The Study in Brief

-

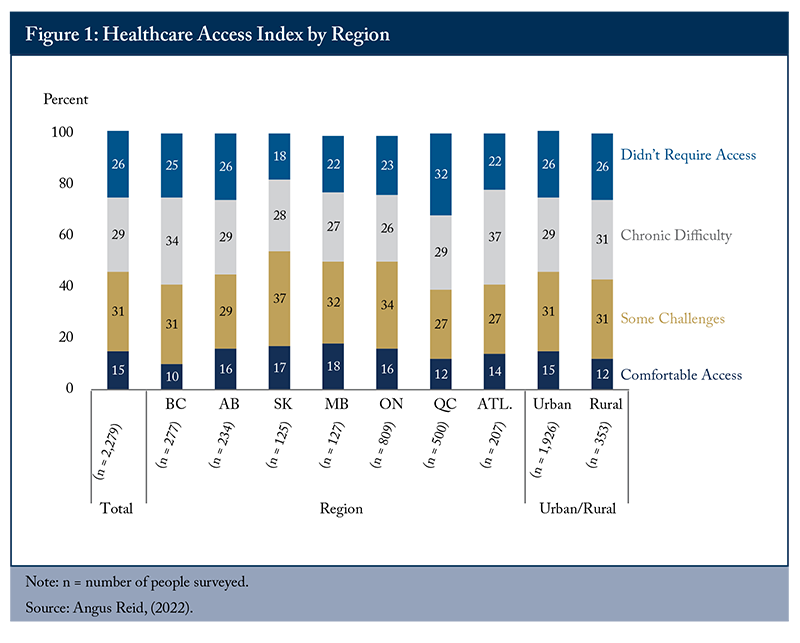

In the latest OECD national satisfaction survey on “availability of quality health care,” Canadians gave our healthcare system a mark well below the OECD average. In a large 2022 Angus Reid survey of access to health care, 60 percent responded that they face “chronic difficulty” or “some challenges.”

-

No single explanation of dysfunction – the COVID pandemic, aging of the population, inadequate public financing, or decline in physician hours – is satisfactory. Collectively, they are a partial explanation.

No single explanation of dysfunction – the COVID pandemic, aging of the population, inadequate public financing, or decline in physician hours – is satisfactory. Collectively, they are a partial explanation. -

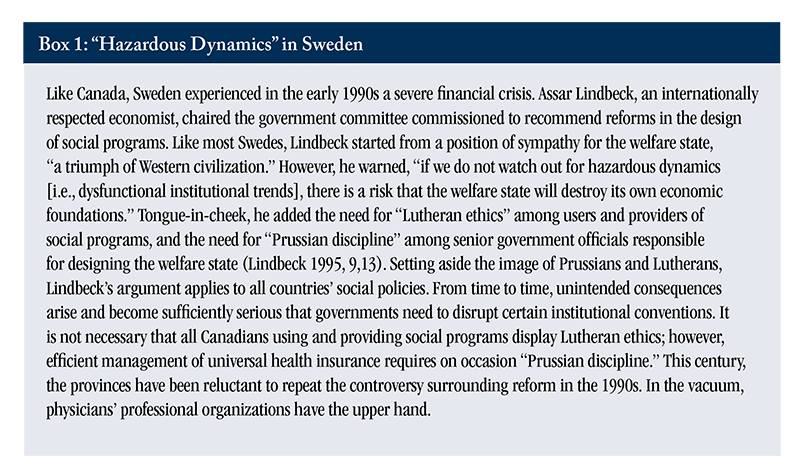

However, a major cause for the dysfunction is the reluctance of provincial governments to undertake institutional reforms, for fear of provoking interest groups – particularly physicians’ organizations. The provinces have not made major changes to their health delivery systems since forced to do so by the deficit crises of the 1990s.

