The Municipal Money Mystery: Fiscal Accountability in Canada’s Cities, 2023

by William B.P. Robson and Nicholas Dahir

- The budgets municipal governments present around the beginning of their fiscal years, and the audited financial statements they publish after year-end, are crucial for decision-making and accountability. A review of the budgets and audited financial statements of 32 major Canadian municipalities reveals a troublingly mixed picture.

- The fiscal accountability grades in our 2023 report card ranged from A to F. Quebec City and Richmond earned As for the clarity, completeness and timeliness of their presentations. Markham, Saskatoon and Vancouver, each with A-, also stood out favourably. Hamilton, London and Windsor earned Fs, reflecting multiple problems with transparency and timeliness.

- Although some were late and/or missing information, most municipalities’ financial statements earned high scores for presentation and conformity with public sector accounting standards (PSAS). But many municipal budgets provided no PSAS-consistent numbers and presented fragmented information, separating operating and cash-based capital budgets, and tax- and rate-supported activities.

- Too many budgets were late, with councillors approving operating and capital budgets after the start of the fiscal year, when money was already committed or spent.

- Confusing and late budgets discourage engagement and informed input. Municipalities should use the same PSAS-consistent presentations in their budgets that they do in their financial statements, using accrual accounting for capital and showing their full activities and claims on citizens’ resources. Along with timelier presentations, these changes would raise the fiscal accountability of Canada’s municipalities to a level more commensurate with their importance in Canadians’ lives.

This report is part of an ongoing C.D. Howe Institute project on municipal fiscal accountability. We thank people who provided comments before or after publication of earlier reports in the project, and Alexandre Laurin, Clae Hack, Bonnie Lysyk, and members of the C.D. Howe Institute’s Fiscal and Tax Competitiveness Council for comments on earlier drafts of this one. We are responsible for the conclusions and any errors.

Note to Readers: This is a revised version of the Commentary first published in April 2024. It features revised scores for Burnaby.

Introduction and Overview

Canada’s cities provide vital infrastructure and services, for which they raise, receive, and spend large amounts of money. The quality and cost of municipal services affect where households and businesses live and invest, and a city’s capacity to deliver services affects the living standards of its residents.

All municipal governments should present financial information that achieves high standards of transparency, usefulness and timeliness. However, as this fiscal accountability report card on the budgets and financial statements of 32 major Canadian municipalities reveals, many do not.

Although this report highlights some concerns with municipalities’ year-end audited financial statements – notably with timeliness – the clarity and accessibility of these statements are generally good. They follow public sector accounting standards (PSAS) and get clean opinions from their external auditors.

The budgets presented by municipalities around the beginning of their fiscal years, however, are generally not good. Many understate the size of city operations, omit key activities and exaggerate the costs of capital projects. In most cities, simple questions – such as how much the government plans to spend, how plans compare with current activities, and the implications of plans for future capacity to deliver services – are impossible for non-experts to answer. Canada’s cities routinely run surpluses – often large ones – which their budget documents do not prefigure. Worse, councillors often vote on budgets after the fiscal year has started, and receive financial information too late for use in budget decisions for the upcoming year.

These shortcomings have consequences. Big price tags for capital projects can discourage councillors from investing in certain long-life infrastructure and induce them to raise too much money up front to finance the projects they do undertake. Focusing on cash transactions also encourages neglect of future obligations, including repair and replacement of infrastructure.

Confusing budgets undermine engagement. Why would citizens pay attention to municipal finances, make representations to their councillors, or attend public meetings if they do not understand the numbers or if they think budgets are misleading? Discussions about potential changes in taxes, services or government transfers would be more fruitful if more people knew that Canada’s cities are in better financial shape than most budget debates suggest.

All municipalities should present budgets that match their year-end financial statements. Provincial governments that impede municipal budget presentations based on PSAS – for example, by requiring separate operating and capital budgets – should stop. Municipal budgets should present gross consolidated revenues and expenses rather than netting the cost of services such as water, sewage and parking against fee revenues – which hides important activities and means that only those with the financial expertise and ample time will be able to compare budget intentions with actual results. Municipalities that face provincial or other impediments to preparing PSAS-consistent budgets should publish supplementary information on their own, to enable budget-results comparisons.

Better and timelier budgets and financial statements would elevate the financial oversight and management of Canada’s municipalities to a level more appropriate to their importance in Canadians’ lives.

Measuring Fiscal Accountability

Financial documents help people make decisions and monitor results. To be useful, they must be accurate, complete and timely, and formatted so users can readily find and interpret the principal numbers. These requirements matter at least as much in government reporting as anywhere else, since paying taxes is not optional and accountability for public funds underpins representative government.

Legislators and citizens need to monitor whether public employees are doing what they should be doing, and citizens need to monitor whether legislators are doing what they said they would do. Along with measures of performance – such as on-time departures in transit, thoroughness in waste removal and quality of drinking water – financial documents should let legislators and citizens monitor what is happening and take corrective action.

At a minimum, a government’s financial documents should let a reader who is motivated and numerate, but not an expert in accounting, find consolidated revenues and expenses and the resulting surplus or deficit, and relate those numbers to changes in the government’s accumulated surplus and its capacity to deliver future services.1 These documents should inform councillors as they authorize spending, taxing and borrowing, not perplex them.

The Fiscal Cycle and Principal Documents

A municipality produces two key documents in its annual fiscal cycle: its budget and its financial statements.

The budget contains fiscal plans for the coming year. It is the main opportunity for councillors and the public to learn about, and provide input on, municipal priorities. Budgets should prompt scrutiny and debate in councils and the media. Ideally (as is the case for most senior governments but for too few municipalities, as we will see) budgets highlight a projected statement of operations showing consolidated revenues and expenses, along with the resulting annual surplus or deficit, and the impact that surplus or deficit will have on the municipality’s accumulated surplus – its capacity to deliver future services. Councillors should consider the annual budget well in advance of the fiscal year to have time to deliberate before funds are committed or spent.

The audited financial statements produced after year-end show what a municipality actually raised and spent during the year, and the resulting change in its accumulated surplus. Prepared according to PSAS, these statements present actual revenues and expenses and the year-end financial position, with councillors and the public getting additional assurance from certification by external auditors. The timeliness of the issuance of audited financial statements also matters, partly because councillors can address any problems the statements reveal before they become “old news”, and partly because speed in collecting and validating information helps provide estimates for the year about to end, and hence a more solid baseline for the upcoming year’s budget.

Most of the municipalities we looked at in this report included their audited financial statements in annual reports, along with further financial analysis and discussion. We used a municipality’s annual report when it was available and graded the municipality based on the information it contained, including summaries of information from the financial statements highlighted early in the report.

The starting points for engaged users of a government’s budget or financial statements are the comprehensive figures for revenues, expenses, the annual surplus or deficit, and the accumulated surplus or deficit. The concerned citizen, councillor or journalist will want to know what revenues and expenses it plans to receive and incur in the coming year, or what revenues and expenses it actually received and incurred in the year just past. Those numbers are the basis for understanding how planned revenues and expenses compare to past results, how well actual revenues and expenses corresponded to past plans, and to see, understand and potentially investigate changes or variances.

To address these questions, users who are numerate and motivated, but not necessarily experts, need budgets and financial statements that:

- present the key numbers early and identify them prominently;

- use PSAS-consistent accounting with consolidated figures providing the full picture of the municipality’s activities;

- use consistent numbers that allow comparisons of intentions and results; and

- are timely, with the budget approved well before the start of the year, and financial statements published shortly after the end of the year.

The financial reports of well-run Canadian public businesses, not-for-profits and most Canadian senior governments (Robson and Dahir 2023) have these features. Senior governments’ consolidated revenues and expenses and annual and accumulated surpluses or deficits usually appear clearly on one page in their budgets and financial statements.

The financial statements of most municipalities in this survey score well on these criteria. The same is not true of their budgets. Most city budgets are not consistent with PSAS. Readers of those budgets cannot easily find comparisons between the city’s projections and past results, and they cannot find what the budget’s bottom line implies for the change in the city’s accumulated surplus by year-end. Many municipalities are late with their budgets; some finalize them months after the fiscal year has begun and after the money councillors have not yet approved is already spent.

The Challenge of Non-PSAS-Consistent Municipal Budgets

People who are new to municipal budgeting are often surprised that most Canadian cities’ budgets do not match their financial statements, and may be doubly surprised that our recommendation that they should match is controversial. Most municipal budgets depart from PSAS in two major ways.

The first departure is with respect to accrual accounting. Accrual accounting shows revenues and expenses during the period when the relevant activity occurs, rather than when cash changes hands. It records the expenses associated with long-lived items such as buildings, bridges, roads and sewers as they deliver their services – ideally, writing them down (amortizing them) until they wear out. This approach means that the difference between consolidated revenue and expense, the surplus or deficit, represents the change in the government’s accumulated surplus – its capacity to deliver services – over the course of the year.

PSAS mandate accrual accounting. But although municipalities use accrual accounting in their budgets in some areas, such as receivables and payables, they typically do not use it for capital projects. Instead, they apply cash accounting to capital outlays as they occur – a big cost upfront and nothing thereafter. They also typically present separate operating and capital budgets, rather than showing PSAS-consistent consolidated revenues and expenses, as they do in their financial statements. This difference makes most municipal budgets impossible for non-experts to reconcile with municipal financial statements.

Under accrual accounting, cash collected in taxes or received from senior governments in transfers to finance capital items need not be recorded as revenue until the item in question is delivering its services. Until it is recorded in revenue, the cash on the asset side of the municipality’s statement of financial position has a counterpart liability, usually labelled “deferred revenue.” That label signifies that the money is not the city’s to do with as it pleases; its obligation is to use the money to build the item.2

In most municipal budgets, the focus on cash and the separation of operating and capital budgets means funds received during the year but not used for capital outlays during the year flow into “reserves,” and funds received in prior years used for capital outlays during the year flow out of “reserves.” A city’s operating budget adds flows of funds out of reserves to operating revenue and adds flows of funds into reserves to operating spending. That treatment makes no sense: it mixes items that do not affect the annual surplus or deficit – and the city’s accumulated surplus and capacity to deliver services – with items that do. The focus on cash and the separation of operating and capital budgets also means that most municipal budgets omit the amortization of capital assets as they deliver their services – a large category of expense for municipalities which are capital-intensive operations.

