Study in Brief

- The current spending review underway in Ottawa is a modest start and should be followed by more comprehensive, regular strategic reviews of spending and programs drawing from past Canadian and international experience.

- In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, a burgeoning deficit and new expenditures, and the rapidly changing economic and security climate, the launching of a comprehensive and systematic review is well overdue. Ottawa should not only launch a comprehensive review, but also institutionalize annual reviews and expand the capabilities of the public service to carry them out.

- The authors explain the arguments and pressures for implementing annual spending and/or strategic reviews, including prudent fiscal policy, prudent public management, driving innovation, and meeting public expectations. They consider the Canadian and international experience with different kinds of spending or strategic reviews. Lastly, they identify the pre-conditions and design considerations for regularized spending or strategic reviews and recommend practical steps a government might take to prepare for institutionalizing reviews.

The authors thank Alexandre Laurin, Benjamin Dachis, Don Drummond, John Lester, and Peter Wallace for helpful comments on an earlier draft. The authors retain responsibility for any errors and the views expressed. The authors also wish to thank their dedicated research assistants on this important project: Gita Zareikar, Keita Hashimoto, Irene Huse, Hayat Askar and Jacky Tweedie.

Introduction

In the February 2022 federal budget, the government of Canada announced a spending review consisting of a “strategic” review of skills training and youth programs, requiring departments and agencies to identify reductions in planned spending. This was the first time in many years that a government had launched an expenditure review. The initiative was confirmed in the February 2023 budget alongside a multi-year savings target of $15.4 billion (Curry 2023a), with proposals submitted and decisions made in fall 2023 to be factored into the spring 2024 budget. There have been notable differences in reaction to the announcement. Opposition Leader Pierre Poilievre promised that, if elected, any new spending under his government would require off-setting cuts; Jagmeet Singh pointed to over-spending on consultants (Curry 2023b); and a well-known former government official argued that anything less than cuts from actual – as opposed to planned – spending was “bogus,” because the projected savings base has been obfuscated (Drummond 2023; Curry 2023b).

We argue that – in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, a burgeoning deficit and new expenditures, and the rapidly changing economic and security climate – the launching of a comprehensive and systematic review is well overdue. Nevertheless, a federal spending review has been launched. This is a modest start. The time is ripe for Ottawa not only to launch a comprehensive review animated by targets, but also to institutionalize annual reviews and expand the capabilities of the public service to carry them out. We recognize that fiscal pressures will continue to mount, that priorities of governments will evolve, and that objectives will shape the character of review-processes. However, successive governments have shown disinterest in establishing regular spending or strategic review exercises. For this reason, it is important to facilitate institutionalization by building capacity and honing the design to allow for flexibility in focus and scale.

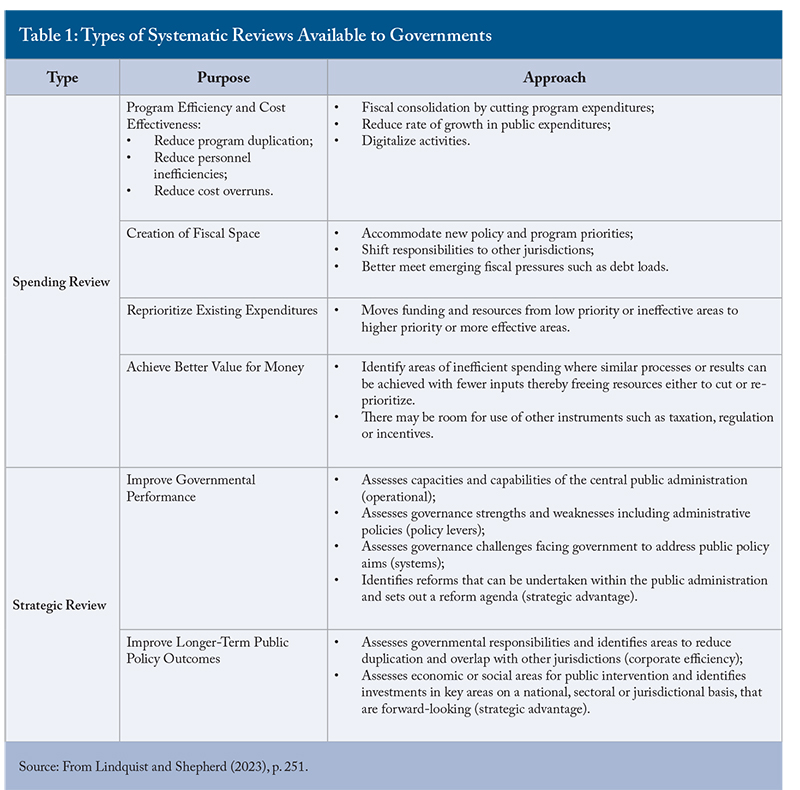

Table 1 shows a continuum of possible objectives associated with spending reviews of the government’s annual budget. Spending reviews enable governments to manage aggregate expenditure levels by identifying savings or reallocation measures within existing programs or policy envelopes. Conversely, strategic reviews attempt to find new value-creating opportunities that maximize governmental success over the longer term. It is possible to see these as separate categories of reviews or as a continuum (Tryggvadottir 2022). It is also important to understand that a review process could comprise a combination of review exercises.

The irony is that the government of Canada has had noteworthy experience with different kinds of spending or strategic reviews going back to the Mulroney, Chretien and Harper governments. Most notable was the 1994-96 Program Review of the Chretien Liberal government, widely held up as an international exemplar by the OECD (Bourgon 2009; Tellier 2022). However, these reviews have only been launched episodically with each being quite different, including those of the Harper and Trudeau governments which opted for variations on closed processes (Shepherd 2018; Lindquist and Shepherd 2023). The spending reviews of Denmark and the Netherlands are now seen as international exemplars: they proceed annually, they can be scaled up and down as needed, they rely on external experts as well as public servants, and the analysis and conclusions are more public. These examples, along with others we share in this Commentary, show how spending or strategic reviews can be more open and forward-looking, and could work across levels of government, supported by standing review of capabilities, methods, and repertoires. Such examples point to important design principles and are worthy of emulation. The purpose of this paper is to identify a potential strategy for the government of Canada to begin developing such this approach.

What follows has four sections. The first section reviews the arguments and pressures for implementing annual spending and/or strategic reviews. The second considers the Canadian and international experience with different kinds of spending or strategic reviews. The third section identifies the pre-conditions and design considerations for regularized spending or strategic reviews. Finally, we offer recommendations on practical steps a government might take to prepare for institutionalizing reviews.

The Case for Annual Spending Reviews

When calling for spending reviews, politicians and commentators typically have different motivations in mind. These are important to recognize as they determine how reviews should be designed, the capabilities required to undertake them, the criteria and information needed to inform them and, ultimately, what constitutes success. There are six distinct reasons for undertaking strategic or spending reviews in government:

- Prudent fiscal policy. There is a prevalent concern among politicians and commentators about the overall trajectory of public spending, and the need for fiscal sustainability. The focus here is on fiscal aggregates and ratios, such as the relative size of the deficit, the amount of public debt, the debt-to-GDP ratios, and interest-cost/ revenue ratio. Although views differ on overall levels of taxation, there is agreement on the need to keep deficits and debt under control, perhaps with instituting expenditure limits. This concern is, in part, motivated by Canada’s precarious fiscal position in the early 1990s, when debt interest payments consumed 30 percent of federal government outlays. The motivation here, then, is to keep deficits under control and, if spending and deficits exceed acceptable limits, then the reflex is to use spending reviews to reduce spending and possibly cut programs – hence the interest in “cuts exercises.”