However, a major cause for the dysfunction is the reluctance of provincial governments to undertake institutional reforms, for fear of provoking interest groups – particularly physicians’ organizations. The provinces have not made major changes to their health delivery systems since forced to do so by the deficit crises of the 1990s. -

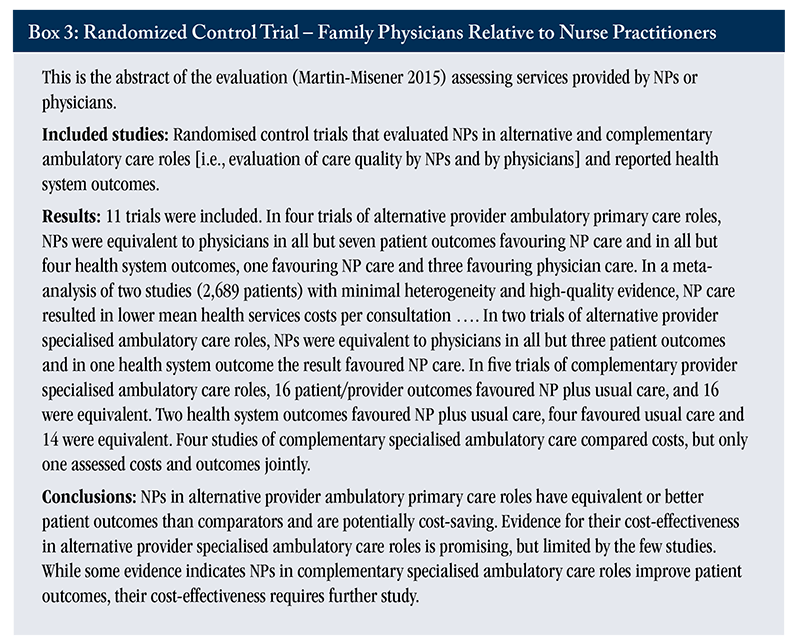

Studies have repeatedly shown that nurse practitioners can deliver equally good care as family physicians in most situations, while costing the healthcare system less. Capitation, where healthcare providers are paid based on how many patients they have on their roster, gives clinics the flexibility to adjust their services in response to patient needs, allowing better care at somewhat lower cost.

Studies have repeatedly shown that nurse practitioners can deliver equally good care as family physicians in most situations, while costing the healthcare system less. Capitation, where healthcare providers are paid based on how many patients they have on their roster, gives clinics the flexibility to adjust their services in response to patient needs, allowing better care at somewhat lower cost. -

The author recommends two targeted reforms:

The author recommends two targeted reforms:—an aggressive increase in the number of nurse practitioners working in community primary care, usually in multi-discipline clinics; and

—expansion, beyond Ontario, in rostering patients and expanding capitation in multi-discipline clinics.

For a modest monograph, I enjoyed exceptionally serious advice, criticism, and recommendations. I received advice from colleagues managing Mid-Main Community Health Centre, a multi-discipline clinic in East Vancouver. I received detailed comments throughout from Tingting Zhang, a C.D. Howe Institute analyst, Editor James Fleming, Rosalie Wyonch, Gherardo Gennaro Caracciolo, Don Drummond and several anonymous reviewers.

Introduction

Red queen to Alice: “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!” – Lewis Carroll

The provinces have been “running,” in terms of large annual health budget increases but, as the queen explained to Alice, they only enable us “to keep in the same place.” To get “somewhere else,” the provinces “must run at least twice as fast.” Annual budget increases are necessary but getting “somewhere else” requires controversial institutional change, particularly in primary care.

Every two years, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development publishes Health at a Glance (OECD 2021, 2023), a comprehensive source of comparative health statistics among member countries. A recurring item is a survey on access to quality healthcare. Results show a very large Canadian decline between 2019 and 2021. According to the 2019 OECD survey, 78 percent of Canadians responded that “they were satisfied with availability of quality health care.” This result was well above the 2019 OECD average (71 percent). In the 2021 survey, the Canadian score is 56 percent, a decline of 22 points. Admittedly, the latest survey took place during the COVID pandemic. However, all OECD countries experienced severe stress in provision of health services. What explains the Canadian decline, which is much larger than the four-point average decline (from 71 percent to 67 percent) among OECD member countries (OECD 2021, 2023)? As additional evidence on Canadians’ (dis)satisfaction, Figure 1 illustrates the results of a 2022 Angus Reid survey. Disaggregated by six provinces and the Atlantic region, the results are consistent with Canada’s latest OECD availability patient satisfaction score.