The other major deviation from PSAS in many municipal budgets is the fragmented reporting of revenue and expense. PSAS require consolidated numbers, capturing the full range of activities under the control of the reporting entity. Many municipal budgets separate tax-supported from fee-supported services, and sometimes show only net figures – inflows minus outflows – for the latter. That practice deprives users of the big picture and drives another wedge between the presentations of budgets and financial statements, frustrating attempts to compare plans and results.

Rating Municipal Budgets and Financial Reports

This overview of users’ needs and existing practices sets up a closer look at municipal budgets and financial statements, and the criteria we used to grade them. This evaluation is not about whether municipalities tax and spend too much, or too little, or in the wrong ways. It is about how well their financial documents help councillors and the public to make such judgments. Our scores on each of the criteria reflect the range between good and bad performance. We weight each criterion’s score in the overall grade according to our judgment of its importance to overall fiscal transparency and accountability.

Except for Halifax, whose fiscal year – like the fiscal years of all Nova Scotia municipalities – runs from April 1 to March 31, our municipalities budget and report on calendar years: January 1 to December 31. Spending without authorization by elected representatives violates a core principle of democracy: formal passage of a budget is a major event not only for taxpayers, but also for departments and municipally funded organizations that cannot make commitments if they do not know what resources they will have. Councillors should consider their budget well before the fiscal year starts, and vote on it before the year starts. We awarded a top score of 2 if a municipality approved its budget 30 days or more before the fiscal year started, 1 if it approved the budget less than 30 days before the year started and 0 if approval occurred after the year started.

Timely publication of financial statements helps councillors and others to react to deviations of results from plans. It also encourages faster gathering of information, which gives budget planners more up-to-date estimates for the year about to end. Untimely financial statements can signal trouble. Late statements are a red flag for auditors, for donors to charities, and for investors in companies. The Ontario Securities Commission requires TMX-listed companies to file their annual results no later than three months after year-end (OSC 2023) – a deadline the Commission itself also achieves. We used the date of the auditor’s signature on the financial statements in our scores. This is not an ideal dating system, since time can pass between the auditor’s signature and the public posting of financial statements. But the signature is easier to verify than the financial statements, which are often undated. We awarded a top score of 2 to municipalities with an auditor’s signature no more than 90 days after year-end, 1 to municipalities with a signature more than 90 days but no more than 181 days after year-end and 0 to municipalities with a signature more than 181 days after year-end.

Key numbers should be easy to find and identify. No user should have to search through dozens of pages in a document or slide deck wondering where the headline numbers for consolidated revenue, expense and surplus or deficit are. Municipal financial statements usually present these numbers early and identify them clearly. Many municipal budgets do not. Our score on this criterion reflects where the numbers appeared: closer to the front of the document is best, as it reduces the chance that a user will give up or encounter wrong figures before finding the right ones.

We looked through the most prominently displayed budget documents posted on a municipality’s website, stopping at the first aggregate figures identified as relevant totals. When similar-looking documents appeared equally prominently – similar fonts and colours on clickable links, for example – we chose the first one in the list or menu.

We referenced the physical budget books and financial statements or annual reports, or their electronic PDF equivalents.3 We began our count at the first physical or electronic page, omitting pages containing tables of contents and lists of tables and figures, since they help readers navigate the document.

For budgets, we awarded a top score of 3 to municipalities that displayed consolidated revenues and expenses and the surplus or deficit – or, in the case of municipalities with separate operating and capital budgets, their operating and capital totals – within the first 15 pages of the document. We awarded a score of 2 to municipalities that presented those numbers from 16 to 30 pages into the document, 1 to municipalities that presented them from 31 to 50 pages in, and 0 to municipalities that presented them more than 50 pages in or did not present both operating and capital totals.4 We awarded a further point to municipalities that presented operating and capital totals on the same page. Municipalities that presented their budgets on a PSAS-basis showing consolidated totals automatically earned that point.

We also looked at the placement of any reconciliation between the budget totals and PSAS-consistent numbers. We awarded 3 points to municipalities that presented the reconciliation within the first 30 pages of their budget documents, 2 to municipalities that presented the reconciliations 31 to 60 pages in, 1 to municipalities that presented the reconciliation after the first 60 pages, and 0 to municipalities that did not present a reconciliation.

For annual reports and financial statements, we used the same placement scores as for budgets, counting the pages to the first table that provided the consolidated revenue, expenses, and surplus. We did not scale our scores according to the overall length of the documents – by using percentages, for instance – because long documents are less user-friendly than short ones.

In cases where a municipality provided similar information in more than one place – a comparison of budget projections to past results, for example, or a reconciliation of a non-PSAS-consistent budget presentation with PSAS-consistent numbers – we used the presentation that appeared first in the document.

Reliability and Transparency of Numbers

For both budgets and financial statements, we asked if a user could readily find consolidated revenues and expenses and the projected or actual annual surplus or deficit,5 and relate those projections to the projected change in the government’s accumulated surplus or deficit, all presented in accordance with PSAS. We discuss the audited financial statements first because the generally high quality of municipal financial statements allows a relatively straightforward scoring system.

Financial statements are more useful if they show and explain differences between results and budget plans. PSAS-consistent budgets would make scoring these comparisons easier. As the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB) has noted, “[t]he actual-to-budget comparison is meaningful when the budget: (a) is prepared on the same basis of accounting (i.e., accrual accounting), (b) follows the same accounting principles (i.e., the standards in the PSA Handbook), (c) is for the same scope of activities (i.e., includes all components, where applicable, and all controlled entities), and (d) uses the same classification (i.e., revenue by type and expenses by function or major program) as the financial statements” (PSAB 2021, 34). Few municipalities do this. Even those that presented PSAS-consistent aggregate numbers in their budgets usually did not break down revenues and expenses the same way they did in their financial statements. So we resorted to less complete measures of consistency. We awarded 2 points to municipalities that presented budget projections alongside their results if the revenue, expense and bottom-line numbers in those budget projections matched the numbers in the budget itself. We awarded 1 point to municipalities that presented budget projections if those numbers did not match the numbers in the budget itself, but the statements provided a reconciliation to the original budget numbers. We awarded 0 to municipalities that did not present budget projections beside their results or presented budget projections that did not match what appeared in the budget itself. We awarded an additional point when the statements explained the variations between projections and results.

As for conformity with PSAS in financial statements, we awarded 2 points to municipalities with unqualified audit opinions, and 1 point to the one municipality, Montreal, that had one qualification in its audit opinion. We would have awarded 0 to any municipality with more than one qualification, or that explicitly did not conform to PSAS. We weight this score relatively heavily in our overall grades.

With respect to budgets, which are messier, we looked first at whether a municipality presented PSAS-consistent consolidated revenues, expenses and the surplus or deficit. We awarded 1 point for each.

We then looked at how prominently the budget presented PSAS-consistent numbers. We awarded a score of 3 to the one municipality, Richmond, that presented a PSAS-consistent budget. We awarded 2 to municipalities that did not present PSAS-consistent numbers as their primary exhibits but provided prominent reconciliations to PSAS-consistent numbers – “prominent” meaning the reconciliation was listed in the table of contents, and/or appeared in the main budget tables and/or had its own section in the text, rather than appearing in an appendix or a supplemental section. We awarded 1 to municipalities that provided a reconciliation but did not present it prominently. We awarded 0 to municipalities that did not present PSAS-consistent numbers at all, or that presented incomplete numbers that did not help users anticipate what a full reconciliation would show.

Because many municipalities did not present PSAS-consistent numbers in their budgets, we also looked at whether a municipality presented gross expenditures – both tax- and rate-supported – to give users a better view of operating spending’s projected claim on community resources. We awarded 2 to municipalities that presented gross expenditures as their unique headline numbers; 1 to municipalities that presented net and gross expenditures equally prominently; and 0 to municipalities that presented only net expenditures in their headline numbers, did not consolidate rate- and tax-supported expenditures, and/or otherwise omitted government-controlled entities.6 Municipalities that presented PSAS-consistent consolidated expenses got the top mark of 2 on this criterion.

A budget should show projections for the coming year alongside expected results for the current year – the year about to end – and historical results for at least one year before that. This presentation allows users to see whether their municipality expects revenue and expenses to rise or fall, and by how much. Most of Canada’s senior governments show both those comparisons, with presentations that show not just total revenue and expense, but also the major components of revenues and expenses.

Unfortunately, none of our 32 cities produced a budget comparing projections to anticipated results for the current year using PSAS-consistent numbers. The prevailing practice is to compare the budget to the previous year’s budget. Although that approach would strike most managers of businesses and not-for-profits, and many household budgeters, as minimally useful, it is so prevalent that we accommodated it in our scoring system.7 We awarded 3 to municipalities that provided a comparison of the current year’s budget to the previous year’s budget using PSAS-consistent numbers. We awarded 2 to municipalities that presented comparisons to the previous year’s budget for operating and capital spending, 1 to municipalities that did so for operating spending only, and 0 to municipalities that provided no budget comparison or provided incomplete comparisons.

Adjustment Below the Annual Surplus/Deficit Line

A final criterion we used in evaluating municipal audited financial statements focused on whether the difference between revenues and expenses – the annual surplus or deficit – related straightforwardly to the change in the municipality’s accumulated surplus, representing its capacity to deliver services, over the fiscal year. A line such as “other comprehensive income or loss” between the year’s surplus and the associated change in the accumulated surplus loosens that link. We penalized those lines for that reason.

This treatment is less straightforward than a penalty for a fault such as omitting key numbers or getting a qualified audit opinion. PSAS allow or mandate below-the-line adjustments in some circumstances, such as gains and losses of city-owned enterprises. This example illustrates the justification for such lines: gains or losses on investments council does not control directly differs from revenues and expenses council does control. It also illustrates why they are problematic: a municipality that reports such gains and losses has undertakings that expose taxpayers to risks that councillors cannot budget for or control.

