Less for Ottawa, More for Canadians: The C.D. Howe Institute’s 2024 Shadow Budget

- The federal government’s 2023 Fall Economic Statement confirmed a troubling lack of concern about fiscal excess. It presented no credible plan to lower spending and borrowing to levels that would ensure fiscal sustainability and make room for tax changes to boost Canada’s stagnating productivity and living standards. This Shadow Budget sets out a program, with spending restraint at its centre, that will produce surpluses by the 2027/28 fiscal year, set the ratio of net federal debt to GDP on a path toward its level before the COVID pandemic, and make room for growth-enhancing income-tax relief.

- To make these gains durable, this Shadow Budget launches a comprehensive review of federal spending that will make programs more effective, efficient and fair. Its review extends to tax provisions that are spending programs in disguise, relabelling them as appropriate, and subjecting them to the same formal scrutiny appropriate to all spending. It also initiates a process to legislate controls on deficit spending.

- Canada’s tax system hampers growth. It taxes personal and corporate incomes too heavily and imposes disproportionate compliance costs. This Shadow Budget makes a start on shifting the tax burden away from income. It reforms small business taxation to incentivize growth. It rescinds recent narrowly targeted tax hikes that undermine growth and fairness. It also contains measures to better meet the needs of an ageing population, address recent stresses in immigration and labour markets, and reduce food prices by promoting competition in supply-managed products.

- The measures in the C.D. Howe Institute’s 2024 Shadow Federal Budget will reduce the pressure of federal spending and borrowing on Canada’s economy, improve the equity and effectiveness of federal programs, and make room for personal and corporate income-tax relief to stimulate growth. Canadians are suffering declines in living standards. This Shadow Budget is the change of direction the country needs.

We thank Daniel Schwanen, John Lester, Rosalie Wyonch, Jeremy Kronick, Gerald MacGarvie, Nick Pantaleo and anonymous reviewers and members of the C.D. Howe Institute’s Fiscal and Tax Competitiveness Council for helpful comments on an earlier draft. We are also grateful for reviewers of previous Institute Shadow Budgets, which prefigured many of the ideas presented in this one. Responsibility for any errors and the views expressed is ours.

Overview

The federal government’s 2023 Fall Economic Statement (FES) showed scant concern for Canada’s economic and fiscal prospects. Nowhere did it acknowledge the implications of high public debt for future taxes, economic growth, fiscal sustainability or intergenerational fairness. Restraint measures were tiny compared to recent and projected spending and borrowing and also lacked credibility after repeated massive overruns in spending. It said little, and did nothing, to address stagnation in Canadian per-person output and living standards. It did not acknowledge the intergenerational unfairness of its fiscal stance, all the more serious in the light of such risks as climate change, stubborn inflation, an ageing population, and geopolitical and technological risks. It did not even address immediate challenges that are top-of-mind concerns for Canadians, such as access to primary healthcare and affordable housing.

This 2024 Shadow Budget changes course. It takes immediate measures to rein in spending and borrowing, aiming for a balanced budget by the 2027/28 fiscal year. It reduces the federal government’s reliance on personal and corporate income taxes. And it contains initiatives to improve the coherence of Canada’s tax system, promote economic growth and charitable giving, and help Canadians prepare for demographic ageing.

