The Study In Brief

New innovations are emerging to address the shortcomings of the “poor cousins” among employer-sponsored pension plans – defined-contribution (DC) plans and Group RRSPs. Unlike defined-benefit (DB) plans, they do not provide retirement income for life but instead focus on the accumulation phase. It’s time to put the “pension” back in these plans, which are known as capital accumulation plans (CAPs).

With over $1.5 trillion in assets, the growing prevalence of membership in DC pensions specifically and the continued growth of contributions to them (nearly doubling the pace of growth of contributions to DB programs) makes it even more important to improve retirement plan outcomes from CAPs over the next decade. This improvement will depend critically on meeting the challenges of the decumulation phase – that is, once employees stop accumulating and start drawing down.

This Commentary examines the challenges of decumulation for employees, current practices and options, as well as proposed new options. We believe the time is right for regulators, program sponsors and industry stakeholders to embrace what seems to have been lost along the way: DC and Group RRSP programs are not primarily about accumulating capital; rather, they have always been intended to – and, in fact, can – provide working Canadians with lifetime retirement income…when done right.

However, saving and investing on autopilot during the accumulation portion of their retirement journeys has left participants ill-prepared to deal with the exceedingly challenging requirements of restructuring their assets at the point of retirement when they seek a lifetime of retirement income.

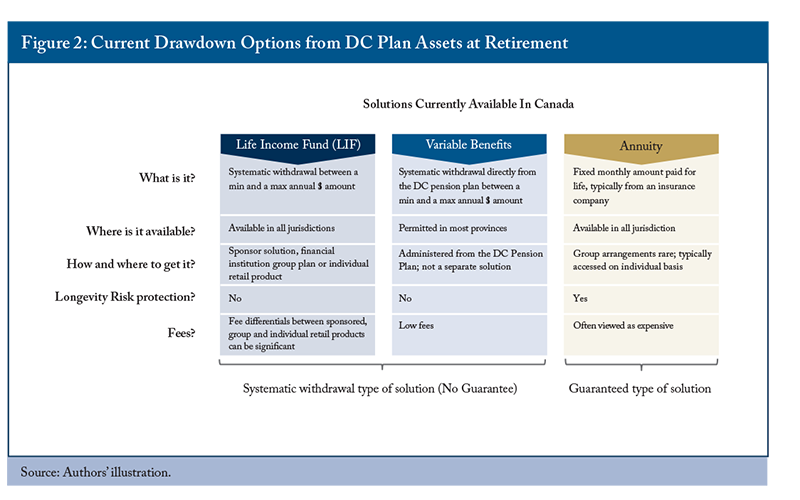

Currently, Canadians have three options to draw down income from their CAP assets at retirement.

- An investment account with withdrawal options, such as LIFs for locked-in assets originating from DC pensions, or RRIFs for unlocked assets originating from Group RRSPs. Critically, they do not provide any guarantees or longevity protection; consequently, there is a risk that assets might be depleted prematurely.

- Variable benefits accounts within DC registered pension plans that allow for gradual income withdrawals on a similar basis to LIFs, but that take advantage of the scale and legal structure of DC pension plans.

- Annuities sold by insurance companies. These are the only vehicles broadly available today that provide income guarantees and longevity protection. These products, however, are often viewed as expensive and inflexible and are purchased by relatively few retirees today.

In 2021, the Canadian Income Tax Act and regulations were amended to permit two new vehicles: Variable Payment Life Annuities (VPLAs) and Advanced Life Deferred Annuities (ALDAs). If adopted in pension legislation and by the industry, these new vehicles could significantly enhance the options available.

A VPLA fund within a DC pension plan converts the account balance of a retiring employee who elects this option into a monthly pension payable for the remainder of the retiree’s lifetime, based on assumptions about investment and mortality experience. The retiree’s monthly pension amount is variable in that it is adjusted periodically to reflect the actual mortality and investment experience of the pool of retired employees who elect the VPLA option.

An ALDA also provides a guaranteed lifetime annuity, but payment from the ALDA can begin as late as the end of the year the individual turns age 85. No more than 25 percent of the individual’s DC account balance can be used to purchase an ALDA. In addition, no more than $150,000 (indexed to inflation) in aggregate from all of an individual’s registered account balances can be used to purchase an ALDA.

One of the main differentiators between large DB plans and most of today’s CAPs is their ability seamlessly to provide lifetime retirement income and, ideally, to pool longevity risk. The adoption of decumulation features inspired by the DB world within CAPs, with or without longevity-pooling features, can have a substantial impact on this shortcoming. These programs can and should deliver lifetime pensions and not just accumulated assets for plan members.

The authors thank Alexandre Laurin, William Robson, Charles DeLand, Keith Ambachtsheer, Randy Bauslaugh, Kathryn Bush, Derek Dobson, Malcolm Hamilton, Eric Monteiro, James Pierlot, anonymous reviewers and members of the Pension Policy Council of the C.D. Howe Institute. The authors retain responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

As executives at LifeWorks, the authors advise clients on pension issues.

Introduction

When Canadians hear the term “defined benefit” (DB), most recognize it immediately and translate it to the concept of a workplace “pension.”

Defined-contribution (DC) pension plans and Group Registered Retirement Savings Plans (Group RRSPs), both of which are often referred to as capital accumulation plans (CAPs), on the other hand, do not often get the same welcome recognition and are sometimes considered the poorer cousin in retirement circles. Perhaps this is because these programs were positioned to emphasize the concept of “capital accumulation” over that of delivering retirement income or “pensions” for their participants.

