The Study In Brief

The 2022 federal budget launched consultations on the implementation of new proposed rules for a Global Minimum Tax of 15 percent, which was endorsed in principle by members of the OECD and G20 in 2021.

In simple terms, the tax rules would apply to multinational enterprises (MNEs) with annual consolidated revenues generally of EUR 750 million. However, none of this is simple. The regime contemplates the introduction of a veritable tax smorgasbord, with countries grabbing for the taxes on a “first come, first served” basis.

In simple terms, the tax rules would apply to multinational enterprises (MNEs) with annual consolidated revenues generally of EUR 750 million. However, none of this is simple. The regime contemplates the introduction of a veritable tax smorgasbord, with countries grabbing for the taxes on a “first come, first served” basis.

For Canadian multinationals, the strategic considerations will include identifying and implementing arrangements that serve to reduce effective tax rates in all locations to 15 percent. Canada could win or lose. If a multinational group has foreign earnings in a jurisdiction that imposes increased taxes, then taxes on those earnings will be paid in that jurisdiction, leaving nothing to be taxed by Canada. In contrast, if the group can shift those foreign earnings (either by shifting the location of related activities or otherwise) to a low-tax jurisdiction, or to Canada, then taxes on those earnings will be paid in Canada.

For Canadian multinationals, the strategic considerations will include identifying and implementing arrangements that serve to reduce effective tax rates in all locations to 15 percent. Canada could win or lose. If a multinational group has foreign earnings in a jurisdiction that imposes increased taxes, then taxes on those earnings will be paid in that jurisdiction, leaving nothing to be taxed by Canada. In contrast, if the group can shift those foreign earnings (either by shifting the location of related activities or otherwise) to a low-tax jurisdiction, or to Canada, then taxes on those earnings will be paid in Canada.

Rather than raise additional revenues under the regime, Canada could suffer a net reduction in wealth and tax revenues. The reason: an increase in foreign taxes paid by Canadian-based multinationals would likely result in an offset against Canadian taxes otherwise payable by them; and, more importantly, result in a reduction in their after-tax foreign earnings.

Rather than raise additional revenues under the regime, Canada could suffer a net reduction in wealth and tax revenues. The reason: an increase in foreign taxes paid by Canadian-based multinationals would likely result in an offset against Canadian taxes otherwise payable by them; and, more importantly, result in a reduction in their after-tax foreign earnings.

Canada will need to consider very carefully how to restructure and optimize various elements of its tax and fiscal policy in order to maximize the attractiveness of Canada for all MNE groups as a location for activities and investment. It should create a climate in which Canadian MNE groups have the incentive to maximize the repatriation of their foreign earnings.

Canada will need to consider very carefully how to restructure and optimize various elements of its tax and fiscal policy in order to maximize the attractiveness of Canada for all MNE groups as a location for activities and investment. It should create a climate in which Canadian MNE groups have the incentive to maximize the repatriation of their foreign earnings.

Introduction

The so-called Global Minimum Tax of 15 percent, or the “Pillar Two” regime, as contemplated in the “October Statement” of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

If relevant foreign jurisdictions increase their tax rates accordingly (either in general or under Pillar Two), Canada’s adoption of Pillar Two might not raise the $3.5 billion in annual tax revenues initially estimated by Canada’s Finance Minister (Hall 2021).

Momentum has been building toward implementation of the minimum tax. The G20 leaders endorsed the October Statement, referring to it as a “historic achievement through which we will establish a more stable and fairer international tax system” (G20 Research Group 2021). Then, on December 20, 2021, the OECD released a package of Pillar Two model rules (the “Model Rules”), intended to “define the scope and set out the mechanism for the so-called Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) rules under Pillar Two” (OECD 2021a,b).

This E-Brief reviews the Model Rules, and their potential implications for Canada, in light of certain strategic and other considerations that may be relevant to how MNEs and various governments approach this initiative.

Overall Orientation

Despite the reference in the acronym GLoBE to “Anti-Base Erosion,” it is important to understand that this regime is no longer focussed only on situations involving tax base erosion. The Model Rules would apply not only to cross-border income streams derived through low-tax entities, but also to value-creating business activities carried on within any jurisdiction, including Canada, subject to a modest Substance-Based Income Exclusion applying to a portion of payroll and tangible asset costs.

