the expert, politically independent tribunals that are best positioned to assess the overall public interest of an activity; (c) drafting legislation with precision that focuses review on matters that are relevant to the particular project being assessed; and (d) confirming the need to rely on the regulatory review process and the approvals granted for the construction and operation of the project.

The authors thank Jeremy Kronick, Benjamin Dachis, Monica Gattinger, Jim Fox, Glen Hodgson, Greig Sproule and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier draft. The authors retain responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

Introduction

This Commentary addresses investment-chilling perceptions that Canada’s regulatory regimes to assess and approve large infrastructure projects are slower and less certain than they ought to be. Largely focusing on complex projects involving the federal government, we examine the economic case for reliable and timely approvals, then examine Canada’s current practices, analyze their impacts and make recommendations for improvement. We focus on major projects that are regulated because they may involve potential harm, often environmental, rather than those regulated for monopoly concerns.

Complex physical projects often involve several levels of government: federal, provincial, territorial, Indigenous and municipal. In the interest of space and expertise, we mostly limit our analysis to federal and provincial relationships, though the principles we develop may apply to others. This is not to ignore the importance of other communities, particularly Indigenous ones, which are often affected by large projects. To the contrary, we take as a given the necessity of fully and appropriately including relevant Indigenous communities in developing all projects.

Consistent and respectful policies and procedures for consultation with Indigenous groups that reflect and are consistent with decades of case law are fundamental to the success of any major infrastructure project.1 The trend to increased equity participation by Indigenous groups in major projects is surely a significant step in the right direction.2

We find that uncertainty about project approval decreases investment at the margin, amid a trend of falling current and planned resource investment, which can foreshadow weaker economic growth and productivity. We find that processes could be improved by greater federal and provincial cooperation, relying on politically independent tribunals, avoiding jurisdictional overreach, through a sharp focus on ensuring steps are only as complex as needed and no more, and fostering an overarching ethos that fosters private investment in major projects.

Permitting: A Critical Piece of the Puzzle

Many factors go into investors’ decisions as to where to spend their money. To name a few: expected future product pricing, actions of competitors, the amount and quality of available labour, costs of inputs like power and equipment, and taxation on their profits.

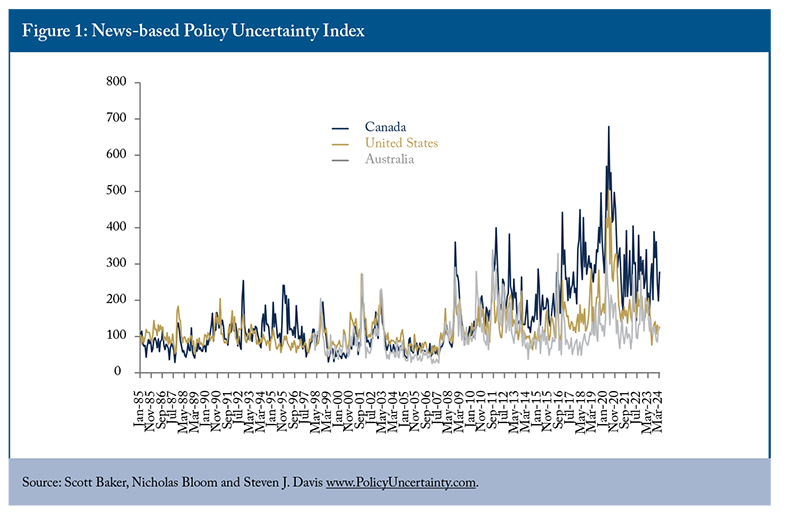

Assessing a potential project’s benefits and risks, and their probabilities, is daunting. Doing so in a jurisdiction where rules could change is even harder. Assessing that likelihood is difficult, but some researchers have tried. Using a survey of news sources, a trio of academics developed an index of uncertainty based on the frequency of certain terms (Baker, Bloom, and Davis 2016). They have developed an index for several countries, including Canada.

Using this index, Figure 1 compares Canada with the US, arguably Canada’s main competitor for overall investment. Australia is also included as a competitor for natural resource investment. The chart shows a relatively higher level of Canadian economic policy uncertainty in recent years, which conceivably indicates a less attractive investment environment.

Regulatory Assessment Costs

More narrowly, and to this Commentary’s point, investors must consider the underlying regulatory environment. Project proponents assessing a potential investment undertake it only if the net present value (NPV) of the benefits exceeds the costs, a calculation that includes the cost of the capital needed to complete the project, a factor that includes different regulatory costs. It is, therefore, important to get regulation of major projects right. So, while well-designed regulatory assessment should address negative externalities, it should do so in such a way as to otherwise maximize investment.

Regulatory assessment costs can take several forms: direct costs, costs of uncertain approvals, time costs of long processes and contingency costs.

To begin, there are the out-of-pocket costs needed to complete approval applications, undertake required business and environmental reviews (either in-house or by consultants), legal costs and other administrative support costs. These can reach the hundreds of millions of dollars for complex major projects.

Perhaps less obvious are costs driven by time or uncertainty. The longer the approval process takes, the higher the profitability bar must be raised to offset the costs incurred by paying staff prior to receiving revenue and forgoing investments should funds be needed to be kept liquid. Further, if a proponent considering an investment is unsure whether a project will receive approval at all, it is less likely to even start the approval process.

Scanning news sources, one may get the impression that large projects approved routinely face rejection later. In fact, projects are rarely denied approval outright. Importantly, though, even one denial may send the message that it could happen to any prospective project. That kind of risk perception may loom much larger in the minds of proponents than indicated by simple statistical probabilities. Even so, perception and signals matter to investors. The federal government’s 2016 cancellation of the Northern Gateway pipeline project is emblematic of this risk.

Contingent spending arising from the approval itself also typically increases costs. For example, Canada’s federal government approved the Bay du Nord Newfoundland and Labrador offshore oil project in April 2022 but attached 137 conditions.3 While conditions are an expected part of project approval, proponents typically incur additional costs that accompany those conditions.

While multiple global studies have shown that large construction projects of several types commonly cost more than initially estimated, for several reasons (Siemiatycki 2015), it ought to be the case that we minimize uncertainty where we can, and permitting is an example of low hanging fruit.