A further concern is that a reporting entity may take advantage of such an adjustment to move something embarrassing out of revenues or expenses, and the surplus or deficit. For example, a municipality might take advantage of flexibility in timing to omit an expense in one year to produce a bigger surplus for that year, and report that expense in a later year as a reconciliation item that most users likely will ignore.

We awarded 1 to municipalities that had no such adjustment and 0 to municipalities that had one. The fact that below-the-line adjustments not flagged by auditors are consistent with PSAS led us to weight this criterion relatively lightly in our overall grades.

The 2023 Report Card on Canada’s Major Municipalities

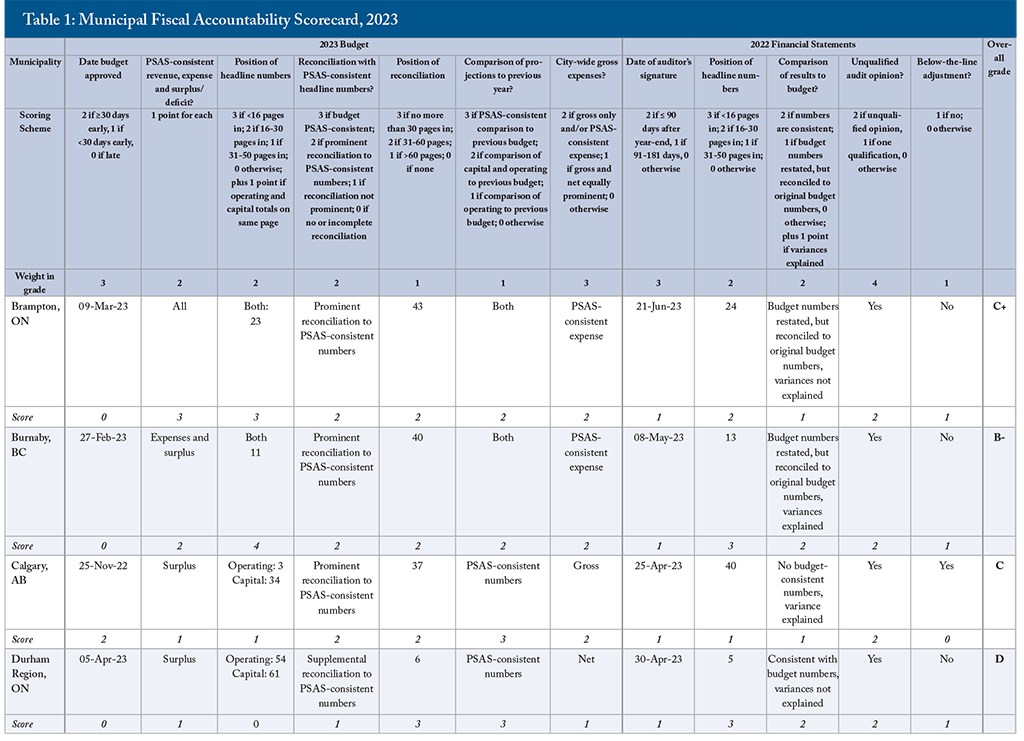

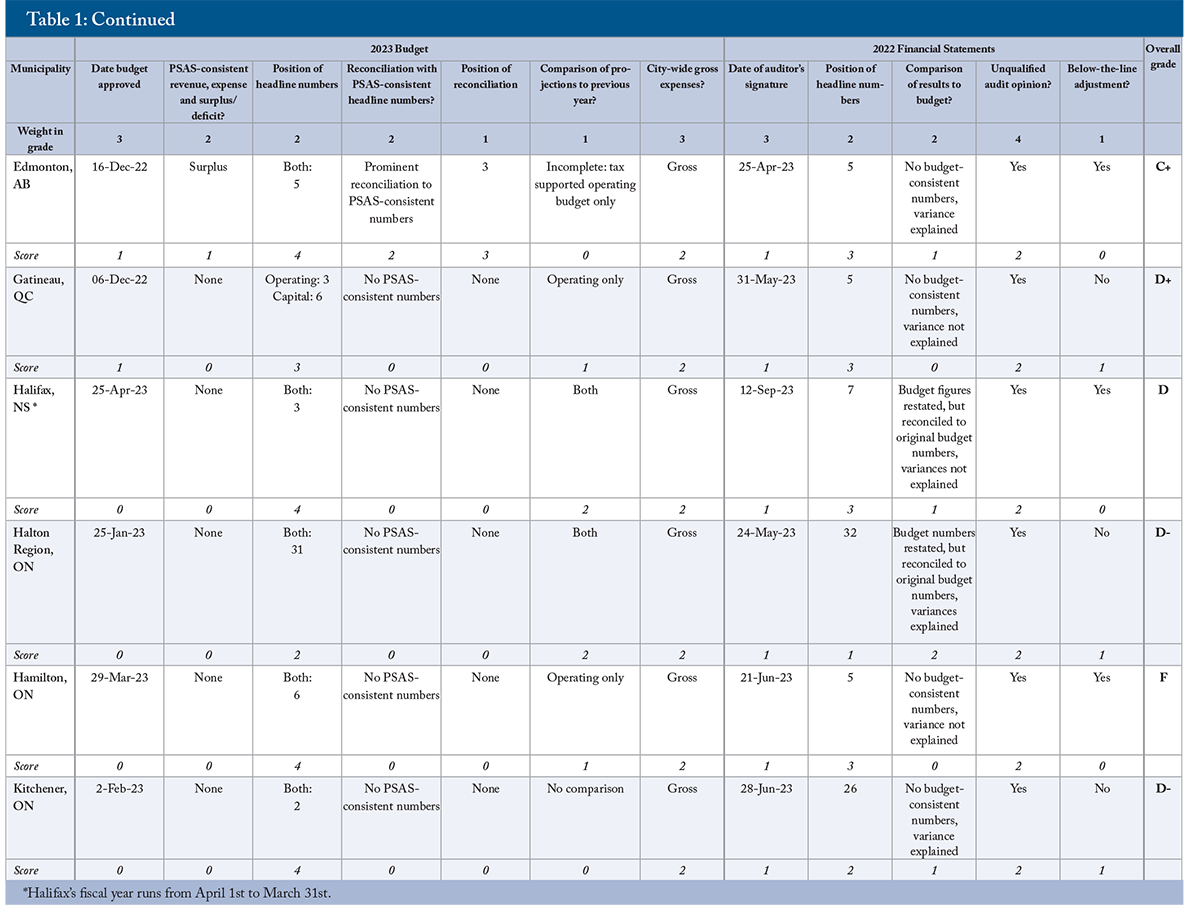

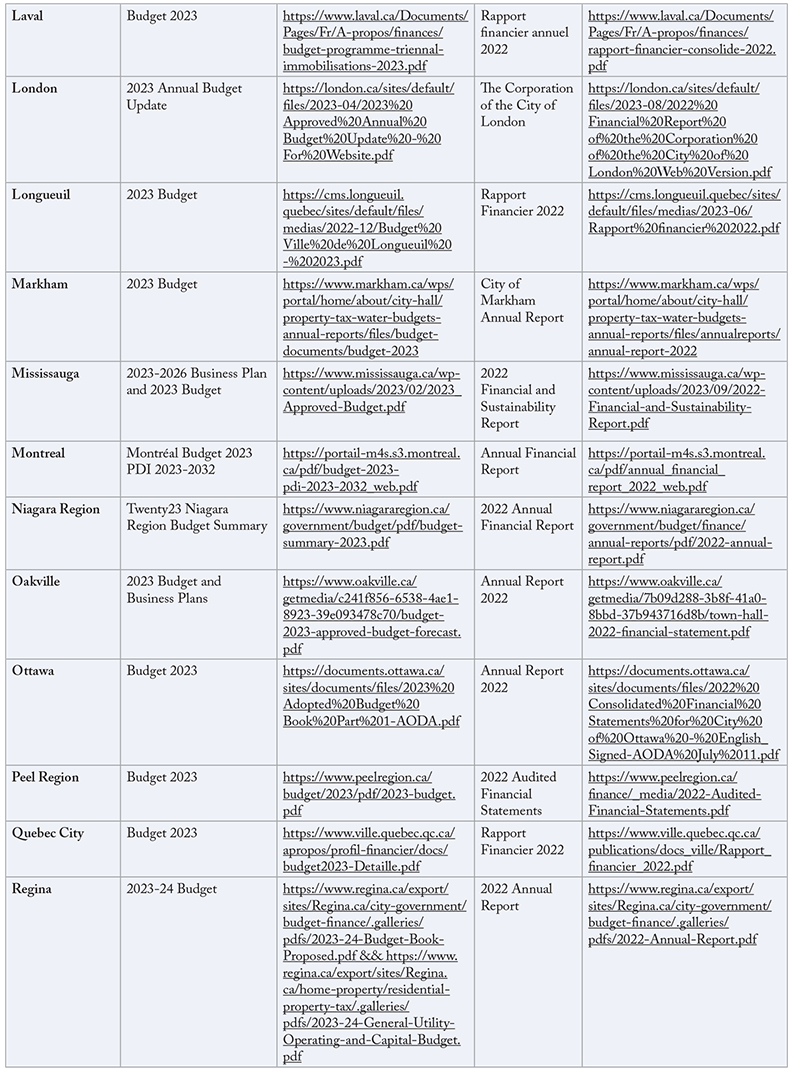

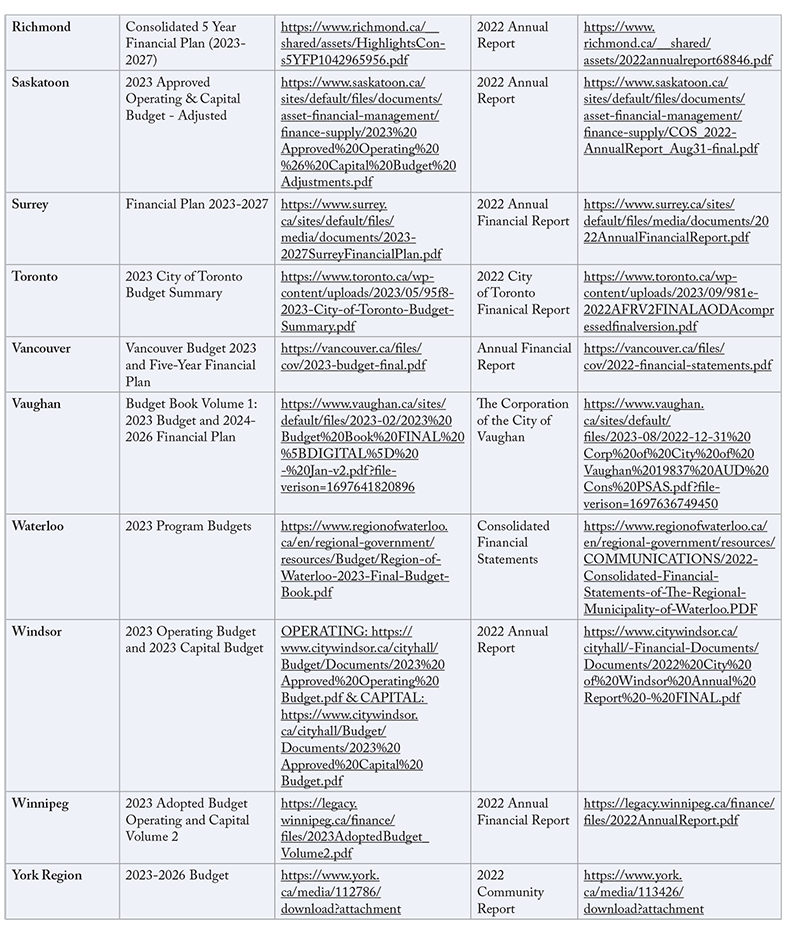

Our 2023 report card uses the points we awarded, based on the above 12 criteria (seven for their 2023 budgets and five for their 2022 annual reports or financial statements), as the basis for assessing the fiscal accountability of 26 of Canada’s most populous municipalities, and the six most populous regional municipalities in Ontario. Our grades for each are based on their 2023 round of budgets and 2022 round of financial statements.