Through a combination of mechanisms, the Model Rules would: (i) create implications and incentives or disincentives that would diminish – though not eliminate – the benefits for MNEs to derive cross-border income streams through low-tax entities; (ii) create incentives for certain governments to opportunistically raise their tax rates; and (iii) create disincentives for governments to rely on their tax systems as instruments of industrial and social policy, through the use of investment and development incentives.

The Mechanics of the Proposed Rules: Main Technical Elements

The Model Rules set out most of the main elements of Pillar Two, those being:

- an Income Inclusion Rule (or “IIR”), which consists of a main rule that would impose a so-called “Top-up Tax” on Ultimate Parent Entities, and certain other entities within an MNE Group,

The Model Rules contemplate the application of an IIR by Ultimate Parent Entities, as well as by Intermediate Parent Entities and Partially Owned Parent Entities. Priority goes to any Partially Owned Parent Entities, then to Ultimate Parent Entities, then to Intermediate Parent Entities. to make up for any difference between the Minimum Rate of 15 percent and the effective tax rate already imposed on foreign earnings;The commentary to Model Rule 2.1.6 contemplates that an IIR (a “domestic IIR”) could be applied by parent jurisdictions to domestic profits. - an Under-Taxed Payments/Profits Rule (“UTPR”), which consists of a back-stop rule that would allow subsidiary jurisdictions to impose a global Top-up Tax to the extent that parent jurisdictions failed to do so, and would even allow subsidiary jurisdictions to impose a tax at the Minimum Rate on the earnings of a parent company from activities in the parent jurisdiction;

Under the Model Rules, the UTPR is not limited to payments made to Low-tax Entities by entities within a UTPR jurisdiction (and the acronym is no longer associated with the word “payments”). The allocation key for residual Top-up Tax liability among qualifying UTPR jurisdictions is based on their relative numbers of employees (not payroll costs) and tangible asset costs. It is this feature that could allow a subsidiary jurisdiction to impose a Top-up Tax on the profits earned in a separate subsidiary jurisdiction or in a parent jurisdiction. This is somewhat controversial. See Li (2022), Plunket (2022), and Nikolakakis (2022). and - a Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax Rule (“QDMTT”), which consists of a rule that would allow all jurisdictions (that is, both parent jurisdictions and subsidiary jurisdictions) to impose a tax at the Minimum Rate on earnings from activities within their jurisdictions.

In addition to this, Pillar Two contemplates the possibility that jurisdictions could adopt a Subject to Tax Rule (“STTR”), in order to impose increased withholding taxes, capped at 9 percent (on a gross basis) rather than the 15 percent rate (on a net basis) applicable under the Model Rules, on certain payments to low tax entities, such as interest and royalty payments.

| Box 1: At a Glance. Some Key Acronyms in this Study |

|---|

|

GloBE: Global Anti-Base Erosion rules Also referred to as the Pillar Two Model Rules, they are designed to ensure large multinational enterprises (MNEs) pay a minimum level of tax of 15 percent on a net basis on the income arising in each jurisdiction where they operate. IIR: Income Inclusion Rule Under the IIR, the minimum tax is paid at the level of the parent entity, in proportion to its ownership interests in those entities that have low-taxed income. QDMTT: Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax Rule, or Domestic Top-up Rule Allows low-tax countries to apply a top-up tax on low-taxed entities within their borders without having to increase their low-tax rates – even no-tax jurisdictions can impose the top-up tax. UTPR: Under-Taxed Payments/Profits Rule, or Global Backstop The Undertaxed Payments/Profits rule (UTPR) has the same general purpose as the income inclusion rule (IIR). More specifically, the policy rationale of the UTPR is to serve as a backstop to the IIR, in the sense of allowing subsidiary jurisdictions to impose the Top-up Tax to the extent that parent jurisdictions fail to impose it under an IIR. STTRs: Subject to Tax Rules The STTR will be triggered where a covered payment is subject to a nominal tax rate in the payee jurisdiction that is below an agreed minimum rate of 9 percent on a gross basis. Sources: OECD at: https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/pillar-two-model-rules-in-a-nutshell.pdf CrossBorder Solutions at: https://crossborder.ai/article/could-pillar-two-mean-double-taxation-for-mnes/ |

Jurisdictions would also be free to apply income attribution rules, such as Canada’s “foreign accrual property income” (“FAPI”) rules (“Controlled Foreign Company” / “CFC Rules”), and to treat foreign entities as being fiscally transparent (“Hybrid Rules”), and thereby tax their income in the hands of their equity holders.

