The Study In Brief

In Canada, most government cash benefit payments require recipients to file a tax return. Individuals who fail to participate in the tax system, often the most vulnerable in society, may forgo important government benefits (or even entitlements to government services when such services are tied to tax return information). The September 2020 Speech from the Throne committed the federal government to “work to introduce free, automatic tax filing for simple returns to ensure citizens receive the benefits they need.”

This Commentary first describes various levels of possible filing automation. First of all, some countries do not require tax filing at all for people in simple tax situations, particularly employees for whom tax withheld at source by the employer and remitted to the tax authority is adjusted throughout the year such that the total amount withheld at the end of the year corresponds to the exact tax liability. Individuals facing a more complicated tax situation, or eligible for additional tax relief, must often file a tax return. In other countries, particularly in Scandinavia, tax filing is quasi-automatic: eligible taxpayers with basic sources of income receive prepopulated tax forms with their tax liabilities already computed by the tax authority; taxpayers need only verify the prefilled information for accuracy.

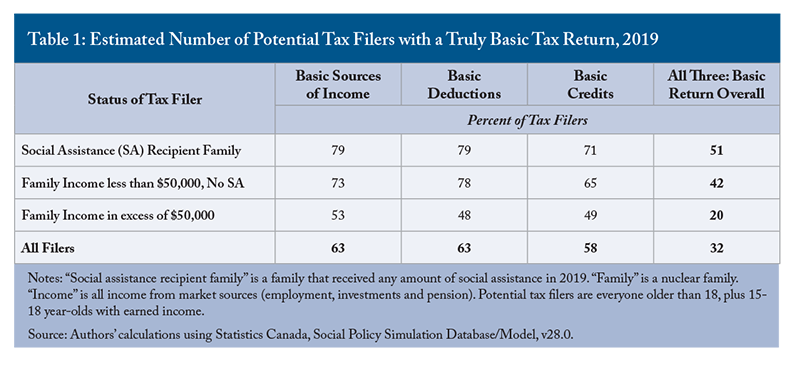

The completeness of prepopulated tax forms and the accuracy of computations prefilled by the tax authorities depend on the complexity of filers’ tax situations. The greater the number of taxpayers with basic tax returns, the more practical it would be to fully automate tax filing. Provided the Canada Revenue Agency obtains reliable basic personal information on tax filers, we estimate that only one in three potential tax filers would have a “basic” tax return – i.e., a tax return for which the CRA would already receive sufficient information from third parties to accurately compute taxes and benefits.

Therefore, we argue that the Canadian tax code contains too many deductions and credits recognizing specific personal circumstances, expenses, or activities to make a widely available, fully automatic filing system practical. On balance, the current self-assessment with Auto-Fill by the CRA is well adapted to Canada’s complex tax system, and making it more automatic would require a fundamental simplification of the underlying tax system.

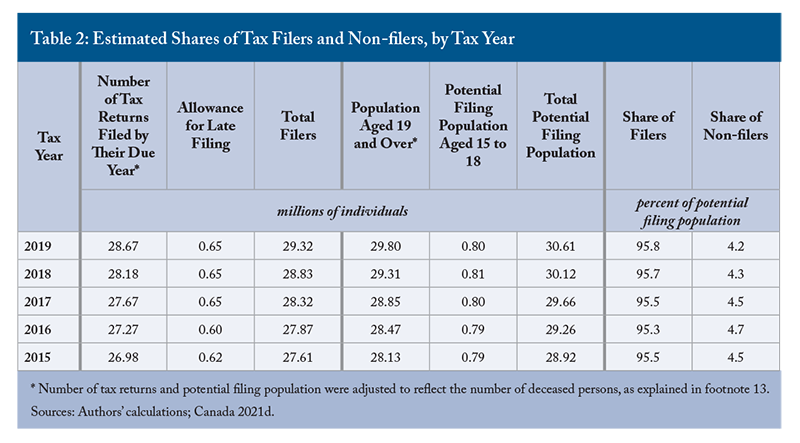

The Commentary concludes that fully automatic filing for all is a blunt instrument to get to the narrower problem of non-filing eligible benefit recipients. We estimate that about 4.2 percent of potential tax filers – or more than 1 million people – do not participate in the tax system, but likely should. More targeted strategies to reach these people are preferable, such as decoupling the requirement to file a tax return from eligibility to receive benefits. Despite practical challenges, establishing a new body specifically tasked with delivering income-tested benefits to Canadians could make this possible, better serving the poverty-reduction objectives of government support programs that are now tied to tax filing.

Canada’s federal and provincial governments increasingly use cash benefits to families as a mean to achieve their redistribution goals, including poverty reduction.

Many benefits require recipients to file a tax return to be eligible – the cash transfer system is intertwined with the tax system. Individuals who do not participate in the tax system, often the most vulnerable in society, could forgo important government benefits or entitlements to government services.

The September 2020 Speech from the Throne committed the federal government to “work to introduce free, automatic tax filing for simple returns to ensure citizens receive the benefits they need.” It is not clear what automatic filing actually would mean in practice, although it seems to imply an automated process through which taxpayers would have their tax return filled and filed by the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) in the case of federal and provincial/territorial personal income taxes, except in Quebec, where provincial taxes are administered by Revenu Québec. For many taxpayers, having the tax authority’s automated systems fill out their tax return and compute their tax liabilities on their behalf for free is certainly an appealing idea.

In this Commentary, we review Canada’s current tax-filing practices and look at various tax-filing systems around the world. Based on this review, we suggest what automatic tax filing might look like in Canada, and examine potential rewards and challenges.

We present an estimate of the number of people who do not participate in the tax system but likely should, and sketch some of the factors and difficulties explaining their non-filing behaviour. We also discuss the complexity of the tax code, and estimate how many taxpayers truly have a basic federal tax return that easily could be fully automated.

We argue that making fully automated and automatic tax filing broadly available in Canada is challenged by the complexity of the tax code. The tax system is widely used to achieve social and economic goals, and a number of provisions would be difficult to automate. Governments’ appetites to use new tax concessions for their redistributive goals are on the rise, making fundamental tax reform aimed at tax simplification unlikely.

We conclude that automatic filing for all would be a sweeping solution to the narrower problem of getting benefits to eligible recipients who do not file a tax return. More targeted strategies to reach these people are preferable. We propose that decoupling the requirement to file a tax return from eligibility to receive benefits is worth serious consideration. Despite practical challenges, establishing a new body specifically tasked with delivering income-tested benefits to Canadians could make this possible, better serving the poverty-reduction objectives of government-support programs that are now tied to tax filing.