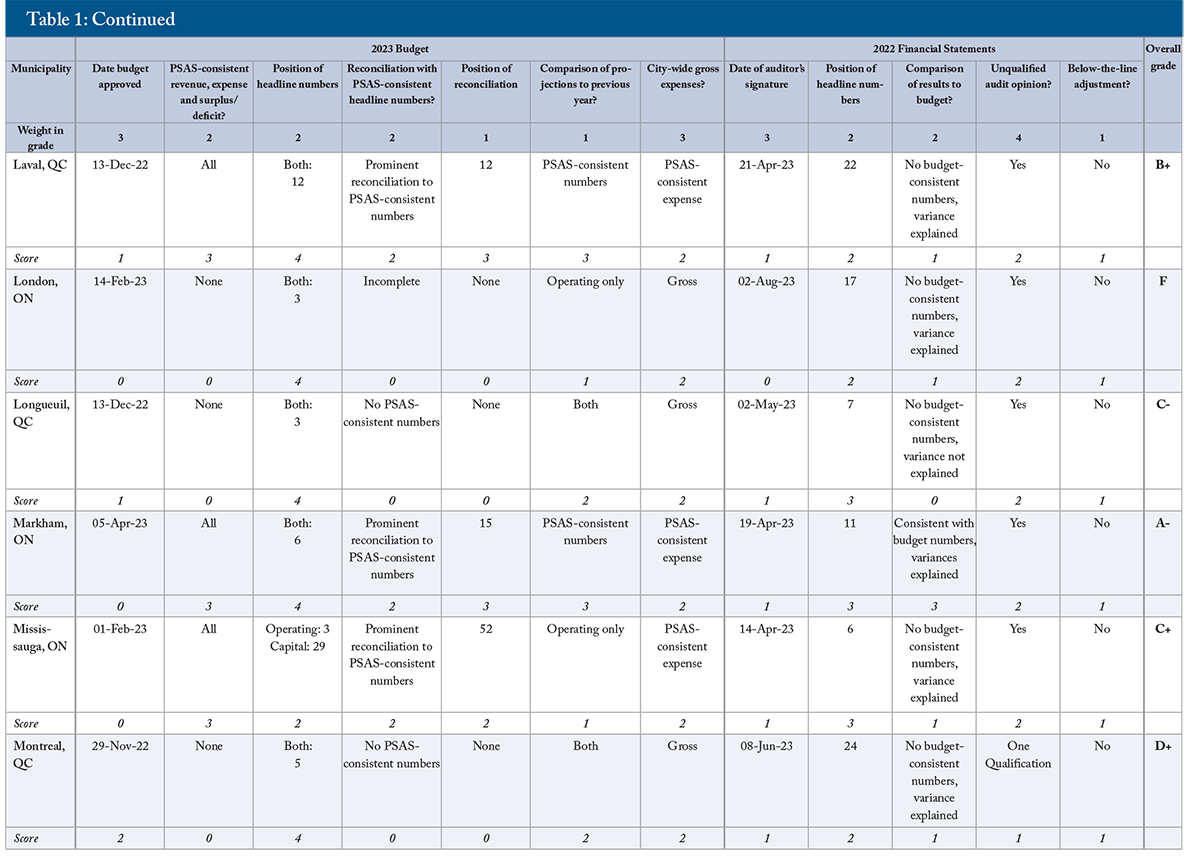

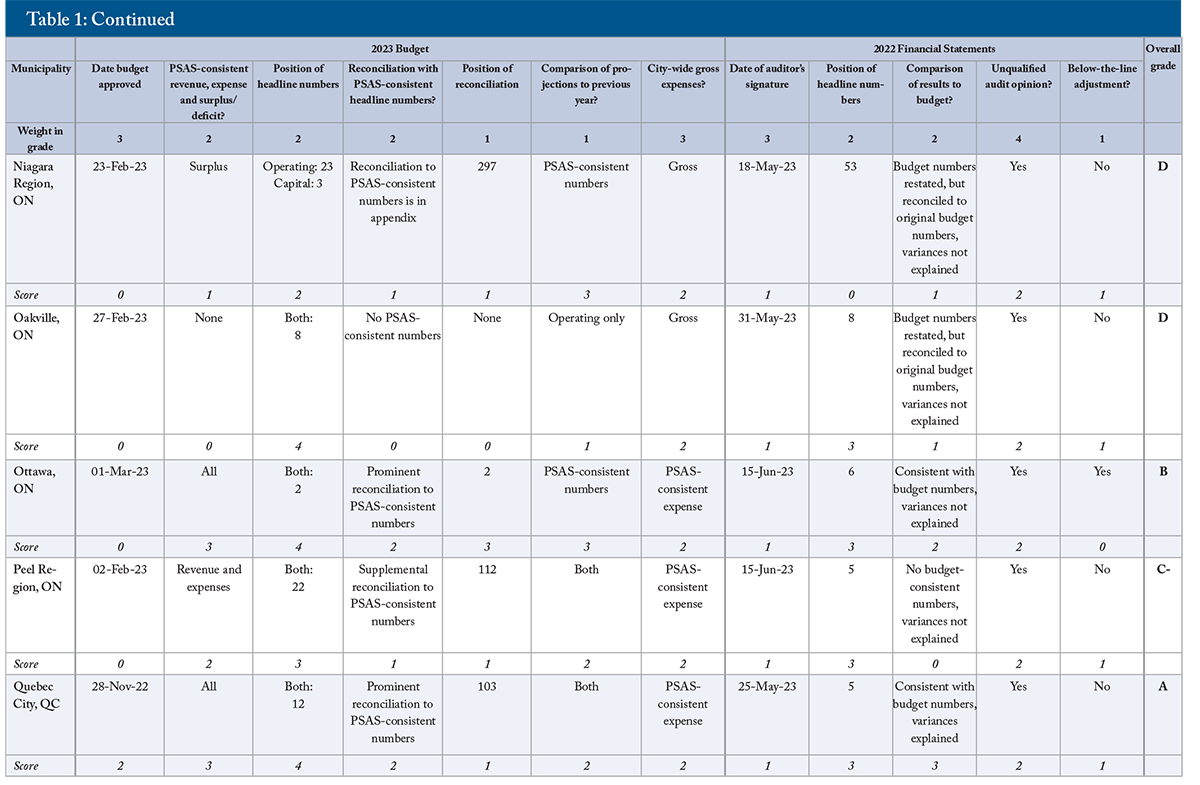

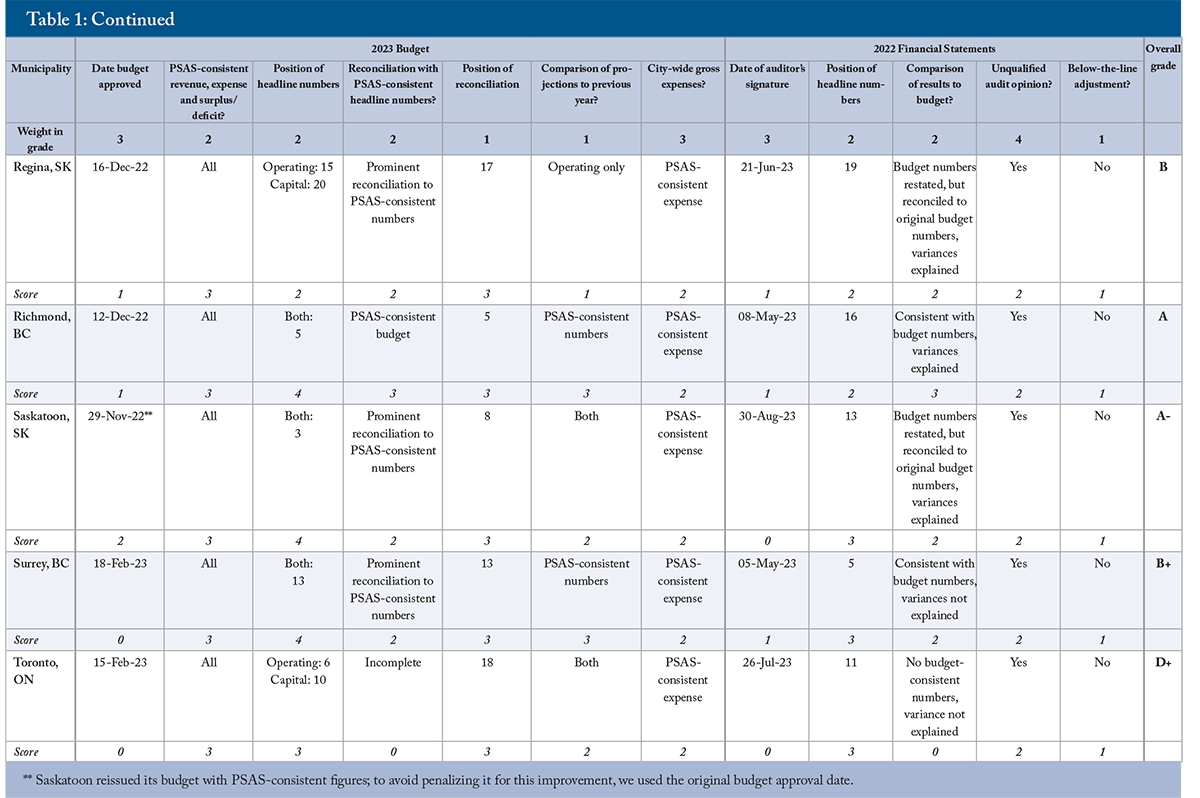

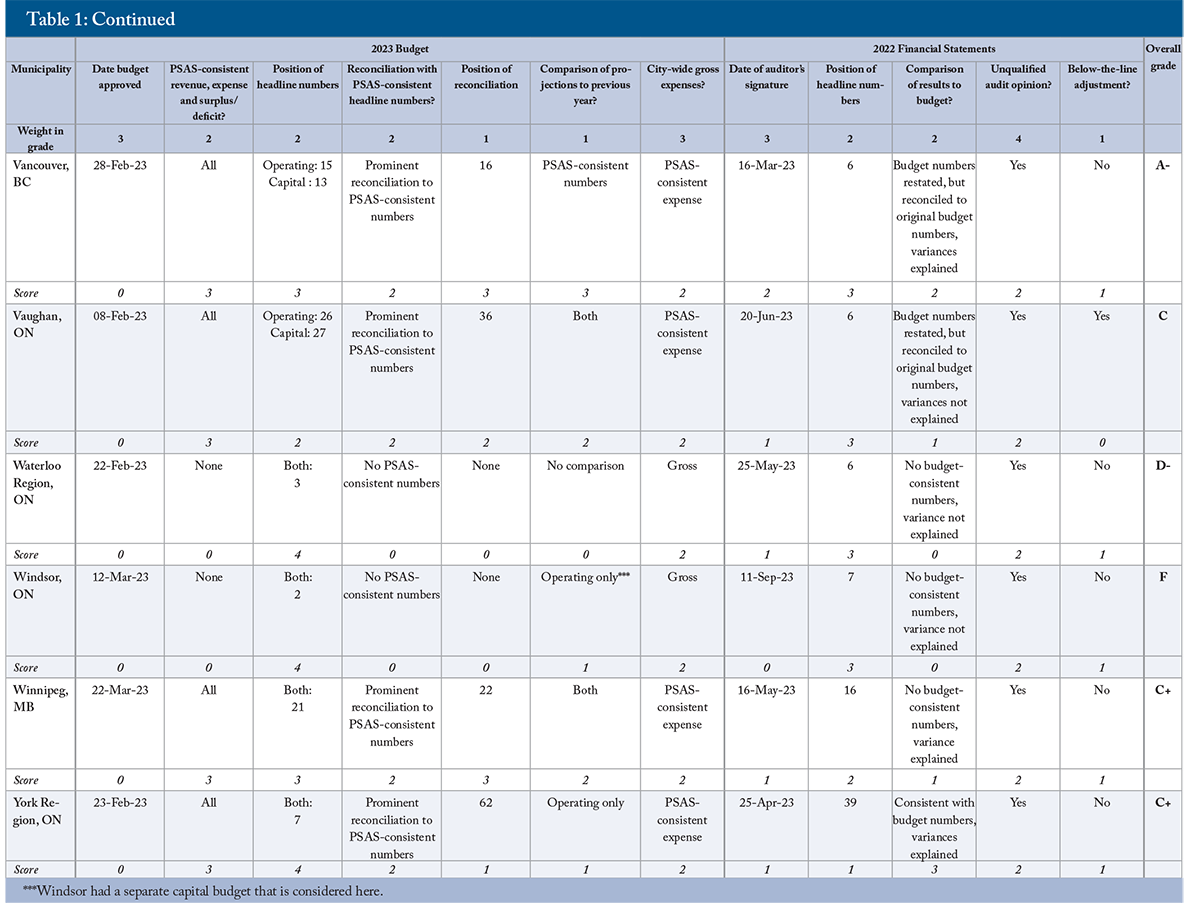

To produce an overall grade, we standardized the scores for each criterion to be between 0 and 1.8 We then weighted the standardized scores based on our judgment of the importance of each criterion to transparency and accountability, and summed the weighted scores to produce percentages. We converted the percentages to letter grades on a standard scale: A+ for 90 percent or above, A for 85–89 percent, A– for 80–84 percent, B+ for 77–79 percent, B for 73–76 percent, B– for 70–72 percent, C+ for 67–69 percent, C for 63–66 percent, C– for 60–62 percent, D+ for 57–59 percent, D for 53–56 percent, D– for 50–52 percent and F for less than 50 percent. Our assessments for each criterion and the resulting letter grades for each municipality appear in Table 1.

The Best and Worst for Financial Reporting

The results range from A to F. Too many grades are below the B tier, mainly reflecting budgets that were late and/or failed to show PSAS-consistent revenues, expenses and surpluses.

At the top of the class, with a grades of A, were Quebec City and Richmond. Both approved their budgets and financial statements promptly. Their budgets presented the headline figures up front, and prominently presented PSAS-consistent numbers – in Richmond’s case, the entire budget was PSAS-consistent. Their financial statements compared results to budget projections consistent with the figures that appeared in the budget and explained variances between projections and results.

Next came Markham, Saskatoon and Vancouver, with grades of A-. All presented headline numbers close to the start of their budgets and financial statements, and prominently presented PSAS revenue, expense and surplus within the first 30 pages of their budgets. All provided budget-to-previous budget comparisons using PSAS-consistent numbers. Their auditors signed off on their financial statements with unqualified opinions within 180 days of year-end (Vancouver’s signed off within 90 days of year-end – the best performance of any city in our survey). Their annual reports explained variances between results and projections. Markham compared results to projections consistent with the numbers that appeared in its budget, while Saskatoon and Vancouver reconciled their restated projections to their original budget numbers.

In the B range were Laval and Surrey with grades of B+, and Ottawa and Regina with grades of B, and Burnaby with a grade of B-. Each presented headline numbers early in their budgets and financial statements, and prominently reconciled headline budget numbers with PSAS-consistent revenue, expense and surplus early in their documents. Laval’s restated and unreconciled budget figures in its financial statements kept it from the A range, as did Surrey’s unexplained variances