In terms of relative priorities, the Model Rules contemplate that STTRs and QDMTTs (as well as normal local income taxes) would take precedence over the IIR and the UTPR, and the IIR would take precedence over the UTPR. Thus, a parent jurisdiction seeking to impose an IIR would be required to offset any foreign tax imposed under a STTR or a QDMTT. Likewise, a jurisdiction imposing tax under a UTPR would be required to offset any tax imposed by another jurisdiction under a STTR or a QDMTT or an IIR. What remains a bit uncertain at this stage is whether taxes imposed by a parent jurisdiction under CFC Rules or Hybrid Rules would take precedence over the QDMTT, although it seems clear that they would take precedence over the IIR and the QDMTT.

The Model Rules contemplate the following process for determining the required Top-up Tax:

- MNE Groups would first determine the jurisdictional location of all their Constituent Entities (“CEs” or “entities”), which would include all entities and permanent establishments, as defined.

Permanent establishments would constitute CEs that are separate from the Entities to which they belong. - MNE Groups would then compute their Excess Profits for each relevant jurisdiction (i.e., each separate jurisdiction where a parent has entities), based on the net GLoBE Income of all entities located in that jurisdiction. An important distinction to consider is that GLoBE Income is to be determined using entities’ financial accounting principles (adjusted in accordance to Model Rules) as opposed to domestic tax rules. Excess Profits for each jurisdiction would exclude a Substance-Based Income Exclusion, which after a 10-year transition period would be determined as 5 percent of eligible payroll and 5 percent of eligible tangible asset costs within that jurisdiction.

The transitional rules contemplate an initial rate of 10 percent of payroll costs and 8 percent of tangible asset costs, declining annually until the 5 percent rate is reached. - MNE Groups would then compute, for each relevant jurisdiction, the aggregate Adjusted Covered Taxes allocated to that jurisdiction (essentially, any income taxes, including under STTRs, already imposed or accrued separately from the Model Rules), based on financial accounting tax expense (including both the current tax provision and certain items of the deferred tax provision), adjusted in accordance with the Model Rules.

- MNE Groups would then determine the effective tax rates for each jurisdiction (essentially, the aggregated Adjusted Covered Taxes over the aggregated Net GLoBE Income for each jurisdiction) which, compared to the Minimum Rate, would yield the jurisdiction’s Top-up Tax Percentage.

- Finally, the Top-up Tax Percentage for each jurisdiction would be applied to the Excess Profits of that jurisdiction, then any QDMTT for that jurisdiction would be deducted, yielding the ultimate amount of the Top-up Tax liability for that jurisdiction. The aggregate amount of Top-up Tax liability for each jurisdiction where a parent has entities would then have to be imposed by the UPE jurisdiction (or another parent jurisdiction) under an IIR, failing which it could be imposed by a subsidiary jurisdiction (or a parent jurisdiction) under a UTPR.

Under the Model Rules, a parent jurisdiction could also technically be a UTPR jurisdiction. It can also impose a QDMTT, or a domestic IIR.

However complex this process may seem, the reader should bear in mind that the above description is a bare-bones simplification of it.