Tax Filing Obligations around the World

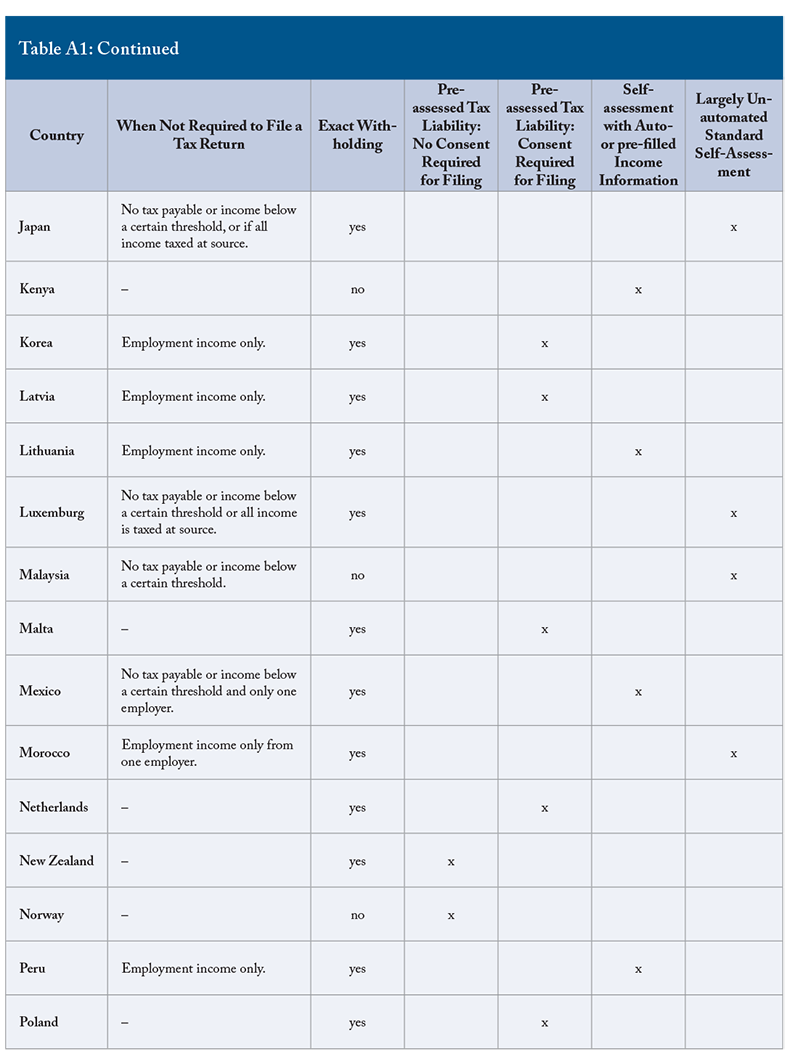

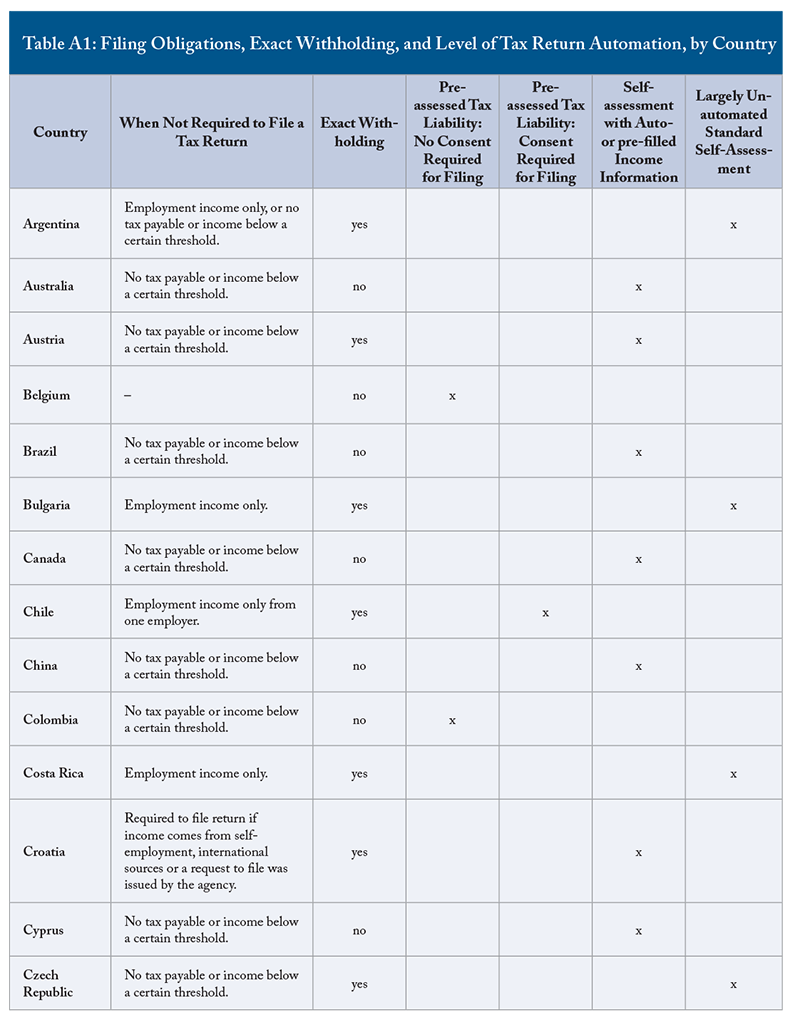

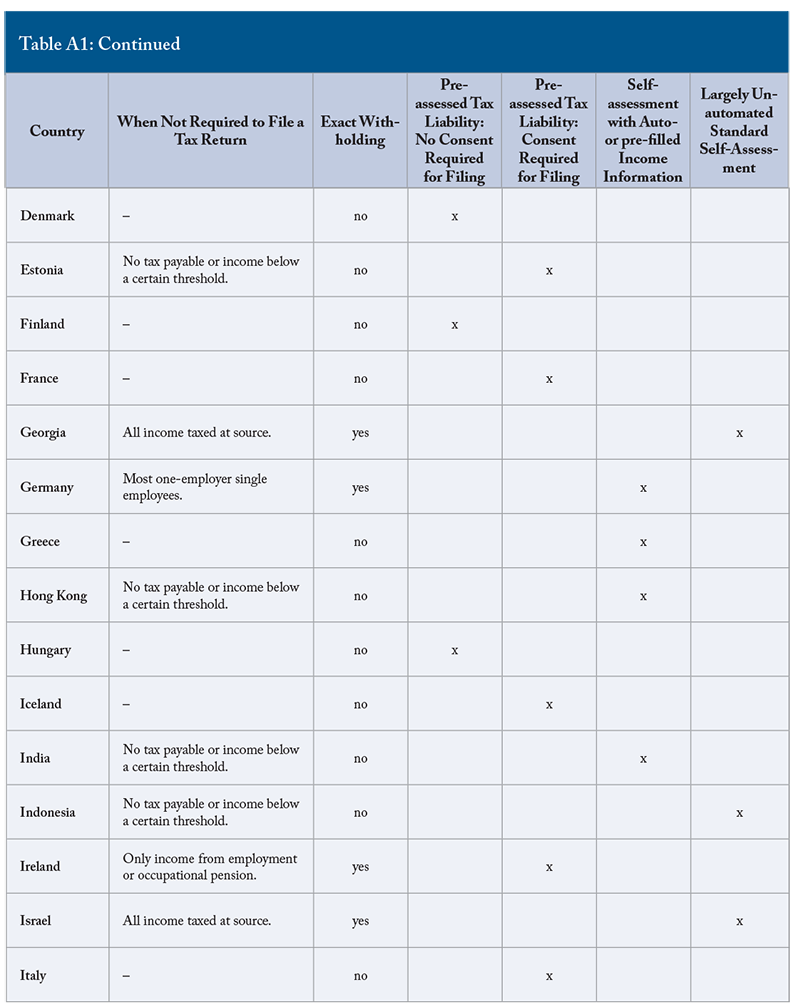

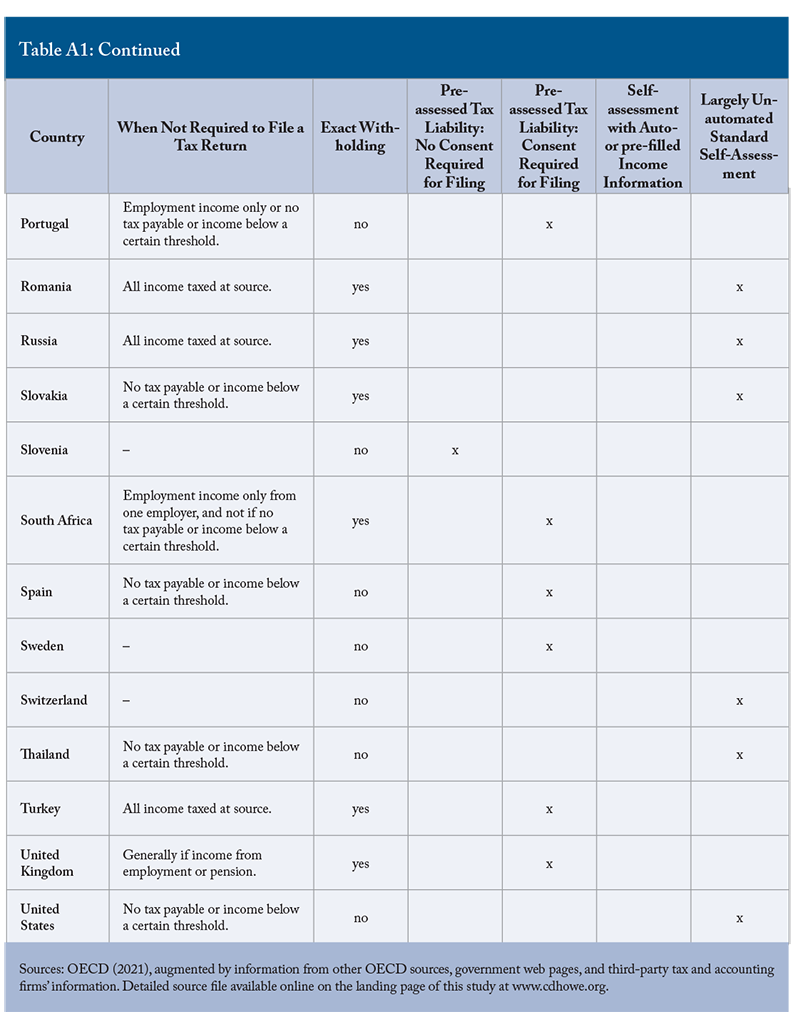

Many countries do not require everyone to file a tax return. In Canada, persons who have no tax payable for the year, no benefit repayments due, no capital gains and no self-employment income generally are not required to file a tax return for the year (Canada 2021c). Many other countries have similar requirements in that persons with no tax payable or income below a certain threshold are not required to file (see Appendix Table A.1).

By not filing, however, individuals forgo entitlements to refundable credits and cash benefits, such as the Canada Workers Benefit, the Guaranteed Income Supplement, the GST Credit and the Canada Child Benefit, and many other similar provincial programs, which can be worth from a few hundred dollars to thousands. As well, in Canada, many government-support programs related to subsidized housing, childcare, pharmacare and legal aid are income tested and rely at least partially on tax return information to assess eligibility. Income earners who do not file also forgo their refund of taxes withheld at source and remitted to the tax agency by their employers, financial institutions or benefit administrators. Where, as in Canada, tax withheld at source on each paycheque is just an approximation based on a simple annual extrapolation, lower-income earners in particular often are entitled to some refund of taxes when filing a return.

Some countries have more sophisticated tax-withholding systems in which the tax agency aims to withhold, for certain taxpayers in simple tax situations, the exact amount of tax payable throughout the year (see Appendix Table A.1). Some countries adjust tax withholdings cumulatively at regular pay intervals based on the evolution of prior earning, while others adjust the amount of tax withheld on the last paycheque so that total withholdings for the year correspond to actual tax payable (Tax Policy Center 2020). Exact withholding ensures that the taxpayer has paid enough taxes and that, for simple tax situations, no tax refunds will need to be issued.

In exact-withholding countries, the requirement to file generally depends upon the complexity of the taxpayer’s earning situation. For instance, individuals with more than one employer in the year, with self-employment income or some other non-wage sources of income still may be required to file. Employees in Argentina, Costa Rica, Chile, Germany, Ireland, Peru and the United Kingdom, to name a few countries, generally are not required to file a tax return if their only source of income is from employment (see Appendix Table A.1).

The ability to implement an exact-withholding system is greatly facilitated the simpler the tax code. Taxpayers who are not required to file a return usually face a simple tax-rate structure, be taxed uniquely based on their own situation independently of their spouse or dependents and generally be claiming only a small number of widely applicable deductions and credits (Tax Policy Center 2020). In the United Kingdom, for example, most employed people and pensioners are not required to file anything. For them, income is subject to a simple personal allowance and a tax-rate schedule, while only a few tax-relief provisions are available (United Kingdom 2021b).