between projections and results. Ottawa’s late budget and below-the-line adjustments kept it from achieving a higher grade. Regina’s inclusion of PSAS-figures in its budget improved its grade substantially over previous years; earlier budgets and financial statements, and providing a comparison to previous years’ projections using PSAS-consistent numbers in its budget, would raise its grade further. A timelier budget would have helped Burnaby's grade.

Cities with C-range grades – Brampton, Calgary, Edmonton, Longueuil, Mississauga, Peel Region, Vaughan, Winnipeg, and York Region – typically approved budgets after the start of the fiscal year, and either did not provide PSAS-consistent revenue, expense and surplus in their budgets, or did so many pages in. Most did not compare budgets to previous years using PSAS-consistent figures – Edmonton only compared its tax-supported operating budget to the previous year – and most showed restated budget projections in the comparisons in their financial statements.

Durham, Gatineau, Halifax, Halton Region, Kitchener, Montreal, Niagara Region, Oakville, Toronto, and Waterloo Region achieved only D-range grades. All but Gatineau approved budgets after the start of the fiscal year. They either did not present complete PSAS reconciliations in their budgets or, in the case of Durham and Niagara Region, presented a PSAS-consistent surplus only in supplemental material or an appendix. Durham showed net alongside gross expenses in its budget. Toronto’s PSAS reconciliation was incomplete and misleading, including only adjustments that hurt the bottom line, and omitting those that helped it. Its financial statements were not timely. Kitchener did not compare its budget projections to previous years. Waterloo provided a comparison of budget projections to previous years, but late in the document (we also note that the 2023 budget numbers in that comparison differed from those in its main budget presentation). Halifax had below-the-line adjustments. Montreal received a qualified opinion from its auditor and the comparisons to budget projections in its annual report showed numbers different from those in the budget itself.

Hamilton, London and Windsor were at the bottom of the group with grades of F.

Hamilton’s budget was late and did not contain a PSAS reconciliation. Its financial statements showed restated budget numbers in its comparison to budget projections, did not explain variances, and had below-the-line adjustments.

London’s budget and financial statements were not timely, and its budget contained an incomplete reconciliation which did not provide PSAS-consistent revenue, expense or surplus.

Windsor did not approve its budget until March, and its external auditor did not sign its financial statements until September. Its budget contained no PSAS reconciliation, and its financial statements contained restated budget numbers and did not explain variances.