There are several plausible explanations for dissatisfaction, none of which are individually adequate. Collectively, however, they provide a reasonable explanation. Over the last two decades, physicians have reduced their hours worked per week. The trouble with this explanation is that “physician density” (physicians per 1,000 people) has increased, and the number of services per 1,000 people has been more-or-less stable. The pandemic led to exhaustion and stress among caregivers in the countries (including Canada) surveyed by the Commonwealth Fund (2022). However, Canadian COVID cases per million were well below the average among high-income countries.1 Independent of the pandemic, the aging of the Canadian population is increasing the per capita demand for health services, but it is not occurring at a faster pace than in other OECD countries. Nor is present Canadian spending likely to be the major factor. In terms of total (public plus private) health spending, Canada has been consistently above the OECD average in both percentage of GDP and expenditure per capita.2

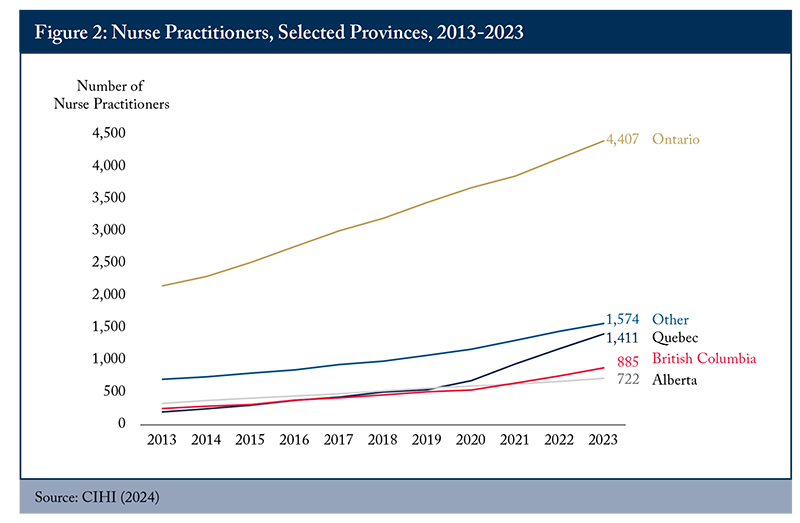

Underneath the collective impact of the above explanations is, I suggest, the general reluctance of provincial governments to reduce the influence of physicians’ associations in determining policy. Subject to some federal and judicial constraints, provincial governments have constitutional authority to design their health programs. Since the reforms of the 1990s, which were spurred by need to address fiscal deficits, most provinces have been reluctant to provoke opposition from powerful interest groups – in particular physicians’ organizations.3 Admittedly, over the last two decades Ontario has realized a significant increase in multi-discipline clinics, most of which have adopted a capitated remuneration formula (Blomqvist and Wyonch 2019). Also, relative to the nine other provinces, Ontario has made significant progress in employment of nurse practitioners (NPs) in community primary care (see Figure 2 below). Among many potential institutional reforms, this E-Brief emphasizes two:

—aggressive provincial strategies to increase the use of NPs working in community primary care, largely in multi-discipline clinics; and

—promotion of multi-discipline primary care clinics.

Relative to the mid-20th century, the expansion of social programs in the third quarter of the century required a far larger tax share of GDP and a much larger scope for government administration. By the 1990s, many high-income countries, including Canada, faced a serious fiscal deficit that could not be resolved without institutional reforms in health and other social programs. The case I know best is my home province, Saskatchewan. In 1991, it held the dubious rank as the province with the highest ratio of public debt to provincial GDP. Saskatchewan bonds were close to “junk” status. Despite extensive political opposition, the province substantially increased provincial tax rates and reduced public spending. By 1995, it realized a budget surplus. Among the major spending cuts was the closure of over 50 small hospitals, which had provided employment in small communities. For two decades, the provincial cabinet had known these small rural hospitals could not provide more than simple procedures, but had continued their operation nonetheless. Similar dynamics arose in the other provinces.