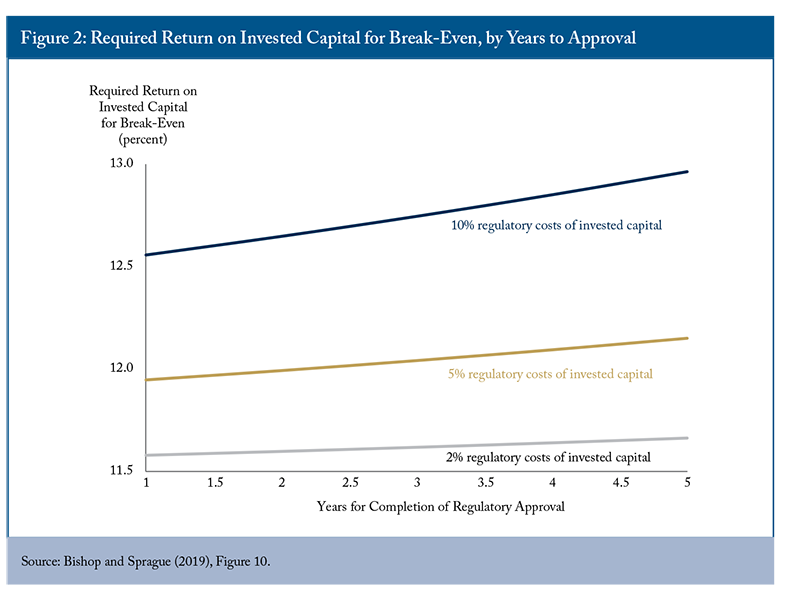

Regulatory Risk Impact

The figures below draw on previous C.D. Howe Institute work to show how greater regulatory costs and length of the regulatory process increase the required rates of return. At the margin, this makes investment less likely (Bishop and Sprague 2019).

Investors in potentially contentious projects require a greater expected return based on the greater the risk of rejection and the longer expected approval time. These expectations rise with the amount of capital it takes to make an application. Reducing application costs, speeding up time to approval and reducing the rejection risk all work to reduce required breakeven costs, raising the chance of investment.

How is Canadian Resource Development Doing?

As Robson and Bafale succinctly put it, “High or low levels of capital and productivity tend to go together (2023, 2).” Unfortunately, things have been trending the wrong way. New investment per worker in Canada was only 57 cents per US worker in 2022. Though direct comparison is challenging, it also appears lower than OECD counterparts (Robson and Bafale 2023).

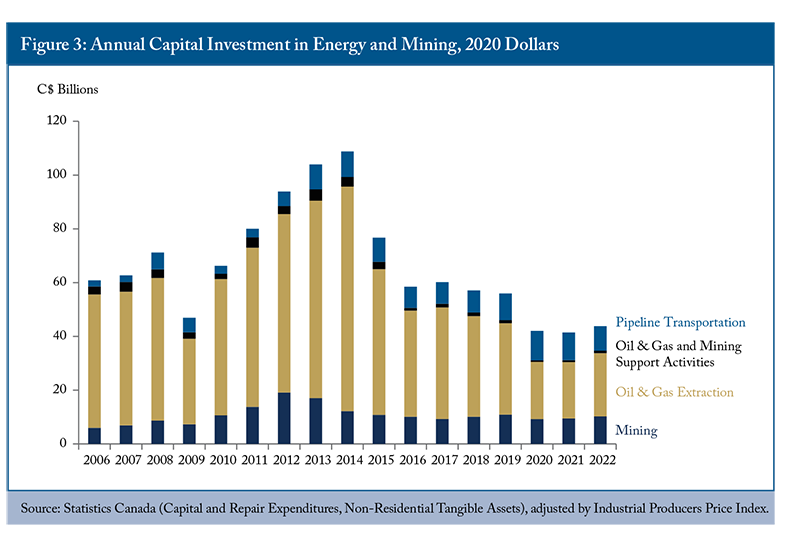

As it happens, the sectors that have driven Canadian business investment in the past, but are now trending downwards, are precisely the ones affected by complex regulatory procedures. Indeed, electric power generation, transmission and distribution; oil and natural gas extraction (normally leading all sectors); and mining combine for billions of annual investment.4

Furthermore, Canada’s natural resources sectors (mining and oil and gas extraction) have historically been among the most highly productive sectors per unit of labour, although by some measures this has fallen in recent years.5 In the past, they have supported strong investment throughout the supply chain, high workers’ incomes, and high levels of government royalties and taxes. These sectors are, therefore, highly valuable parts of Canada’s economy, while at the same time their inherent characteristics mean they, and their supporting infrastructure like pipelines, are among the most likely to require regulatory assessment.

Investment in resource extraction has been positively correlated with commodity prices. This occurred in the oil price drop in 2015, when the average West Texas price per barrel dropped almost in half, from US$93.17 in 2014 to US$48.66 in 2015.6 Despite a rebound to higher prices, investment, especially in oil and gas, has been weak for several years (Figure 3). Adjusted for inflation, capital investment in mining and oil and gas extraction in 2022 represented about 42 percent of the high point in 2014. The years prior to 2015 might be somewhat overstated: it is conceivable that the global oil boom pushed up material and labour costs to a point where investment overstates activity. Even so, 2022 investment was only about 69 percent of that in 2019.

Inventory Outlook and International Comparisons

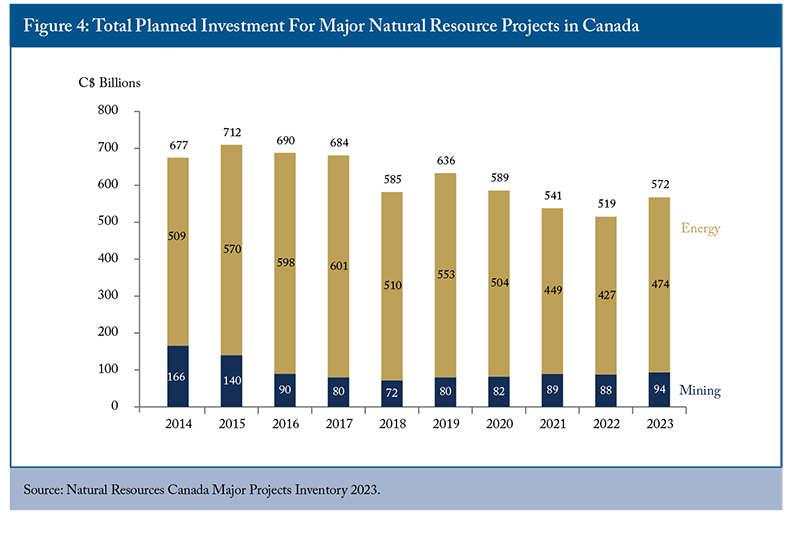

Natural Resources Canada’s Major Projects Inventory tracks major projects currently under construction or planned within the next 10 years, a measure that can indicate future investment. While the inventory has rebounded somewhat from post-pandemic lows, adjusted for inflation, energy and mining project spending remains far below its 2015 peak (Figure 4).