- Prudent public management. Government policies and programs are often launched with ambitious goals and good intentions, but a fundamental principle of good government and public administration is to ascertain whether they live up to expectations. The motivation is to ensure good value for taxpayers’ contributions. Several well-known methods are employed to this end: evaluations, internal and external audits, and performance reporting and monitoring. However, these initiatives often proceed independently and are closely held by officials, thus failing to cohere in the service of strategically reviewing policies and programs. If designed appropriately, reviews can draw together multiple lines of evidence on the performance of policies and programs, enabling adjustment as needed.

- Generative learning. The prudent management argument presumes that government policies and programs are instituted and implemented in relatively stable contexts. But what happens when a shock occurs and governments must move quickly to improvise a response to crises? The most recent example of this was Canada’s experience with the COVID-19 pandemic, when huge outlays were made for rapidly designed programs to assist individuals and business. One can, however, imagine other kinds of rapid and wholesale changes to the national economy or international environment. There is a need for taking stock, assessing, and learning from what has transpired, not only to determine what worked and whether responses could be improved, but also to determine where policies, programs, and the needs of citizens stand. The guiding questions might be: should governments revert policies and programs to their pre-shock state, or should they be re-thought given new information? Such retrospectives are often needed when a single policy sector experiences a significant shock, but the argument is all the more pressing with a broad shock such as the COVID-19 pandemic which affected many sectors.

- Driving innovation. This perspective is motivated by the ongoing stream of innovation from the private sector and best practice from other governments on how to design better public policies and deliver programs. There are always advocates for ways to “reinvent government” with new technologies, management frameworks, and best practices for the delivery of public services, seeking a path to efficient or effective government. The argument for designing reviews with innovation in mind is that traditional reviews informed by audit, evaluation, and performance management regimes tend to be focused on appraising how well policies and programs worked as designed and implemented, and do not consider whether they could be delivered in different ways. While progressive evaluation designs have considered ways to improve and better drive the achievement of results and policy aims.

- Anticipatory policies. Rooted in the understanding that policies and programs reflect the context and assumptions of governments and societies when they were designed, this perspective asks what happens when domestic and international contexts evolve precipitously, perhaps due to technological, geopolitical, or climate shifts? Reviews can be necessary when there are rapid and seemingly irreversible shifts in governance environments, requiring the adoption of new priorities, and preparing for very different realities in every policy sector. Strategic reviews can raise questions about where – looking five or ten years into the future – a government might want to “skate to” in policy sectors, and whether it is prudent to continue relying on policies and programs designed for a different era. A spending review would assist by offering advice on where expenditure efficiencies can be made that align with future priorities.

- Meeting public expectations. Many of the above arguments can be viewed as managerial or technocratic in nature, differing only in the objectives they prioritize. However, there are also political arguments in favour of reviews. Since the early 1990s, citizens, business and civil society groups have prized the keeping of the national deficit and debt under control (i.e., a debt level that does not impede adequacy of program spending), rewarding governments that have launched spending review initiatives (i.e., the Chretien government after the 1994-96 Program Review and the Harper government after its reviews in response to the Global Financial Crisis) (Lindquist and Shepherd 2023; Lindquist 2022; Shepherd 2018). In short, working to motivate fiscal prudence makes for good politics. Whether such reviews are focused on – and deliver – cuts or involve reallocations towards new initiatives is an open question. But, at the very least, governments can use spending reviews to signal interest in prudent fiscal policy and the management of programs.

All these arguments differ in focus,

There are incentives, of course, for governments to maintain the status quo without spending or strategic reviews. The first is that cuts and expenditure reduction exercises, a possible outcome of these reviews, will likely offend affected stakeholder groups who have vested interests in retaining programs or services. A second argument is that undertaking a review – especially more thorough and comprehensive strategic reviews – requires already scarce ministerial time and may not be consistent with the overall communications priorities of the government. Third, if a government and its public service are unfamiliar with undertaking reviews, they will not have developed the requisite capacities and repertoires and establishing them may seem quite daunting. Fourth, beyond the simple “cuts” exercises, lead times for reviews will be longer and the resulting decisions and announcements, often taken months and sometimes years later, may come at an awkward time in the political cycle. This means the shorter-term future carries some political risk, while the benefits of the review would only be realized in the longer term. Finally, governments and central agencies may opt for the quieter path of least effort: requiring departments and agencies to find and liberate resources from existing or planned budgets, betting on possible upturns in the government’s revenue situation that might lessen the need to make difficult decisions.

These disincentives to launching reviews, along with the prevailing review style of the government of Canada, can be seen as forms of “grooved thinking,” and advocates for institutionalized reviews need to focus on overcoming them (Nelson and Winter 1985). The next section takes a closer look at the Canadian style for spending or strategic reviews and compares it to the practice of several other jurisdictions.

The Canadian and International Experience with Spending Reviews

From the early 1980s, different Canadian governments (Mulroney, Chretien, Harper, Trudeau) carried out episodic spending reviews, varying considerably in their breadth, objective, and degree of openness. The Chretien Program Review (1994-1996) was hailed as a success and considered an international exemplar. Since then, though, the Canadian approach to spending reviews has become more attenuated. Other countries – the Netherlands, Denmark, Ireland, and Spain – are currently held up, ahead of Canada, as international models for spending reviews. What follows draws on Lindquist and Shepherd (2023), and more recent research, to juxtapose the Canadian experience with spending reviews against the approaches of these other jurisdictions. The earlier Canadian experience with spending reviews, along with the more recent international experience of these other jurisdictions, provides us with a sense of alternative, feasible possibilities in developing a more robust approach to reviews in Canada.

The Government of Canada’s Experience with Spending and Strategic Reviews

With respect to public budgeting, Canada has been known internationally for the 1994-1996 Program Review. That was, however, almost 30 years ago. Subsequently, the Harper and Trudeau governments carried out spending reviews that were less elaborate and more closed in their design, jealously guarding executive control. Often forgotten is the 1984-1986 Task Force on Program Review under the Mulroney government. This was considerably more transparent, open and independent than the more recent reviews.

The Mulroney Government Review. The Task Force on Program Review (NTFPR) was announced by Prime Minister Mulroney the day after his party won the 1984 federal election. It was a comprehensive review of almost a thousand programs delivered by the government. The task force committee was composed of the prime minister’s most senior ministers – the deputy prime minister, the minister of finance, the minister of justice, and the Treasury Board president. Over 200 private- and public-sector experts were invited to form an external advisory council, to review reports from over 20 departmental study teams. The last of the study team reports was received in December 1985 and tabled, along with a final overview report, by the deputy prime minister in March 1986 (Wilson 1988). The result was underwhelming. Aside from taking many months to complete, which allowed the recommendations to be pushed aside by other political priorities, it was not clear if the study teams were to identify cuts and efficiencies, encourage better management, identify alternative models for delivering programs, or eliminate programs. The work of the NTFPR was hindered by its openness and over-shadowed by announcements in the November 1984 mini-budget and the 1985 budget; in short, the ideals of the review process became disconnected from the realities of governing. While significant policy decisions did not emerge from the NTPFR, the government did announce selective changes, across-the-board spending restraints, regulatory reform, and a new bureau for real property management (Wilson 1988). This proved disappointing to many participants and observers hoping for greater shifts in government policies and programs.