It is also important to emphasize that, under the Model Rules, a significant change has been made to the UTPR. Under previous descriptions, this mechanism would serve in part as a back-stop to the IIR mechanism, but it would only apply to the extent that deductible payments are made to low-tax entities. This is no longer the case under the Model Rules. The UTPR continues to serve as a back-stop to the IIR, but now it would apply regardless of whether or not deductible payments are made to low-tax entities. Thus, the UTPR would allow a subsidiary jurisdiction to impose Top-up Tax on earnings that have no connection to activities within that jurisdiction (e.g., to profits from value-creating activities in another subsidiary jurisdiction or in a parent jurisdiction). Thus, for example, if the Excess Profits of a Canadian MNE from activities in Canada have an effective tax rate below 15 percent, and Canada has not opted to impose a QDMTT (or has not yet done so), then any jurisdiction in which the MNE group may have operations can impose a Top-up Tax on the Canadian Excess Profits, under a UTPR.

Strategic Considerations for MNEs

For MNE groups, the strategic considerations would include identifying and implementing arrangements that serve to reduce the effective tax rate in all locations to 15 percent. These may also include considerations relating to selecting the jurisdictions to which there may be a preference to pay their taxes, for a variety of reasons. For example, if a Canadian-based MNE has foreign earnings in a jurisdiction that imposes a QDMTT, then taxes on those earnings will be paid in that jurisdiction, leaving nothing to be taxed by Canada, even if Canada adopts an IIR. In contrast, if the MNE group can shift those foreign earnings (either by shifting the location of related activities or otherwise) to a low-tax jurisdiction that does not have a QDMTT, then taxes on those earnings will be paid in Canada, assuming Canada adopts an IIR. Depending on a variety of considerations, be they strategic or patriotic, Canadian-based MNE groups may prefer to pay the taxes on their foreign earnings either to foreign jurisdictions or to Canada.

Strategic Considerations for Low-Tax Jurisdictions

For low-tax jurisdictions, an important consideration would be whether or not to adopt a QDMTT. If the relevant income will in any event be taxed under an IIR, these jurisdictions may feel that they have nothing to lose and only tax revenues to gain, opportunistically, from the adoption of a QDMTT. However, on the other hand, since a QDMTT takes priority over an IIR, it may also be rational for (some of) these jurisdictions to decline to impose a QDMTT, either in general or at least in certain cases, in order to attract activities and income from MNE Groups that would prefer, for strategic or other reasons, to pay their Top-up Taxes to their parent jurisdictions. Increasing normal tax rates is also an option, but perhaps not preferable to adopting a QDMTT, because that tax would apply only to large MNEs, and would include a Substance-Based Income Exclusion, allowing the continued use of incentives within that threshold.

Strategic Considerations for Canada

For relatively high-tax jurisdictions such as Canada, the adoption or not of a QDMTT also gives rise to strategic and other considerations. Since the Model Rules are not limited to cross-border income flowing through low-tax jurisdictions, it would in general be rational for jurisdictions like Canada to adopt a QDMTT, in order to tax income that would in any event be subjected to an IIR (or a UTPR) in another jurisdiction, thereby diminishing treasury transfer effects.

We will also have to consider how to restructure our incentive programs in ways that are optimal in light of the Model Rules. For example, under the Model Rules, so-called Qualified Refundable Tax Credits are accounted for as additional earnings and thus do not reduce tax expense, whereas other credits are accounted for as reductions to tax expense. The difference is important, because items that resemble government grants and are therefore accounted for as additional earnings may result in Top-up Tax liability equal to 15 percent of such additional earnings, whereas items accounted for as reductions in tax expense may result in Top-up Tax liability equal to 100 percent of such reductions.

The treatment under the Model Rules of costs such as resource royalties (and similar impositions) is also something to consider – in that some of these could be accounted for as reductions in earnings rather than as tax expense.

Simply put, Canada will want its incentive tax benefits to be accounted for as earnings (or not even as earnings at all, if possible) rather than as reductions in tax expense, and will want its royalties and other such impositions to be accounted for as tax expense rather than as reductions in earnings.