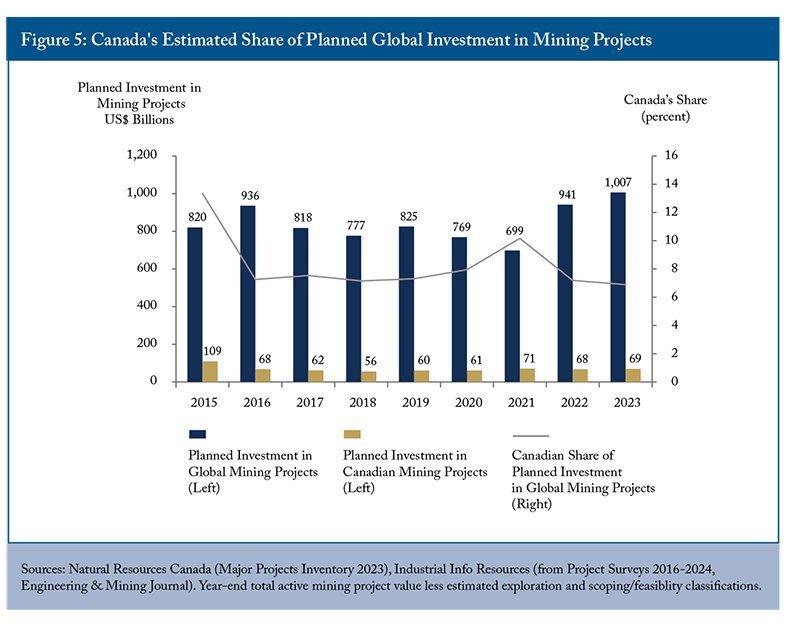

Many observers foresee the need for greater amounts of mined metals and minerals.7 How is Canada and the world responding to this mining challenge? Figure 5 shows Canadian planned mining investment compared with overall global estimates. After a pandemic-induced decline in 2020 and 2021, global mining investment plans have increased substantially in the past two years. While Canadian mining investment has remained relatively steady since 2016, its relative share has dropped more recently.

Acknowledging that capital declines can have many causes apart from permitting concerns (input cost pressures, uncertain future demand, future revenue prices, capital availability concerns, to name a few), the overall decline is worrisome. The decline in natural resource extraction investment, normally the largest component of capital investment and one of the most productive, has not been replaced by much else.

What are the Opportunities?

If Canada is to capture a greater share of rising global mining investment, it needs to do more. Given Canada’s generous natural endowment, skilled workforce and other attributes, doing so seems eminently possible. Indeed, there is reason to believe Canada faces strong long-term demand for its resources.

Oil and gas investment will remain a backbone of Canadian capital investment in coming years. For example, Canadian oil sands companies are globally competitive on cost and should continue to weather short-term price dips (Fellows 2022). LNG Canada, a liquefied natural gas terminal being built in BC, is the largest single private-sector investment ($40 billion) in Canada’s history and should be completed by 2025. In addition, Cedar LNG has been approved under the federal Impact Assessment Act (via a substitution agreement with BC) and other projects like Woodfibre LNG and Tilbury LNG are also under development.

Looking further ahead, lower-GHG-emitting electricity production and electric vehicles require critical minerals such as copper, lithium, cobalt, nickel and rare earth elements. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global demand for these elements to grow, and Canada’s rich endowment of resources could play a critical role.8 IEA head Fatih Birol has said he prefers that countries like Canada take the lead and the sooner the better.9

As Canada and the world continue to demand all kinds of manufactured goods, including those designed to reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, mining will be needed to produce the necessary metals and minerals. Manufacturers of electric vehicles, wind and solar generation, electricity transmission, battery storage and others will all demand them. While analysts expect recycling to form a growing part of supply, mines are still needed. Indeed, the federal government’s Critical Minerals Strategy,10 favours a plan to “…increase the supply of responsibly sourced critical minerals and support the development of domestic and global value chains for the green and digital economy.”

What Are We Doing About It?

Canada’s federal government acknowledges there’s a problem. Over a year ago, Budget 2023 promised to outline a concrete plan to further improve the efficiency of the permitting and impact assessment processes for major projects. More recently, the federal government’s 2023 Fall Economic Statement stated:

For Canada to build a thriving economy, investments in clean projects – from critical minerals to clean electricity, to clean energy and beyond – must be able to move forward quickly and effectively. Canada is a world leader in getting these projects done right – with strong environmental protections, robust labour standards, and engagements with Indigenous partners. However, more needs to be done to ensure major projects get built in a timely manner. (Fall Economic Statement 2023.)11

Furthermore, the government has formed the Ministerial Working Group on Regulatory Efficiency for Clean Growth Projects, a cross-ministry body formed to take “…action to improve federal regulatory and permitting processes to make them more efficient, transparent and predictable.”12 Most recently, Budget 2024 announced further measures intended to reduce timelines: funding to the Privy Council Office’s Clean Growth Office to implement Working Group recommendations; creating a new Federal Permitting Coordinator; establishing time targets of five years for federally designated projects and two years if not; driving culture change to do things faster; building a Federal Permitting Dashboard; and streamlining nuclear projects with the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission.13

The 2024 Budget also announced welcome efforts to improve Indigenous investment, including but wisely not limited to, natural resources projects through a Loan Guarantee Program and to improve federal consultation.