The Chrétien Government Review. The Program Review was launched in 1994 immediately after the first budget. The nation’s finances were in serious difficulty, debt-servicing consumed roughly 30 percent of government outlays, and further possible credit agency downgrades were looming that would increase debt-servicing costs, lead to across-the-board expenditure cutbacks, and stifle growth. Finance Minister Paul Martin undertook extensive consultations before the first budget, in February, with provincial governments, experts, and the public, building consensus on the need to control public finances (Lindquist 1994). The Program Review was formally announced in-mid May 1994 along with a small secretariat in the Privy Council Office. Initial briefings were sent to ministers and their departments in June, and more detailed guidelines were shared in July to guide the strategic action plans that were to be submitted by August 31. All of this was driving towards the February 1995 Budget. In mid-September, a steering committee of the most experienced deputy ministers, chaired by the Secretary to Cabinet and the head of the Public Service, started to review the draft plans. A special cabinet committee of nine senior ministers vetted the proposals and built consensus, finally sharing the results with the full cabinet to ensure a balanced package and united front to the Liberal caucus, and to the public. A cabinet retreat was held in October to review the proposals and approve highly differentiated program decisions and spending targets for departments. The final package was tabled at another cabinet retreat in mid-January 1995 and the decisions were announced in the February 1995 Budget (for details, see Paquet and Shepherd 1996; Bourgon 2009; Tellier 2022; Lindquist and Shepherd 2023).

Despite the difficult decisions that were made, the Program Review process was eventually lauded, because the federal deficit was eliminated by the 1997-98 fiscal year, and 11 years of surpluses with a smaller public service followed (Bourgon 2009). Another round of review, focusing on horizontal issues, took place during 1995 and was reflected in the 1996 Budget. These decisions, along with the June 1993 restructuring of the Public Service, added to considerable dislocation across the Public Service. Because the ultimate decisions could not be incremental (which would have effectively meant returning to the series of across-the-board cutbacks announced by the Mulroney government), the review committee felt empowered to take a hard look at whether the federal government should be involved in delivering some programs at all. It determined which programs were to be preserved, and it considered new ways to deliver and finance programs, reducing overall spending. Many gaps surfaced in different policy and service delivery sectors, some quite significant, such as the loss of funding for affordable housing and supports for the homeless (Tellier 2022). The goal was deficit and debt reduction, not by means of across-the-board cuts, but rather by identifying which programs could be eliminated or delivered differently (Bourgon 2009). In short, the Program Review was both a targeted spending review, with departments and particular programs experiencing different levels of cuts, and a series of strategic reviews with surviving programs aligning with new governmental priorities and responsibilities in several sectors.

The Harper Government Reviews. Prime Minister Harper’s government was elected in February 2006 on promises of tax cuts and increasing the cost-effectiveness of government. Two rounds of review were undertaken under the government: the 2007-2010 “strategic reviews,” and the 2011-2015 “strategic and operating review” (Curran 2016). Although they had different aims and approaches, they both focused on cutting costs, were comprehensive in scope, and were coordinated by a unit in the Treasury Board Secretariat (Shepherd 2018). Details about the process and nature of the reviews were tightly held as the government relied heavily on consulting firms (Wells 2011; IFSD 2017). The strategic reviews flowing from Budget 2007 sought savings of $2.8 billion for that year, requiring departments and agencies to assess all direct program spending according to tests similar to those in the Program Review, including the operational costs of statutory programs on a four-year cycle and contributions to third-party delivery (Shepherd 2018).

In 2011, the Harper government expanded and renamed the strategic reviews as the Strategic and Operating Review (SOR). Originally envisioned as a one-year effort to find efficiencies in the public service (including assessments of salaries, benefits, and outsourcing), it focused attention on $80 billion of direct program spending, seeking a minimum of $4 billion in ongoing savings for the 2014/15 fiscal year (Canada 2011). The SOR homed in on finding efficiencies in administrative functions and eliminating non-essential functions. It was neither a strategic policy nor administrative review; it instead sought savings to balance the budget in the wake of the infusion of infrastructure funding from the Economic Action Plan (Lindquist 2022). By 2015, the combination of regimes had placed Canada in a position to weather the effects of the global financial crisis, as evidenced by a steady debt-GDP ratio of 30 percent.

The Trudeau Government Review. The Trudeau government was first elected in October 2015, but its first “spending” review was announced in the February 2022 Budget, well into its third mandate. The government was preoccupied in its second mandate with the COVID-19 pandemic, which after spring 2020 led to unprecedented spending to deal with public health, economic, and social pressures. Between 2019 and 2022, the federal net debt to GDP ratio increased from 29.8 percent to 47.5 percent (PBO 2022). In its 2021 Economic and Fiscal Update the government announced it would begin efforts to balance its budget by 2026-27 targeting a deficit of .04 percent of GDP, and a net debt to GDP ratio of 44 percent. Budget 2023 announced the introduction of “cross-government program effectiveness” (i.e., across government departments and agencies) reviews, to be led by the President of the Treasury Board (Canada 2023). Reviews were to be carried out in phases, with the first phase focused on skills training and youth programs, as well as a series of targeted cuts.