The Bottom Line: Fiscal Results of the Shadow Budget

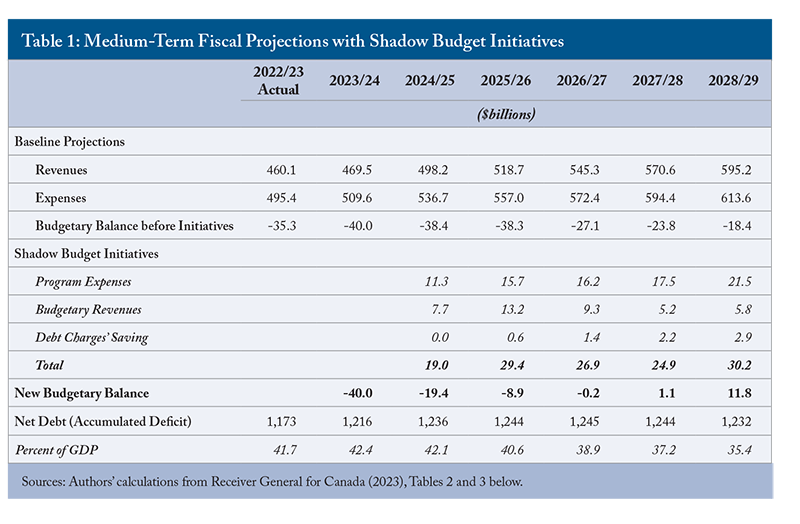

A primary purpose of a budget is to present the federal government’s financial situation and prospects. Unlike the most recent federal budget, which buried the key fiscal numbers more than 200 pages deep in an annex, we begin the Shadow Budget with a summary statement of transactions that reflects the proposed policy actions (Table 1).

The Shadow Budget restores surpluses by 2027/28. An end to new borrowing signals decisively that the government recognizes that borrowing simply defers taxes that ought to cover programs enjoyed in the present, and that ever-mounting debt and debt-servicing costs will erode the federal government’s ability to deliver services.

The ratio of the federal government’s net debt – its accumulated deficit – to GDP was 31.2 percent before the pandemic. This ratio was low enough to make debt servicing costs manageable, and gave the government flexibility to respond to the crisis. An appropriate medium-term goal is a federal debt-to-GDP ratio back at or below that level. This fiscal plan lowers the debt ratio from its current level of 42.4 percent to 35.4 percent by 2028/29. A few more years of surpluses would lower it to a level more consistent with fiscal stability and intergenerational fairness.

The Status Quo Outlook Facing the Shadow Budget

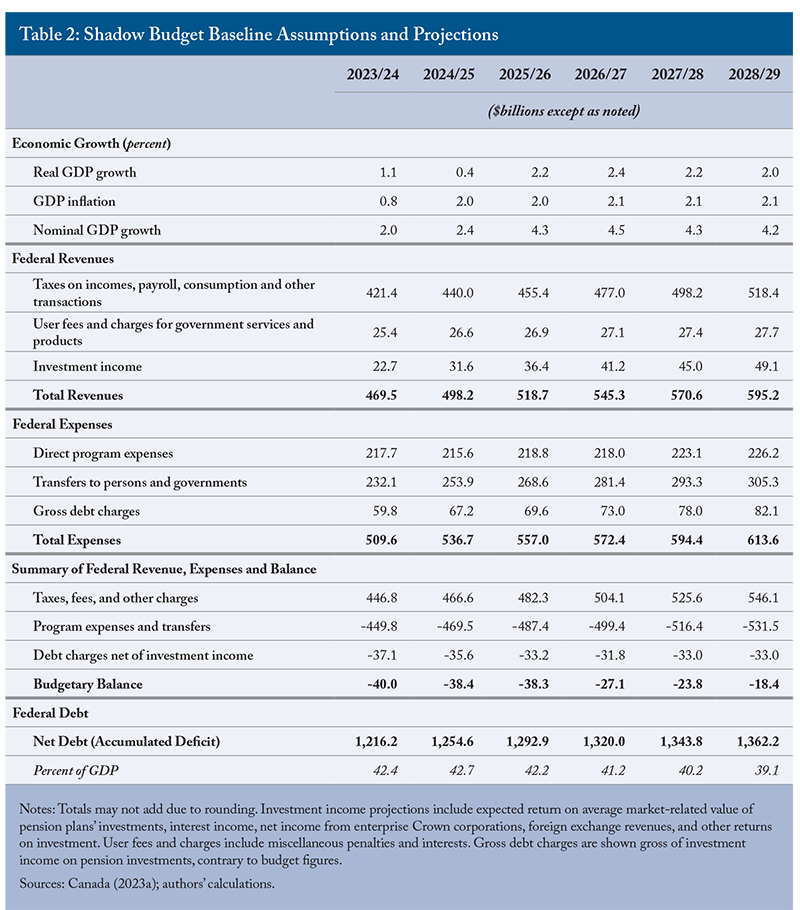

Our starting point is the 2023 Fall Economic Statement (FES, Canada 2023a). The FES featured large deficits through 2028/29 and a debt-to-GDP ratio that barely declines from this year’s 42.4 percent (Table 2).