An important consideration is that, even if eligible taxpayers are not required to file a return, they are still required to provide updated non-financial information – such as marital status, dependents or any other missing information necessary to compute taxes – to the tax authority or their employer. Another important consideration is that taxpayers who are not required to file a tax return generally still must file a claim if they wish to claim particular tax reliefs or benefits, because only basic tax provisions are considered for the purpose of calculating “exact” tax withholdings. For example, Irish taxpayers must complete a tax return to claim additional tax credits, reliefs or expenses (Irish Tax and Customs 2021). UK taxpayers must claim Child Benefit and Universal Credit (United Kingdom 2021a, 2021c). In Germany, many taxpayers for whom tax filing is not compulsory still may receive a tax refund if they file (Wundertax 2021).

Canada’s Tax-Filing System: A Snapshot

The Canada Revenue Agency – Revenu Québec operates similarly – provides a few options for filing a return, based on eligibility. Individual taxpayers can elect to file a return themselves, either through a hard-copy paper return or electronically, or they can authorize a representative – an accountant, a tax preparing firm or a volunteer – to file on their behalf.

People with modest income and a simple tax situation may use the free services of community volunteer tax clinics. In the 2019 tax season, the last tax season not affected by COVID-19 lockdowns, volunteers prepared 835,216 tax returns (Canada 2020c). Also, the CRA invites selected individuals with low or fixed income and with a simple tax situation to use its “File My Return” service, where individuals can file quickly for free over the phone without producing an actual tax return (Canada 2021f).

The CRA also operates a self-assessment regime with an optional “Auto-Fill” feature for those who complete their tax forms electronically. This service allows individuals and authorized tax-filing representatives who are using CRA-certified software to fill in sections of the return automatically with information the CRA receives from third parties on income, benefits and retirement savings contributions (among others). To use this service, individuals are required to register with CRA’s secure online portal “My Account,” which allows users to view and modify information regarding their tax information profile. For authorized representatives, a “Represent a Client” portal provides the same services, including the ability to use the Auto-Fill feature (Canada 2021a). Filers (or their representatives) can choose whether or not to use the information that is populated using Auto-Fill, and make amendments to the populated fields as necessary. In fiscal year 2018/19, Auto-Fill was used nearly 12 million times (Canada 2020c).

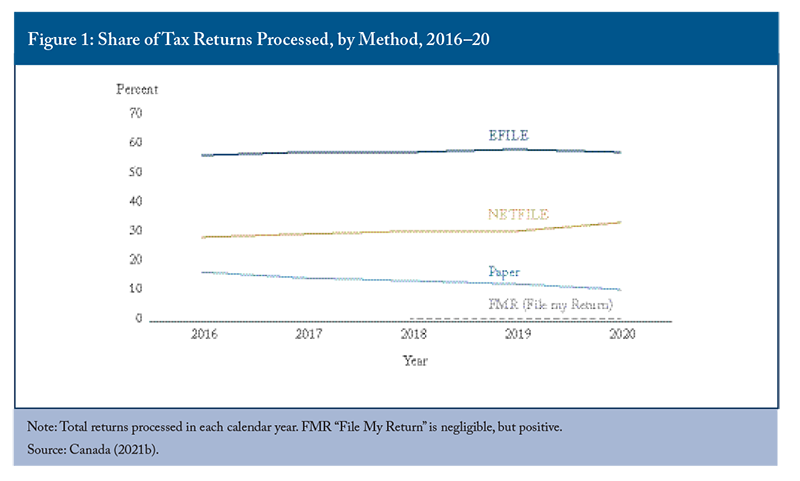

The CRA has two methods for the electronic filing of returns: EFILE and NETFILE. Electronic filing is available to most taxpayers, although some types of returns cannot be filed electronically. EFILE is used by authorized tax preparation service providers on behalf of their clients, while NETFILE is used by individual filers. Both use the same software (if compatible and certified) they used to prepare the return (Canada 2017). EFILE is the dominant filing method, with around 57 percent of returns filed in 2020 using this method with the help of a representative tax preparer (Figure 1). NETFILE’s popularity among tax filers is slowly increasing, representing 33 percent of all returns processed in 2020, up from 28 percent in 2016. The proportion of tax returns mailed to the CRA has been declining, from 16 percent of all returns processed in 2016 to 10 percent in 2020.