Influence of Physicians’ Associations

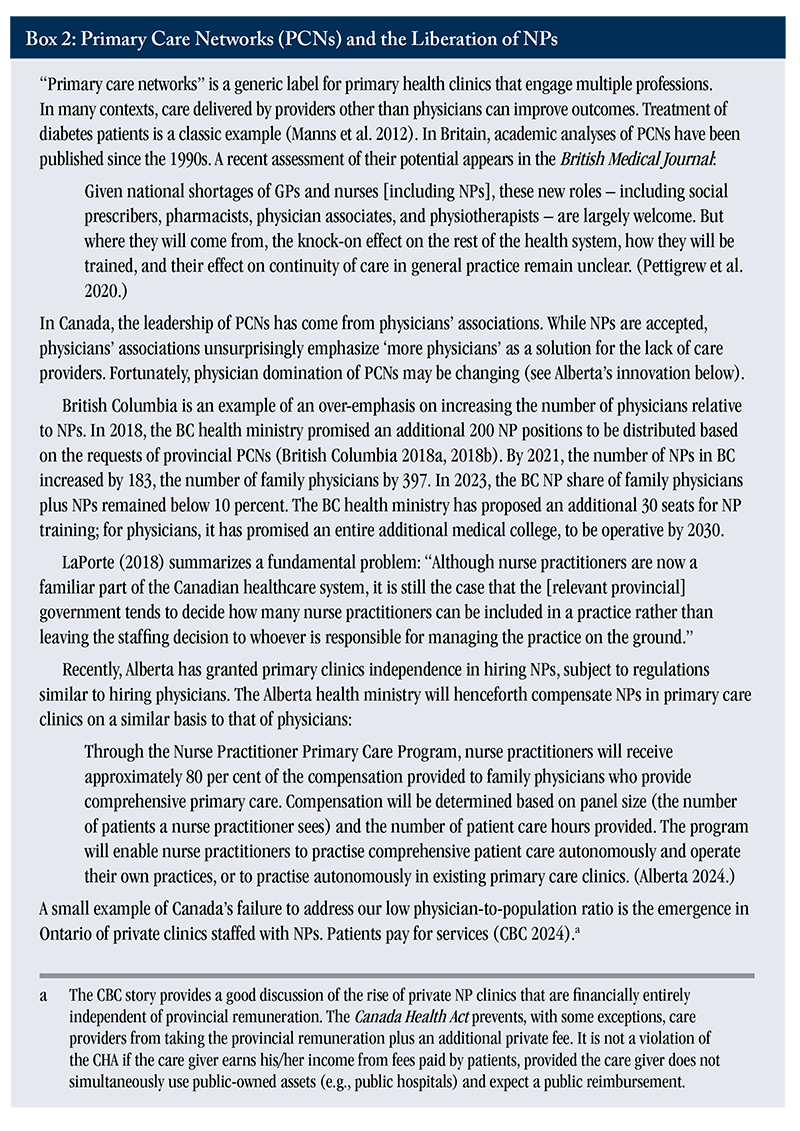

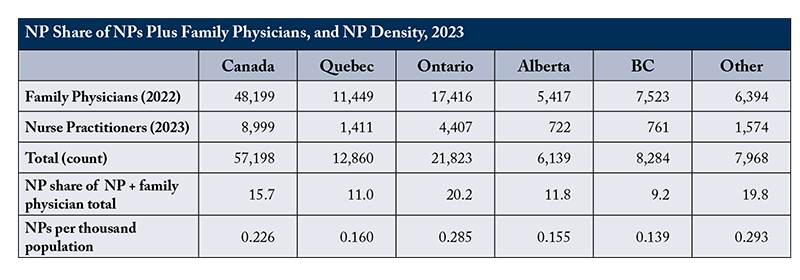

Based on their training, physicians are legitimately understood as the health sector’s “peak” profession, and their professional associations legitimately exercise considerable influence in shaping health policy. Provincial physicians’ associations can, for example, constrain competition arising from employment of nurse practitioners (NPs) in the provision of primary healthcare (see Box 2). All rigorous evaluations undertaken over the last quarter century have concluded that NPs deliver ambulatory primary care as well as family physicians do. At present, NPs comprise only 15 percent of the national NP + family physician total, and only a minority of NPs practice in the context of multi-discipline ambulatory health clinics. Admittedly, physicians’ associations have over time accepted an increasingly autonomous role for NPs. In most provinces there remain unnecessarily complex regulations negotiated by physicians’ associations and provincial governments.