Time to Rethink “Clean” Labels

More does need to be done, yet the continued focus on so-called “clean” projects, while seemingly reasonable as an outcome, is troubling. First, the term is meaningless without an established definition of “clean.” Second, by establishing whether something is clean before it can be assessed, the terminology implies a two-tier assessment framework.

Each project ought to be assessed on its merits within a consistent framework. Applying prejudicial labels ex ante without a clear rationale serves no positive purpose. Such labelling confuses investors and casts doubt about whether an investment is welcome at all. Any projects gaining approval ought to be considered “clean.”

Considering that the Bank of Canada recently warned that Canada faces a serious “productivity problem,”14 all sorts of capital and technological investment are needed. Within a system in which each project undergoes fair and equal assessment, policymakers ought to seek out and celebrate investments of all kinds.15

In improving and streamlining Canada’s regulatory system, policymakers face many complex decisions. With each choice, we strongly suggest they keep in mind some simple yet powerful overarching principles: 1) there is no “good” or “bad” investment category and 2) more investment is good for Canada.

With this in mind, and to contribute constructive suggestions, the following sections describe the current set of regulatory processes major projects must undergo, identify potential chokepoints that inhibit efficiency or increase uncertainty and suggest potential improvements to permitting processes.

Improving Regulatory Efficiency

What are the primary issues that need to be addressed in order to create more competitive regulatory review processes in Canada? Many of the issues are the same ones that practitioners have raised for decades and still remain unresolved. This is key for legislators to understand. While the problems with our regulatory processes are not new, we now have an opportunity to learn from past mistakes and to make the necessary improvements.

In Budget 2024, released on April 16, 2024, the federal government promised to reform certain regulatory processes under the heading “Getting Major Projects Done.”16 Specific major project types mentioned were clean electricity, critical minerals and nuclear energy, which seem to be the focus of the federal government’s clean-growth or net-zero agenda. Other promises included providing certainty for businesses and investors, avoiding duplication with assessment processes undertaken by the provinces and “targeted” timelines to get federally designated projects through the approval process within five years and non-designated projects within two years.

To achieve these objectives, it will be imperative, at a minimum, that the following be considered as legislation is reviewed, amended and developed: (a) recent judicial decisions that provide guidance on the divisions of powers between Ottawa and the provinces concerning the regulation of environmental and regulatory matters; (b) leaving public interest determinations to the level of government that regulates the life cycle of the activity; (c) drafting legislation with more precision to increase certainty and reduce litigation risks; and (d) ensuring that the administration of approvals post-decision is consistent with the initial approval decision. Each of these issues is discussed further below.

As noted earlier, while this Commentary does not focus on specific recommendations and policies for involvement by, and consultation with, Indigenous groups, doing so is needed for success.

We also acknowledge that this Commentary covers only some of the issues that require addressing to achieve more efficient processes and, while it primarily discusses concerns at the federal level for illustrative purposes, ultimately both Ottawa and the provinces need to work together to achieve efficient and competitive regulatory processes.

Path Forward – A Starting Principle of Cooperation

The Supreme Court of Canada’s (SCC) recent opinion concerning the constitutionality of the Impact Assessment Act(IAA) and the Physical Activities Regulations (Regulation) provides the necessary launching pad to address these issues, once and for all.17 In a five-to-two opinion, the SCC held that virtually all sections of the IAA and the Regulations were unconstitutional (the IAA Reference Case). The result is that amendments to the IAA are required to address the Court’s concerns. In terms of the path forward, Chief Justice Wagner in the IAA Reference Case provided legislative guidance:

As I stated at the outset, there is no doubt that Parliament can enact impact assessment legislation to minimize the risks that some major projects pose to the environment. This scheme plainly overstepped the mark. But it remains open to Parliament to design environmental legislation, so long as it respects the division of powers. Moreover, it is open to Parliament and the provincial legislatures to exercise their respective powers over the environment harmoniously, in the spirit of cooperative federalism. While it is not for this Court to direct Parliament as to the way forward, I note “the growing practice of resolving the complex governance problems that arise in federations . . . by seeking cooperative solutions that meet the needs of the country as a whole as well as its constituent parts” (Reference re Securities Act, at para. 132). Through respect for the division of powers in Canada’s constitutional structure, both levels of government can exercise leadership in environmental protection and ensure the continued health of our shared environment (Hydro-Québec, at para. 154).” [emphasis added.]18

As emphasized, in the Court’s view it is incumbent on both levels of government to work together in a manner that respects the division of powers under the Constitution Act and that strives to reflect both the more local objectives of the provinces as well as national objectives.

The federal government released proposed amendments to the IAA on April 30, 2024.19 However, as we discuss further below, much more is needed to achieve the regulatory efficiency and clarity necessary to promote investment in major projects. Indeed, whether the proposed amendments are sufficient to support the constitutional validity of the IAA remains very much an open question. At the very least, a constitutional question mark will continue to hang over the IAA creating uncertainty for investors at the outset. This is unfortunate and unnecessary as there are thirty years of case law concerning the various versions of federal assessment legislation providing the necessary guidance to support a constitutionally valid statute.

The Jurisdictional Divide

The IAA Reference Case provided an opportunity to address some problematic regulatory issues, starting with amendments to the federal review process designed to ensure that it focuses on matters that are truly areas of federal jurisdiction. The SCC held that the constitutional deficiencies within the IAA were largely associated with an overly broad definition of “effects within federal jurisdiction.”20 The defined term neither aligned with federal heads of power under the Constitution Act nor did it drive the decision-making processes under the IAA. Broad references to any effect, positive or negative, on fish and fish habitat, migratory birds and Indigenous groups, for example, were not sufficiently precise to be supported by the various powers granted to Parliament under the Constitution Act. Incorporating references to climate change and sustainability in the decision-making process were also constitutionally problematic as these are not “federal effects.”