Finally, a negligible, but rising, number of low-income individuals use CRA’s “File My Return” (FMR) fully automated phone service: nearly 70,000 in 2020, up from 47,000 in 2016. FMR suffers, however, from very low enrolment. For instance, in 2019, the CRA invited 542,008 individuals on social assistance to use FMR, but only 8 percent did so (Canada 2020c). We do not know the total number of FMR invitations sent in 2020, but assuming the number is similar to that of 2018 (970,000), the total take-up rate of FMR would be around 7 percent.

Tax Filing Automation: International Experience

As already mentioned, countries that have adopted exact-withholding systems generally exempt many taxpayers (commonly those in simple tax situations) from filing a tax return. For these taxpayers, not filing taxes at all means that the tax system is as automated and automatic as could be.

For taxpayers in tax situations requiring them to file, or for taxpayers in countries like Canada with no exact-withholding system where they are generally required to file a return, “automatic filing” means a variety of automated mechanisms to simplify greatly the process of annual tax filing. In the most straightforward and complete procedure, the tax authority would compute and file taxpayers’ annual returns automatically. No countries provide such a high degree of automation for all tax filers, but some come very close for most taxpayers.

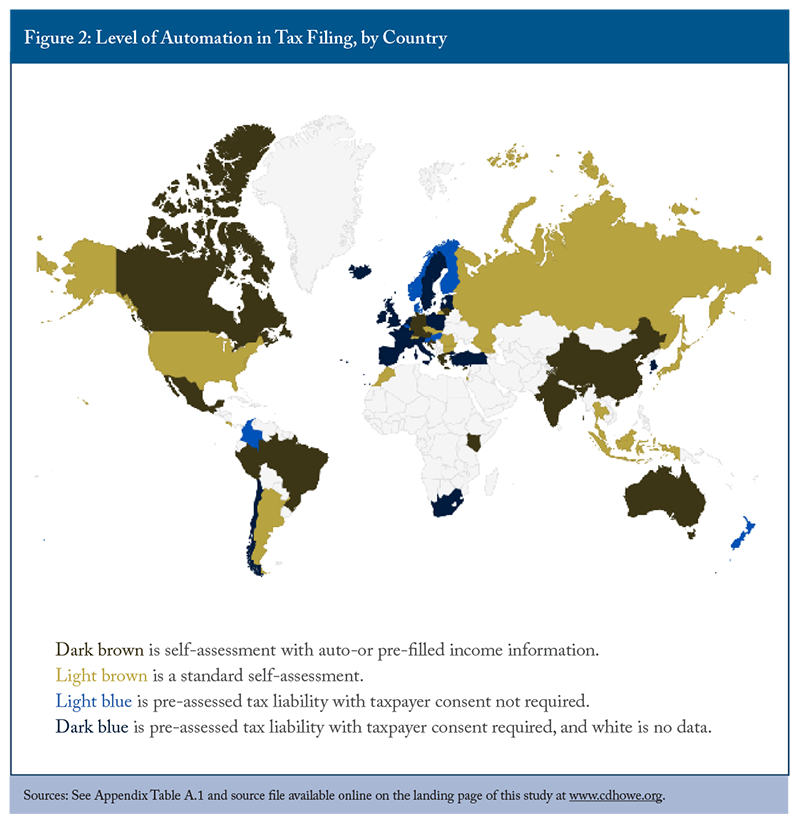

An overview of the filing obligation, exact withholding and level of automation for personal income tax in 57 countries is provided in Appendix Table A.1.We based our evaluation on the countries presented in the OECD’s 2021 survey of tax administrations (OECD 2021), augmented by information from other OECD sources, government web pages, and third-party tax and accounting firms’ information. We placed the level of automation in these countries into four broad categories:

- level 1 automation: prepopulated tax returns by the tax agency with preliminary assessment of tax liability deemed accepted if the tax filer submits no modifications – that is, the taxpayer’s consent to file is not required;

- level 2 automation: prepopulated tax returns with preliminary assessment of tax liability requiring taxpayer’s expressed consent to file;

- level 3 automation: self-assessment of tax liability with some income information auto- or pre-filled by the tax agency; and

- level 4 automation: largely unautomated standard self-assessment.

Figure 2 shows the level of automation in the examined countries. Automated systems where filers are presented with a preliminary assessment of tax liability are largely concentrated in western and northern Europe while the rest of the world typically relies on self-assessment regimes, many of which provide auto- or pre-filled income data by the tax authority.

Level 1 Automation: Pre-assessed Tax Liability, Taxpayer Consent Not Required

In some countries, the tax agency populates the taxpayer’s personal income tax return with basic information provided by third-party organizations such as employers and financial institutions. The tax agency then uses this information to compute a preliminary tax liability assessment. The prepopulated return is delivered to the taxpayer for review and, if needed, adjustments. These tax-filing regimes are generally described as tax agency reconciliation systems (Tax Policy Center 2020). They differ in terms of non-mandatory and mandatory acceptance by the taxpayer.

Non-mandatory acceptance of the tax agency’s preliminary tax assessment is the closest tax-filing regime to being fully automatic. In this regime, the tax authority prepares most tax returns and delivers them to taxpayers either by hard copy or, more frequently, by electronic filing systems (OECD 2021). Taxpayers then review their returns for errors and/or omissions. Taxpayers who change or add information to the prepopulated tax return are required to resubmit the return to the tax agency. If there are no errors or omissions, the taxpayer is not required to have further correspondence with the tax agency; after the deadline to submit returns expires, the agency assumes or “deems” the return to be accepted by the taxpayer (OECD 2021).

Only 8 of the 57 countries in Appendix Table A.1, mostly found in Europe, use this tax-filing system for many of their taxpayers (not all taxpayers qualify). In Finland, Slovenia and Denmark (the pioneer of this system), for example, most taxpayers file their tax returns under a non-mandatory acceptance regime (OECD 2019). Not requiring taxpayers to confirm the accuracy of prepopulated tax assessments means that, for those taxpayers, the enterprise of filing tax returns is as close to automatic as can be observed in the real world.

Level 2 Automation: Pre-assessed Tax Liability, Taxpayer Consent Required for Filing

Systems requiring the consent of taxpayers for filing share many characteristics with systems with non-mandatory acceptance. In both, the tax agency prepopulates selected returns and provides a preliminary tax liability assessment for the taxpayer’s review and corrections, if needed. In mandatory systems, however, the taxpayer must submit, or accept, the preliminary tax assessment even if no corrections are needed (OECD 2021). This regime is used in 17 of the 57 countries examined in Appendix Table A.1, including, most recently, South Africa. Almost half of personal income tax returns in France and Spain are filed under this prepopulated-with-confirmation method; in Chile, the share is over 80 percent (OECD 2019). This system is not fully automatic, since the taxpayer is required to submit a tax return to the agency, corrected or not, but it is automated in that the tax authority completes a preliminary tax assessment.

Level 3 Automation: Self-Assessment with Auto- or Pre-filled Income Information

In self-assessment regimes, taxpayers are responsible for filling out tax forms with their personal and financial information, calculating their tax liability and submitting their return to the tax agency. Tax agencies may still collect information (and withhold taxes) from third parties such as financial institutions and employers. Furthermore, some tax authorities use the information they have on file to facilitate the preparation of tax returns. In Canada, for example, the CRA uses the Auto-Fill feature on compatible tax-filing software. Income and other tax-related data on file with the CRA are automatically imported from the CRA’s online secure servers and filled in the tax return at the filer’s (or tax preparer’s) request. Taxpayers retain full discretion on whether or not to use the Auto-Fill feature and assess their return “from scratch” and make changes if necessary.