The circumstantial evidence of excessive physician influence extends beyond the marginalized role of NPs. Canada has a high OECD ranking in normalized physician earnings, a low OECD ratio of physicians per 1,000 population, and a high OECD ratio of urban/rural distribution of physicians:

—normalized remuneration per physician: Normalized, Canadian family physicians (general practitioners / GPs) are at the 69th percent rank among family physicians in OECD member countries; specialist physicians are at the 79th percent rank.4

—physicians per 1,000 population: In 2021, the OECD average ratio of practising physicians per 1,000 population was 3.6; Canada’s ratio was well below the average, at 2.8. The Canadian physician density statistic needs qualification. The Canadian distribution of practising physicians differs significantly from the OECD average: the Canadian family physician ratio (47 percent) is well above the OECD GP average (23 percent); the Canadian specialist rate (53 percent) is below the comparable OECD average (64 percent).5 Canada’s percent rank among OECD countries rose modestly (from 13th in 2000 to 17th in 2021).6

—ratio of urban-to-rural physician density: In all countries, the ratio of physicians per 1,000 population is higher in urban than in rural regions. The OECD average urban/rural ratio is 1.6/1.0; Canada’s ratio is, at 2.8/1.0, much higher (OECD 2021).

The following section discusses the implications of generational change in the medical profession. The third section makes the case for a large increase of nurse practitioners’ share in the delivery of primary care, and promotion of per capita remuneration to encourage multi-discipline primary care.

Generational Changes among Canadian Physicians

Drawing on data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and the National Physician Health Survey of the Canadian Medical Association, Lee and colleagues (2021) concluded that physicians are reducing average hours worked while maintaining constant remuneration:

In a more recent article, Kralj et al. (2024) found that physician weekly working hours declined from the 1987–91 average, 52.8, to the 2017–21 average, 45.9, a decline of 9 percent. Most of the decline took place among male physicians. Female physicians’ hours remained approximately constant at 46 hours; male physicians’ hours declined from approximately 54 to 48 hours. Over the years 2008 to 2019, the number of annual services per family physician services fell from about 6,500 to 5,000. Over the same years, the number of annual services per specialist modestly rose from 4,000 to 4,500, but ultimately returned to 4,000 (Lee et al. 2021).

There are many factors underlying the decline in average hours worked (Grudniewicz et al. 2023). One of them is a desire for a better life/work balance – so-called “feminization” of the profession has probably contributed to the reduction in average work hours, albeit, men reduced their hours worked more than women (Lee et al. 2021). Female physicians will soon be in the majority. Among physicians above age 50 the majority are male; below age 50, the majority are already female (CIHI 2023c). The desire for lower hours per week is perfectly legitimate. While average weekly hours of work declined post-1990, inflation-adjusted annual remuneration remained stable in the 1990s, rose in the first decade of this century, and remained stable in the second decade (Kralj et al. 2024, Figure 3). The combination over the last three decades of reduced weekly hours and an increase in inflation-adjusted remuneration is further evidence of the influence exercised by physicians’ associations.7

What’s to be done? A caveat. The essence of a professional – whether in the context of healthcare delivery, the judiciary, or education institutions – is a lengthy investment in acquiring relevant knowledge, thereby enabling services that beneficiaries cannot be expected to provide for themselves. To undertake their contribution to healthcare, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, etc., need considerable independence. On the other hand, the provinces have the constitutional authority to “steer” the health system as they see best and determine the necessary budgetary allocation.8 There is no permanent ideal balance between professional independence and provincial financial authority.

Reform Options

Expanding Employment of NPs in Ambulatory Multi-discipline Clinics

The International Council of Nurses (2020) provides this summary guideline for a nurse qualifying to be a nurse practitioner:

A NP is an Advanced Practice Nurse who integrates clinical skills associated with nursing and medicine in order to assess, diagnose and manage patients in primary healthcare (PHC) settings and acute care populations as well as ongoing care for populations with chronic illness (p.6.).

In Canada, the provinces have jurisdiction over professional certification, and they take responsibility for defining what physicians and NPs can and cannot do in the respective province. Table A1 in online Appendix A summarizes the scope of NPs across provinces and territories as of 2020. There are some differences in NP scope among provinces but, in all provinces, NPs can undertake the great majority of the 38 listed interventions. In the northern territories, there is no NP limit on any of the 38 interventions. The conclusion: scope of practice is not an impediment to hiring NPs.

In addition to the ranking of physicians’ density and remuneration in Canada relative to other OECD countries, another indication of physician influence is the urgency among provincial health ministries to accelerate training of family physicians.9 There is no analogous urgency in training of more NPs.