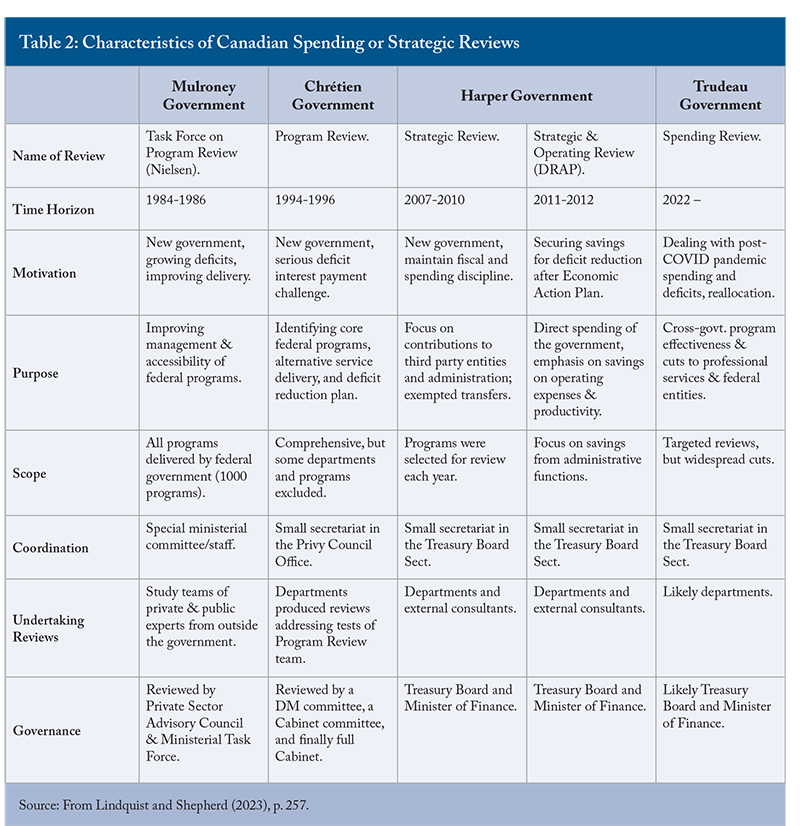

Canadian spending review patterns. Table 2 provides a summary of all the reviews across four governments. Canada’s approach to spending and strategic reviews has varied since the 1980s, but they have been episodic across all governments, mostly launched early in the mandates of newly elected governments (Mulroney, Chretien, Harper), with the Trudeau government as the exception. Over the last decade both the Harper and Trudeau governments settled into a closed, tightly held approach to spending or expenditure reviews, usually focused on securing savings, but often selectively exploring alternative policy and service delivery options (see Table 2). Since the Nielsen Task Force, the reviews have not involved external experts from other sectors or levels of government: they have been unilateral, federally focused, and closely held (Lindquist 1996). The Nielsen Task Force stands alone as the only review which publicly shared reports from the study teams. Finally, apart from the Chretien government’s Program Review, there has been relatively little public engagement in advance of, or during, the reviews.

International Exemplars for Spending Reviews

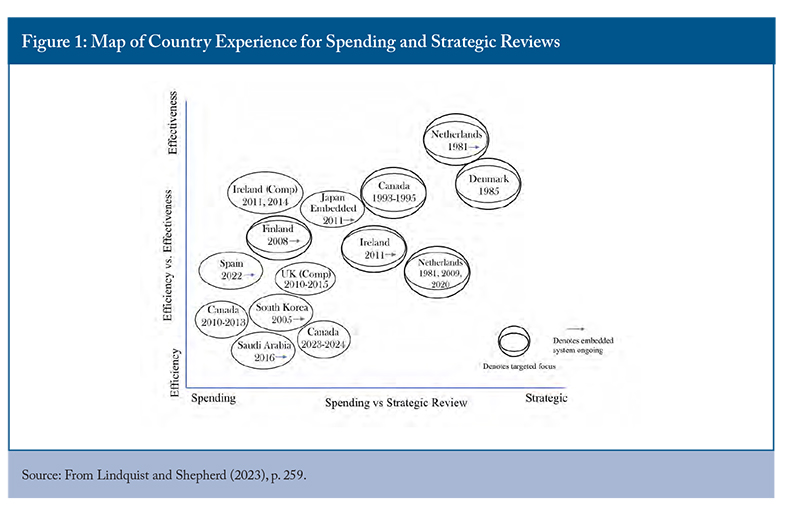

Over the years, the OECD has provided a forum for the exchange of budgetary practice and, more recently, has focused on spending reviews. The OECD has undertaken a recent study on spending reviews based on a survey of different governments, identifying how regular and selective or comprehensive their reviews are (Tryggvadotir 2022). Figure 1 shows that many jurisdictions carry out spending reviews episodically. This is usually in response to significant fiscal challenges such as the deficits of the 1980s, the Global Financial Crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, or perhaps following the election of a new government with different fiscal and expenditure priorities. Several large jurisdictions – the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Canada – have relied on episodic comprehensive reviews, which require considerable effort and strong backing from the elected government of the day.

We supplemented and updated this work with additional research into public documents and the academic literature. What follows focuses first on Denmark and the Netherlands, which the OECD showcases as international exemplars. We then discuss Ireland and Spain where the governments undertake regular, but not annual, comprehensive spending reviews to varying degrees. Finally, we consider two other jurisdictions, Japan and South Korea, with more robust and embedded budget and performance management systems, where reviews are implemented under these broader frameworks.

The Dutch Experience. The government of the Netherlands has commissioned annual spending reviews since the early 1980s, but these have varied in number and focus, and have covered programs delivered by one or more departments. The cabinet decides on the topic areas with reference to government priorities. The steering group (a commission) consists of senior civil servants, chaired by the Director-General of the Budget. The working groups undertaking each review are led by a prominent expert and include senior representatives from relevant line ministries, the Ministry of Finance, and external experts. Each is supported by an independent secretariat of two Finance and two ministry officials and can propose options not aligned with government policy (Doherty and Sayegh 2022; De Witte and de Jager

2020; Tryggvadottir 2022; Zielinski, Tryggvadottir and Lau 2021). The reviews are coordinated by a dedicated Bureau of Strategic Analysis, located in the Ministry of Finance’s Budget Directorate. They are designed to link closely with the annual budgetary cycle (Tryggvadottir 2022). After a budget, selective reviews, accompanied by targets, are often announced on policy areas believed to require fiscal discipline, or analysis for better ways to spend. These can arise from a combination of budgetary coalition agreements and negotiations (Government of the Netherlands 2021; Robinson 2022; Van Nispen 2016). However, as happened after the Global Financial Crisis, reviews can be scaled-up to a fully comprehensive review (De Witte and de Jager 2020). The Terms of Reference, once approved by cabinet, are made public. Each working group’s report and recommendations are defended before cabinet and published, along with the cabinet response (DeWitte and de Jager 2020). Under this process, cabinet is clear that internal review decisions are not simply to be accepted but undergo close scrutiny reminiscent of the Canadian 1995 Program Review process.

The Danish Experience. The Danish government instituted a spending-review regime in the 1980s which continues to this day. Topics for special studies are identified by the minister of finance and then approved by the Cabinet Economic Coordination Committee each February, as part of preparations for the next budget. The reviews are calibrated to focus on policies or programs administered by a department, or on horizontal programs spanning multiple departments, with a view to increase efficiency and effectiveness, and reallocate to higher priorities. Targeted internal ministry or sectoral reviews may be vertical, in which all or part of the spending of one government ministry or agency is reviewed, or horizontal, in which a particular category of spending or policy objective is assessed across the entire government. For example, climate-related spending or ICT (information and communications technology) acquisition and management require horizontal review. The working groups for each review comprise officials from the Ministry of Finance, pertinent departments, and outside experts, with either the Ministry of Finance or a lead department taking responsibility for coordination. Over the years these reviews have focused on cutbacks, but some are initiated voluntarily as a way of ensuring ministry spending aligns continuously with cabinet priorities. Such reviews are continuous and ongoing, with working groups submitting final reports each June to assist deliberations that inform the next budget (IMF 2019, 2022).