This self-assessment regime is found in 15 of the 57 countries reviewed in Appendix Table A.1. The data that can be pre-filled, or auto generated, into a tax return vary from country to country. In Canada and Lithuania, for example, a wide variety of financial and income information is included. Although this system fills in income data automatically, the taxpayer is still responsible for ensuring that the tax return is complete, correct, self-assessed and filed to the tax authority.

Level 4 Automation: Largely Unautomated Self-Assessment

Finally, the least automated tax-filing regime is the largely unassisted standard self-assessment. Under this regime, taxpayers do not have access to pre-filled or automatically filled data from the tax agency. Instead, they are generally required to fill in all relevant tax information from employers and financial institutions, calculate their tax liability and submit their return to the tax agency (either in digital or hard-copy form). This is the case in the United States,

Automatic Tax Filing in Canada: Risks, Rewards and Challenges

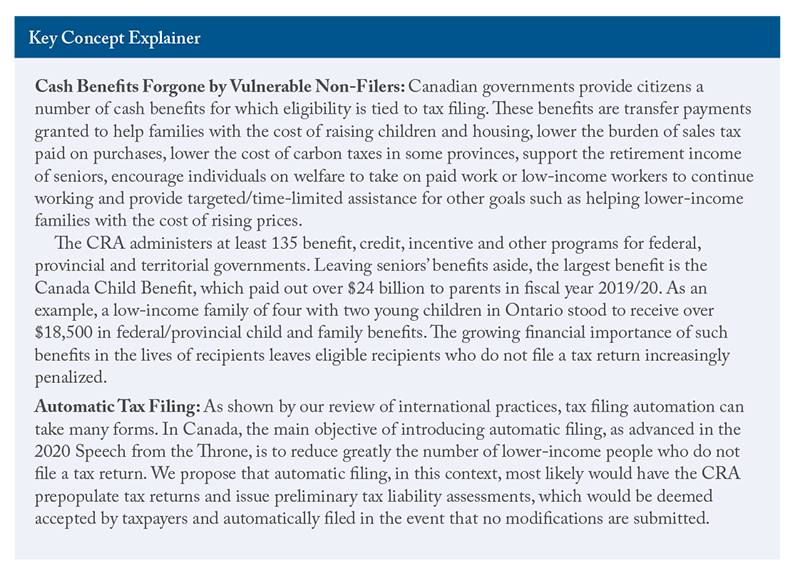

In Canada, the main objective of introducing automatic filing, as advanced in the 2020 Speech from the Throne, is to reduce greatly the number of lower-income people who do not file a tax return. Automatic filing in this context most likely would have the CRA prepopulate data in tax returns and issue preliminary tax liability assessments, which would be deemed accepted by taxpayers and automatically filed in the event that no modifications are submitted.

Tax Complexity: A Major Challenge

Complying with the tax system costs time, effort and money. Most filers use tax-preparation service providers. For others, tax preparation software packages can digest most of the tax complexity by guiding filers in the preparation of their returns. Still, the need for tax advice and to keep proper documentation to take advantage of various tax provisions adds to compliance costs. Vaillancourt, Roy-César, and Barros (2013) estimated that, in 2011, the total costs of complying with personal income tax provisions – the value of time spent, money spent and costs of appeals – ranged between $4.6 billion and $6.7 billion.

The appeal of automatic tax returns is easy to understand. Letting the CRA’s “…computers fill out the [tax] forms and do the math on [tax filers’] behalf for free” (Trichur 2020) would save filers valuable time and money. This argument is largely speculative, however, because it ignores tax complexity. Compliance costs are first and foremost a function of the complexity and number of provisions in the tax system. Vaillancourt, Roy, and Lammam (2015, p.1) calculated that, “between 1990 and 2014, the text area occupied by the [federal] Income Tax Act and regulations increased 62%.” In addition, the number of federal personal income tax preferences (such as credits, deductions and benefits) measured in federal tax expenditures reports increased from 105 in 1991 to 143 in 2021.

Tax complexity could be a major hurdle to making automatic filing widely available. The 2020 Speech from the Throne recognized that reality by stating that automatic filing would be introduced for “simple returns.” In its purest form, a simple return would be a tax return for which the CRA has all the required information on file to enable the automatic and accurate assessment of taxes and benefits. A natural question to ask is how many filers present the characteristics of a simple (or basic) federal tax return?

Estimating the Number of Filers with a Truly Basic Tax Return

A simple or “basic return” is a tax return for which the CRA acquires, through third-party reports, all of the information required to enable it to compute straightforwardly an automatic and accurate assessment of taxes and benefits.

To facilitate automatic filing, we additionally assume that the CRA would have a satisfactory and reliable process in place through which it would obtain up-to-date basic information on tax filers, such as their contact information, dwelling, household composition, marital status and names of spouse and children. This is entirely doable given that the CRA already receives some of this information. All countries with automated filing systems have such systems in place – it is never entirely automatic. This information can be communicated to the tax agency in various ways – for example, directly by filers or indirectly by employers and other third parties. The point is that basic information on personal and living contexts would be needed for the CRA to implement reliable automated tax and benefit computations. For instance, information on a filer’s spouse is necessary to calculate benefits based on family income, such as the GST Credit, and other tax provisions, such as the spousal amount. In Quebec, the Solidarity Tax Credit includes an extra amount to persons living alone, so Revenu Québec requires additional information on household composition.

Statistics Canada’s SPSD/M database is built by combining administrative data from personal income tax returns with survey data on family incomes and expenditure patterns. The database is detailed and statistically representative of the Canadian population, including individual characteristics such as income received from various sources, living arrangements and family contexts. The associated sophisticated tax model allows us to micro-simulate complex personal income tax returns and benefit payments.

We separated our investigation into three components. Tax filers with “basic sources of income” are those (or their spouse) who do not receive income from any sources missing from third-party reporting. Tax filers with “basic deductions” are those who would not claim federal deductions for which some or all of the required information is not currently available to the CRA. Tax filers with “basic credits” are those who would not claim tax credits for which some or all of the required eligibility information is not currently available to the CRA.

We began our determination of the number of filers with a truly basic tax return by investigating sources of taxable income. Canada’s third-party reporting is reasonably comprehensive and covers most sources of income (Petit et al. 2021). The CRA will have on file employment income information submitted by employers, as well as amounts received for provincial social assistance benefits, employment insurance, private and public pension income, most dividend and interest income received and government benefits. Missing from the third-party reporting system will be mainly self-employment income, rental income, most taxable capital gains, net income received from a foreign country and spousal support payments received. On that basis, using the SPSD/M, we estimate the CRA would have the necessary annual income information on a filer, and the filer’s spouse, to accurately fill the tax return of 63 percent of potential filers in a given year (“Basic Income Sources” in Table 1).

But the tax system is complex and requires more than simply income information. Some information to compute material deductions to taxable income is not available to the CRA. For instance, parents can deduct childcare expenses, ex-spouses can deduct amounts paid in alimony, those relocating for work may be able to deduct moving expenses, members of the clergy can claim a deduction for their residence, and small business owners, farmers and fishing operators may claim a deduction against capital gains arising from the disposition of certain properties. Some employment expenses may be deducted. And there are a number of investment-related deductions for eligible losses, carrying charges or legal and accounting fees. On the basis of the tax deductions listed here alone for which the CRA needs additional information, using the SPSD/M, we estimate that the CRA would have sufficient information on file to fill, automatically and accurately, the tax returns of about 63 percent of potential filers (“Basic Deductions” in Table 1).