Rigorous comparisons, conducted to compare the quality of services by NPs relative to services by physicians, have consistently concluded that NPs provide services as good as those provided by physicians (Horrocks et al. 2002; Martin-Misener et al. 2015; Maier et al. 2017; Buerhaus 2018). As an example, see Box 3 for the abstract from Martin-Misener’s randomized control evaluation, published in the British Medical Journal.

On the assumption that NPs perform as many services as would a family physician, a crude estimate of the cost to a provincial treasury for training and remunerating a NP is probably half that of a family physician. Before the education required to become a NP, many NPs have clinical experience as a registered nurse (RN). Their incremental education does not require more medical colleges. Admittedly, to the cost of incremental NP education should be added education cost in RN training. In 2020/21, the average net earnings of a family physician in Canada was about $230,000. The 2022 NP net earnings in BC ranged from $170,000–$187,000.

Over the last decade, the employment of NPs across Canada has obviously increased. The province that has most consistently promoted NP employment is Ontario (see Figure 2). The NP densities in Ontario, the northern territories, plus small population provinces are approximately double the densities in Quebec, Alberta, and BC.

In addition to obstacles posed by physicians’ associations, nurses’ unions are not the most vocal voices in advancing the potential of NPs as professionals working in a manner similar to that of family physicians. Nurses’ unions are primarily concerned with collective bargaining in the context of hospitals and other large institutions. The majority of NPs work in such institutions, as opposed to delivery of care in primary care teams, which are usually much smaller institutions.10 Admittedly, nurses’ unions do support a much-expanded role for NPs. In a survey conducted by the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions (2018, p.24), three conclusions were highlighted:

—Various barriers (federal/provincial/territorial legislation and regulation, lack of role clarity, employer policies, etc.) prevent NPs from working to their full scope of practice.

—More than a quarter of NPs report not working to the full scope of practice, leading to job dissatisfaction.

—Lack of role clarity contributes to the suboptimal utilization of NPs in the system.

Promotion of Multi-discipline Primary Care Clinics

Ideally, multi-discipline primary care clinics will become the norm. At present, they are still a minority, even in Ontario, the province that has most aggressively proposed alternatives to traditional physician-controlled fee-for-service (FFS) clinics (Blomqvist and Wyonch 2019). The incentives – rostering patients and remunerating by capitation or enhanced FFS – have modestly reduced total per patient costs relative to traditional FFS clinics (Glazier et al. 2015; Laberge et al. 2017). The direct cost of multi-discipline primary care is on average higher than in FFS clinics. Including specialist referrals and hospitalization, however, the total cost per patient in most of the Ontario’s alternatives is below traditional FFS clinics, due to fewer referrals and hospitalization.

Probably, an important constraint on adoption of multi-discipline clinics is their administrative complexity relative to traditional FFS physician-controlled clinics. Ndateba et al. (2023) report superior quality of patient service, relative to physician-controlled clinics, in collegial, well-managed multi-discipline clinics. However, what if the multi-discipline clinics are not well managed? Relative to managers of physician-controlled clinics, managers of multi-discipline clinics have a more complex task. They manage more than one profession and they have more complex billing and remuneration formulas with the relevant provincial health ministry. They also have the task of imputing overhead costs to various professionals in the clinic.

Conclusion

There are many institutional reforms to consider, but two, I argue, are imperative. The first is an aggressive provincial expansion of NPs. I advocate this instead of just increasing the number of medical colleges in Canadian universities, and relying on immigration among physicians from developing countries. The second suggested reform is, as in Ontario, the active promotion of primary care delivery via multi-disciplinary clinics, which incorporate NPs among other professionals.

References

Alberta. 2024. “Nurse Practitioners to Help Strengthen Primary Care: A New Program will Support Nurse Practitioners to Work Independently and Provide Albertans with More Access to Primary Care Clinics.” Ministry of Health. Accessed 20240424 at https://www.alberta.ca/release.cfm?xID=90226DB559D7D-D56B-7219-70930C28213A9D8C

Angus Reid. 2022. “Access to Health Care: Free, but for all? Nearly nine million Canadians report chronic difficulty getting help.” Accessed 20231002 at https://angusreid.org/canada-health-care-issues/

Blomqvist, A., and R. Wyonch. 2019. Health Teams and Primary Care Reform in Ontario: Staying the Course. Commentary 551. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