The Court’s views on “effects within federal jurisdiction,” as defined within the IAA, were as follows:

Due to the overbreadth of this definition, the scheme permits the Minister to designate a project based on effects that cannot be regulated from a federal perspective, to impose conditions in relation to these effects, or to declare these effects not to be in the public interest and put a permanent halt to the project as planned.21

Ultimately the Court found that the legislation was so broad that it would be “difficult to envision a proposed major project in Canada that would not result in any activities that ‘may’ cause at least one of the enumerated effects.”22 The result was that if the proposed activity was listed as a “designated project” in the Regulations, it was virtually impossible, except in the most obvious of cases, to then determine the basis upon which the federal government might assert jurisdiction, given the breadth of “effects within federal jurisdiction.” Given that the IAA makes it an offence to proceed without the project having been screened out of the impact assessment process because it was not determined to have effects within federal jurisdiction or having completed an environmental assessment, a project proponent would essentially have no choice but to freeze the project without specifically knowing what areas of federal jurisdiction were at issue, or risk prosecution.

Overreach to this extent inevitably means that the basis upon which the Act is engaged (i.e., “triggered”) is unclear, and that the federal government would be reviewing and making decisions on matters that are under provincial, not federal jurisdiction. The Court stated that the IAA permitted “… the decision maker to blend their assessment of adverse federal effects with other adverse effects that are not federal, such as the project’s anticipated greenhouse gas emissions…”.23

Not only does overreach by the federal government create regulatory and litigation risks, it also seems self-evident that federal decision-making based on non-federal effects (such as greenhouse gas emissions from a project, as noted by the SCC in the reference provided immediately above) inevitably leads to overlap and duplication with provincial review processes.24

The proposed IAA amendments do not adequately address this concern. While the changes provide some modest constraints, the constitutional basis upon which the IAA is engaged or triggered remains unclear. Instead of being based on any “effect within federal jurisdiction,” the proposed amendments modify the wording to “adverse effects within federal jurisdiction” that result in “non-negligible” changes to matters over which the federal government purports to have jurisdiction. These proposed amendments do little to provide certainty to project proponents concerning when the legislation would apply. What is and what is not a “non-negligible” change to an area of federal jurisdiction is essentially left to the imagination of the reviewing agency or minister.

The IAA Reference Case provided an important reset to the jurisdictional dividing line between levels of government in regulating natural resources and other major projects. Simply stated, the SCC reinforced that the level of government that regulates the “activity” has broad scope to regulate environmental issues, but that such scope is much narrower for the jurisdiction that merely regulates a “resource” or “effect.” For example, in the case of a mining project on provincial lands, the province will broadly regulate the mining activity. Indeed, provincial legislation will typically regulate all primary aspects of the mining activity from initial authorization through to decommissioning and reclamation.

Parliament may also have a role, typically much narrower, if the mining activity has the potential to negatively impact a matter that falls squarely within federal jurisdiction, such as harmful impacts to fish habitat requiring an authorization under the Fisheries Act. In these circumstances, the federal oversight should not extend to the mining activity as a whole, but instead to those aspects that are truly federal – in this example to fish and fish habitat.25 To achieve efficiency and to reduce overlap and duplication, federal involvement in assessing the activity must be limited to federal aspects.

Conversely, where the federal level of government regulates the life cycle of the activity, for example in the case of interprovincial and international works and undertakings, then it can regulate broadly, including making a determination as to whether the activity is in the overall public interest. This is generally how it works today. The courts have rejected attempts by provincial legislatures to impose targeted legislation purporting to regulate inter-provincial (i.e., federal) works and undertakings such as inter-provincial pipelines.26

The same principle should apply to similar attempts by Parliament to regulate in areas that are under provincial jurisdiction. Simply put, the provinces are best positioned to regulate local works and undertakings, whereas the federal level of government is best positioned to regulate federal works and undertakings.

What is required in an amended IAA is clarity as to when it applies and much more focus on tying the legislation to actual federal jurisdiction. Significant regulatory efficiency and certainty would be achieved by ensuring that federal environmental assessment legislation is engaged only in circumstances where constitutionally valid federal decisions are required and only for major projects likely to have significant federal environment effects. The IAA as currently drafted or with the proposed amendments does not necessarily tie the impact assessment to federal decisions required for a particular project. In fact, in some cases, no federal approvals or decisions are required but for the IAA itself. Limiting federal environmental assessment to clear federal decision-making (such as the issuance of a federal permit for a project) will ensure that the federal government targets matters within its jurisdiction and expertise. The result would be less overlap with provincial jurisdiction leading to a more predictable and efficient review process.

Public Interest Determinations

For major energy and natural resource projects, the appropriate decision-makers are expert administrative bodies that oversee the life-cycle regulation of such activities. We have many such regulators in Canada, both provincially and federally, some of which are recognized internationally as leading authorities.27 Such bodies have the requisite expertise in relation to matters that comprise the “public interest,” including environmental, safety, economic and social issues that arise in respect of the specific activities they regulate.28 Such authorities have oversight of all aspects of the activity from initial approval or authorization through to decommissioning and reclamation. As such, they are best positioned to make decisions in respect of the public interest.

Many provincial statutes regulating major projects include public interest decision-making structures. The IAA also links decision-making to a public interest test. Therefore, where the IAA overlaps with provincial regulatory statutes, two public interest decisions may need to be made in respect of the same activity. As found by the Court in the IAA Reference Case, the final IAA decision-making process was problematic when applied to projects regulated primarily by the provinces because it included a broad “public interest” test that was not truly focused on federal effects. Instead, the test included non-federal effects such as climate change and sustainability. The Court recognized that a negative public interest determination under the IAA prohibited the entire project indefinitely. This would be true even in cases where a province disagrees, deciding that an activity that it primarily regulates is nevertheless in the public interest.

Having two public interest decisions over the same project clearly adds an additional layer of uncertainty. If one level of government decides that a project is in the public interest while another disagrees, which decision prevails? The “public interest” determination should be reserved for the jurisdiction that regulates the life cycle of an activity and with the expertise to consider a broad range of public interest factors such as the environment, economy, safety, social issues and local context.

To address these concerns, broad public interest determinations affecting the activity as a whole should be made at the federal level only in circumstances where it has jurisdiction over the activity (for example, an interprovincial work or undertaking). In those cases, the public interest should be determined by the federal regulatory authority that regulates the activity. In cases where the province regulates the activity (for example, mining and power plants), the provincial regulatory authority that regulates the activity should determine whether it is in the public interest.