The Irish Experience. The Global Financial Crisis revealed weaknesses in Ireland’s fiscal policy and budgetary institutions, leading to a comprehensive spending review in 2009 and reform of approaches to budgeting and reviews (Robinson 2014; Boyle and Mulreany 2015; Kennedy and Howlin 2017; Tryggvadotir 2022). The Irish government has since initiated regular, but not necessarily annual, comprehensive reviews involving line ministries, external experts, and the publication of review reports after budgets. Led by its newly elected coalition government in 2011, the first review came in response to very difficult fiscal challenges. The Special Group on Public Service Numbers and Expenditure Programs sought to reduce program expenditures and the size of the civil service. They were conducted by line ministries led by five external expert groups from the private and public sectors which provided recommendations to the Ministry of Finance (Postula 2014; Government of Ireland 2009). In 2011, the government established the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (DPER) to coordinate spending reviews and integrate them into the annual budget (DPER 2023). In 2012, the Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service (IGEES) was created. It is a cross-government service of economists and policy analysts to support DPER, now providing over 200 analysts to DPER and line departments (Government of Ireland 2020; Ruane 2021). A second review, the Comprehensive Expenditure Report (2012-2014), arose from Ireland’s entry into the EU/IMF Program in 2011, and looked at all areas of spending with the aim of meeting fiscal targets (PBO 2019). Successive spending reviews have since been launched (2015-2017, 2017-2019) that have been focused on government re-prioritizations, along with assessments of efficiencies and effectiveness (Tryggvadottir 2022; PBO 2019). 2022 saw the launching of six review clusters, encompassing 26 individual spending reviews in 12 departments, mostly focused on specific policies (e.g., “Review of the COVID-19 Online Retail Scheme”) but also on sectors (e.g., “The Irish Government’s Expenditure on Children in 2019”). (Government of Ireland 2023ab; Tryggvadotir 2022; PBO 2019).

The Spanish Experience. Spain’s federal Council of Ministers recently initiated strategic program reviews that involved its highly devolved national, regional, and municipal governments (Escriva 2022). Stimulated by country-specific recommendations from the European Union in 2017, the Spanish government along with regional administrations turned to the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF), which had a legal mandate to evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of programs, and the authority to undertake reviews and interact with other levels of government. Lacking the requisite capacity for spending reviews, the regional administrations had previously commissioned independent reviews by the AIReF within a well-defined scope. The central government also sought to launch a three-year spending review in accordance with EU principles for multi-year reviews, and it was able to rely upon the authority and credibility of the AIReF to undertake them. Trust had been built by the AIReF developing a governance model that maintains the confidence of sponsors and partners in its reviews and draws together the requisite expertise for each review. It coordinated the strategic program reviews and liaised with relevant ministries at different levels of government to secure data and insights, developed protocols to maintain confidentiality where necessary, and had groundwork undertaken by consultants and experts (Escriva 2022). The first three-year spending review, focused on public subsidies, was launched in 2018 and operationalized into seven projects. In 2019 a second stage focused on four projects: hospital expenses, hiring incentives, transport infrastructure, and central tax benefits. For each of the reviews, AIReF held extensive bilateral and multilateral meetings with relevant departments and agencies from all levels of government. Much of this relational work involved overcoming the natural resistance of government entities to external review, securing access to critical data, and ensuring the data were comparable. Appointing the best experts from inside and outside government to inform the reviews was seen as critical for not only designing a credible review at the outset, but also for building dedicated internal review capacity in partner departments and agencies (Escriva 2022: 48-49).

Conclusion: Canadian Experience in Comparative Perspective

These international experiences are instructive for three reasons. First, they underscore what is distinctive about the Canadian approach to spending reviews. Although Canada’s experience since the 1980s is varied, Curran (2016) correctly observes that its experience has “thus far been one of ad hoc, one-off government-wide exercises conducted within extremely short timeframes, often in response to external pressures.” Second, international experiences point to important design considerations which remind us that, in contrast to the most recent Canadian experience, spending reviews can be: more open (in the sense of involving external experts and public consultations); more forward-looking (as opposed to focusing on lowering costs, efficiencies or shorter-term reallocations); ventured in sectors across levels of government; and develop standing review capabilities and repertoires. Finally, Tryggvadottir (2022) suggests that reviews are most effective in achieving lasting success with as little disruption as possible when they are regular, systematic, and part of an embedded system.

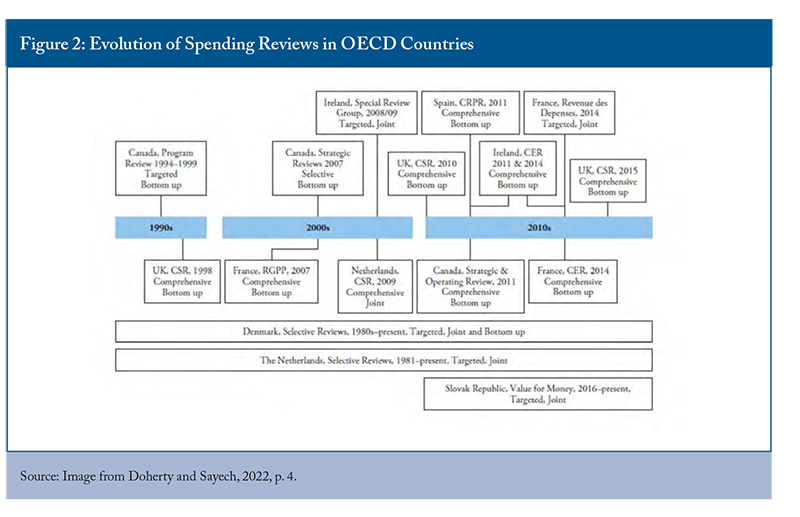

We selected the four above jurisdictions because their stand-alone spending or strategic review processes provide diverse examples for consideration when designing new approaches to Canadian reviews. However, Doherty and Sayegh’s (2022) diagram (Figure 2) shows that there are other jurisdictions worth mentioning. Some governments – like the United Kingdom – have long-held repertoires (though episodically invoked) for creating central task forces for this purpose, where central-agency capacities are rapidly expanded by drawing on a combination of civil servants, consultants, academics, and other experts to review submissions. South Korea and Japan rely on systematic spending reviews subsumed under broader annual budgetary and performance regimes, animated by central budget targets (OECD 2005). In South Korea, departments rank programs and reallocate savings to new priorities based on their reviews (Jung 2022). In Japan, the Administrative Project Review involves an annual review of 5,000 programs, with a smaller group of programs selected by the Headquarters for the Promotion of Administrative Reform in the Cabinet Secretariat for more in-depth review – involving public meetings – undertaken by officials and external experts.

Design Considerations

This section delineates design considerations that we have drawn from the literature and these case-studies. These do not constitute recommendations,

but rather, identify various elements that must be considered when delineating a spending or strategic review. Each element points to several options that should be evaluated with respect to political context, stated purpose of review, and primary decision points. The key design considerations are as follows:

- Political leadership. The single-most important design consideration is that – whatever their objectives and approach – strategic or spending reviews must have the full backing and interest of the prime minister and the minister of finance. Ministers and public servants must understand that the reviews are a government priority and that decisions must flow from the reviews. This requires engaging, often confronting, ministers and the governing party caucus. Typically, review secretariats are situated in Finance or Treasury central agencies, though sometimes the cabinet office, and usually the minister of finance is the de facto lead minister. However, the prime minister must be seen as actively supporting the minister of finance and participating in key decisions of the ministerial vetting committee and ultimate cabinet decisions. Given the many other demands on the prime minister’s time, effectively incorporating the PM into this process is a key design consideration. There are important lessons to learn by reviewing how the UK prime minister’s time was allocated in support of the prime minister’s delivery unit under the Blair government (Barber 2008).