British Columbia. 2018a. “B.C. Government’s Primary Health-care Strategy Focuses on Faster, Team-based Care.” Accessed 20240324 at https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2018PREM0034-001010

_______. 2018b. “Backgrounder – Contracting 200 NPs into Primary Care Networks.” Accessed 20240325 at https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=BACKGROUNDER+%E2%80%93+CONTRACTING+200+NPs+INTO+PRIMARY+CARE+NETWORKS

_______. 2019. “Primary Care Networks – GP and NP Contracts and Compensation.” Accessed 20240328 at https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=Primary+Care+Networks+%E2%80%93+GP+and+NP+Contracts+and+Compensation

_______ 2022. “Appendix 3, Payment. Primary Care NP Contract.” Available from the author on request.

Buerhaus, P. 2018. “NPs: a Solution to America’s Primary Care Crisis.” American Enterprise Institute.

Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions (CFNU). 2018. “Fulfilling Nurse Practitioners Unfilled Potential in Canada’s Health Care System: Results from the pan-Canadian Retention and Recruitment Study.”

CBC. 2024. “Murky Rules for Nurse Practitioners Give Rise to Private Clinics in Ontario.” March 1. Available at https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-nurse-practitioner-private-clinics-1.7127951

Canadian Information for Health Information (CIHI). 2020. “Nurse practitioner scopes of practice in Canada, 2020” – data table.

_______. 2023b. “Physician payment indicators.”

_______. 2023c. “Physicians supply 2011-21.”

_______ 2024. “Nursing in Canada, 2014-2023” – data tables.

Commonwealth Fund. 2022. Stressed Out and Burned Out: The Global Primary Care Crisis. Available at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/nov/stressed-out-burned-out-2022-international-survey-primary-care-physicians

Glazier, R., B. Hutchison, and A. Kopp. 2015. Comparison of Family Health Teams to Other Ontario Primary Care Models. Institute for Clinical Evaluation Sciences.

Grudniewicz, A., E. Randall, M. Lavergne, E. Marshall, L. Jones, D. Rudoler, K. Horrey, M. Mathews, M. McKay, G. Mitra, I. Scott, D. Snadden, S. Wong, and L. Goldsmith. 2023. “Factors Influencing Practice Choices of Early-career Family Physicians in Canada: a Qualitative Interview Study.” BMJ Open, 2023:21:84.

Horrocks, S., E. Anderson, and C. Salisbury. 2002. “Systemic Review of Whether NPs Working in Primary Care can Provide Equivalent Care to Doctors.” British Medical Journal 324: 819-823.

International Council of Nurses. 2020. Guidelines on Advanced Practice Nursing, 2020.

Kralj, B., R. Islam, and A. Sweetman. 2024. “Long-term Trends in the Work Hours of Physicians in Canada.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 196(11).

Laberge, M., W.P. Wodchis, J. Barnsley, and A. Laporte. 2017. “Costs of Health Care across Primary Care Models in Ontario.” BMC Health Services Research 17:511.

LaPorte, A. 2018. “Physician Service Costs: Is There Blame to Share Around?” in Marchildon, G., M. Sherar (eds.). Healthcare Papers: New Models for the New Healthcare. Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Lee, S., S. Mahl, and B. Rowe. 2021. “The Induced Productivity Decline Hypothesis: More Physicians, Higher Compensation and Fewer Services.” Health Care Policy, 17(2):90-104.

Lindbeck, A. 1995. “Hazardous Welfare State Dynamics.” American Economic Review. Papers and Proceedings, May. 85: 9–15.

Maier, C., L. Aiken, and R. Busse. 2017. “Nurses in Advanced Roles in Primary Care: Policy Levers for Implementation.” OECD Health Working Papers, no. 98.

Manns, B., M. Tonelli, J. Zhang, D. Campbell, P. Sargiouis, B, Ayyalasomayajula, F. Flement, J. Johnson, A. Laupacis, R. Lewanczuk, and K. McBrien. 2012. “Enrolment in Primary Care Networks: Impact on Outcomes and Processes of Care for Patients with Diabetes.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 184(2): E144:E152.