Growth in program expenses, even before including net actuarial losses – belated recognition of the cost of the federal government’s pension obligations, which it shows below subtotals for expenses and deficits that exclude the losses – underlies the unsatisfactory FES fiscal results. From $263.6 billion in 2015/16, program expenses less net actuarial losses grew at an average annual pace of 6.5 percent to $338.5 billion in 2019/20. The pandemic caused spending to soar to $608.5 billion in 2020/21. Only some of this increase reversed in the following two years. After 2022/23, when program expenses excluding actuarial losses tallied $438.6 billion, the FES projected them to grow to $534.1 billion by 2028/29. That would make annual average increases of 5.2 percent since 2019/20 and 5.6 percent since 2015/16 – after the pandemic-related measures are well in the past.

Even after taking account of price increases – which were themselves exacerbated by excessive government spending – the growth rate is faster than the Canadian economy can match with 2 percent inflation. While some of this explosion of spending is higher transfer payments that are valuable to their recipients, not all the transfers are wise policy, and much of the explosion is higher operating spending. The higher cost of the federal government has not produced any proportional improvement in the quality of federal public services – indeed, key functions, notably defence, increasingly seem inadequate to meet the needs of Canadians and Canada’s role in global affairs.

Policy Actions in the Shadow Budget

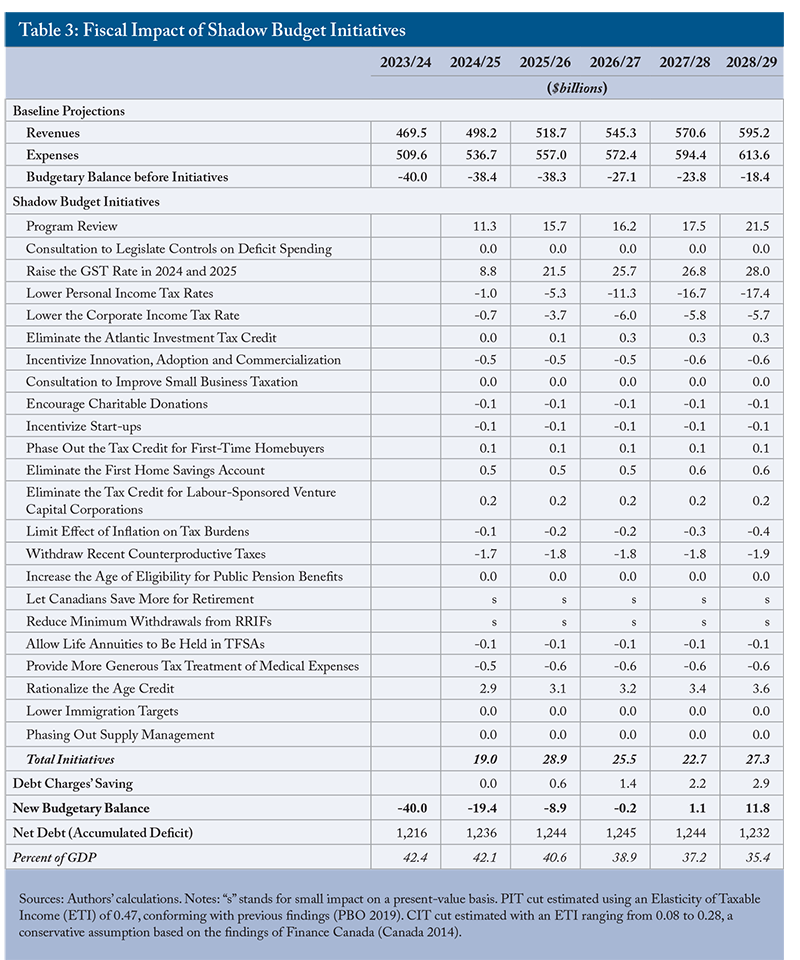

Table 3 below shows the magnitude of actions necessary to go from the starting point of the FES to the fiscal results in the Shadow Budget.