In a sense, Canada has already had to consider these types of questions, because of our exposure to the US Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (“GILTI”) regime, which can affect incentives to Canadian operations of US MNE groups. GILTI is somewhat of a hybrid between a minimum tax and a CFC Rule. It provides for US taxation of the foreign earnings of US MNE groups (computed under US tax principles rather than financial accounting principles), at about half the normal US tax rate (and subject to a limited credit for any qualifying foreign taxes). The substance-based income exclusion under GILTI only takes into account a percentage of tangible asset costs (and not any payroll costs), and is computed on a world-wide basis rather than on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis. However, because of Canada’s disproportionate exposure to the US economy relative to other countries, the exercise becomes more complicated, to the extent that our approach will have to strive toward optimality in light of both the Model Rules and the US GILTI regime, which may or may not be modified to become consistent in certain contexts over the years.

In addition, while the US GILTI regime mainly affects only Canadian operations of US MNE groups, which parallels, although not exactly, the impact of the IIR on the Canadian operations of other MNE groups, the UTPR is much broader in that it can affect the Canadian operations of Canadian MNE groups, since it allows subsidiary jurisdictions to tax the Canadian earnings of Canadian MNE groups, as noted above in relation to the structure of our incentive programs and other features of how we tax Canadian operations.

Another important consideration for relatively high-tax jurisdictions such as Canada is whether or not, and how, to restructure their international tax systems in order increase the probability that their MNE groups would pay the Top-up Tax to those jurisdictions rather than to foreign jurisdictions. For example, since the spread between the Minimum Rate and the Canadian rate on foreign earnings remains considerable at more than 10 percent, MNE groups would continue to have the incentive to localize such earnings in foreign jurisdictions, with a view to paying no more than the Minimum Rate. It is difficult to imagine that MNE groups would consider it consistent with their competitiveness imperatives to collapse their foreign tax arrangements and start paying taxes on such earnings in Canada, unless Canada were to reduce the Canadian rate on foreign earnings to (or to a rate that is much closer to) the Minimum Rate.