Then there is a multitude of tax credits recognizing personal circumstances, and for which the CRA needs inputs from claimants. The list is long. Examples include tax credits recognizing medical expenses, disability, purchasing a home, volunteer firefighting, donating to a charity, contributing to a political party, caregiving to relatives with a physical or mental impairment, occupational training, school teaching supplies, purchasing of new buildings or equipment to be used in activities such as farming, fishing, logging or construction, investing in a labour-sponsored fund and paying taxes in a foreign country. Other tax credits, such as for education and tuition fees, can be either carried forward for future personal use or transferred to a spouse or parent. And this list does not include provincial tax credits. On the basis of the federal tax credits listed here alone for which the CRA needs additional inputs, using the SPSD/M, we estimate that the CRA would have sufficient information on file to fill automatically the tax returns of about 58 percent of potential filers (“Basic Credits” in Table 1).

Filers, however, need simultaneously to have the characteristics of basic income sources, basic deductions and basic tax credits to have a truly basic tax return. When the three criteria are considered together, only about 32 percent of all potential filers would have a basic federal tax return – that is, a tax return for which the CRA would have on file all the required details on income, investments, expenses and personal circumstances (provided that the CRA has age, marital status and family composition on file) to enable the automatic and accurate calculation of taxes and benefits.

Clearly, the complexity of Canada’s personal income tax system is a challenge for implementing broad-based automatic tax filing. Only a minority of tax filers has a basic tax return. This is especially true for filers in mid- to high-income families: the CRA would have enough information provided by third parties to fill accurately the returns of only one in five.

The situation is more encouraging for potential tax filers in social assistance recipient families. Most have basic income sources, deductions and credits claimed. Yet, taken together, only half of filers in such families have a truly basic tax return. The same can be said of filers in lower-income families, of whom only 42 percent have a basic tax return.

It is also worth noting that, purely to determine eligibility for cash benefits, most of which are computed on the basis of net family income, the CRA would have enough third-party financial information to compute the income-tested cash benefit entitlements of nearly 70 percent of persons in families with income below $50,000 (not shown in Table 1).

Simplifying the personal income tax system would reduce the challenge of implementing automatic tax filing. Eliminating tax and benefit provisions recognizing spousal income, eliminating tax recognition of childcare and medical expenses, changing the tax treatment of spousal support and improving third-party reporting for income sources such as rental and self-employment income are a few examples of tax policy and process changes that could have a significant impact.

But tax simplification is a complicated affair in itself in Canada’s federal system. Tax preferences are used extensively by federal and provincial governments to achieve economic, social or purely redistributive objectives. Any real attempt at tax simplification is bound to lead to redistributive and economic impacts difficult to sustain politically.

Note that provinces derive substantial revenues from personal income taxes and enjoy broad autonomy over their income tax policies, which makes overall tax policy simplification still more difficult to achieve and maintain. Another complicating factor is Canadians’ love of tax preferences. Take the 2021 federal election as an example. All major parties included a number of new tax preferences in their platforms. Among the winner’s commitments are a few housing-policy-related tax preferences: a new Tax-free First Home Savings Account that will create a new tax deduction, doubling the First-Time Home Buyers’ Tax Credit, a new home renovation tax credit to help families transform their home by adding a multigenerational unit and a new tax credit to help cover the cost of appliance repairs. Other examples to highlight are one-time credits or benefits implemented for specific time-limited purposes. For instance, the special general-application tax credit for home office expenses, which many households claimed for the 2020 tax year due to COVID-19, or one-time home heating/energy credits established by federal and provincial governments to cover spiking energy costs in times of stress.

Tax policy changes are outside the purview of tax administration agencies. The current self-assessment with auto-fill tax-filing system greatly accommodates the current complexity of the tax code. Without fundamental tax policy reforms aimed at tax simplification, a broad-based automatic tax-filing system is unlikely to reduce compliance costs compared to the current auto-fill system: the majority of preliminary tax assessments prepared by the tax agency still would require further modification and optimization by tax filers. In a complex tax system, the need for tax advice does not stop with tax automation.

Getting Benefits into the Hands of Non-filers

Canadian governments provide citizens a number of cash benefits for which eligibility is tied to tax filing. These benefits are transfer payments granted to help families with the cost of raising children and housing, lower the burden of sales tax paid on purchases, lower the cost of carbon taxes in some provinces, support the retirement income of seniors, encourage individuals on welfare to take on paid work or low-income workers to continue working and provide targeted/time-limited assistance for other goals such as helping lower-income families with the cost of rising prices.

Cash benefit payments to working-age families have grown in importance in recent years.

The growing financial importance of such benefits in the lives of recipients leaves eligible recipients who do not file a tax return increasingly penalized. Indeed, non-filing reduces the effectiveness of Canada’s poverty-reduction goals (Petit et al. 2021; Robson and Schwartz 2020). Automatic tax filing, however, could lessen the extent of the problem. The number of non-filers can be implied by comparing the number of filers to the potential size of the filing population.

Estimating the Size of the Non-filing Population

The CRA reports the number of tax returns filed during the year of their due date – for example, it reports the number of returns filed in 2020 for the 2019 tax year. It also reports the number of returns filed during the year for any previous, overdue tax years. In 2020, about 29 million tax returns were filed for the 2019 tax year. An additional 1.9 million returns were filed (late) for previous tax years. The number of late returns processed has been relatively constant over the past five years, oscillating between 1.7 million and 1.9 million per year (Canada 2021d).

In Table 2, to estimate how many returns are filed (late or on time) in a given tax year, we propose a reasonable estimate of how many returns will be filed late – that is, past their due year. Our estimate is a conservative one, based on the difference between the number returns filed in their due year in 2019 and the CRA’s estimate of the number of individuals who participated in the tax system in the same year,

We then deducted the share of non-filers from the total population of potential filers. We considered everyone ages 19 and over to be a potential filer, since even a single individual with no income would at least be eligible for the GST Credit. Because not everyone younger than 19 is a potential filer, we consider 15-to-18-year-olds with earned income to be potential filers.

We estimated the number of non-filers for the 2019 tax year at about 4.2 percent of potential filers (Table 2). The non-filing rate appears to be decreasing slowly in recent years, from a high of 4.7 percent in 2016. Still, this leaves a substantial number of Canadians – about 1.29 million – who did not (or will not) file a tax return for the 2019 tax year.

Not all of the 1.29 million non-filers are potential cash benefit recipients. For example, employed individuals for whom sufficient income tax has been deducted at source by their employer might not file a return, yet their income level and personal circumstances might be such that they would not be eligible for any benefits. In addition, there were over 1 million non-permanent residents

Using Statistics Canada’s matching of Survey of Financial Security’s respondents to their personal income tax record (if present) as an indication of whether respondents are tax filers, Robson and Schwartz (2020) present a more detailed description of who did not file a tax return in 2016. They find that non-filing is much more prevalent among working-age, lower-income individuals, although, interestingly, when combined with other individual characteristics, the impact of low income itself is not sufficient to contribute significantly to the likelihood that working-age adults do not file. Women with young children, on the other hand, are significantly more likely to file a tax return, a result that is not surprising considering they are the main recipients of federal and provincial child-related tax benefits, by far the largest fiscal benefits available to working-age adults.

Robson and Schwartz’s finding that the low-income situation of non-filers is not sufficient on its own to explain their non-filing is particularly interesting. CRA research shows that housing-insecure people, those living in northern Canada, Indigenous people and recent immigrants are all disproportionately affected (Canada 2020c). Among the multiple barriers vulnerable populations face in filing a tax return are a lack of trust in government, health problems (mental or otherwise), unpaid existing or potential tax-related debts which they want to avoid, inadequate support or self-confidence or personal abilities, and cultural barriers. Lack of proper record-keeping and documentation is another key problem in an increasingly digital world, since all of the online and phone services offered by the CRA require verifying one’s identity. Identity verification can be very challenging for vulnerable people who might not be aware of specific details – for example, the value at specific lines on the prior year’s return – might move frequently and not be aware of their last address on file with the CRA or might experience language barriers (Canada 2020c).