In cases where the federal government does not regulate the activity, but instead regulates an aspect of an otherwise provincially regulated activity, then the federal public interest test, at most, should be limited to only those matters that are federal (e.g., fish habitat) and not to the project as a whole. However, even this could be problematic if the result is that a broad public interest test leads to a decision that goes beyond the boundaries of the particular federal jurisdiction being exercised. For example, decisions in respect of fish habitat must be in relation to the “protection and preservation of fisheries as a public resource”29 and not matters such as greenhouse gas emissions.

Again, the proposed amendments to the IAA fail to adequately address the uncertainty of having the potential for differing broad public interest determinations in respect of the same activity from two levels of government. As noted, the SCC found the current public interest test under the IAA unconstitutional because it did not focus on areas of federal jurisdiction. Yet, under the proposed amendments, the decisions under the IAA would continue to be made on the basis of a broad public interest test.

Under the proposed amendments, it must first be determined whether “adverse effects within federal jurisdiction” are “likely to be, to some extent, significant and, if so, the extent to which those effects are significant.” If the effects are determined to be “significant,” the decision-maker must then determine if they are “justified in the public interest” based on a broad range of factors and remain largely unchanged by the amendments. The breadth of these provisions continues to create uncertainty in terms of how decisions will be made at the federal level and the extent to which such decisions will stray into areas of provincial jurisdiction.

Drafting Legislation and Procedural Directives to Minimize Uncertainty and Enhance Efficiency

Federal impact assessment legislation in its various forms has been the subject of extensive litigation and much more so than its provincial counterparts. Litigation adds to project uncertainty, creating delays and costs that can impact its overall viability. Careful drafting of legislation with clear and precise wording that respects the division of powers reduces the risk of litigation.

The constitutionality of the federal government’s early environmental assessment legislation, the Environmental Assessment Review Process Guideline Order (EARPGO), was litigated some 30 years ago. The SCC held that the EARPGO was constitutionally valid primarily because it was seen as merely procedural legislation designed to collect environmental information to inform federal decisions such as whether to issue an authorization under other valid federal legislation.30

The EARPGO was replaced by the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 1992 (CEAA 1992). The EARPGO and the CEAA 1992 were each structured to be engaged only when a valid federal decision in relation to an activity was needed, including decisions in relation to the following circumstances: (1) the federal government proposed the project; (2) the project occurred on federal lands; (3) the federal government might provide funding to the project; or (4) mostly commonly, when a specified federal authorization or permit was required for the project. Tying federal environmental assessment to federal decisions was not only constitutionally valid, it made it relatively straightforward to determine whether a particular project required federal assessment or not. These types of triggering provisions provided a level of certainty lacking in the IAA and ensured, at least at the outset, that the federal assessment legislation was engaged only when the federal government has some decision-making function in respect of an activity (also referred to as an “affirmative regulatory duty”).31

However, under the IAA, in either its current or proposed amended form, assessments are not tied specifically to valid federal decision-making such as the issuance of a federal permit for an activity. Instead, it is engaged in uncertain circumstances where there is the potential for “adverse effects within federal jurisdiction” that may cause “non-negligible” changes, and decisions are made based on the possibility of those effects being significant and if so whether they are justified based on federal priorities. In essence, the IAA becomes the decision-making legislation at the federal level for designated activities where the basis of the decision is unclear at least at the outset of the process. Moreover, the IAA would seem to allow decision-makers to regulate on the fly and impose conditions on or restrict activities on a case-by-case basis, including where federal authorizations or decisions would not otherwise be required.

For example, in a federal decision paper describing why certain activities were listed in the Regulations, Ottawa’s position seemed to be that it could regulate in cases where “projects that process or consume large quantities of oil and gas” may have “adverse effects to fish and fish habitat and migratory birds through land disturbance, air and water pollution and water usage, accidental spills, flaring, as well as through incidental activities that may be needed to transfer the oil and gas products to or from the facility or to provide power for the facility”(Canada 2019).32 Such an expansive interpretation of federal regulatory authority is constitutionally questionable and creates enormous uncertainty and risk for jurisdictional overreach.

While the CEAA 1992 was tied to federal decision-making, it nevertheless was the subject of significant litigation largely related to issues of statutory interpretation and the proper scope of federal assessment once the environmental review process was engaged. For example, if a bridge over fish-bearing waters (federal jurisdiction over fish habitat and navigable waters) was needed as part of a larger forestry activity (primarily a provincially regulated activity), the question was whether the federal environmental assessment should be limited to the bridge or whether it should cover the bridge and the forestry project. This question was never fully resolved by the courts prior to the CEAA 1992 being repealed. Arguably, however, the courts were leaning toward federal assessments being focused on federal aspects33 (i.e., in this example, the bridge and not the provincially regulated forestry activity). The associated uncertainty, delays and costs incentivized designing projects in a manner to avoid federal impact assessment (which could be suboptimal) or to forgo desirable projects altogether.

The CEAA 1992 was also problematic because it did not focus on major projects. The result was numerous lengthy environmental assessments for activities that largely did not warrant such an extensive review. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (CEAA 2012) replaced the CEAA 1992 and, in doing so, appropriately focused on major projects (seemingly resolving one of the primary concerns associated with the CEAA 1992). But it created a new problem by starting a transition from tying assessments to federal decision-making by introducing the concept of “effects within federal jurisdiction.” It is unclear why the drafters of the CEAA 2012 removed the triggering section found in the CEAA 1992 that limited environmental assessments to circumstances where federal decisions in respect of an activity were required. Unfortunately, the change created uncertainty as to when the CEAA 2012 applied. This fundamental change from CEAA 1992 was carried from the CEAA 2012 through to the IAA, ultimately leading to the IAA Reference Case and, as noted above, is not rectified by the proposed IAA amendments.

As discussed, the primary problem with the IAA was that it was not tied to valid areas of federal jurisdiction. Instead of being designed to merely inform federal decision-making, the IAA itself became the primary decision-making process where the criteria upon which decisions would be made were not federal. The result was significant uncertainty concerning the basis upon which federal jurisdiction was being asserted over an activity and, ultimately, what criteria would inform a federal public interest determination. As recognized in the IAA Reference Case, the IAA was so broad that it could capture virtually any activity.