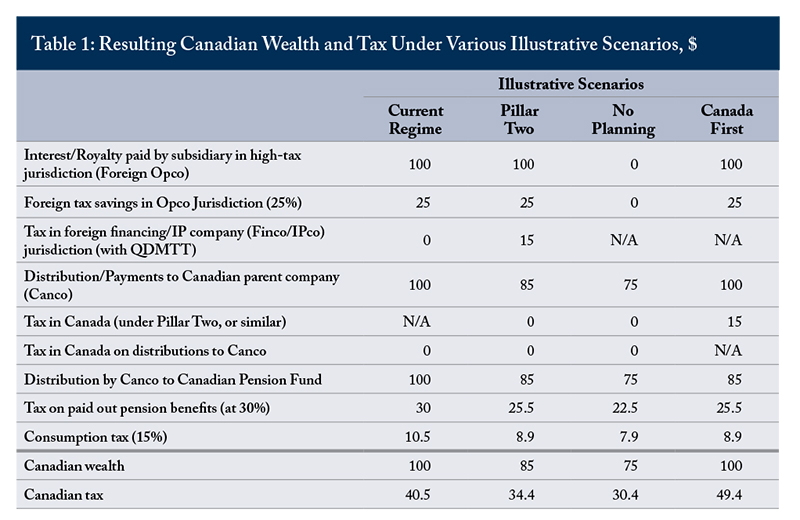

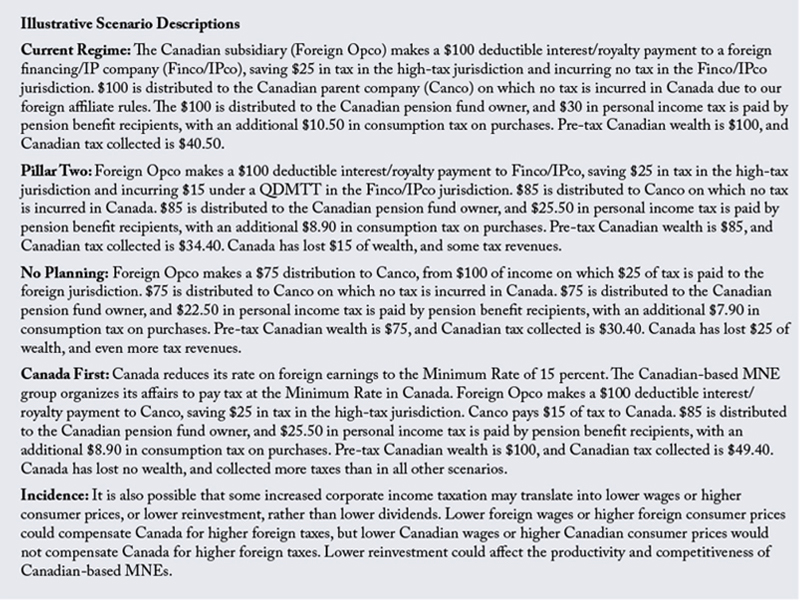

Table 1 compares four illustrative scenarios involving a Canadian-based MNE with operations in a high-tax foreign country, using as an intermediary a traditional no-tax group financing company or intellectual property (“IP”) company. For simplicity, the Canadian-based MNE is owned by a Canadian pension fund exempt from taxes on the dividend distributions it receives. The current regime is compared to the Pillar Two regime and a “Canada First” regime in which Canada reduces its rate on foreign earnings to the Minimum Rate of 15 percent so that the Canadian-based MNE group organizes its affairs to pay tax at the Minimum Rate in Canada.

The differences between the various scenarios are material. If Canada simply adopts Pillar Two without making other strategic adjustments, we will likely be impoverished. The best outcomes would arise if Canada were to adopt a Canada First approach, whereby Canadian MNE groups had the incentive to reduce foreign taxes, in a way that results in Canada being the country that collects the 15 percent Global Minimum Tax. This may take some political finesse, but the policy considerations are pretty clear.

Conclusion

In brief, the Pillar Two regime contemplates the introduction of a veritable fiscal smorgasbord, with countries grabbing for the taxes on a “first come, first served” basis. MNE groups will strive toward achieving an effective tax rate in every jurisdiction of no more than 15 percent. Canada will need to consider very carefully how to restructure and optimize various elements of our tax and fiscal policy in order to maximize the attractiveness of Canada for all MNE groups as a location for activities and investment, as well as to create a climate in which Canadian MNE groups have the incentive to maximize the repatriation of their foreign earnings.

This initiative will continue to develop in the coming months and years as countries work through the Implementation Framework. Things to watch for will include: (i) the basic progress and evolution of this initiative (or lack thereof – as there are already some signs it may be delayed); (ii) the possibility of the US GILTI regime (among others, including the US FDII and BEAT regimes) being modified and/or being declared to be compatible or incompatible with the Pillar Two regime; and (iii) how various other countries may revisit and adapt their tax and fiscal policy choices in order to maximize their respective strategic interests.

References

G20 Research Group. 2021. “G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration.” University of Toronto. October 31. Available at www.g20.utoronto.ca.

Hall, Chris. 2021. “Global tax accord could earn Canada up to $4.5 billion per year, says Freeland.” CBC News. October 16. Available at www.cbc.ca/news/politics.

Li, Jinyan. 2022. “The Pillar 2 Undertaxed Payments Rule Departs From International Consensus and Tax Treaties.” Tax Notes International. March 21.

Nikolakakis, Angelo. 2021. “Global Tax Deal: Who Wins and Who Loses?” Intelligence Memo. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. October 19.

________________. 2022. “Bait and Switch – A Reply to Casey Plunket.” Tax Notes International. April 11.

OECD/G20. 2021. “Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy.” OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. October 8.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2021a. “OECD releases Pillar Two model rules for domestic implementation of 15% global minimum tax.” News Release. December 20. Available at www.oecd.org/tax/beps.

________________. 2021b. Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy – Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two). Paris: OECD. December 1420. Available at www.oecd.org/tax/beps.

________________. 2022a. Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy – Commentary to the Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two). Paris: OECD. March 14. Available at www.oecd.org/tax/beps.

________________. 2022b. Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy – Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two). Examples. Paris: OECD. March 14. Available at

www.oecd.org/tax/beps.

________________. 2022c. “Tax challenges of digitalisation: OECD invites public input on the Implementation Framework of the global minimum tax.” News Release. March 14. Available at

www.oecd.org/tax/beps.

Plunket, Casey. 2022. “What’s in a Name? The Undertaxed Profits Rule.” Tax Notes International. March 28.