Stapleton (2018, p. 6), based on his own extensive personal experience, consultations and focus groups with low-income populations, compiled “…[a] list of the concerns, both founded and groundless, that make many low-income people skeptical of government and averse to tax filing.” Some concerns are based on ignorance. For example, some people still erroneously believe that cash benefit entitlements administered through the tax system will be clawed back from their social assistance benefits. Or they do not understand how tax refunds work. Other concerns are based on fears that, by filing, they might invite the CRA to dig into past income sources and expose them to serious actions by government. “Uncertainty is an outsized problem for low income people” (Stapleton 2018, p. 7).

One such source of uncertainty is around casual work. “In our focus groups…everyone on a low income we spoke with…had worked in the informal economy for small amounts of money in service jobs such as home repairs, cleaning, or child care for cash” (Stapleton 2018, p. 7). But the amount of money involved in casual work of this kind among the working poor is so miniscule that the potential additional tax revenues realized by greater tax enforcement would pale in comparison with the internal costs of audits (Stapleton 2018).

Some non-filing individuals do not know that they stand to lose hundreds or even thousands of dollars in fiscal benefits by not filing. In 2017, the CRA launched a “non-filer benefit letter initiative,” in which letters were sent to potential fiscal benefit recipients who typically did not file a return, encouraging them to do so to receive their forgone benefits (Canada 2018b). From 2017 to 2019, more than 700,000 targeted letters were sent, and about 73,000 taxpayers (benefit recipients) filed a return as a result.

Robson and Schwartz (2020) have computed the value of selected benefits left on the table by non-filers: the GST Credit, the Working Income Tax benefit (now the Canada Workers Benefit), and child benefits offered by both federal and provincial governments. By not filing, working-age adults will have lost about $1.7 billion in benefits for the 2015 tax year – about 7 percent of the total value of benefits paid out – most of which can be attributed to lost child benefits. Robson and Schwartz do not provide the proportion of non-filers that would have been benefit recipients, but from their estimated median values of benefits, we can infer that the share is at least half.

Although the share of non-filers appears to have been on the decline in the past two years (Table 2), it is unclear if the value of forgone benefits has also declined. Also noteworthy is that the Robson and Schwartz (2020) survey-matching method for the 2015 tax year yields an estimated non-filing rate of 13.7 percent for potential filers ages 15 and over, which is much higher than our estimate of 4.5 percent, primarily based on administrative data from the CRA. If the actual non-filing rate was indeed lower than the estimate by Robson and Schwartz, the amount of benefits left on the table likely also was lower.

Other Considerations: Tax Avoidance, Fraud and Taxpayers’ Rights

Automatic filing could reduce tax-avoidance behaviour. Individuals who avoid or delay paying taxes by not filing a return would feel increased pressure to do so, if not simply because they had to file a return if they received a preliminary assessment. Automatic filing could also lead to distinct but related improvements to third-party income reporting, which is a primary deterrent of tax avoidance, and reduces “…the scope for shadow economy activity to remain undetected…” (OECD 2017, p. 30). On the other hand, automatic filing might create new risks of tax avoidance if mistakes are made in the taxpayer’s favour on a pre-filled tax form (Petit et al. 2021). Automatic filing might lead to a false sentiment of security on the part of the tax filer in not disclosing income sources about which the tax agency appears to know nothing.

When approving a tax assessment automatically generated by the tax authority, tax filers might be further inclined intentionally (or unintentionally) not to notice errors in their favour – exposing them to legal action and potential penalties – since, after all, the errors are not theirs, and correcting the errors might add complexity to a tax return that filers are not well equipped to cope with without professional advice. Research from a tax audit experiment in Denmark by Kleven et al. (2010) suggests that avoidance is higher for self-reported income (not pre-filled by the tax authority) than for income pre-filled in tax returns, and thus subject to third-party reporting (Fochmann et al. 2021). In Sweden, most people who omit income do so believing that everything has been accounted for in the return pre-filled by the tax authority (FTATSS 2006). In Denmark, “the penalty for non-compliance is the same whether the taxpayer actively gives false information or omits to correct the tax return. Deemed acceptance of an incorrect tax return is considered positive tax fraud” (FTATSS 2006, p.14).

Further, to the extent that automatic filing is introduced in a tax system with multiple provisions, taxpayers might fear targeted action by the tax authority for audit if they override calculations in a way that reduces their tax liability. As well, mistrust toward the tax authority might lead taxpayers to be hesitant about correcting a return in a way that benefits them because they might not wish to draw extra attention to themselves. Taxpayers intimidated by the tax authority’s assessment might opt for the easiest route – say nothing – for fear of facing penalties (Cordes and Arlene 2010).

Getting Benefits into the Hands of Non-filers: A Targeted Solution

An overarching consideration with respect to automated filing regimes where the tax agency prepares a preliminary tax assessment – whether taxpayer consent is mandatory or not – is that they work best when taxpayers face a simple tax situation. The number of tax deductions and credits reserved for specific circumstances adds to the complexity of the tax system and lowers considerably the number of taxpayers with basic returns. Making automatic filing more possible would require a concerted effort by federal and provincial governments to simplify the underlying tax system.

An important rationale for considering automatic tax filing is to ensure that non-filing low-income individuals receive the cash benefits – and eligibility to other support programs tied to tax filing – they are entitled to receive. But automatic filing for all is a sweeping solution for a narrow problem. As we have seen, about 4.1 percent of Canadians – or 1.29 million – do not file a tax return. Not all are low-income potential benefit recipients in vulnerable housing situations or health conditions, but it seems reasonable to assume that many are. Strategies targeting this subset of the population are more promising.

One such possible targeted strategy would be to remove the requirement to file a tax return to be eligible to receive benefits. This is not the same as, but in line with, what is done in the United Kingdom for most employed taxpayers: their tax situation is such that they are not required to file a tax return, yet they need to file separate claims to claim the Universal Credit (which replaces the Child Tax Credit and the Working Tax Credit) and the Child Benefit (United Kingdom 2021a, 2021c).

Establishing a new body specifically tasked with delivering income-tested benefits to Canadians could facilitate the decoupling of benefits from tax filing. Creating a fully functioning new separate agency could take a number of years. Alternatively, perhaps this separate benefit coordination function could be lodged within Service Canada at Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), as suggested by Robson and Schwartz (2021), which would seem to align with its current mandate, or it could remain within the CRA but be given an arm’s-length status and a separate identity. Such a body or coordination function inside another department would coordinate with provincial governments, which already deliver social assistance, and use information from other federal agencies such as the CRA to compute benefit entitlements – which would be possible most of the time – and ensure vulnerable, hard-to-reach people receive their entitlements.

A separate government body tasked with coordinating benefits would have some advantages over other possibilities. Non-filer eligible benefit recipients might be more willing to provide the required information – or consent to sharing information that could be obtained through third parties – if the coordination of cash benefits were not tied to tax filing. The low response rate to both the CRA’s “File My Return” invitations and the “benefit letters” initiative shows how difficult it is to elicit a response from the most vulnerable people. The CRA is primarily a tax collector, which comes with benefit-delivery hurdles such as general uneasiness or mistrust toward the tax authorities and misunderstanding about the crucial role played by tax filing in determining eligibility for cash benefits and other government support programs.

Robson and Schwartz (2021) point out a number of the CRA’s shortcomings in administering benefits relative to ESDC. On organizational focus, they report that 54 percent of ESDC’s workforce is assigned primarily to benefit programs administered by the department, while only 3.4 percent of the CRA’s workforce is assigned to benefits. Robson and Schwartz argue that the CRA’s primary focus on tax compliance creates a related incentive to maintain information asymmetries between taxpayers and the agency, which is not conducive to a fully transparent and “citizen-oriented” approach to dispute resolution and appeals on benefit decisions. In addition, the authors argue that interactions with the CRA are mainly through call centres and online services; by contrast, ESDC’s in-person local offices are better suited to the complex needs of those lacking “…the literacy, digital access, or confidence to navigate government services at a distance” (2021, p. 96).