Martin-Misener, R., P. Harbman, F. Donald, K. Reid, K. Kilpatrick, N. Carter, D. Bryant-Lukosius, S. Kaasalainen, D. Marshall, R. Charbonneau-Smith, and A. CiCenso. 2015. “Cost-effectiveness of NPs in Primary and Specialised Ambulatory Care: Systematic Review.” BMJ Open.

Ndateba, I., S. Wong, J. Beaumier, F. Burge, R. Martin-Misener, W. Hogg, W. Wodchis, K. McGrail, and S. Johnston. 2022. “Primary Care Practice Characteristics Associated with Team Functioning in Primary Care Settings in Canada: a Practice-based Cross-sectional Survey.” Journal of Interprofessional Care.

Organisation for Economic and Cooperation Development (OECD). 2021. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD indicators.

_______ 2023. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD indicators.

Our World in Data. 2023. Coronavirus cases. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

Pettigrew, L., S. Kumpunen, and N. Mays. 2020. “Primary Care Networks: the Impact of Covid-19 and the Challenges Ahead.” British Medical Journal, 370:m3353.

Québec. 2024. Transformation du système de santé et de services sociaux. Available at at https://www.quebec.ca/sante/systeme-et-services-de-sante/organisation-des-services/systeme-quebecois-de-sante-et-de-services-sociaux/transformation-systeme-sante/reseau-sante-efficace-population

Zhang, Tingting. 2024. The Doctor Dilemma: Improving Primary Care Access in Canada. Commentary 660. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

- 1 Cumulatively to December 2023, the Canadian ratio of COVID cases per 1,000,000 is 123,000, the average ratio in high-income countries, 341,000 (Our World in Data 2023).

- 2 Based on purchasing power parity in 2022, Canada spent US$6,349 per capita on (private plus public) health services; the OECD average was US$4,986. In terms of share of GDP, Canada spent 11.2 percent of GDP on health services, whereas the OECD average was 9.2 percent.

- 3 In December 2023, the Quebec National Assembly approved Bill 15 (An Act to make the health and social services system more effective). The rationale is to create regional and local state entities able to provide more effective services (Québec 2024). It is too early to know whether this reform of “upstream” administration solves problems of inadequate access to services.

- 4 The OECD normalizes national physician remuneration by determining the national average physician earning relative to the average national wage. The percentile rank is the percent of OECD member countries whose normalized physician incomes are below the Canadian rank. In other words, two-thirds of countries provide lower normalized family physician remuneration than does Canada; four-fifths of countries provide lower normalized specialist remuneration than Canada. There are 38 OECD member countries. Not all provide the relevant data. The number in the various health statistics dimensions ranges from 25–35.

- 5 The OECD categorizes that, on average, 13 percent of physicians work in hospitals, as managers, educators, etc. The OECD acknowledges national differences in categorizing GPs, specialists, and “other.” Zhang (2024) specifies a target ratio and illustrates the under-supply of family physicians by province.

- 6 Canada’s ratio of physicians per 1,000 population rose from 2.0 in 2000 to 2.8 in 2021; the OECD average rose from 3.2 to 3.6.

- 7 The earliest year for which CIHI (2023b) provides average family and specialist physician incomes is 2014/15. The 2014/15 gross earning averages are respectively $318,000 and $437,000. The 2020/21 averages are $346,000 and $465,000. Adjusting for inflation over the six years, the real values were effectively stable (OECD, 2023, Figure 8.12). In a physician-owned clinic, the overhead cost per physician is approximately one-third of gross earnings. Under these assumptions, net 2020/21 family physician average income was $230,000.

- 8 In Canada, universal single-payer medical insurance was introduced, first in Saskatchewan, in 1962. By 1970, all provinces had introduced similar insurance models. In 1984, Ottawa legislated five principles that all provinces must respect: 1) universal insurance coverage for all residents in Canada; 2) comprehensive coverage of all medically necessary services; 3) reasonable accessibility for all Canadian residents with no patient payment at point of service; 4) portability of insurance across provinces; 5) public administration of insurance. An important court constraint is Chaoulli, which constrained provincial government waiting lists.

- 9 Currently, four universities are building new medical colleges: Simon Fraser University, York University, Toronto Metropolitan University, and University of Prince Edward Island.

- 10 In Canada in 2022, 39 percent of NPs worked in community clinics, 38 percent in hospitals, 4 percent in nursing homes, other sites not stated (CIHI 2023).