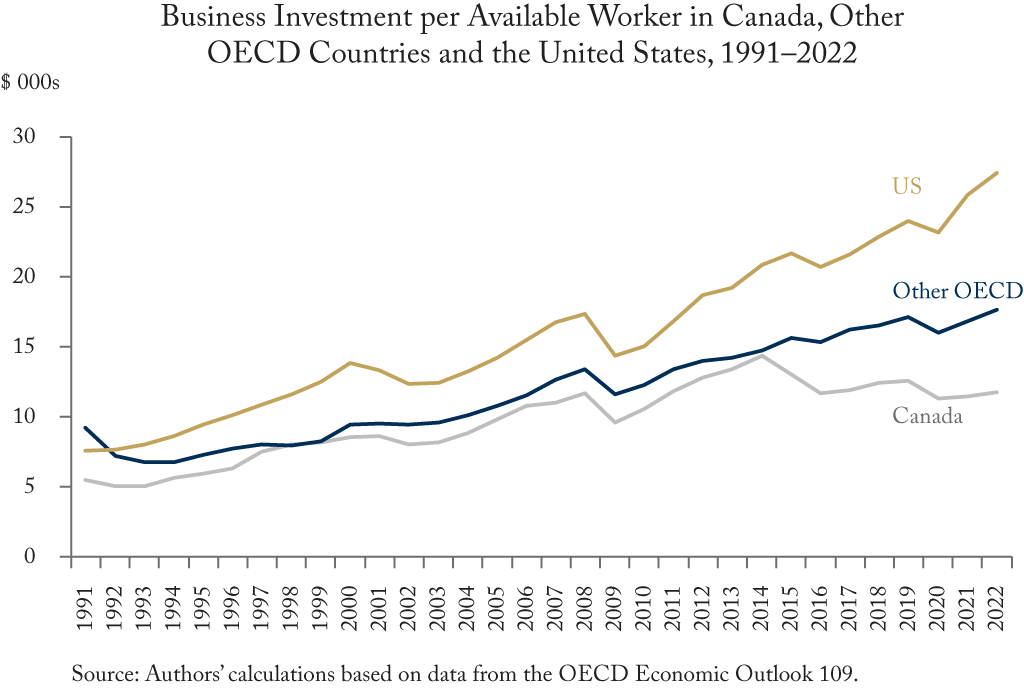

Canada’s stock of productive business capital is not keeping pace with its workforce. Since 2015, Canada’s stocks of capital per worker have been stagnant or declining and its rates of gross investment per worker have been weak. Moreover, business investment in Canada has been feeble compared to investment in the United States and other OECD countries, a contrast that appears to have worsened during COVID-19.

A long-standing gap between investment per member of the labour force in Canada and similar measures abroad narrowed between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s. For every dollar of investment per available worker in the OECD as a whole, their Canadian counterparts received about 75 cents in the early 2000s. By 2014, the Canadian figure reached 81 cents.

In 2021, however, Canadian workers will likely receive only about 58 cents of new capital for every dollar received by workers in the OECD as a whole, and the OECD’s projections yield the same 58-cent figure for 2022. Against the United States, the OECD’s projections for Canada yield figures of 48 cents for 2021 and 47 cents for 2022.

Higher investment rates are not a goal in their own right. Spurring investment in non-economic assets with subsidies or regulation could raise capital spending but lower productivity and future incomes.

These numbers are concerning because they suggest that Canadian businesses are not seeing opportunities and threats that would prompt them to undertake productivity-improving capital projects, or that they are seeing those opportunities and threats but are not responding to them.

Countries with higher capital intensity tend to have higher productivity and higher wages. Countries with lower capital intensity tend to have lower productivity and lower wages.

We want Canada to be in the first category, not the second.

To learn more about Canada’s looming investment crisis, please read “Declining Vital Signs: Canada’s Investment Crisis” by William B.P. Robson and Miles Wu.