To bring reasonable certainty going forward, an amended IAA or future form of federal assessment should be tied to valid federal decision-making similar to the EARPGO and the CEAA 1992. To ensure that federal environmental assessments are engaged only for activities that are likely to have significant environmental effects, a major projects list regulation should be maintained with a focus on major projects that are likely to involve a federal decision.

Federal environmental assessment legislation has also been extensively litigated over statutory interpretation that could be resolved with greater drafting precision. For example, as noted above, concepts such as the “scope of the project” to be assessed and the “scope of the assessment” to be conducted under the CEAA 1992 were repeatedly before the courts. Overly broad drafting of the definition of “designated project” under the CEAA 2012 also led to avoidable legal challenges.34

As discussed above, the IAA, including with its proposed amendments, continues to invite litigation based on ambiguous wording such as “non-negligible” changes to matters within federal jurisdiction and what effects are “likely to be, to some extent, significant and, if so, the extent to which those effects are significant.”

Other problems arise when requirements are mandatory with insufficient discretion granted to the reviewing agency to decide what is relevant for assessment purposes. For example, under section 22 of the IAA, all of the listed factors mustbe considered during an assessment. No discretion is granted to the reviewing agency to limit assessment to only those factors that are relevant to the particular activity being assessed. Allowing greater discretion under constitutionally valid legislation would not only reduce unnecessary assessment of irrelevant or marginal factors but also limit the role of the courts in reviewing assessments on the basis that not all matters were considered.

Next, it seems that the primary objectives of a well-structured regulatory process should be to ensure that a proposed activity meets applicable technical requirements, that environmental impacts are being appropriately managed and that directly affected stakeholders have an opportunity to be heard. Proponents should reasonably expect that the information requirements necessary to support a complete application are well defined in directives and guideline documents issued by the regulatory authority. Once applications have been filed, the review process should be clear with reasonable timelines to complete the various review stages. If public hearings are set, issues should focus on the project being applied for, and stakeholder participation should be limited to those with legitimate interests at stake.

Hearing from those with legitimate interests is achieved by limiting participatory rights to those individuals or groups that are truly directly and adversely affected by the activity. This would include individuals who own or occupy lands near the proposed activity or otherwise have legal rights that may be affected by the activity (e.g., Indigenous groups). Having unlimited participatory rights invites objections that contribute little to the process, creates unnecessary delay and effectively dilutes attention away from the concerns of those who are truly affected. To address this issue, legislation should be drafted to place reasonable limits on who can participate in the regulatory review process.

Finally, the question should be asked whether the nature and extent of the regulatory process is appropriate or excessive. It is important to weigh the time and financial costs with the overall benefits of the review process. Here, focusing on what the review process was intended to achieve is key. For example, the SCC in the IAA Reference Case commented on the original purpose of environmental assessment at the federal level as set out in earlier versions of the legislation. The purpose, the Court found, was simply to collect information about the environment to inform a federal decision as one part of an overall decision-making process.

Furthermore, according to the Court, the IAA legislation was procedural in nature, not substantive. But it evolved into something much more than that, becoming both an information-gathering process and the primary decision-making process, invoking a broad public interest determination based on federal priorities such as climate change and sustainability. The Act required proponents to provide extensive information on matters that would seem to go well beyond collecting environmental information to assist in making informed federal decisions. It included timelines that were lengthy and disproportionate to the nature and scope of review necessary to assess federal impacts. Indeed, despite being in force since 2019, only one major project had successfully completed the IAA process at the time of writing.35

In summary, focusing carefully drafted regulatory legislation on material issues that respect jurisdictional boundaries, is specific to the project at hand, provides clear application content requirements and review timelines, limits participation to those that are truly affected, and maintains the information-gathering aspect of environmental assessment will assist in providing for more efficient, predictable and timely review of major projects.

Can Investors Rely on the Process?

Once approved, the project proponent must then construct and operate the project in accordance with the authorization’s terms and conditions. Often, projects are approved on the understanding that the activity will have various environmental effects, sometimes of a significant nature, but that those impacts are justified in the circumstances because, overall, the project is in the public interest. Indeed, the concept of whether a significant effect is “justified in the circumstances” is one of the proposed amendments to the IAA. Multiple conditions are often included within authorizations, some of which are designed to mitigate but not necessarily eliminate those effects. After issuing approvals after completing extensive multiyear reviews, it is imperative that reliance can be placed on the outcome.

Certainly, an approval of a major infrastructure project that may have significant adverse environmental effects does not mean there is no requirement to comply with other environmental laws. Typically, however, there is significant discretion in most of our environmental laws, and it is important for that discretion to be exercised in a manner that is consistent with public-interest decisions that recognize that significant effects are likely to occur.

For example, it may be that after significant review of a pipeline project, it is concluded that, even with the implementation of appropriate mitigation measures, the project is likely to have significant adverse effects on migratory birds, but that the majority of impacts will be satisfactorily addressed, including habitat loss and disturbance and destruction of migratory bird nests. On this basis, the project can be approved.

The question then becomes, are those anticipated negative effects to migratory birds also approved? The answer must certainly be yes in terms of the overall approval for the project. But what about under the Migratory Birds Convention Act where it is an offence to, among other things, “destroy, take or disturb an egg”? Given the breadth of this prohibition, many activities that are undertaken on a daily basis have the potential to, for example, “disturb” the egg of a migratory bird. This necessarily means that the regulatory authorities that enforce such provisions must have broad discretion to decide when and to what extent such provisions should be applied in any given circumstance. In other words, not every disturbance of an egg or technical breach of an environmental regulation must or should be enforced.

If there is a disconnect between legislation in terms of what was approved, this has the potential to cause significant uncertainty and added costs during construction.

To address issues such as these in the future, it is important for regulatory authorities that have jurisdiction over aspects of the project to be aware of and consider the basis upon which projects were approved, in some cases at the highest levels of government including the federal cabinet. With this awareness, regulators would be in a better position to exercise their discretion in a manner that is consistent with such authorizations. The result, again, is overall increased certainty and efficiency with respect to major project development.