Returning the budget to balance requires spending restraint. The savings proposed in the 2023 Budget, and currently being pursued by the President of the Treasury Board, amounted to only $15.3 billion over five years. The exercise proposed in this Shadow Budget goes deeper, with more solid supporting processes. That greater effort reflects the fact that spending has grown rapidly and is currently very high.

Relative to the program expenses in the FES, it requires savings of $11.3 billion in 2024/25, growing to $21.5 billion by 2028/29. In that final year of the Shadow Budget, the spending cut is 4 percent of the spending level (before actuarial losses) projected in the FES – a cumulative $82.2 billion.

The growth rate of program expenses (before actuarial losses) from 2023/24 through 2028/29 averages 3.0 percent annually in the Shadow Budget compared to 3.8 percent in the FES. Even after this restraint, the average annual growth rate would be a robust 4.7 percent since 2019/20 and 5.2 percent since 2015/16. The level of spending after the proposed restraint should be adequate to fund key priorities.

The savings will come from a Program Review exercise involving all federal departments and agencies. That review includes the following common and overarching elements.

• Competitive compensation for federal employees.

• Transition of federal employees to jointly governed shared-risk pension plans – a change with little short-term fiscal impact, but that will reduce the actuarial losses that have added some $112 billion to the federal government’s debt

over the past decade.

• Less use of consultants with better processes for selection and accountability.

• Better procurement, including in defence, where equipping the armed forces must take precedence over other considerations, such as regional pork barreling.

• Rigorous evaluation of all programs, including regulations, at least every four years, supervised

by a central body, reviewed by Parliament, and made public.

A core feature of the restraint is containing the costs of the federal public service. Federal full-time-equivalent employment increased 4 percent a year on average from 2017/18 to 2022/23, an expansion coinciding with an explosion of government contracting for work public servants could or should be doing. This Shadow Budget would reduce departmental operating budgets for current compensation to their 2023 levels and hold them there for five years. This approach, conceptually similar to the approach suggested by Lahey (2011), will bring federal compensation better in line with private-sector compensation and curtail the growth of the federal payroll. Managers would have latitude within their budgets to reward high performers and reduce less-valuable positions. This measure lowers federal spending by $1.5 billion in fiscal year 2023/24, growing to $8 billion annually over the projection period.

Financing for any new spending must come from reallocations to achieve the total targets. This Shadow Budget does not expand federal support for dental care. It does not proceed with a national Pharmacare program. To address some drug affordability challenges, it proposes a reform of the medical expenses credit. Should Pharmacare proceed, the incremental federal cost would need to be fully funded.

The Program Review exercise will not be only about cuts, but about reallocations to higher priority areas. For example, Canada needs to shift care of the elderly away from the heavy reliance on long-term care institutions toward home and community-based care with their lower costs and higher satisfaction to seniors. The federal government should contribute money to a national effort and that funding would need to come out of the envelope described above with its 3 percent annual growth cap.

Programs should be evaluated against their efficiency and effectiveness in achieving desired outcomes. The evaluations should recognize the economic damage done by the taxes that fund them. Many existing programs can be expected to fail a proper evaluation.

Many federal tax provisions are spending in disguise. Unlike measures such as deductions to avoid double taxation or avoid taxing income needed for non-discretionary expenses – often termed “structural” measures (Canada 2023b) – many credits and other provisions are like subsidies or transfer payments. Yet they are subject to much less scrutiny than other spending, with only a few being evaluated each year by Finance Canada with little involvement of Parliament (Robson and Laurin 2017). The Shadow Budget launches a process for a more thorough review of these provisions.

Like spending programs, each tax expenditure needs to be reviewed no less frequently than every four years to ensure its objectives are valid, and that it is operating efficiently and fairly. The results should be published and reviewed by Parliament. Redesign or elimination of tax expenditures will permit less borrowing and further income-tax relief.

Preparing for Legislative Controls on Deficit Spending

This Shadow Budget starts a consultation process to legislate controls on deficit spending. Its main focus will be on non-cyclical spending – that is, programs whose yearly cost is not dictated by the state of the economy, whether it is booming or slumping. The government should set up a rolling multiyear ceiling on non-cyclical spending such as personnel expenses, temporary income supports, buildings, procurement, dental care, and government transfers for health, education, infrastructure, groceries and childcare.

One way to legislate a more sustainable fiscal framework would be to enshrine specific fiscal rules in legislation, as is done in many other countries. Another approach, used by New Zealand, and recommended by Lester and Laurin (2023), would be to enshrine guiding principles for sustainable deficit and debt management in legislation, while allowing some discretion in their application, but subject to an independent assessment of compliance by, for example, the Parliamentary Budget Office.

Improving the Efficiency and Fairness of the Tax System

Spurring growth requires relying less than Canada currently does on taxes that discourage work, saving and investment.

The present GST Credit is mis-named. It is the single most important example of a “tax expenditure” that is disguised spending (Robson and Laurin 2017). Showing it as a reduction in taxes understates how much the government spends and how much GST Canadians pay. Beneficiaries’ payments are based on their incomes, completely unrelated to how much GST they pay. It did not fall when the GST rate fell from 7 percent to 5 percent in the 2010s, and the federal government used it as a tool to provide additional income support – the “grocery rebate” – during the pandemic. This Shadow Budget renames it as the Canada Income Support and shifts it from a deduction from GST revenues to the expenditure side of the ledger. The 2024 Fall Economic Statement will show the results of this change in historical data, and the 2023/24 Public Accounts will reflect it in the government’s statement of operations.

The need to balance the budget limits scope for personal income tax relief in the near term, but a downpayment on further progress is possible. Personal marginal effective tax rates tend to be much higher at mid-income levels due to the effect of income-tested reductions of cash benefits (Laurin and Dahir 2022), so targeting middle-income levels makes sense. This Shadow Budget will lower the tax rate for the second tax bracket, ranging from $55,867 to $111,733 in 2024. The Parliamentary Budget Office found that individuals in the second-bracket range responded significantly to the 2016 “middle class tax cut” by increasing their taxable income (PBO 2019), which is consistent with the objective of the tax reform. Under our Shadow Budget, the second-bracket tax rate will decrease from 20.5 percent to 19 percent in 2025, then to 17 percent in 2026. In 2027, it will go to 15 percent – the same rate as for the lowest bracket – reducing the number of federal tax brackets from five to four.

This Shadow Budget will also lower the general corporate income tax rate by one percentage point in 2025 and a further one percentage point in 2026. Lower corporate income tax rates will lead to more capital investment and increase economic growth in the long term. The Atlantic Investment Tax Credit will disappear in 2026. These changes will reduce growth-inhibiting tax distortions and signal the government’s intent to continue with tax reforms that will boost productivity and wages over the medium and long term.

To incentivize the creation and commercialization of intellectual property, this Shadow Budget establishes an “IP Box” tax mechanism whereby income from patents and other intellectual property generated by activity in Canada would face a lower corporate tax rate (Lester 2022).

This Shadow Budget announces a consultation process to improve the small business taxation regime. The goal is to provide stronger incentives for businesses to continue to grow since larger firms tend to be more productive, pay higher wages, export more and research more. Higher tax rates at threshold levels of annual income or assets discourage growth. Providing a lower tax rate on cumulative income up to a threshold, by contrast, could encourage growth by supporting young businesses rather than all small businesses.

This Shadow Budget exempts from taxation capital gains realized on the sale of certain publicly traded small-business shares. As under similar provisions of the US Small Business Jobs Act, investors will qualify for this capital gains tax exemption if they hold qualified small business shares for at least five consecutive years, encouraging the kind of patience needed to grow small and medium-sized enterprises (Schwanen et al. 2019).

This Shadow Budget eliminates the tax credit for Labour-Sponsored Venture Capital Corporations (LSVCC). The LSVCC distorts savings and investments and is an ineffective, inefficient way of encouraging innovation (Fancy 2012).

This Shadow Budget phases out the tax credit for first-time homebuyers. The credit stokes housing demand that already exceeds supply. This Shadow Budget also eliminates the First Home Savings Account, which also stokes demand and undermines the tax system by providing tax deductions on contributions yet allowing tax-free withdrawals.

To encourage charitable donations, this Shadow Budget relieves more donations of private company shares and real estate from capital gains tax (Aptowitzer 2017). Proposed reforms to the alternative minimum tax as they apply to the treatment of charitable donations would be discarded.