- Central administrative capacity. Central agencies do not often know much about the performance of policies and programs delivered by other departments and agencies. Central agencies are better understood as having key roles in vetting proposals and establishing guidelines and budget authorities for new policies and programs. They will rely heavily on the reporting and data that other departments and agencies supply, monitoring how they are performing against expectation. Such monitoring often proceeds at a very high level, in part because of the breadth of responsibility and limited capacity of central agencies. Asking departments and agencies to meet savings targets, and allocating those savings into future budgets is one matter for central agencies. But moving into deeper spending and strategic reviews of policies and programs – not to mention exploration of interactions across programs and levels of government – is quite another. It requires thinking carefully about “scaling up.” This might range from central agencies expanding their own capacity or finding ways to access and lever additional expertise either from elsewhere in the public service or externally.

- Defining the focus of the reviews. Reviews can vary considerably with respect to their focus, resulting in several important strategic and design implications. First, the focus will determine the criteria, data, and analysis required from departments and agencies, and determine the nature of vetting from central agencies and other experts, as well as the timelines needed for credible analysis and vetting. Second, developing clarity about the focus of the reviews is necessary for ensuring public servants and other experts gather pertinent information and undertake sufficiently credible analysis with manageable timelines and tabling options for the consideration of ministers. Finally, defining the focus is critical for getting political and public expectations in order about the outcomes of the reviews. Conflicting objectives – or interpretations of those objectives – make it less likely that a government can produce credible results and declare success, as happened with the Nielsen Task Force on Program Reviews under the Mulroney government.

- Department/agency expectations and assembling information. Departments and agencies are enormous repositories of administrative data and regularly produce several budget and performance reports, evaluations, audits, and other mandated reporting (like their departmental planning and results reports) to executive teams, department audit advisory committees, and central agencies. However, these lines of data and reporting are typically for disparate purposes and rarely assembled in meaningful ways to inform spending or strategic reviews that demand a defined focus. These purposes may be tied to the Expenditure Management System (EMS), the purpose of which is to track programmatic expenditures rather than review the nature of such expenditures. Design considerations will involve how one might improve the readiness of departments and agencies to integrate the data and insights they have at hand, often for reviews with very different purposes. An equally important design consideration is the requisite timeline. Typically, spending and strategic reviews proceed according to tight schedules, independent of EMS expectations. Unless the reviews are selective and highly focused it will be difficult for departments and agencies to produce credible work. This means that department and agency heads might consider anticipating reviews and building new capabilities for looking across streams of information, and perhaps developing matrix or task-force structures and repertoires while using systems such as the EMS as an input information source. Finally, instituting reviews – even if they are different in focus and scope – builds capacity for subsequent reviews.

- Scaling up or down the breadth and focus of reviews. A critical design consideration is how comprehensive and multi-faceted a review ought to be. We have argued that reviews should have a clear focus, but at times there might be a strong case for two or three reinforcing objectives (i.e., reducing/containing spending outlays, alternative service delivery, and policy alignment). Likewise, spending and strategic reviews might only focus on certain kinds of programs, economizing on the time of ministers and central agencies, but also allowing the public service to recruit and deploy the right analytic talent to undertake the reviews, and perhaps engage external experts and stakeholders as advisors. Although governments may prefer to be selective for the aforementioned reasons, others – especially new governments or those encountering crises – may opt for comprehensive approaches. This is because there may be political blow-back if a government singles out certain programs or seeks to make a statement by designating a limit to growth in spending. Under these circumstances, the decisions may not be as well informed, but the objectives are clear, even if the effects of the decisions may accrue years later.

- Engaging the public and other jurisdictions. The Canadian and international experience shows that the public can be variously engaged in spending reviews, and more broadly in strategic reviews. Securing support in principle for spending reviews, especially comprehensive ones, can be essential for generating and maintaining political and bureaucratic momentum in producing and implementing proposals. An important question is precisely when and how to engage the public: will they be engaged to set expectations, or to demonstrate the range of contending needs and interests at stake, or to review the package of proposals emanating from the reviews? Should governments rely on elected representatives or leaders of stakeholder groups or citizen forums? Many advocates and scholars favour more open and democratic reviews, but there are political and administrative realities to consider. Increasingly, forums are simply grandstands for projecting views and interests rather than occasions for dialogue and deliberation to inform a balanced approach.

- Engaging experts from inside and outside the government. Most often, spending and strategic reviews of various kinds require departments and agencies to undertake most of the heavy lifting due to their knowledge of the policies and programs they deliver and the stakeholders they benefit, along with their access to administrative data, evaluation, audit and performance reports. Experts are needed for two reasons. First, they are needed when human resources and essential skills are not available internally. Second, experts can also be invited to provide a “challenge function,” to scrutinize and question the work being done. Canadian governments have utilized different models of this challenge function. The Nielsen Task Force placed a heavy reliance on external experts to produce and initially vet reports. Conversely, Chretien’s Program Review relied on a deputy minister committee to initially vet reports, and the Harper Government’s reviews relied heavily on consultants. Many OECD countries lead review teams with external experts, essentially partially internalizing the challenge function, along with higher order challenge reviews (Tryggvadottir 2022).

- Building a culture of review and learning. Institutionalizing repertoires means that those involved see reviews as natural and expected. In the context of spending or strategic reviews, this requires developing a political and bureaucratic culture that sees reviews as part of the normal rhythms of governance and good public management, and important for both substantive and symbolic reasons. There is no practical use to undertaking systematic reviews if all of the work will not be acknowledged and utilized. This quickly sends signals to those commissioning and undertaking the reviews that they are spinning wheels, which in turn creates incentives for incomplete, superficial, or shoddy analysis. Ascertaining the right focus and breadth of reviews for government priorities should not only ensure a receptive audience, but also prepare the repertoires and capabilities necessary for further expansions or alterations to the focus of reviews, as government priorities evolve.

All of these design considerations are important, but the Canadian and international experience suggest that strong political leadership and considered design are critical for building momentum and longer-term success. The scale and focus of reviews must be congruent with political priorities and the attention span of the government, otherwise ministers and officials will not commit. Identifying the appropriate coordinating capacity of central agencies will depend on the nature of the review. This will also dictate what data and information gets assembled by departments and agencies. The efficient channeling of attention and resources, and the general credibility of the review process, hinge on clear and purposeful design.

Proposed Approach

Our premise is that Canadian governments will need to undertake more significant spending reviews than the one currently in progress. Efforts to whittle down planned spending hearken back to the 1980s when the Mulroney government announced a succession of “cuts exercises” in response to inflation, higher interest rates, and compounding deficits. This is what observers called “repetitive budgeting” (Caiden and Wildavsky 1974), then associated with developing countries, which never truly came to grips with the underlying fiscal challenges. There remained a need to make more difficult and sophisticated decisions that might enable movement in new directions. This ultimately led to the more dramatic Program Review launched by the Chretien government, which dealt with the deficit and led to surpluses and the government investing in new programs. Despite this success, and later reviews by the Harper government to maintain fiscal discipline, these efforts were only episodic. The time has come for Canadian governments of all political stripes to institutionalize systematic spending or strategic reviews as needed.

To institutionalize these reviews, we have identified three opportunities, or windows, which would build on the future cuts exercise now in motion or any subsequent kind of review:

- The Trudeau government, in the last year of its mandate, looks to expand the reviews in the next budget cycle;

- The leadership of the Canadian Public Service works to develop a more credible approach to spending or strategic reviews as part of the transition advice in preparation for a federal election and a new government; and

- The first round of budgets under a new government mandate, regardless of party, will announce a substantial spending or strategic review, with variations in design depending on which party forms the government.