Weights in grading inevitably involve judgments on which reasonable people may differ. As a test of the sensitivity of our 2023 grades to the weights we chose, we compared those grades with an alternative method using equal weights for each criterion. That approach would produce an average absolute change across the 32 municipalities of one degree – the difference between B and B–, for example. The correlation between the rankings using weighted and non-weighted criteria is 97 percent; the correlation between the numerical grades using weighted and non-weighted criteria is 97 percent.

Notwithstanding the disappointment in the scorecard results, improvements in municipal fiscal transparency have occurred since the C.D. Howe Institute started publishing report cards in 2011 (Dachis and Robson 2011). Particularly notable has been the gradual adoption by municipalities of more PSAS-consistent numbers in budgets. These improvements have prompted changes in our scoring system.

In our 2022 report card, we simplified our criterion related to the prominence, and explanation, of reconciliations between non-PSAS-consistent and PSAS-consistent budget numbers to increase the contrast between municipalities that present PSAS-consistent numbers and those that do not (Robson and Dahir 2023). We further simplified this criterion in our 2023 report card to better contrast clear and less clear reconciliations. We also increased the weight of the criterion related to PSAS-consistent revenue and expense and the annual projected surplus or deficit in budgets, and reduced the weight on the criterion related to city-wide gross expenses. This is because the appropriate goal is PSAS-consistent budget numbers, and providing city-wide operating expenses is a poor substitute for a PSAS-consistent presentation.

We reduced the weight on the auditor’s opinion from 5 to 4. This change aligns our municipal report card better to the C.D. Howe Institute’s report card on Canada’s senior governments.

Another change this year was the stricter criterion related to budget comparisons in municipal financial statements. In the past, we awarded a point for budget comparisons, even when the comparisons contained restated budget numbers and the statements did not reconcile the restated numbers to the numbers in the budget itself. We no longer award a point in that situation.

One further adjustment in this year’s report card was the revision of the criterion for budget release dates, to award the top score to budgets approved 30 days or more before the start of the fiscal year. (Previous versions had awarded the top score to budgets approved more than 30 days before the start of the year.) This change aligns the budget release date criterion for municipalities with the criterion in the C.D. Howe Institute’s report card on Canada’s senior governments.

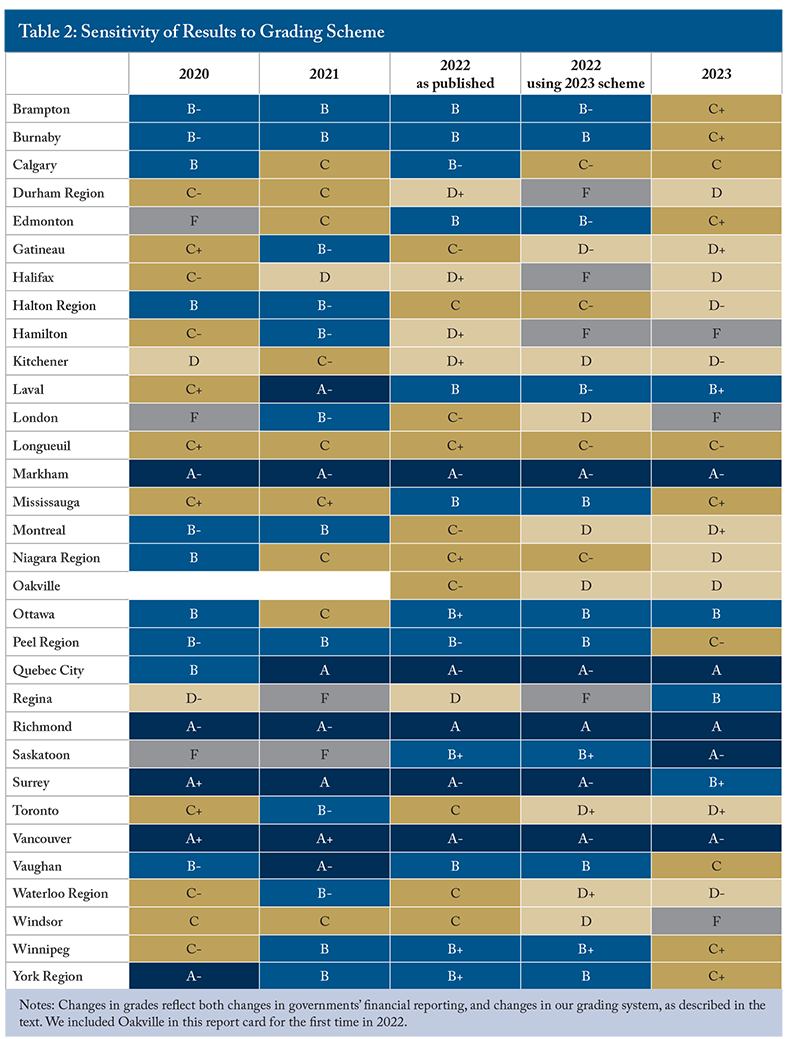

Table 2 compares the grade of each municipality in 2023 to the grades it received in previous years, showing both the grade each municipality earned in the 2022 report card and the grade it would have earned in 2022 if we had used the 2023 report card’s criteria and weights that year.

Comparing the 2023 grades to the 2022 grades each municipality would have received using the 2023 system, we see some improvements. Timelier releases of budgets helped some scores. More PSAS-consistent numbers also helped: Regina jumped to B from F by including prominent PSAS-consistent figures in its budget. Placement of numbers was also a factor: Halifax avoided an F grade by moving key numbers closer to the start of its budget.

We also see declines. Later budget presentation was a common reason for deteriorations in grades. Ontario municipalities were delayed by provincial legislation that prevents timely budget preparations after municipal elections, which occurred in late 2022. Ontario’s “Strong Mayor” legislation, which applied to Ottawa and Toronto at the time of their 2023 budgets, also specifies a late budget date. Later presentations affected some municipalities with strong records and otherwise high scores: Markham and Vancouver released their budgets after the start of the fiscal year. More than half the municipalities in our survey released their budgets later than the previous year by enough to affect their scores. Other reasons for declines were a qualified audit opinion in Montreal’s case, and a below-the-line adjustment in Vaughan’s case.

Happily, several strong performers maintained their scores in the A range. Markham and Vancouver stand out for consistently top-level results, while Quebec City and Richmond topped the class in 2023.

Does Municipal Fiscal Transparency Matter?

Timely, reliable and transparent financial reports alone cannot ensure that municipal governments will serve their citizens’ interests. However, they are an essential foundation for citizens and legislators to understand and act on problems the numbers may reveal.

Budgets that do not reconcile with financial statements impede people’s ability to compare budgeted financial plans to past actual financial results. Instead of operating with up-to-date information, most municipal councils develop their budgets with reference to past budgets – a practice that people unfamiliar with municipal governments, and even many who work in them, acknowledge makes little sense. Budgeting with reference to the last year with audited results, and estimated results for the year prior to the budget year, is better.

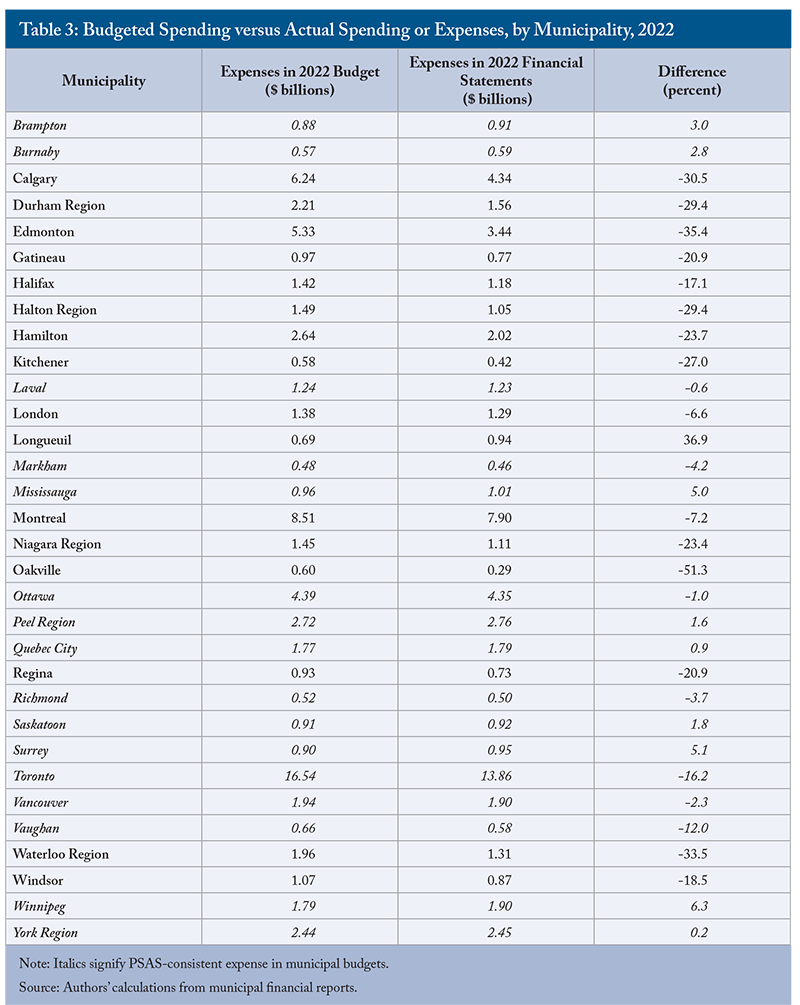

Inability to compare intentions and results reduces the attention councillors, the media and the public pay to municipal finances. Why struggle to understand a budget that experience suggests does not help you predict results? Consider what would happen if a diligent but non-expert councillor delved into a municipality’s operating and capital budgets and did what a motivated but naïve person might do to calculate spending: add the operating and capital totals together. The numbers this approach would have yielded during the 2022 municipal budget round appear in Table 3, where we compare them with the expenses reported in each city’s 2022 audited financial statements, showing the municipalities without PSAS-consistent headline budget expenses in regular font and the municipalities with PSAS-consistent expenses in italics.

To pick a dramatic example, Oakville’s 2022 budget projected $600 million in spending while its 2022 financial statements showed $290 million in expenses. For expenses to come in at less than half of projections is so weird that an expert might suspect an accounting discrepancy and start to read the fine print. A non-expert, struggling to interpret financial reports that we judge as meriting a grade of D, might think the city is incompetent or publishing meaningless numbers. Many other municipalities had discrepancies between their 2022 budgets and results that would lead a councillor who adds operating and capital together to conclude that the city’s execution or disclosure was widely off: in 5 of the 32 municipalities we examined, the gap a non-expert reader might calculate was 30 percent or more.

One would expect that the differences in Table 3 would reflect municipalities over- or underspending relative to their budget commitments – an appropriate topic for councillors to take up with staff and explain to their constituents. But many of the biggest differences reflect inconsistent accounting. Municipalities that presented PSAS-consistent budgets or very prominent PSAS reconciliations still had variances between projections and results: even well-managed businesses, households, not-for-profits and governments do not hit their budget targets exactly. But the variances of municipalities presenting PSAS-consistent budgets tend to be smaller. The average of the absolute values of the variances for the 16 municipalities that presented PSAS-consistent budgeted expenses was 4 percent; the average for the 16 that did not was 25 percent.

Aside from fostering notions that city finances are out of control or incomprehensible, discrepancies between non-PSAS-consistent budgets and PSAS-consistent financial statements create specific problems. The apparent high price tag on capital projects in municipal budgets can discourage capital investments and encourage cities to charge too much up front for the projects they undertake. Some cities, notably in Ontario, have accumulated significant deferred revenue, or reserves – money collected in advance of projects that might not be built for years, if ever.

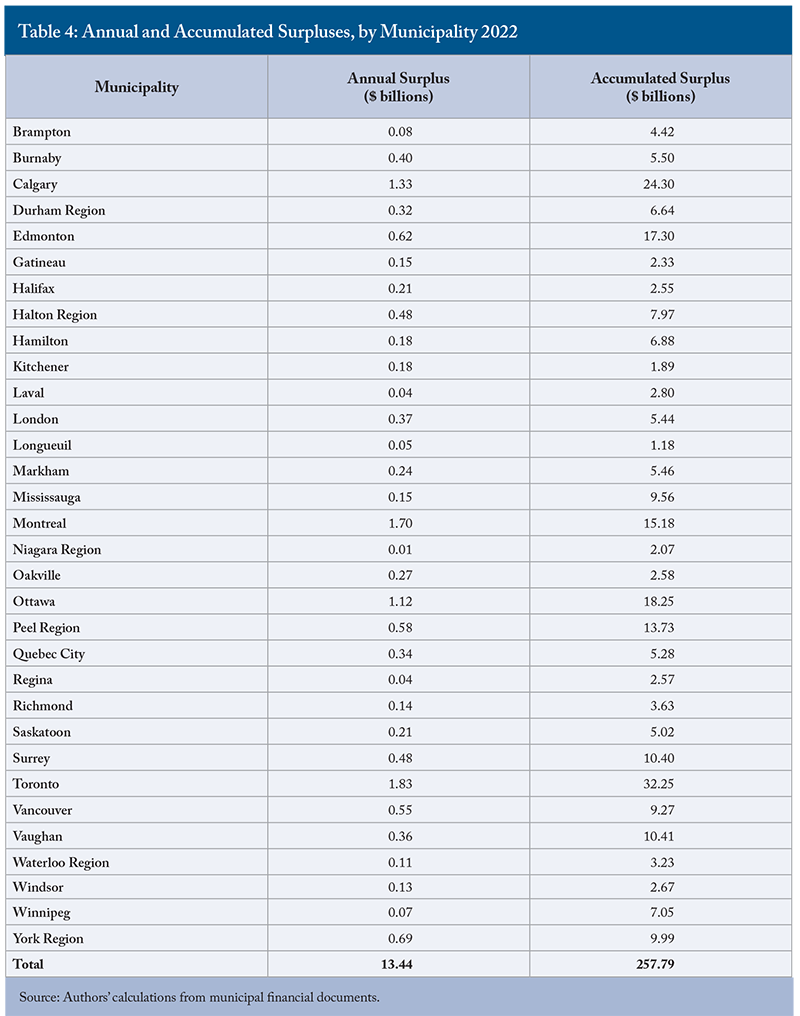

A related point is the high profile of the annual panic over balancing the city’s budget, and the low profile of the sizable annual surpluses cities typically show in their financial statements. The 32 municipalities in this survey had surpluses totaling over $13 billion in 2022 and accumulated surpluses – the measure by which PSAS intend to capture service capacity – of $257 billion (Table 4).

Cities are in better fiscal shape than most Canadians know. Councillors would probably approve infrastructure and other capital projects more readily if they had greater confidence in the capacity of their cities to deliver services in the future.

Financial Presentations Can Affect Decisions

Disagreements between governments and auditors, or other outside observers, over financial presentations show the importance of these presentations. Battles between senior governments and their legislative auditors show that governments think the presentation of financial information matters: why risk a qualified opinion unless the presentation of misleading numbers offers some political reward?9

The persistence of cash accounting in municipal budgets is partly a matter of inertia, but there is more to it than automatically repeating the previous year’s routine. Advocates of cash accounting and balanced operating budgets expect the presentations they prefer to produce different outcomes than budgets prepared in accordance with PSAS. Commenting on past iterations of this report card, some municipal officials have noted that the better-looking bottom lines in PSAS-consistent budgets might induce councillors to spend and borrow more. But shaping a budget presentation to produce a desired outcome is problematic in principle and, as just noted, can distort decisions in regrettable ways.10

Current concern about housing affordability makes one consequence of cash-based capital budgeting worth highlighting: the infrastructure charges some cities levy on developers. These charges raise the price of homes by as much as $100,000 in the Greater Toronto Area, and almost $50,000 in some cities in British Columbia (Dachis 2020). Why should new homebuyers pay these charges? The infrastructure they cover provides benefits over wider areas and longer periods. To the extent that cash budgeting for capital encourages these charges, it makes new homes less affordable.

Improving Fiscal Accountability in Canadian Cities

A motivated but non-expert councillor or taxpayer should be able to pick up a municipality’s budget and financial statements and readily find consolidated revenue and expense figures. This user should also be able to compare budget projections with past results, and financial statements results with past budget projections. The information should be timely enough to inform budget decisions and votes, and budgets should pass before revenues are collected and expenses incurred. In the past, the budgets and financial statements of most Canadian senior governments typically failed to meet these standards, but they have improved over time (Robson and Dahir 2023). Municipal budgets and financial statements have also improved, but not enough, and not consistently. How could more of Canada’s municipalities earn A grades?

Adopt PSAS-Consistent Accounting in Budgets

First, they should prepare their budgets using the same PSAS-consistent accounting they use in their financial statements. Accrual accounting would modernize municipal capital budgeting, expensing long-lived assets as they deliver services, rather than showing massive cash outlays up front and nothing later. Users of the budget would see the same consolidated measures of revenues and expenses – and the more meaningful surpluses – they see in financial statements, including all entities that the municipal government controls and that depend on it for financing.

Some municipal officials argue that cash budgeting for capital is easier for councillors to understand, and that separate presentations of tax-and rate-supported services are more meaningful for citizens. York Region’s 2023 budget argues that “the modified accrual approach gives decision-makers and other readers a clear picture of where resources are expected to come from, how much tax levy will be required, and how resources will be applied to all activities, including capital and operations to meet current and future needs” (York Region 2023, 67). However, even cities that do not present PSAS-consistent budgets have noted the superiority of the PSAS framework. Toronto’s 2021 budget stated that complying with PSAS and producing an accrual budget “provides more information as to whether the government entity… is in a better or worse position than the previous year” (City of Toronto 2021, 18). Brampton’s 2023 budget noted that “full accrual budgeting provides stakeholders with a better reflection of the long-term financial health of the municipality for decision-making purposes” (City of Brampton 2023, 46). We agree. Accrual aligns revenues and expenses and aligns costs and benefits to taxpayers and citizens better over time.

One barrier to PSAS-consistent budgets in many cities is provincial regulations. Ontario requires its municipalities to balance their operating budgets, including transfers to and from reserves. British Columbia requires its municipalities to include debt principal repayments in their spending. These requirements are holdovers from cash accounting. Other measures could constrain municipal indebtedness without mandating archaic and confusing budgets. Most provinces adhere to PSAS in their own budgets, and none object to PSAS in municipal financial statements – indeed, Quebec requires its municipalities to provide PSAS-consistent versions of their budgets to the province. Alberta’s Municipal Government Act explicitly states that a municipal budget presented in a format consistent with its financial statements satisfies

its requirements with respect to operating and capital budgets.

Notwithstanding provincial obstacles, municipalities can and should put PSAS-consistent numbers in their budgets. Richmond’s PSAS-basis budget matched its financial statements line by line, and Surrey produced PSAS-consistent numbers that were up-front, straightforward and easy to understand. All cities can, and should, be doing this. The introductions by mayors and city managers in the opening pages of a typical municipal budget are excellent places to present PSAS-consistent summaries of projected revenue, expenses and surplus.11 We underline that progress has occurred in this area over the period that the C.D. Howe Institute has produced these reports. In 2010, not one municipality in our survey provided any PSAS-consistent revenue, expense, and/or surplus/deficit numbers in its budget. In 2023, 20 did. We look forward to reporting further progress in the future.

Present Formal Complete Budgets for Council Approval Every Year

Some cities do not present formal budgets each year, instead producing partial updates to previous multi-year plans. These updates are not a substitute for a single document that shows consolidated revenue and expense and the bottom line, with meaningful breakdowns of major revenue sources and programs, for the upcoming year. All cities should present, and councils should vote on, formal annual budgets.

Provide Comprehensive Consolidated Annual Revenue, Expense and Surplus/Deficit Figures

Although PSAS prescribe single figures for consolidated revenue and consolidated expenses, and an annual surplus or deficit that reflects the difference between the two, municipal budgets commonly separate fee- and tax-supported services. Consolidated figures are better: they provide a more complete picture of a city’s operations and their implications for its future capacity to deliver services.

Showing consolidated figures in no way restricts a city’s ability to adjust rates and property taxes. Budgets can also show the split between costs households can control – by using less water, for example, or smaller garbage bins – and taxes they cannot. Indeed, cities can show the same operating and capital budgeting information they do now, if the constituencies for those presentations continue to demand them. But those numbers should be supporting information – supplements to, not substitutes for, PSAS-consistent numbers.

As for municipalities’ bottom lines, provinces that wish to constrain their municipalities’ borrowing can do so through other means, without mandating departures from PSAS in budgeting. As we have noted already, most senior governments adhere to PSAS in their budgets as well as in their financial statements. Municipalities should do the same, to give users vital information in a widely understood format.

Limit Below-the-Line Adjustments

Whatever the justifications for below-the-line entries, they drive a wedge between a city’s annual surplus and the change in its accumulated surplus over the year. Budgets do not anticipate them and most users ignore them, making them obstacles to accountability. If owning a utility or other investments is affecting a municipality’s capacity to deliver services, a below-the-line negative adjustment is appropriate, but it is opaque, and discourages a conversation that might be useful. How about managing it better, or disposing of it?

Present Key Figures Early and Unambiguously

No one, however expert, should have to dig through dozens or even hundreds of pages of a document or slide deck to find a municipality’s consolidated revenue, expenses and surplus or deficit. Nor should a user come across more than one candidate for these numbers and wonder which is correct. The summary in Table 1 makes the search for key numbers in municipal budgets seem simpler than it is. We invite readers to check the budget documents produced by their own municipalities. Too often, the search will involve multiple hyperlinks, reams of pages and many graphically highlighted numbers that look like the right ones but are not.

Early and unambiguous presentation is easy. Among senior governments, Newfoundland and Labrador has problems with elements of its budgets and financial statements, but it topped the class for putting its key consolidated figures on page 2 of its 2023/24 budget. The key consolidated figures in its 2022/23 public accounts appeared on page 11. Municipalities can do the same. Vancouver’s 2022 annual report showed its year-end results on page 5. Such prominent display is a huge aid to councillors, the media and taxpayers.

Show and Explain Variances between Results and Projections

Municipalities should reconcile their year-end results with their budget projections, using common accounting methods, consistent numbers and informative commentary. Different accounting and inconsistent numbers are formidable obstacles even to expert users, and will stymie non-experts at the outset. We also encourage municipalities to follow the valuable practice of the federal and many provincial and territorial governments and publish in-year reports that, using PSAS-consistent accounting, compare interim results to budget plans.

Publish Timely Budgets and Financial Statements

Prompt approval of budgets and timely publishing of audited financial statements are key elements in accountability. Councillors should approve spending before it occurs, and should have timely information on the year under way when they start their discussions of the next year’s budget.

Municipalities that use a calendar year for financial accounting and reporting purposes should vote on their budgets well before January 1. Ontario’s Municipal Act prevents municipalities from approving a budget for the year following an election in the same year as the election. As a result, Ontario’s 2022 municipal elections prevented Ontario municipalities from presenting their 2023 budgets until after 2023 had started. Some Ontario municipalities did not approve their budgets until February, March or even April – not consistent with legislative control of public funds. That is a prominent example of a law that needs revision. Ontario’s “strong mayor” law, which specifies February 1st for budget presentations, will apply to all non-regional municipalities in Ontario in this survey. This law needs revising – while the other municipalities could present budgets before the fiscal year starts, too many are likely to follow the lead of Ottawa and Toronto, and present budgets late.

One potential reform would be for other provinces to join Nova Scotia in aligning the fiscal years of their municipalities with those of the province: from April 1 to March 31. That would alleviate the temptation for municipalities to delay budget finalization until they know more about transfers and other provincial fiscal actions. Unless or until that happens, municipalities must simply do the best they can. Waiting for the provincial budget guarantees that a large share of the municipality’s spending will occur without legislative authorization.

Municipalities that use a calendar year for financial accounting and reporting purposes should publish their financial statements before April 30. Alberta requires its municipalities to release their statements by May 1 – a deadline Calgary and Edmonton are clearly able to meet.

The Finances of Canada’s Municipalities Should Be More Transparent

Municipalities provide critical services to most Canadians and absorb a commensurately large share of Canadians’ incomes. Councillors need clear information about their municipality’s finances if they are to hold officials to account, and taxpayers and voters in turn need it to hold councillors to account. The effects of a slowing economy on revenues, pressure on spending from demands for housing and infrastructure, and constrained finances of senior governments will likely cause financial stresses for municipalities in the years ahead. Good understanding of, and intelligent debate about, municipal finances can only help.

The budgeting practices of most major Canadian municipalities should support that engagement more than they do. PSAS-consistent budgets that users can compare easily with their subsequent financial statements, as well as financial information that is more accessible and timely, would help raise the financial management and fiscal accountability of Canada’s cities to a level more in line with their importance in Canadians’ lives.

Appendix: Reference Tables

References

City of Brampton. 2023. Budget. December.

City of Toronto. 2021. Budget. February.

York Region. 2023. Budget. February.

Dachis, Benjamin. 2020. Gimme Shelter: How High Municipal Housing Charges and Taxes Decrease Housing Supply. Commentary 584. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. November.

Dachis, Benjamin, and William B.P. Robson. 2011. “Holding Canada’s Cities to Account: An Assessment of Municipal Fiscal Management.” Backgrounder 145. C.D. Howe Institute. November.

International Budget Partnership. 2020. “The Open Budget Survey, 2019.” Washington, DC. March.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2002. “OECD Best Practices for Budget Transparency.” Paris.

OSC (Ontario Securities Commission). 2023. “Filing Due Dates Calendar for Annual and Interim Filings by Reporting Issuers.” Available at https://www.osc.ca/en/industry/companies/reporting-issuer-and-issuer-fo…, accessed October 12.

PSAB (Public Sector Accounting Board). 2018. “Statement of Concepts: A Revised Conceptual Framework for the Canadian Public Sector.” Toronto. May.

———. 2021. “Financial Statement Presentation, Proposed Section PS 1202.” Toronto. Exposure Draft. January.

Robson, William B.P. 1999. “The $22.5 Billion Question: Will Exposure Make Future Federal Surpluses Evaporate?” Backgrounder. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. October 27.

———. 2019. “Does Accounting Drive Budget Decisions? The Strange Case of the Toronto Subway ‘Upload’.” C.D. Howe Institute Intelligence Memo. September 20.

Robson, William B.P., and Miles Wu. 2021. Good, Bad, and Incomplete: Grading the Fiscal Transparency of Canada’s Senior Governments, 2021. Commentary 607. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. September.

Robson, William B.P., and Nicholas Dahir. 2023. The ABCs of Fiscal Accountability: The Report Card for Canada’s Senior Governments, 2023. Commentary 646. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. October.

- 1 The C.D. Howe Institute’s annual report card on the financial documents of the federal, provincial and territorial governments also reflects these important themes in the framework of the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB 2018, 2021). Both the senior government and municipal government report cards complement international measures of fiscal transparency such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Best Practices for Budget Transparency (OECD 2002) and the Open Budget Survey (International Budget Partnership 2020).

- 2 Cash received for capital projects, including transfers from other levels of government, should not come into income until the related expenses – including amortization of the project – are recorded. We stress this point because some critics of this report card have objected that PSAS do not allow this treatment and that municipalities therefore should not use accrual accounting in budgets. In fact, PSAS do allow this treatment, which makes sense in budgeting and in reporting.

- 3 Web pages can change without clear dates, making verification hard. Links can create navigation challenges for users that do not lend themselves to quantification in a scoring system.

- 4 When operating and capital subtotals appeared on different pages, our score on this criterion reflects the later page.

- 5 In principle, a PSAS-consistent budget can project either a surplus or a deficit. In practice, the municipalities we looked at projected surpluses when they presented complete PSAS-consistent numbers in their budgets, and recorded surpluses on a PSAS-basis in their financial statements.

- 6 Quebec amalgamated several municipalities, including Gatineau, Laval, Longueuil, Montreal and Quebec City, in the early 2000s. Municipalities that are part of a larger agglomeration typically present numbers for themselves and the larger entity. We awarded 2 on this criterion to municipalities that showed both with equal prominence, since both numbers help users understand the scope and cost of municipal operations.

- 7 Our approach is arguably too lenient, but holding the municipalities to the same standard we apply to senior governments would produce zeros across the board on this criterion. We look forward to the day when more PSAS-consistent budgets that show prior actual results will allow us to adopt a system that better rewards good practices in this area.

- 8 For example, a 1 on a criterion with a maximum score of 2 yields a standardized score on that criterion of 0.50; a 1 on a criterion with a maximum score of 3 yields a standardized score of 0.33. Maximum scores include the additional point awarded for having operating and capital totals on the same page in budgets, and for explaining variances between results and projections in financial statements.

- 9 A salient senior-government example occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s when Ottawa prebooked large amounts of spending, artificially reducing surpluses (Robson 1999; Robson and Wu 2021). More recently, the auditors general of Ontario and Quebec objected to presentations that reduced these provinces’ reported annual and accumulated deficits (Robson and Dahir 2023).

- 10 Accounting’s potential to shape policy was clear when Ontario’s 2019 budget anticipated a provincial takeover of the Toronto subway. Although the province can support municipal investments with transfer payments, the budget said “provincial ownership of the assets would allow the Province to amortize its capital contributions.... This ownership transaction ultimately creates the fiscal space to allow the Province to significantly deepen its commitment to transit and start projects immediately, not sometime in the distant future.” The illusion that the subway was cheaper to build if provincially owned only existed because the city of Toronto did not budget capital on an accrual basis (Robson 2019). The proposal failed on other grounds, but would never have come forward at all if Toronto had budgeted using PSAS.

- 11 Modern financial statements include a schedule of changes in cash. Governments that wish to highlight cash transactions and balances can provide such schedules pro forma with their budget and provide reconciliations with the budget plan in their financial statements.