The personal income tax system is only partially indexed to inflation, so rising prices and wage increases that merely match inflation raise real tax burdens. Examples of parameters without indexation include the federal government’s pension income credit and the maximum education and tuition credits that tax filers can transfer to spouses or parents (Robson and Laurin 2023). The Shadow Budget indexes these parameters.

Revoking Inefficient and Unfair Tax Measures

Taxes cause least economic damage when their bases are broad, and when individuals, companies and activities that are comparable are taxed equally and fairly. Treatment that is economically illogical and violates principles of equity promotes further damage, undermining confidence in the integrity of the system and encouraging lobbying for more special treatment. This Shadow Budget pauses or eliminates a number of problematic recent measures.

• It rescinds the temporary exemption of home heating oil from the carbon tax.

• It revokes the “luxury tax” on cars, boats and airplanes.

• It revokes income surtaxes and taxes on intercorporate dividends imposed on financial institutions.

• It revokes the tax on share buybacks.

The new digital tax would be postponed, setting aside for the moment Canada’s unilateral route in favour of working for a multilateral solution. This position could be revisited should the attempt fail.

This Shadow Budget also launches a review of the compliance burden of taxes that yield relatively little revenue and impede the Canada Revenue Agency’s ability to focus on more important tax bases. Among the initial subjects of the review will be trust reporting rules and new taxes related to underused housing and short-term rentals.

Lowering the public debt burden will help prepare Canada for population ageing and reduce intergenerational unfairness. This Shadow Budget goes further to prepare Canadians collectively and individually for the demographic changes to come.

Reflecting increased longevity and future fiscal pressures, it phases in increases to the normal age of eligibility for Old Age Security, which will rise in monthly increments from 65 at the beginning of 2023 to 66 in 2034, and then to 67 between 2048 and 2050. The actuarial adjustments that penalize or reward early and later commencement of benefits would apply from the new ages, ensuring that people who cannot work past the current earliest age of eligibility could still collect reduced benefits, while further encouraging later receipt by people willing and able to work and save for longer.

Seniors are now the age group in Canada least likely to live in poverty, making the historical emphasis on preferential taxation of the elderly inappropriate. The Shadow Budget reduces the base amount of the age credit from $8,793 to $4,000. As further Personal Income Tax relief, through lower rates and higher thresholds, becomes possible, the age credit will phase out.

Limits on tax-deferred saving in Canada put savers in defined-contribution pension plans and RRSPs at a disadvantage relative to participants in defined-benefit plans (Robson 2017). The Shadow Budget raises the limit for contributions to the former plans by three percentage points of income per year – from the current 18 percent to 30 percent of earned income – over four years. This Shadow Budget also proposes to relieve pressure on people to liquidate those savings too early. It proposes an immediate one-percentage-point reduction of minimum withdrawals from Registered Retirement Income Funds (RRIFs) mandated for each age, beginning with the 2024 taxation year.

Given that Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) are displacing RRSPs for a number of taxpayers, this Shadow Budget provides greater flexibility in savings vehicles, such as making it possible to buy annuities within a TFSA.

The ageing of the Canadian population, in particular the doubling over the next two decades of the cohort age 75 and over, will push healthcare spending up. Canada relies heavily on relatively expensive long-term care for the elderly, even though most seniors would prefer other, less costly, options. While elderly care falls mainly in provincial and municipal jurisdictions, the federal government’s involvement in healthcare financing gives it influence in developing better homecare and community-living systems. The spending review outlined in this Shadow Budget can accommodate temporary federal support of provincial efforts. Once new programs and facilities are in place, the costs of system reform will end, and this additional federal funding will not be needed.

The current medical expense tax credit applies only to expenses exceeding 3 percent of net income or $2,759, whichever is lower, and is calculated at the bottom tax rate. The Shadow Budget would lower the threshold on such expenses to 1.5 percent of net income, or $1,380, whichever is lower, relieving more income needed for nondiscretionary expenses from taxation. This measure will to a degree fill the affordability objectives of a national Pharmacare program, which this Shadow Budget does not pursue.

Alleviating the Pressure of Population Growth on Housing and Healthcare

The government’s targets for new permanent residents – 485,000 this year and 500,000 per year beyond 2024 – along with an explosion in temporary foreign workers and foreign students are exacerbating pressures on housing and access to primary care. To alleviate these pressures, this Shadow Budget prefigures:

• A reduction in the target for new, permanent residents to 350,000 per year, and a corresponding increase in the thresholds for acceptance in the Comprehensive Ranking System from its current record low level.

• Less and better-targeted admissions for temporary foreign workers with a shift in emphasis away from low-paying jobs.

• Continuation of the recently announced cap on foreign student visas, which would decrease by 35 percent in 2024 from the 2023 level.

Reducing the Cost of Basic Groceries

Government-mandated cartels in eggs, dairy and poultry products impose high costs on consumers and harm Canada’s ability to negotiate access for its products abroad (Robson and Busby 2010; Schwanen, Robson and Bafale 2023). This Shadow Budget initiates a process to phase out supply management through sales of new quotas for the production and sale of these products. A consultation process will determine the appropriate balance of benefits for consumers and the transition for producers.

Conclusion

The measures in the C.D. Howe Institute’s 2024 Shadow Federal Budget put the federal government on a path to budget balance and ultimately reduce the federal debt-to-GDP ratio below its pre-pandemic level. Restraint of spending and modest increases in the GST will create room for reductions in personal and corporate income taxes – small at first, but larger later as fiscal pressure recedes. These changes improve the prospects for Canadians to earn more and enjoy higher living standards – a stark contrast to recent stagnation. We encourage federal legislators to support the measures in the Institute’s 2024 Shadow Budget.

References

Aptowitzer, Adam. 2017. “No Need to Reinvent the Wheel: Promoting Donations of Private Company Shares and Real Estate.” E-Brief 265. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. September.

Canada. 2014. Tax Expenditures and Evaluations. Ottawa: Department of Finance Canada.

______. 2023a. Fall Economic Statement. Ottawa: Department of Finance Canada.

______. 2023b. Report on Federal Tax Expenditures – Concepts, Estimates and Evaluations 2023. Ottawa: Department of Finance Canada.

Fancy, Tariq. 2012. “Can Venture Capital Foster Innovation in Canada? Yes, but Certain Types of Venture Capital Are Better than Others.” E-Brief 138. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. September.

Lahey, James. 2011. “Controlling Federal Compensation Costs: Towards a Fairer and More Sustainable System.” In How Ottawa Spends, 2011-2012. Christopher Stoney and G. Bruce Doern, eds. Pages 84–105. Montreal; Kingston, ON: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Lester, John. 2022. “An Intellectual Property Box for Canada – Why and How?” E-Brief 326. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. April.

Lester, John, and Alexandre Laurin. 2023. “Ottawa Needs a New Approach to Fiscal Policy.” E-Brief. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. March.

Laurin, Alexandre, and Nicholas Dahir. 2022. Softening the Bite: The Impact of Benefit Clawbacks on Low-Income Families and How to Reduce It. Commentary 632. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. November.

Parliamentary Budget Office. 2019. “Revisiting the Middle Class Tax Cut.” Ottawa. April.

Receiver General for Canada. 2023. Public Accounts of Canada, 2023. Ottawa. October.

Robson, William B.P., and Colin Busby. 2010. Freeing Up Food: The Ongoing Cost, and Potential Reform, of Supply Management. Backgrounder 128. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. April.

Robson, William B.P. 2017. Rethinking Limits on Tax-Deferred Retirement Savings in Canada. Commentary 495. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. November.

Robson, William B.P., and Alexandre Laurin. 2017. Hidden Spending: The Fiscal Impact of Federal Tax Concessions. Commentary 469. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. February.

Robson, William B.P., and Alexandre Laurin. 2023. “Double the Pain: How Inflation Increases Tax Burdens.” E-Brief. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. August.

Schwanen, Daniel, Jeremy Kronick, and Farah Omran. 2019. “Growth Surge: How Private Equity Can Scale Up Firms and the Economy.” E-Brief. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. May.

Schwanen, Daniel, William B.P. Robson and Mawakina Bafale. 2023. “Don’t Let the Dairy Lobby Win this Fight.” C.D. Howe Institute Intelligence Memo. October 13.