Similarly, once a project has been reviewed and approved and, in many cases, succeeded in post- approval litigation, a subsequent political decision to deny the project introduces an unacceptable level of uncertainty and risk for project proponents. Proponents seeking authorizations follow the regulatory process in good faith. The financial and other costs of participating in such processes can be extraordinary. Proponents reasonably expect to rely on the regulatory processes that they are subject to. Reversals at the political level should rarely occur and perhaps only in cases where the project is denied at the administrative level but is nevertheless deemed to be in the public interest. If circumstances do arise where an approval is reversed, then at the very least, the costs of the proponent to participate in that process should be reimbursed by the government making such a decision.

Conclusion

Canadians need ongoing investment to maintain and boost their standards of living. However, for a number of years business investment has been weak and productivity growth has suffered.

Major physical investments like ports, airports, pipelines, roads, electricity transmission lines, natural resource developments and manufacturing projects are complex, requiring a regulatory process to mitigate potential negative harms, while ensuring they can be completed. Canada’s current regulatory permitting system is slow, subject to seemingly random process and policy changes and deters potential investors. In light of our investment and productivity numbers, this must be addressed.

We propose improving major project approval processes by (a) ensuring that provincial and federal governments respect jurisdictional boundaries; (b) leaving the decision-making to the expert tribunals that are best positioned to assess the overall public interest of an activity; (c) drafting legislation with precision that focuses review on matters relevant to the project being assessed; and (d) confirming the need to be able to rely fully on the regulatory review process and the approvals granted for the purposes of the construction and operation of the project.

- 1 The Business Council of Alberta paper Future Unbuilt addresses this issue in greater detail. It touches on the lack of federal department coordination in respect of Indigenous consultation and suggests a [federal] equivalent to the Alberta Aboriginal Consultation Office. This is a good recommendation. A Federal Indigenous Consultation Office that does all federal consultation could develop a set of policies and procedures that are consistent with the decades of case law on the issue and consistently apply them. Such an approach should reduce the risk of litigation on the basis of lack of consultation. Such policies and procedures should be developed in consultation with Indigenous groups and industry proponents.

- 2 For more on Indigenous partnerships, see Vivek Warrier, Luke Morrison, Ashley White and Stephen Buffalo (2021).

- 3 See https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/bay-du-nord-approv….

- 4 The electricity sector, while a crucial foundation of Canadian living standards, is not part of this Commentary’s focus. While Canada exports some power, power investments tend to be made by provincially regulated public sector entities to ensure domestic supplies of reliable and affordable electricity.

- 5 See https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610048001 and https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610020701&pickMe….

- 6 See https://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart.

- 7 See https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-ener….

- 8 See https://www.iea.org/topics/critical-minerals.

- 9 See https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-security-minerals-prod….

- 10 See https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/critical-minerals-in-canada/canadian-….

- 11 See https://www.budget.canada.ca/fes-eea/2023/report-rapport/chap3-en.html.

- 12 See https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/news/2024/02/chair-of-ministeria….

- 13 See https://budget.canada.ca/2024/report-rapport/chap4-en.html.

- 14 See https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2024/03/time-to-break-the-glass-fixing-cana….

- 15 This relates to social or political, not financial, desirability. Private investors and public entities make individual investment decisions.

- 16 See https://budget.canada.ca/2024/report-rapport/chap4-en.html.

- 17 Reference Re: Impact Assessment Act, 2023 SCC 23.

- 18 See IAA Reference Case at para. 216.

- 19 The proposed amendments were released as part of a Notice of Ways and Means Motion previewing implementation of the 2024 federal budget.

- 20 See IAA Reference Case, see for example para’s 6 and 190 to 203.

- 21 See IAA Reference Case at para. 182.

- 22 See IAA Reference Case at para. 95.

- 23 See IAA Reference Case at para. 169.

- 24 Chief Justice Wagner provided extensive commentary on why Parliament does not have broad jurisdiction to regulate greenhouse gases from projects that are primarily regulated by the provinces. For example, the Court emphasized that in the Reference re GGPPA, it upheld only a “narrow and specific regulatory mechanism” limited to carbon pricing of greenhouse gas emissions and cautioned that “[a]ny legislation that related to non-carbon pricing forms of [greenhouse gas] regulation – legislation with respect to roadways, building codes, public transit and home heating, for example – would not fall under the matter of national concern.” The Court went on to state: “If the matter of national concern recognized by this Court in the References re GGPPA does not extend to enabling the federal government to comprehensively regulate greenhouse gas emissions, then the inclusion of such sweeping regulatory powers in impact assessment legislation is likewise impermissible.”

- 25 The majority of the SCC in the Reference Case stated the following in this regard at paragraph 177: “Parliament can validly regulate only the impacts that fall within its jurisdiction or that arise from activities within its jurisdiction.”

- 26 See, for example, Reference re: Environmental Management Act (British Columbia) 2019 BCCA 181 (upheld unanimously by the Supreme Court of Canada.

- 27 Among those cited are the Alberta Energy Regulator, the Alberta Utilities Commission, the Canada Energy Regulator and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, just to name a few.

- 28 For example, as noted by the Federal Court of Appeal in respect of a National Energy Board decision under the CEAA, 1992: “No information about the probable future effects of a project can ever be complete or exclude all possible future outcomes. The appreciation of the adequacy of such evidence is a matter properly left to the judgment of the panel which may be expected to have, as this one in fact did, a high degree of expertise in environmental matters.” (Alberta Wilderness Assn. v Express Pipelines Ltd. 1996 CanLII 12470 (FCA) at para. 9.)

- 29 See R. v Fowler.

- 30 See Friends of the Oldman River Society v Canada (Minster of Transport) [1992] 1 SCR 3 (the “Oldman River”).

- 31 Ibid.

- 32 See Discussion Paper on Proposed Project List - Canada.ca.

- 33 See, for example: Friends of the West Country Assn v Canada (Minister of Fisheries and Oceans), 1999 CanLII 9379 (FCA), [2000] 2 FC 263.

- 34 See Tsleil-Waututh Nation v Canada (Attorney General), 2018 FCA 153; leave to appeal to the SCC denied in 2020. One of the issues in this case was whether project-related marine shipping ought to have been included as part of an assessment under CEAA, 2012 based on the definition of a “designated project” that included any “physical activity that is incidental” to the activity listed in the Regulations.

- 35 See https://cwf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/CWF-Federal-IAA-Under-Review-….