Large DB programs can deliver pension income at an economical cost in large part because of their ability to provide effective longevity risk pooling, although other factors are also important, including their ability to leverage their scale to access higher-quality investments for lower fees and long-term strategic asset allocation with access to broad investment opportunities. These aspects are largely absent from most CAP programs; fortunately, however, that landscape is slowly shifting, with a few solutions emerging that might be more effective at offering similar benefits.

Much has been written about the decline in private sector pension plan coverage in Canada. According to Statistics Canada, as of January 1, 2019, only 23 percent of private sector employees were covered by any kind of pension plan, either DB or DC, down from 27.7 percent in 1998 (Statistics Canada 2020). Members in DC registered pension plans numbered nearly 1.2 million, accounting for 18.6 percent of all Registered Pension Plan (RPP) membership. What is lesser known is that CAP programs are the fastest-growing segment of the retirement landscape in Canada and that, outside the public sector, they represent the bulk of Canadians’ retirement savings. With over $1.5 trillion in assets – according to recently tabulated sources from Statistics Canada (MacDonald et al. 2021) – the growing prevalence of membership in DC pensions specifically and the continued growth of contributions to them (nearly doubling the pace of growth of contributions to DB programs) makes it even more important to improve retirement plan outcomes from CAPs over the next decade. This improvement will depend critically on meeting the challenges of the decumulation phase – that is, once employees stop accumulating and start drawing down.

The decumulation debate has captured the attention of retirement industry stakeholders for well over a decade. It is seen by many in the retirement industry as the missing link to improving retirement outcomes for CAP participants. Yet progress has been slow.

This Commentary examines the challenges of decumulation, current practices and options, as well as proposed new options. We believe the time is right for regulators, program sponsors and industry stakeholders to embrace what seems to have been lost along the way: DC and Group RRSP programs are not primarily about accumulating capital; rather, they have always been intended to – and, in fact, can – provide working Canadians with lifetime retirement income…when done right.

The Challenges of Decumulation

As participation in CAP programs has grown in recent years, plan sponsors have taken a greater interest in improving retirement outcomes for their participants. Most of the improvements have happened in the accumulation phase. For example, new member onboarding and engagement tools have been developed to facilitate and encourage enrolment, while communication campaigns and customized decision support tools have been used to nudge participants toward more effective choices and more competitive fees have gradually improved net investment returns.

In addition, significant efforts in the past decade have focused on selecting effective investment defaults for these plans, taking advantage of plan participant inertia to produce better results in the absence of positive actions taken by participants to select investment funds. The increasing adoption of Target Retirement Date funds to manage participants’ assets is a prime example of this approach.

The introduction and widespread adoption of Target Retirement Date funds and other “pre-built” investment portfolio solutions have prompted a shift in education strategies. The approach to members’ education has shifted away from the fundamentals of portfolio management and investment selection toward a more behavioural view of planning that emphasizes lifestyle spending requirements and the level of annual savings that are manageable and that are required to achieve them.

Ironically, this shift, which is serving employed participants well by encouraging them to leave many of the more technical aspects of saving and investing on autopilot during the accumulation portion of their retirement journeys, has left participants ill-prepared to deal with the exceedingly challenging requirements of restructuring their assets at the point of retirement when they now seek a lifetime of retirement income. This is the fundamental challenge of decumulation.

From the perspective of most CAP members, the environment in which asset accumulation takes place – where an abundance of support is available – could not be more different than the conditions under which decumulation typically takes place today.

Throughout the accumulation phase, most members are absolved of many decisions and much responsibility through the actions of an engaged plan sponsor. They are offered institutional investment options – often in the form of diversified pre-built portfolios that relieve participants of the need to develop an asset mix, rebalance their assets or to have a risk-management strategy. They benefit from competitive fees negotiated by the sponsor for the program, leveraging the assets of the group, in addition to online tools, call centre support and in-person education.

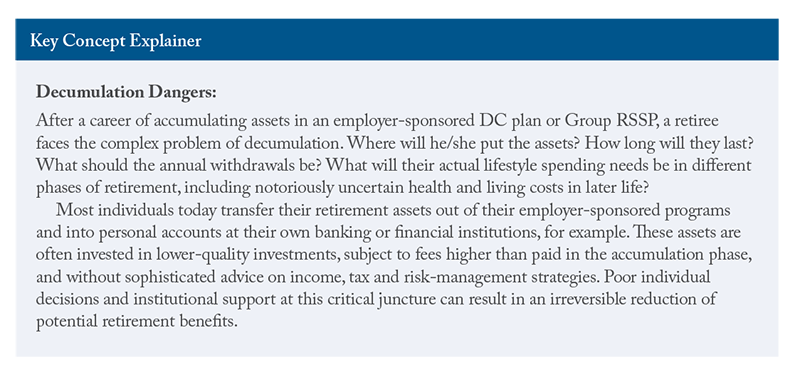

This highly supported accumulation environment stands in stark contrast to the experience most retiring plan members face. Decumulation can be a far more complex problem to solve as individuals attempt to coordinate what might be many disjointed (and separately regulated) pots of retirement assets, and to design a decumulation strategy that aligns with actual lifestyle spending needs in different phases of retirement, including notoriously uncertain health and living costs in later life. The complexities do not stop there. Retirees need to juggle many other considerations, including:

- tax efficiency (for example, the timing of withdrawals or the maximizing of tax provisions such as spousal income splitting;

- the age at which it is best to claim government pensions (Quebec/Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security);

- converting to Registered Retirement Income Funds (RRIFs) and life income funds (LIFs);

- using home equity and Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) effectively;

- maximizing income-tested government tax credits and programs such as the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS);

- dealing with market fluctuations and inflation risks;

- selection and oversight of products and advisors; and

- dealing with longevity risk – the enormous unpredictability of how long individuals might require their pension income to last – possibly the most insoluble of retirement income challenges.

No wonder Nobel Prize winner William Sharpe described decumulation or retirement income planning as the nastiest problem in finance. In Chapter 21 of his digital text book, Retirement Income Analysis, first published in 2017, Sharpe succinctly summarizes the challenge: “If there is any conclusion to be reached after reading the prior twenty chapters it is this: comprehending the range of possible future scenarios from any retirement income strategy is very difficult indeed, and choosing one or more such strategies, along with the associated inputs, seems an almost impossible task.”

Given the numerous difficulties involved in the decumulation phase, it is not surprising that CAP retirees might not always achieve optimal results. In our own experience in consulting to CAP sponsors, most individuals today transfer their retirement assets out of their employer-sponsored programs and into personal accounts at their own banking or financial institutions, or into the personal account solutions offered by the program’s recordkeeper. This is true whether the assets being transferred are coming from a DC registered pension plan, in which case they usually transfer into what is referred to as a “locked-in RRSP” or “locked-in retirement account” depending on the jurisdiction of the originating DC pension, or from a Group RRSP, in which case the assets transfer to an individual RRSP account. Others might see their accounts automatically transferred to these products if they do not make an active decision within a certain timeframe. These assets are often invested in lower-quality investments, subject to fees higher than paid in the accumulation phase, and without sophisticated advice on income, tax and risk-management strategies. Plan sponsors often do not realize that poor individual decisions and institutional support at this critical juncture can result in an irreversible reduction of potential retirement benefits.

Any discussion of the challenges of decumulation would be incomplete without a discussion of possibly the most daunting of all retirement challenges: managing longevity risk. Longevity risk is the risk that a retiree will run out of retirement savings before dying. Many Canadians do not have a good understanding of the importance of longevity risk, even though it is one of the most significant risks a retiree will face in the management of retirement assets.

The key difficulty associated with longevity risk is that it is impossible for retirees to predict how long they will live. An individual’s life expectancy depends on many factors, including health status, lifestyle, education, socioeconomic status and future mortality trends. For example, according to a Statistics Canada (2020b) report, a female age 65 with a university education or equivalent had a life expectancy four years longer than a female with less than secondary school graduation (Statistics Canada 2020a). In addition, a retiree’s “life expectancy” is just an average, reasonably stable for a large group of similar individuals, but does not predict how long any particular individual will live.

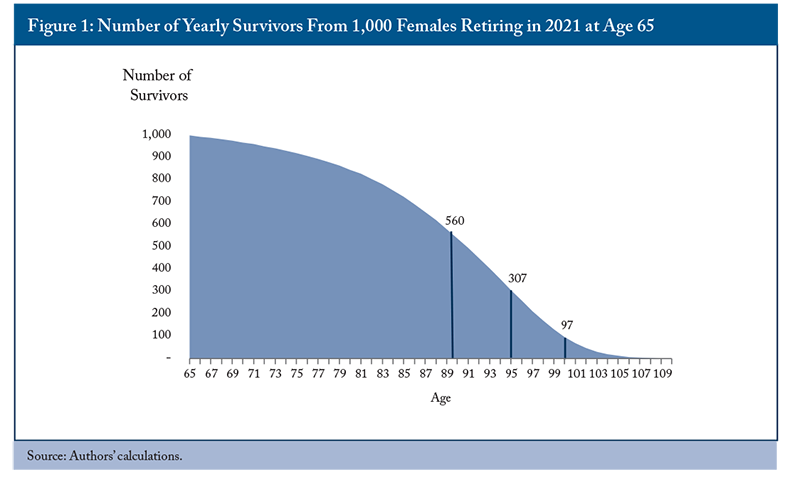

Figure 1 shows, based on the mortality table commonly used by pension actuaries,

From the 1,000 females who retire at age 65, 560 (over half) are expected to still be alive at age 89½. Also, 307 of the retirees are expected to live to at least age 95, and 97 of the retirees are expected to live to at least age 100.

Therefore, if the retiree manages her financial resources in retirement such that she will have sufficient retirement income to last only until age 89½ (her average life expectancy), there is more than a 50 percent chance that she will outlive her retirement savings, and almost a 10 percent chance that she will outlive them for more than 10 years. On the other hand, if she decides to spend less during retirement so that she has sufficient financial resources to last until age 100 or more, she has a 90 percent probability of having reduced her standard of living unnecessarily. This presents a catch-22 for any individuals trying to manage their own longevity risk – they either run a material risk of outliving their savings or they reduce their standard of living below what they likely could have afforded.

Although longevity risk is very difficult to manage at the individual level, it is more stable and predictable at the group level. In fact, it tends to be highly diversifiable across a population, lending it very well to a pooling solution (DB pensions largely operate on this principle). Given the immense difficulty individuals have in managing longevity risk in the absence of longevity pooling, we devote some attention in the remainder of the Commentary to the difference between decumulation programs that include elements of longevity pooling and those that do not.

Current Decumulation Options

Canadians currently have three options to draw down income from their CAP assets at retirement (see Figure 2):

- An investment account with withdrawal options, such as LIFs for locked in assets originating from DC pensions or RRIFs for unlocked assets originating from Group RRSPs. These can either be available on an individual basis (from a financial institution or service provider) or through a group arrangement from a plan sponsor as a component of the retirement program. These plans provide income through withdrawals of assets as permitted between annual minimum (RRIFs and LIFs) and maximum percentages (LIFs only) set under legislation. Critically, they do not provide any guarantees or longevity protection; consequently, there is a risk that assets might be depleted prematurely.

- Variable benefits accounts within DC registered pension plans that allow for gradual income withdrawals on a similar basis to LIFs, but that take advantage of the scale and legal structure of DC pension plans and do not require the transfer of assets to another vehicle. The same minimum and maximum percentages that apply to LIFs apply to these as well and, similarly, they do not provide any guarantees or longevity pooling.

- Annuities sold by insurance companies. These are the only vehicles broadly available today that provide income guarantees and longevity protection. These products, however, are often viewed as expensive and inflexible and are purchased by relatively few retirees today. In fact, according to MacDonald et al. (2021, 12), “a mere $7.6 billion in 2020” of in-force individual annuities were reported as part of statutory reserves among Canada’s insurers, representing less than one-half of 1 percent of total retirement assets in Canada (based on assets reported by Statistics Canada, Survey of Financial Security, 2019).

Beyond these options, we are encouraged to see recent financial innovations working to address the decumulation challenge. A prime example is Purpose Investments’ launch in June 2021 of the Longevity Pension Fund – a mutual fund designed to accumulate funds to retirement, and then to convert the assets effectively into lifetime retirement income, including through the pooling of longevity risk. This product is available both to individual investors and to pension plans. We understand that other companies might be planning to launch similar products in the future.

Individual and Employer-Sponsored Life Income Funds

When a decumulation solution is not a feature of the employer-sponsored retirement program, participants may be referred to a third-party group LIF/RRIF. Third-party group LIF/RRIFs are generally offered by the recordkeeper – either a financial institution such as an insurance company or bank, or a non-financial institution that provides third-party administration services to the pension plan sponsor – of the accumulating asset program as a convenient option for terminating or retiring program members to transfer their assets on an individual basis.

These group solutions, or group rollover products, have been offered by recordkeepers for decades to terminated and retired CAP participants to enable them to transfer their assets from their employer-sponsored program to individual RRIF and LIF accounts within their group product. Many of these solutions have been improved over time to be more attractive to retiring participants by expanding the investment selections offered, reducing their fees relative to retail options available in the marketplace and, in some cases, providing advisor support and advice. Yet, based on our conversations with the country’s major insurers that provide recordkeeping services for these programs as well as on our own experience in administering these types of programs, the outflow of CAP assets to individual retail products, generally through banks, investment managers, brokerage accounts and financial advisors, appears to be the most popular action.

A CAP sponsor that would like to offer a decumulation solution to its members today may do so by offering its own employer-sponsored group LIF or RRIF as part of its retirement program. The decumulation program generally would provide access to the same administrative services, investments, decision support tools and fees that were enjoyed during the accumulation phase of the program.

Employer-sponsored decumulation solutions have several advantages over third-party group solutions or individual retail options:

- A trust and familiarity factor often exists between employees and their employer when it comes to the delivery of retirement programs. Endorsement from the plan sponsor for its sponsored decumulation feature can nudge members into making the right financial decisions.

- The program sponsor’s governance processes can scrutinize fees on a regular basis and keep them competitive. Members also can benefit from uninterrupted access to the program’s decision support tools and education channels, as well as to investments carefully selected by the employer and that the members trust.

- Often overlooked and, in our view, substantially undervalued is the benefit that asset retention and scale confer to the entire membership when an employer-sponsored decumulation solution is offered. Greater retention of assets increases the scale of an employer-sponsored program, leading to enhanced access to premium service, technology, industry innovation, institutional investor grade products and, importantly, ability to leverage that scale for lower fees.

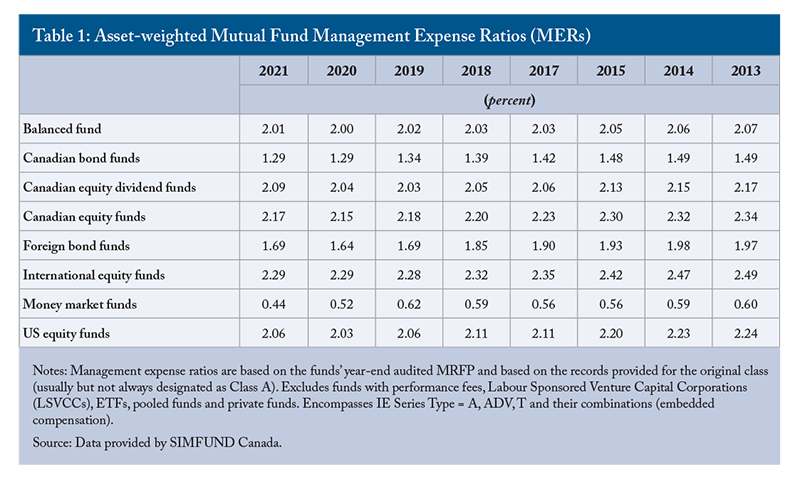

By retaining retirement assets within an employer sponsored plan that provides decumulation features, such as through an employer-sponsored LIF/RRIF or variable benefits provision in the case of DC pensions (explained in the next section), retirees can avoid the high retail investment fees that are common in Canada’s retail investment markets. According to data compiled by the Ontario Securities Commission and presented in Table 1, the asset-weighted Management Expense Ratio (MER) for balanced and equity mutual funds ranged from 2.01 percent to 2.29 percent in 2021, depending on the asset class and fund class. Some CAP retirees take advantage of group rollover programs for individuals offered by their group retirement program recordkeepers, which often offer lower fees than some retail options; based on our own research, these funds can be 20-40 percent lower than retail fees, in part due to the different advice and support model they offer.

More sophisticated investors and those with larger account balances can invest at lower fees, but these ranges are representative for the typical Canadian retiree. By contrast, assets that are retained within the employer-sponsored CAP, particularly a large one with assets of sufficient scale, are much lower than even those offered by group rollover programs. According to LifeWorks’ proprietary CAP Database, these fees for medium-large CAPs average between 0.50 percent and 0.75 percent for active management, or roughly half the fee levels offered by group rollover plans and potentially one-quarter the fees of retail products. Over a typical retirement, saving 1.5 percent per year in fees during the decumulation phase could afford the retiree an additional four to five years of retirement income.

For example, a 35-year-old CAP participant who contributes 12 percent (employee and employer combined) contributions per year over a 30-year accumulation period in a company-sponsored program and then decumulates through an individual LIF or RRIF to replace 60 percent of pre-retirement earnings – ignoring RRIF/LIF minimum and maximum limits for the sake of this example – and is paying investment fees on a retail basis of 2.0 percent per annum for a balanced fund in their retirement phase could be expected to deplete their assets at approximately age 86. If the same individual instead decumulates through the company’s Group LIF or RRIF, which charges only, say, 0.5 percent per annum for a balanced fund, the individuals’ retirement assets can be expected to generate an additional four or five years of withdrawals and ultimately to be depleted when the retiree is closer to age 90.

Although the lower investment fees achievable with scale of assets in a CAP (including Group LIFs and Group RRIFs) can improve retirement outcomes for participants, the benefit of an increasing scale of assets for the program as retired members’ assets are retained in the program will benefit all members, including new entrants, and enhance the competitiveness of the program. Yet, despite this, the addition of sponsored Group RRIF/Group LIF components does not address adequately the issue of longevity risk.

Variable Benefits Provisions in DC Pension Plans

Historically, and as discussed earlier, Canadian pension legislation required DC plan members to transfer their account balance out of their DC pension plan and into a LIF before they could begin drawing periodic retirement income. In recent years, amendments to pension legislation in Canadian jurisdictions, with the exception of New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador, have permitted variable benefits provisions within DC-registered pension plans. These legislative changes permit the sponsor of a DC registered pension plan to provide for the withdrawal of periodic retirement income from the plan itself. For a plan that provides for the payment of variable benefits, the rules regarding the payment of periodic retirement income mirror those that are applicable to former employees who transfer their account balance to a LIF.

Permitting variable benefits provisions in DC pension plans represents a major step forward. As previously discussed, a fundamental weakness of the Canadian retirement system is that, once their DC account balance is transferred to an individual vehicle, former employees might be left to their own devices to navigate the complexities and risks associated with managing their financial resources in retirement. Giving former employees the option of keeping their DC retirement assets in their former employer’s pension plan or withdrawing income from these funds during their retirement years enables them to continue to benefit from the advantages they enjoyed during the accumulation stage, including:

- governance of the pension plan by an administrator with a fiduciary duty to members of the plan;

- investment options selected and monitored by the pension plan administrator;

- fees that are typically lower than those paid by retail investors; and

- investment and personal financial education.

It is encouraging that several large DC plan sponsors have already adopted this model and are seeing good results. It likely represents the best currently available option for plan sponsors looking for an effective decumulation solution.

New Decumulation Vehicles

In 2021, the Canadian Income Tax Act and regulations were amended to permit two new vehicles: Variable Payment Life Annuities (VPLAs) and Advanced Life Deferred Annuities (ALDAs). If adopted in pension legislation and by the industry, these new vehicles could significantly enhance the options available.

Variable Payment Life Annuities

Although variable benefit provisions in DC plans provide former employees the advantages of being members of a DC pension plan during their retirement years, variable payment life annuities go further by pooling retired employees’ investment risk and, crucially, longevity risk with other retired employees who elect this option.

A VPLA fund within a DC pension plan converts the account balance of a retiring employee who elects this option into a monthly pension payable for the remainder of the retiree’s lifetime, based on assumptions about investment and mortality experience. The retiree’s monthly pension amount is variable in that it is adjusted periodically to reflect the actual mortality and investment experience of the pool of retired employees who elect the VPLA option. For example, if the rate of investment return of the VPLA fund is better (or worse) than had been assumed, the monthly pension of all VPLA retirees will be increased (or decreased). Similarly, if the overall actual mortality rates of the retired employees are higher (or lower) than had been assumed, monthly pensions of all VPLA retirees will be increased (or decreased).

The risk pooling of a VPLA bears some resemblance to an insurance product such as an annuity, but a VPLA does not provide the same level of guarantee as a life annuity purchased from an insurance company, since the monthly pension from a VPLA that a retiree receives is variable and can increase or decrease over time. Through the pooling of investment and longevity risk, however, a VPLA can greatly reduce the risk that a retired employee will run out of retirement savings.

In the absence of longevity pooling, individuals must make an impossible decision on how to allocate limited resources across a retirement of unknown length. Investment advisors typically recommend that people budget their retirement until an optimistic target of age 100, and some digital retirement planning tools use this same horizon. This advice is based on the premise that retirees fear outliving their assets, and would rather budget for a longer period than they are likely to need to avoid this outcome. It is, however, worth examining the implications.

The average life expectancy of the 65-year-old female retiree discussed above in the Longevity Risk section is 89½ and the probability of her living past age 100 is approximately 10 percent. This means that 90 percent of those following the advice to budget to age 100 will have unspent retirement assets at the end of their retirement. To quantify this effect, if the 65-year-old could reliably budget her savings to last until age 89½ rather than age 100, she could afford to increase her retirement spending by up to 23 percent (assuming a 5 percent per year rate of return and 2 percent inflation). Thus, a decumulation solution that includes effective longevity pooling, such as a VPLA, would allow retirees to save only for their expected lifespan, with those who die early effectively supporting those who live longer.

The quantification above focused on a single individual, but the same logic applies for a couple saving jointly for retirement; in any case, budgeting for the 10 percent event is a hugely inefficient use of retirement assets.

One could argue that effective allocation of assets to a person’s lifetime is not critical since assets remaining after a retiree’s death would be available to beneficiaries – in fact, some suggest that the fact that VPLAs typically do not leave assets for beneficiaries beyond a surviving spouse is a shortcoming (though the same could be said of most DB pension plans). This is true, but most individuals sacrifice consumption during their working years in order to save for retirement, and they lower their standards of living early in retirement to ensure that they do not outlive their assets. Although remaining assets at death might not truly be lost, they do fail to provide for the livelihood of the saver, as was their purpose. Given the choice, we expect that most individuals would choose to enjoy a higher quality of life during retirement without fear of outliving their assets. Individuals who are concerned about leaving excess assets as a legacy after their deaths and have the financial resources to do so, or who simply wish to retain more control of a portion of their assets, would have the option of allocating only a portion of their retirement savings to a VPLA, while the remaining assets could be managed differently, in order to leave excess assets after death.

The benefits of effective decumulation are generally expressed in terms of improving retirement income for a given amount of retirement savings. The corollary is equally true: a more efficient approach to converting retirement savings into retirement income means that a given level of retirement income could be achieved with substantially less retirement savings. In fact, if we acknowledge that, for most people, retirement savings come at the expense of current consumption, it follows that individuals could improve their current quality of life by saving less for retirement, assuming they were still saving enough to deliver an appropriate level of retirement income. This means that efficient decumulation would benefit not only an individual’s retirement years, but potentially their entire working lifetime by freeing up assets for consumption that would otherwise need to be saved for retirement. At the employer level, the same concept means that an employer could improve the financial well-being of the entire workforce through better use of resources in a vehicle that includes risk pooling, such as a VPLA.

Returning to our example of the 35-year-old participant, we had discussed that the reduction in fees afforded by an in-plan decumulation option could generate four or five additional years of retirement income. Viewed another way, the individual could generate the same level of retirement income for an annual contribution of 10 percent rather than 12 percent, or a savings of 2 percent of pay per year. If the individual was participating in a VPLA that provides longevity pooling in addition to fee savings, the same retirement income could be generated in exchange for an 8 percent per year contribution, or a savings of 4 percent of pay per year. This represents a one-third reduction in the cost of retirement.

A VPLA is also expected to provide a higher monthly pension – although at the cost of higher risks borne by pensioners – than a life annuity purchased from an insurance company for two reasons. First, life annuity pricing reflects the investment of premiums in fixed-income instruments in an attempt to “match” the expected monthly lifetime amounts payable to the retiree. The administrator of a VPLA fund may adopt a more diverse investment strategy that also includes investing a portion of the fund in riskier asset classes. This type of investment strategy is expected to increase VPLA monthly pension amounts if the strategy is successful in generating higher rates of investment return for the fund over time.

Second, a life annuity premium includes a charge by the insurer for guaranteeing the monthly lifetime pension amount and for the insurance company’s expenses and profit.

A few Canadian employers – most notably, the University of British Columbia faculty pension plan – have successfully provided VPLAs within their DC pension plans for decades. Since the late 1980s, however, the creation of new VPLAs has not been permitted under tax rules. Recent changes to the Income Tax Act regulations now permit the creation of new VPLAs within DC registered pension plans and Pooled Registered Pension Plans (PRPPs), but not for other types of CAPs such as Group RRSPs – although transfers in of assets accumulated in a Group RRSP might be feasible. Provincial and federal pension legislation will now need to be amended to permit this option, and progress on the required legislative changes is being made in jurisdictions such as Quebec and by the federal government.

While we look forward to these future amendments, we would like to see increased legislative and regulatory support for the aggregation of retirement assets – including those derived from employer-sponsored pension plans of any jurisdiction, personal RRSP assets, and so on, into a single VPLA, whether offered within a sponsor’s registered pension plan or in a PRPP. Permitting this would go a long way to improving the efficiency with which members can structure their retirement income and, in so doing, improve their retirement outcomes.

Some have argued that the longevity-pooling concept of VPLAs could also be extended beyond single-employer pension plans to stand-alone arrangements or pooled pension plans that do not require an employer-employee relationship. Conceptually, we agree with these suggestions, which could bring longevity-risk pooling to a larger audience. We believe, however, that these approaches might introduce additional risks and challenges to the model, and their assessment is beyond the scope of this Commentary.

Advanced Life Deferred Annuities

The Income Tax Act and regulations recently have been amended to permit insurance companies to offer advanced life deferred annuities (ALDAs).

Under previous tax rules, if individuals used their DC account (or any other type of registered savings account) to purchase a lifetime annuity from an insurance company, payment of the lifetime annuity was required to commence no later than the end of the year in which the individual turned age 71. An ALDA also provides a guaranteed lifetime annuity, but payment from the ALDA can begin as late as the end of the year the individual turns age 85. No more than 25 percent of the individual’s DC account balance can be used to purchase an ALDA. In addition, no more than $150,000 (indexed to inflation) in aggregate from all of an individual’s registered account balances can be used to purchase an ALDA.

Individuals might wish to use a portion of their accumulated retirement savings to purchase an ALDA, thereby protecting themselves against the risk of running out of retirement income when older. Since an ALDA allows the annuity to start as late as the end of the year in which age 85 is reached, the expected annual payout from an ALDA is much greater than that of an immediate annuity, per dollar of premium paid. This enables individuals to manage the remainder of their DC savings in a vehicle such as a LIF to finance their retirement (and provide retirement-income flexibility) during the period leading up to the commencement of their ALDA, knowing that they will not run out of retirement income if they live to a very old age.

Although ALDAs could be very beneficial from a financial well-being perspective, it is not yet known how many insurers will offer this product or how attractive their pricing will be. In theory, DC members looking to manage longevity risk should perceive an ALDA as an attractive option, but there is a healthy amount of skepticism in the industry that serious demand for them will arise. Given the lackluster demand for similar products available in the United States and Australia, for example, and given the weak demand in Canada for regular life annuities, we are inclined to agree. Employers will need to educate their DC plan members about the benefits of ALDAs, and other strategies to mitigate longevity risk, as it is unlikely that the benefits of these solutions will be obvious to most pension plan members without concerted educational effort.

The Way Forward

As discussed, one of the main differentiators between large DB plans and most of today’s CAPs is their ability seamlessly to provide lifetime retirement income and ideally to pool longevity risk. The adoption of decumulation features inspired by the DB world within CAPs, with or without longevity-pooling features, can have a substantial impact on this shortcoming. These programs can and should deliver lifetime pensions and not just accumulated assets for plan members. We see their ability to do so as a critical and anchoring component of a financial wellness program and indeed for a workforce’s total well-being.

CAP Sponsors Must Lead the Way

Many employers already sponsor DC plans for their employees, in which case they already have the infrastructure in place to add features such as variable benefits and VPLAs in an efficient and cost-effective manner. Most employees trust their employer and are already familiar with their DC plan, which will likely will make the adoption of expanded DC plan features more successful. Employers are also well positioned to advocate for innovation from service providers and for legislative changes that enhance the decumulation landscape in Canada.

The acceptance of in-house decumulation solutions among plan sponsors, however, has been somewhat slower than hoped, as the vast majority of CAPs do not yet offer these options: based on our experience in this area, less than 5 percent of programs administered by the largest insurance companies in Canada offered decumulation options in 2021. Instead, most CAP sponsors have delegated to their recordkeepers or advisors the role of providing information about the options available to members who are approaching retirement, as well as any actions they must take and within what period, and any default option that may be applied if no action is taken. Some CAP sponsors have gone further and have engaged their third-party providers to host pre-retirement education sessions targeted to members ages 55 and older and to initiate outbound calls to pre-retirees. More recently, they have endorsed the service providers’ financial advice network to provide one-on-one counselling to retiring members about how, when and where to decumulate their assets. All these activities that serve to better equip and prepare members to make sound decisions are welcomed and should be encouraged. But these activities do not come without the responsibility of the plan sponsor to monitor them, particularly if, as most often happens, the third-party recordkeeper or advisor is offering proprietary products to accept these asset transfers.

Conflict of interest in these circumstances, whether real or perceived, is a challenge. Although recordkeepers and regulators often take steps, including audits, to manage this risk, plan sponsors should remain diligent in their governance processes and the monitoring of their service providers to ensure that support provided is impartial and balanced and that any conflicts of interest are disclosed transparently.

There is much debate within the industry and among plan sponsors about the perceived additional administrative burden, cost and risks for employers in offering decumulation features to plan participants. The materiality of any such costs generally will depend on the characteristics of the program and its population. In fact, greater overall scale can often generate significant savings in overall investment management fees that benefit not just retiring members but the entire membership.

Added administrative burdens can also be mitigated. The same frameworks that plan sponsors have put in place to govern their CAPs during accumulation are leverageable and extendable to the decumulation phase. And CAP recordkeepers are well equipped to keep track of retirees – in fact, they do already when terminated and retired members exit employer-sponsored programs for third-party product offerings. Scale is certainly an important factor influencing employers’ adoption of some decumulation solutions. VPLAs, for example, might best be considered by DC plan sponsors with assets and membership of a certain size to be practical. Product innovations, including an innovative mutual-fund-based model, are also arriving in the marketplace that would be accessible and implementable to plans of all sizes – and we expect these innovations to continue. However, even smaller CAPs could benefit from introducing the simpler decumulation features described above, and in time we would expect additional options for pooling longevity risk across smaller plans to be tested.

Many have argued that a plan sponsor’s fiduciary risk ends, or is effectively transferred to the third-party provider, when retiring members transfer their assets out of the plan sponsor’s program. Chief Justice McLachlin stated this about fiduciary risk: “The essence of a fiduciary relationship is that one party exercises power on behalf of another and pledges himself or herself to act in the best interests of the other.” There is room to consider that the introduction of program features intended to produce better retirement outcomes for participants is an action that is indeed in the best interest of members. An improvement in outcomes for all could conceivably even reduce the risk of challenge from program participants whose retirement assets might otherwise fail to support their lifestyle spending in retirement. Many sponsors who have already implemented decumulation features or are looking to do so in the short term have argued that ignoring the benefits of decumulation might pose a greater fiduciary risk when they could have taken actions to improve outcomes for their plan membership but failed to do so.

Against these potential added burdens are benefits that employers could enjoy by providing effective decumulation features to plan members as they transition to retirement:

- Plans with decumulation features are more likely to be seen as true pension programs, rather than mere accumulation vehicles, and are becoming more critical for employers seeking to attract and retain the talent their businesses need. Paternalism might be outdated, but evidence shows that caring employers who prioritize the total well-being, including financial well-being, of their people attract a higher-quality workforce. Offering retirement support not only serves to reduce employee stress; it also helps them to be more productive and to feel valued by the employer. Improved transparency and options around decumulation can improve employee performance by mitigating the impact of a broad category of soft risks, such as employee disengagement and dissatisfaction, distraction and inadequate productivity, the inability or unwillingness of employees to retire and reputational risk.

- CAPs generally are thought of as deferred employee compensation and as an expense to the employer. However, it is not the contribution that the employee should value but rather the outcomes to be derived. To the extent that employers are able to provide a similar level of retirement income to their retirees at lower costs, they – and their employees – could end up making smaller contributions to the program.

Fundamentally, we believe that the good that comes, to both employer and employees, from offering employer-sponsored decumulation features and support for participants far outweighs the challenges, which can be managed. Regardless of which side of the argument one might fall on, it is important to have considered the issue carefully, engaging with consultants or impartial advisors as needed to contemplate all the pros and cons and to make a decision that can be supported, documented and revisited as the market continues to evolve.

Supportive Legislation and Regulatory Policies Should Be Implemented

Pension policymakers and regulators also have an important role to play. Legislation and regulatory policies should support innovation and practical solutions in the decumulation space.

The structuring of retirement income for a lifetime from multiple sources of government and public/private sector retirement programs of different types, in combination with personal retirement savings from RRSPs, TFSAs and non-registered assets, is more complicated than it needs to be for retirees and as a consequence poses an impediment to efficient and optimized retirement outcomes.

We recommend that policymakers and regulators take the following five actions to improve and simplify access to effective decumulation strategies and improve retirement outcomes for Canadians:

- Regulatory harmonization of locking-in/unlocking rules across jurisdictions to allow a single set of rules to apply to DC assets during retirement, irrespective of the jurisdiction under which the accumulation took place.

- Regulatory harmonization of rules concerning variable benefit payment, variable payment lifetime annuity and LIF maximum withdrawals, irrespective of the jurisdiction in which the assets accumulated.

- Legislative and regulatory support for pooled decumulation vehicles that permit transfers in of retirement assets, including those derived from employer-sponsored pension plans, personal RRSPs and so on.

- Specific decumulation guidelines for program sponsors to provide support for the adoption of decumulation frameworks.

- Support and guidance for the provision of decumulation specific retirement advice for retiring members.

Support Tools and Members’ Education Should Be Strengthened

The availability of good decumulation options, supported by robust and easy-to-use decision-support tools, is critical to improving retirement outcomes. In addition, the education of CAP members about the importance of decumulation and the pros and cons of various solutions is a key component that should not be forgotten. Retirement issues and Canada’s retirement system are complex, and it cannot be assumed that, without the appropriate education, DC plan members will understand the value of solutions such as variable benefits, VPLAs and ALDAs. To maximize the effect of current and future decumulation options, a strategy of frequent, clear and unbiased members’ education is needed. Governments and service providers have a role to play here, but we would argue that sponsors of employer plans are best positioned to offer such information.

Conclusion

Employer-sponsored decumulation features have a significant role to play in the quest to achieve the financial well-being, not just of retiring members, but for the entire membership of the plan. With the knowledge and improved confidence about the pension they will receive, and expected support throughout their post-retirement journey, active employees also benefit from decumulation features.

With so much to be gained by DC plan members, sponsors and Canadian society in general from the transition of such plans from purely accumulation vehicles into true pension plans, all stakeholders in Canada’s retirement system (and especially plan sponsors and legislators) should grasp the opportunity that is before us to enhance our retirement system and improve the financial and total well-being of Canadians during both their working years and in retirement.

We acknowledge gratefully the financial support of Dean Jane Philpott of Queen’s University’s Faculty of Health Sciences, and of the assistance of her advisory group of Catherine Donnelly, School of Rehabilitation Therapy, John Almost and Joan Tranmer, School of Nursing, and from St. Lawrence College Barbara LeBlanc, Dean of Health and Wellness and Barry Weese, Associate Dean of Allied Health. We are grateful for material and comments received from Rosalie Wyonch of C.D. Howe, support from Parisa Mahboubi and comments from internal and external reviewers organized by the C.D. Howe Institute.

References

MacDonald, B.-J., B. Sanders, L. Strachan, and M. Frazer. 2021. Affordable Lifetime Pension Income for a Better Tomorrow: How We Can Address the $1.5 Trillion Decumulation Disconnect in the Canadian Retirement Income System with Dynamic Pension Pools. Toronto: National Institute on Ageing, Ryerson University and Global Risk Institute.

Statistics Canada. 2020a. “Life expectancy (LE) and health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) in years at ages 25 and 65 by education categories and income quintiles, by sex, household population, Canada, 2011 with five-year mortality follow-up.” Online at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2020001/article/00001/tbl/tbl01-eng.htm

______. 2020b. “Percentage of paid workers covered by a registered pension plan.” Tables 11-10-0133-01 and 14-10-0027-01. Ottawa. Online at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200813/t002b-eng.htm

______. 2022. “Registered Pension Plans (RPPs), active members and market value of assets by contributory status.” Table 11-10-0106-01. Ottawa. Online at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110010601