A separate government body with a single mandate for benefit delivery arguably would perform these administrative functions better. In addition, it could be tasked with driving process improvements, such as real-time third-party reporting, that are crucial to benefit delivery but much less to tax filing. Petit et al. (2021) makes a powerful case for improving benefit delivery through real-time third-party income reporting. Currently, employers and financial institutions submit income information on individuals to the CRA on an annual basis, a few months after the end of the year. A long period, potentially greater than a year, can elapse between the time individuals suffer an income loss and the time they can start receiving benefits. More frequent third-party reporting of income earned by individuals could materially improve the responsiveness of the benefit system to changes in personal needs and circumstances.

A benefit-delivery model decoupled from tax filing also would come with challenges. Delinking the requirement to file taxes from the receipt of cash benefits might suggest that people have a choice not to have their income scrutinized by the CRA, and thus actually increase the number of non-filers. It is also important to consider that existing benefit recipients, who thus file a tax return, would not gain much, if anything, by a new benefit-delivery model. Depending on the new administrative processes in place, existing tax filers might resist using this new service, especially if it came with new claim requirements. In addition, governments or taxpayers generally might be uncomfortable with the idea of non-filers receiving cash benefits on the basis of an income attestation different than that provided by the CRA, especially if the risk of fraud is heightened or legal sanctions differ.

Other complications also could emerge. Provinces might object to a federal body distinct from the CRA administering their cash benefit programs, especially if costs were to go up. Exchange of information between the new body and third parties might lead to privacy issues. And some transfer programs administered through the tax system, such as the GST Credit, are still not accounted as spending in federal public accounts, but netted against tax revenues, even though they have all the characteristics of spending programs (Robson and Laurin 2017). Such a new benefit-delivery model thus could lead to new accounting challenges.

Despite the practical challenges, we think that, on balance, this proposal is worth serious consideration by governments, or at least further research. Untangling entitlements to cash benefits and other income-tested programs from the requirement to file a tax return could greatly improve access for a section of the population that needs it the most.

Conclusion

Making automatic tax filing broadly available in Canada is seriously challenged by the complexity of the tax code, which governments use to achieve social and economic goals. Without concerted federal and provincial efforts to simplify fundamentally the personal income tax system, fully automatic tax filing for all appears to be a very blunt instrument to get to the narrower problem of non-filing eligible benefit recipients.

More targeted strategies to reach non-filers are preferable. We propose that decoupling the requirement to file a tax return from eligibility to receive benefits is worth serious consideration. Despite practical challenges, establishing a new body specifically tasked with delivering income-tested benefits to Canadians could make this possible, better serving the poverty-reduction objectives of government support programs that are now tied to tax filing.

Appendix

References

Canada. 2017. EFILE for Individuals. Online at

https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue agency/services/e-services/e-services-individuals/efile-individuals.html.

———. 2018a. Non-Filer Benefit Letter Initiative – Qualitative Research. Canada Revenue Agency. Ottawa. October 19.

———. 2018b. 2017-18 Departmental Results Report. Ottawa: Canada Revenue Agency.

———. 2019. 2018-19 Departmental Results Report. Ottawa: Canada Revenue Agency.

———. 2020a. 2019-20 Departmental Results Report. Ottawa: Canada Revenue Agency.

———. 2020b. Population Projections for Canada (2018 to 2068), Provinces and Territories (2018 to 2043): Technical Report on Methodology and Assumptions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. June.

———. 2020c. Taxpayer Rights in the Digital Age: The Benefits and Risks of Digitalization for Vulnerable Populations in the Canadian Income Tax Context. Ottawa: Office of the Taxpayers’ Ombudsman. May.

———. 2021a. “Auto-Fill My Return.” Online at https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/e-services/about-auto-fill-return.html.

———. 2021b. Budget 2021. Ottawa: Department of Finance.

———. 2021c. “Do You Have to File a Return?” Online at https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/individuals/topics/about-your-tax-return/you-have-file-a-return.html.

———. 2021d. Individual Income Tax Return Statistics for the 2021 Tax-Filing Season. Canada Revenue Agency. August.

———. 2021e. Report on Federal Tax Expenditures – Concepts, Estimates and Evaluations 2021. Ottawa: Department of Finance.

———. 2021f. “Ways to Do Your Taxes.” Online at https://www.canada.ca/en/services/taxes/income-tax/personal-income-tax/get-ready taxes/ways.html.

Cordes, J., and H. Arlene. 2010. “Should the Government Prepare Individual Income Tax Returns?” Technology Policy Institute. September.

Fochmann, M., F. Hechtner, T. Kolle, and M. Overesch. 2021. “Combating Overreporting of Deductions in Tax Returns: Pre-filling and Restricting the Deductibility of Expenditures.” Journal of Business Economics 91 (1): 935–64.

FTATSS (Forum on Tax Administration Taxpayer Services Subgroup). 2006. Using Third Party Information Reports to Assist Taxpayers Meet Their Return Filing Obligations – Country Experiences with the Use of Pre-populated Personal Tax Returns. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. March.

Irish Tax and Customs. 2021. “Do PAYE Taxpayers Need to Submit a Tax Return?” Dublin. Online at https://www.revenue.ie/en/jobs-and-pensions/do-paye-tax-payers-need-to-submit-a-tax-return/index.aspx, accessed November 2021.

Kleven, H., M. Knudsen, C. Kreiner, S. Pedersen, and E. Saez. 2010. “Unwilling or Unable to Cheat? Evidence from a Randomized Tax Audit Experiment in Denmark.” NBER Working Paper 15769. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. February.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2017. Shining Light on the Shadow Economy: Opportunities and Threats. Paris: OECD. September.

———. 2019. Tax Administration 2019: Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies. Paris: OECD Library. September.

———. 2021. Tax Administration 2021: Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies. Paris: OECD Library. September.

Petit, G., M.L. Tedds, D. Green, and R.J. Kesselman. 2021. “Policy Forum: Re-Envisaging the Canada Revenue Agency – From Tax collector to Benefit Delivery Agent.” Canadian Tax Journal 69 (1): 99–114.

Robson, J., and S. Schwartz. 2020. “Who Doesn’t File a Tax Return? A Portrait of Non-Filers.” Canadian Public Policy 46 (3): 323–39.

———. 2021. “Policy Forum: Should the Canada Revenue Agency also Be a Social Benefits Agency?” Canadian Tax Journal 69 (1): 87–98.

Robson, W.B.P., and A. Laurin. 2017. Hidden Spending: The Fiscal Impact of Federal Tax Concessions. Commentary 469. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Stapleton, J. 2018. A Fortune Left on the Table: Why Should Low-Income Adults Have to Pass Up Government Benefits? West Neighbourhood House. June.

Tax Policy Center. 2020. “What Is Return-Free Filing and How Would It Work?” Washington, DC: Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

Trichur, R. 2020. “Why the CRA should do our taxes for us.” The Globe and Mail, March 5.

United Kingdom. 2021a. “Claim Child Benefit.” London: HM Revenue and Customs. Online at https://www.gov.uk/child-benefit/how-to-claim.

———. 2021b. “Income Tax Rates and Personal Allowances.” London: HM Revenue and Customs. Online at https://www.gov.uk/income-tax-rates.

———. 2021c. “Universal Credit.” London: HM Revenue and Customs. Online at https://www.gov.uk/universal-credit/how-to-claim.

Vaillancourt, F., M. Roy, and C. Lammam. 2015. Measuring Tax Complexity in Canada. Fraser Research Bulletin. Vancouver: Fraser Institute.

Vaillancourt, F., É. Roy-César, and M.S. Barros. 2013. The Compliance and Administrative Costs of Taxation in Canada. Studies in Tax Policy. Vancouver: Fraser Institute.

Wundertax. 2021. “Mandatory Tax Assessment: Who Has to File a Tax Return?” Online at https://germantaxes.de/tax-tips/who-has-to-file-a-tax-return, accessed November 2021.