With this in mind, a general strategy should involve a combination of building capacity across departments and agencies and nurturing the interest of political leaders. While there may not be agreement on fiscal policy, there seems to be some agreement among political parties that public spending should be reined in, if only to fund other priorities (Campbell 2023). Although several factors inhibit incorporating reviews into regular repertoires as noted, budget exercises tend to adopt five-year cycles that could be better incorporated within internal reviews as one process for gathering information on the section of the budget within the federal purview.

Building capacity in central agencies. To launch, coordinate, and report on spending or strategic reviews in a high-quality manner, the Canadian government needs to establish stable but flexible staff capabilities for coordination. In most jurisdictions, such capabilities are situated in the finance or treasury department, but they can be located in the cabinet office. In Canada, because of the special configuration of the central agency apparatus, the best location would be within the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Determining the focus and breadth of reviews. To ensure a government is well-served by a spending or strategic review, there should be clarity about focus and purpose and how many departments and agencies (or policy domains) will be considered. The type of review will depend on the stage of the government’s mandate, its priorities, and the evolving external context. Over the years Canada’s episodic reviews have varied considerably in focus and timing. By “determining focus,” we mean the delineation of purpose and objective. By “determining breadth,” we mean a delineation of policy domains and/or departments and agencies designated for review. This matters because the vetting and decision-making processes must be prepared to meaningfully review and make determinations. When specifying the focus and breadth of the next round of reviews, a government should consider its willingness to entertain advice, as well as the quality of review needed to inform decisions. Specification of review priorities should flow from the spring budget.

Preparing departments and agencies for reviews. The responsibility for preparing departments and agencies rests with the government and the review secretariat, in addition to departmental and agency leadership. The review secretariat must promulgate clear and timely purpose and guidelines, due dates, and updates, and serve as a resource for entities with varying capabilities. Departments and agencies must be proactive and anticipate the data and analysis that might inform reviews and identify how to best integrate disparate data before the focus of the next round of reviews is announced. Regardless of the review’s focus, departmental and agency leadership can view the process as an opportunity to secure overdue decisions on key pressures, move forward plans or accelerate proposals for promising innovation, and identify new approaches for dealing with emerging challenges. Likewise, early on leaders can identify a liaising group and determine the internal talent that might be best to assign to coordinate the reviews, contact the outside experts who could best assist, and ascertain whether department audit and evaluation advisory committees can review materials. Even if certain imagined reviews do not materialize, such groundwork could inform subsequent cabinet and Treasury Board submissions.

Developing an external constituency for reviews. Once vetted, the ultimate users of spending or strategic review reports in Canada have typically been designated ministerial review committees and the full cabinet (the exception was the Nielsen Task Force). Governments, of course, do not necessarily have to accept the advice, and they may defer acting on some options until they perceive a timelier opportunity. While we appreciate the hesitancy of governments to make public such advice, there are four reasons why sharing review reports might be advisable:

- They have educative value and demonstrate to external constituencies the difficult decisions and trade-offs a government must make;

- It is important to show that the public service and other contributing experts carried out valuable work;

- They identify the mounting pressures, re-allocation possibilities, and emerging challenges which all political parties and pundits should consider and address;

- They provide evidence to external constituencies of an ongoing plan over the short to medium term.

Such reports, perhaps in summary form, can be submitted to key parliamentary committees (i.e., House of Commons Finance and Public Accounts committees) after the spring budget wherein final decisions are announced. This would make the essence of the reviews public and subject to commentary by the Parliamentary Budget Office, think tanks, interest groups, and columnists, furthering the goal of transparency in government and fostering a different kind of discourse in the public domain. Even if some stakeholder groups and Opposition critics might use the review reports to make the government and review teams uncomfortable, the reality is that all stakeholder groups ought to feel uncomfortable given the pressures at hand.

Our proposed approach for institutionalizing spending or strategic reviews augments the regular cycle of priority-setting and budget-making of Canadian governments (see Figure 3). While it does require adding a modest capability in departments and agencies at the centre of government, it would also be leveraging data and information already at hand through the EMS and other systems (arguably under-utilized). The proposed model for the review secretariat, with a relatively stable set of staff, ensures continuity and institutional memory, but also allows for flexibility with respect to the focus and breadth of the next review, and greatly increases the chances of good management. A regular review cycle with more public reporting is ultimately about creating a different kind of governance culture and reporting system in Canada; the aim being the improvement of department and agency planning.

Conclusions

The time is ripe for the Canadian government to institutionalize annual systematic spending and/or strategic review repertoires into the regular budgetary and reporting cycle. If the current government is not interested in doing so, the Public Service could nevertheless ready itself since history suggests that a new government will want to undertake some kind of stock-take exercise, especially if there is a change of political party. The deficit and debt must be controlled in light of existing commitments and envisioned roll-out of federal programs. There are real risks of further interest rate increases and higher debt interest outlays. Several leading economists have expressed concern that the debt-GDP ratio (currently at about 48 percent) and the interest-cost ratios (currently approaching 10 percent) exceed comfortable levels over the remainder of this decade, as spending is outpacing promised fiscal management aims (Lester and Laurin 2023; Dodge and Dion 2023).

Not only are spending or strategic reviews critical elements of sound fiscal policy and public management, but they will also provide additional opportunities for innovation in the delivery of programs and the factoring of over-the-horizon investments into expenditure decision-making, rather than simply paring back existing policies and programs. We have also argued here that such a system makes for good politics.

Strong leadership and engagement from the prime minister and other key cabinet members is essential. What we are proposing involves developing a new governance culture over successive governments, one that could stimulate and release the energy and acumen of the Public Service. It is important to develop the fortitude to deal with the inevitable resistance of stakeholder groups of policies and programs, along with criticism of opposition parties. However, we assert that instituting annual spending or strategic reviews more regularly and publicly will, on balance, lead to better public understanding of the current and future policy challenges confronting governments.

Leaders of the federal Public Service cannot wait for a prime minister to fire a starting pistol on spending or strategic reviews. They must take stock of what was learned from the 2022-2024 spending review, assess previous Canadian and international experience, and lay the groundwork for institutionalizing spending or strategic reviews. Getting the design right is critical to success. We have suggested that there are three windows of opportunity: preparing for the 2024 spring budget; transition planning and advice for the next election and government; and preparing for a new government’s first budget and likely expenditure or operating review. As done previously,

REFERENCES

Barber, B. 2008. “The Near-Death of Democracy.” World Policy Journal 25(4): 145-151.

BNN Bloomberg. 2023. “Scotiabank excoriates Trudeau, Freeland over $43B spending boost.” March 29. Available at https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/scotiabank-excoriates-trudeau-freeland-over-43b-spending-boost-1.1902121.

Bourgon, J. 2009. Program Review: The Government of Canada’s experience eliminating the deficit, 1994-99: a Canadian case study. London and Waterloo: Institute for Government and Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Boyle, R., and M. Mulreany, 2015. “Managing Ireland’s budgets during the rise and fall of the ‘Celtic Tiger’.” In Wanna, J., Lindquist, E. and deVries, J., eds. The Global Financial Crisis and Its Budget Impacts in OECD Nations: Fiscal Responses and Future Challenges, Chapter 11, 284-308.

Caiden, N., and A. Wildavsky. 1974. Planning and Budgeting in Poor Countries. New York: John Wilen & Sons.

Campbell, Ian. 2023. “Fiscal state of provinces offers Ottawa a chance to push more centralization – if it chooses – says IRPP report.” The Hill Times, November 13.

Canada. 2011. Budget 2011: The Next Phase of Canada’s Economic Action Plan: A Low‐Tax Plan for Jobs and Growth. Ottawa: Supply and Services.

______. 2023. Budget 2023: A Made‐in‐Canada Plan: Strong Middle Class, Affordable Economy, Healthy Future. Ottawa: Supply and Services.

Catalano, G., and A.Erbacci. 2018, “A theoretical framework for spending review policies at a time of widespread recession.” OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 17/2.

Clark, I.D. 1994. “Restraint, renewal, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.” Canadian Public Administration 37:2, pp. 209-248.

Curran, R. 2016. “Why Trudeau needs to embrace expenditure reviews.” Policy Options (July 4, 2016).

______. 2019. “Returning to balanced budgets requires a careful game plan,” Policy Options (August 27).

Curry, B. 2023a. “Cabinet ministers given Oct. 2 deadline to cut $15 billion from spending plans.”. Globe and Mail (August 15).

______. 2023b. “Poilievre casts doubt on Liberal plan to shave $15-billion off spending.” Globe and Mail (August 15).

De Witte, N., and F. de Jager. 2020. “Spending Reviews in the Netherlands: Best Practices and Lessons Learned,” Presentation to Strategic Analysis Unit, Ministry of Finance, Netherlands.

Dodge, D., and R. Dion. 2023. “Assessing the Potential Risks to the Sustainability of the Government of Canada’s Current Fiscal Plan.” Bennett Jones and Business Council of Canada.

Doherty, L., and A. Sayegh. 2022. How to Design and Institutionalize Spending Reviews. Washington, D.C. International Monetary Fund.

Drummond D. 2023. “Bogus Spending Restraint is not Spending Restraint.” Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, April 12, 2023.

Dumaine, F. 2012. “When one must go: The Canadian experience with strategic review and judging program vsalue. New Directions for Evaluation, 133:65-75.

Escrivá, J.L. 2020. “How to conduct a spending review in a federal government setting?” In E. Bova, R. Ercoli and X. Vanden Bosch, eds. Spending Reviews: Some Insights from Practitioners. European Union Discussion Paper 135, pp. 44-49.

Government of Ireland. 2023a. Spending Review 2022.

______. 2023b. Policy information: The Spending Review.

______. (2023c). Department of Public Expenditure and Reform. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation/department-of-public-expenditure-and-reform

Government of the Netherlands. 2021. Coalition Agreement 2021-2025.

IFSD. 2017. “The Deficit Reduction Action Plan: Politics Versus Planning and Transparency in Government Finance.” Ottawa: Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy.

IMF. 2019. “Annual Report of the Executive Board: International Monetary Fund Annual Report 2019: Our Connected World.” 4 October.

___. 2022. “World Economic Outlook Report: Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis.”

Jung, S. M. 2022. “Participatory budgeting and government efficiency: Evidence from municipal governments in South Korea.” International Review of Administrative Sciences, 88(4): 1105-1123.

Kennedy, F., and J. Howlin. 2017. “Spending reviews in Ireland – Learning from experience.” OECD Journal on Budgeting, 16(2): 93-108.

Lester, J., and A. Laurin. 2023. “Ottawa Needs a New Approach to Fiscal Policy.” Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, E-Brief.

Lindquist, E.A. 1996. “Reshaping Governments and Communities: Should Program Reviews Remain Unilateral, Executive Exercises?” In A. Armit, and J. Bourgault, eds. Hard Choices or No Choices: Assessing Program Review. Toronto: Institute of Public Administration of Canada, 137-146.

______. 2022. “Canada’s Response to the Global Financial Crisis: Pivoting to the Economic Action Plan.” Ch. 23 in E. Lindquist, M. Howlett, G. Skogstad, G. Tellier and P. ‘t Hart, P. eds. Policy Success in Canada. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 457-477.

Lindquist, E.A., and R. P. Shepherd. 2023. “Spending reviews and the Government of Canada: Moving from Episodic to Institutionalized Capabilities and Repertoires.” Canadian Public Administration 66:3: 247-267.

Nelson, R.R., and S.G. Winter. 1985. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (Belknap Press).

OECD. 2005. “The Legal Framework for Budget Systems: An International Comparison.” OECD Journal on Budgeting, 4(3).

______. 2023. “Government at a Glance 2023.”

Paquet, G., and R. Shepherd, R. 1996. “The Program Review Process: A Deconstruction.” In How Ottawa Spends 1996/97: Life Under the Knife. Edited by G. Swimmer. Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 39-74.

Parliamentary Budget Office. 2022. “Economic and Fiscal Update 2021: Issues for Parliamentarians.”

PBO (Parliamentary Budget Office - Ireland). 2019. “The Irish Spending Review: Suggestions from International Experiences.” Dublin: PBO.

Rendell, M. 2023. “Higher cost of servicing debt putting Canadian government in a bind.” Globe and Mail (September 2).

Robinson, M. 2014. “Spending reviews.” OECD Journal on Budgeting, vol. 13/2.

Robinson, M. 2022. “Public finances after the Covid-19 pandemic.” OECD Journal on Budgeting, 22(3), 1-43.

Ruane, F. 2021. “Introducing evidence into policy making in Ireland.” In J. Hogan and M. P. Murphy, eds. “Policy analysis in Ireland.” Bristol: Policy Press, 63-76.

Shepherd, R.P. 2018. “Expenditure Reviews and the Federal Experience: Program Evaluation and Its Contribution to Assurance Provision.” Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation 32:3: 347–70.

______. 2022. “Internal governmental performance and accountability in Canada: Insights and lessons for post-pandemic improvement.” Canadian Public Administration, 65:3: 516-37.

Shepherd, R.P, E.A. Lindquist, and D. Simsovic. 2022. “New approach needed for reviewing government spending post-pandemic.” Policy Options (March 21).

Tellier, G. 2022. “The Canadian Federal 1994–1996 Program Review: Appraising a Success 25 Years Later.” Ch. 21 in Lindquist, E., Howlett, M., Skogstad, G., Tellier, G., and ‘t Hart, P. eds. Policy Success in Canada. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 416-437.

Tryggvadottir, Á. 2022. “OECD Best Practices for Spending Reviews.” OECD Journal on Budgeting, 22(1).

Van Nispen, F. K. 2016. “Policy analysis in times of austerity: A cross-national comparison of spending reviews,” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 18(5): 479-501.

Wells, P. 2011. “Strategic Review: What did the Government Cut?” Maclean’s (June 7).

Wilson, V.S. 1988. “What Legacy? The Nielsen Task Force Program Review.” In Graham, K.A. ed. How Ottawa Spends, 1988/89: The Conservatives Heading into the Stretch. Ottawa: Carleton University Press.

Zielinsky, W., A. Tryggvadottir, and E. Lau. 2021. “Conducting Rapid Spending Reviews to Identify Measures for Budget Balancing: Approaches, Challenges, and Recommendations.” PEMPAL Budget Community of Practice, Program and Performance Budgeting Working Group, World Bank.

Notes: