Home / Publications / Research / Home Advantage: Helping Financial Institutions Prepare for Financial Distress Amidst Rising Geopolitical Tensions

- Research

- |

Home Advantage: Helping Financial Institutions Prepare for Financial Distress Amidst Rising Geopolitical Tensions

Summary:

| Citation | Mark Zelmer. 2025. "Home Advantage: Helping Financial Institutions Prepare for Financial Distress Amidst Rising Geopolitical Tensions." ###. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Home Advantage: Helping Financial Institutions Prepare for Financial Distress Amidst Rising Geopolitical Tensions – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Home Advantage: Helping Financial Institutions Prepare for Financial Distress Amidst Rising Geopolitical Tensions |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/home-advantage-helping-financial-institutions-prepare-for-financial-distress-amidst-rising-geopolitical-tensions/ |

| Published Date: | September 25, 2025 |

| Accessed Date: | January 31, 2026 |

Outline

Outline

Authors

Related Topics

Files

For all media inquiries, including requests for reports or interviews:

by Mark Zelmer

-

Rising geopolitical tensions may make it more challenging to facilitate an orderly recovery or resolution of internationally active Canadian financial institutions in the event they encounter distress.

-

Foreign authorities are likely to continue to prevent the repatriation of surplus assets from their jurisdictions in times of stress until their own creditors have been satisfied. This is despite the post-financial crisis reforms introduced to encourage more cross-border cooperation in the management of distressed financial institutions.

-

This paper proposes some steps to encourage major Canadian financial institutions to keep more of their surplus capital and liquidity at home in Canada so that foreign jurisdictions would have less leverage over their Canadian counterparts should any of them encounter stress in the future.

-

It also highlights the need for more information about how interconnected parent institutions are with their foreign entities.

Introduction

The global rules-based system of laws and minimum standards that emerged 80 years ago in the wake of World War II is under threat. Rising geopolitical tensions, plus a United States that is turning inward and becoming less willing to serve as its anchor, are combining to threaten the future viability of this system. In this new world, tariffs and various forms of financial measures are increasingly being used by the United States as weapons to achieve domestic and international goals, including a major reset in that country’s relationship with Canada. As a result, it would be prudent to assume that foreign regulators and judicial systems may become less able or willing to cooperate with their Canadian counterparts to facilitate an orderly recovery or resolution of an internationally active Canadian financial institution in distress.11 To be fair, there have always been limits on the extent to which officials in foreign jurisdictions are able to cooperate with one another given they are unlikely to agree to any measures that would harm their own financial systems. These trends could potentially make it more challenging to help such institutions recover in times of stress or facilitate their orderly resolution and exit from the financial system if recovery ceases to be a viable option.

This risk is especially acute for Canada because some of our major financial institutions have very large operations in the United States. For the purposes of our discussion, we focus on the global activities of the six major Canadian banks22 The six major banks are: Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), Toronto-Dominion Bank (TD), Bank of Nova Scotia (BNS), Bank of Montreal (BMO), Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), and National Bank of Canada (NBC). These banks have all been designated as systemically important in Canada, plus RBC and TD have been designated as globally systemically important. As such, the failure of any of these banks potentially could seriously damage the financial system and broader economy. That said, the issues raised in this paper and our recommendations would apply to all Canadian financial institutions that are internationally active. For example, the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) has designated Manulife, Sun Life, Canada Life and Intact Financial as internationally active insurance groups or IAIGs. OSFI has committed to ensuring that those four insurers implement resolution plans as well. to make our points, given that they are all internationally active. But the lessons we draw can also be applied to other internationally active financial institutions based in Canada, given that they, too, have large operations in the United States and other regions around the world.

Canada’s six major banks have large credit exposures and investments abroad. They also carry significant investments in foreign securities and other assets on their domestic balance sheets. To the extent that these investments are held in foreign financial infrastructure or foreign custody accounts, there is a risk that they too could be potentially blocked or ring-fenced (i.e., frozen) by foreign regulators and courts, should financial market participants and other private stakeholders become concerned about the solvency of those institutions.33 There are two related, but distinct, meanings of the term “ring fence” in banking regulation and supervision. One is to structure (or restructure) a bank so that its consumer and commercial banking operations are bankruptcy-remote from its investment banking operations. This has nothing necessarily to do with the cross-border issues discussed in this paper. The other, which is the focus of this paper, is to temporarily prevent the parts of an internationally active bank that are in a particular country from transferring assets to the home country operations of that bank. This ring-fencing risk may make it difficult for Canadian regulators to ensure that these banks have ready access to enough assets to fully back the claims of depositors and other creditors based in Canada.

In addition to these financial linkages, most of these six banks also have large foreign operations through their branches and subsidiaries in the United States and other jurisdictions that are integrated to varying extents with their operations here in Canada.

While the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) has reportedly been having conversations with the six major banks about their management of geopolitical risk, this paper offers some ideas on how internationally active Canadian financial institutions and policymakers could start to manage these risks. Its aim is to help provoke discussions on how our financial system should be structured going forward so that it, and Canada more broadly, can operate with confidence in this new world.

For example, in late 2023, OSFI introduced a new solo Total Loss Absorbency Capital (solo TLAC) requirement guideline for the six major banks.44 A companion solo capital guideline was also issued for the three major life insurers based in Canada. The idea behind solo TLAC is to ensure sufficient capital on a stand-alone, or solo, legal entity basis in Canada to support the resolution of the Canadian parent institution should it be required. Or, to put it simply, OSFI is seeking to ensure that these institutions are not only adequately capitalized on a global consolidated basis, but that the capital is distributed within the global corporate group in such a way as to ensure that the parent bank in Canada remains well capitalized.

This paper questions whether the calibration of the solo TLAC requirements should be reviewed. We suggest that the risk weights applied to parent bank exposures to foreign branches and subsidiaries may need to be tightened, given the changes that have taken place in Canada’s relationship with the US since they were first set. They also appear to be very generous relative to the Bank of Nova Scotia’s experience in selling its Argentinian operations more than 20 years ago and compared to the solo capital requirements imposed by many other jurisdictions. When considering any changes, OSFI may also wish to consider whether there are any other elements that could also be adjusted in light of concerns that have been expressed by industry members about their stringency.

To be clear, we are not going so far as to advocate that major Canadian banks need to carry more common equity capital. Instead, we are simply suggesting, in the spirit of OSFI’s focus on solo TLAC, that those institutions may need to consider making changes to the mix in their sources of debt funding. With some simplifying assumptions, we calculate that the issuing of more bail-in bonds – the cheapest form of TLAC – to increase such capital could ensure banks’ investments in their foreign subsidiaries would be fully capitalized. This would not meaningfully increase the cost of funds to the banks and, therefore, to the cost of credit supplied to the economy.

This paper also proposes some additional steps that could be taken to encourage major Canadian financial institutions to retain more of their surplus capital and liquidity55 In other words, assets on the books of the local branches and subsidiaries incorporated in their jurisdictions that are greater than the sum of those entities’ liabilities and the capital required to meet local regulatory requirements. in Canada. The purpose: to safeguard the interests of Canadian stakeholders and reduce the leverage that foreign authorities would otherwise have in international discussions surrounding future cross-border recovery or resolution operations. One might wonder why we are proposing such changes at a time when, as a country, we are looking for ways to encourage economic growth through the promotion of more competition in the financial system and reducing unnecessary regulation. We don’t view these changes as mutually exclusive. Stability and growth go hand in hand. On the former, it is critical to promote changes in regulatory requirements that would help enhance financial stability in Canada, especially in the current environment where we are witnessing unprecedented changes taking place in our relations with the United States.

Major Canadian Banks Have Large International Operations

The six major Canadian banks have a long history of operating abroad. For example, BMO opened its first permanent international branch in New York in 1859, followed by a London, England branch in 1870. Meanwhile, BNS and RBC have operated in the Caribbean since the late 19th century; the latter also opened a branch in London, England, in 1910.66 Information on the history of Canadian bank international operations was extracted from bank websites. The expansion of Canadian banks abroad has enabled them to participate in, and profit from, what has been a huge expansion in cross-border financial intermediation in recent decades.

Perhaps the most striking development has been the expansion of Canadian banks into the United States over the past 40 years. Both BMO and TD have acquired United States banks and built large regional banking networks on the Eastern seaboard (TD) and western United States (BMO) that are now starting to rival the size of their Canadian operations, both in terms of assets and revenues.

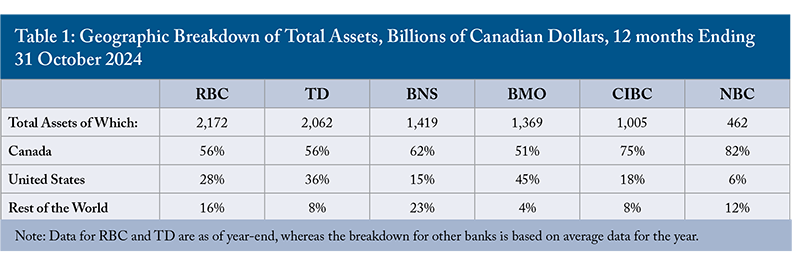

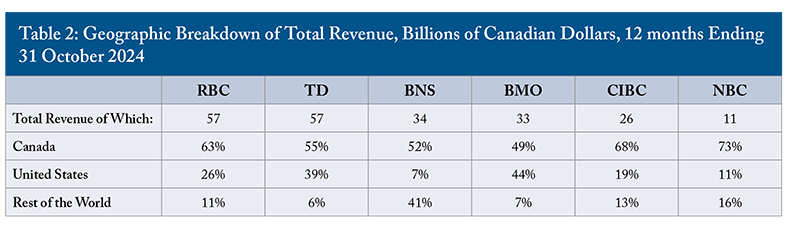

Tables 1 and 2 present some basic statistics on the size and importance of the foreign operations for major Canadian banks, using data on the geographic distribution of their assets77 Arguably, it would be better to focus on the geographic distribution of total credit exposures rather than simply the geographic distribution of balance sheet assets to capture both on-balance-sheet and off-balance-sheet exposures and potential credit exposures from undrawn credit lines and derivatives activities. However, these data were not readily available for all six banks. That said, the geographic distributions were fairly similar for both assets and total credit exposures for those banks for which both sets of data were readily available. and revenues88 We focused on revenues rather than net income to avoid distortions that may arise from how provisions for credit losses are allocated across countries and the extraordinary losses incurred by TD in its US operations in 2024. published in their 2024 financial statements. Key points to note are that all six banks have significant international activities, as evidenced by the amount of assets owned outside of Canada, as well as in terms of revenues generated from their international activities.

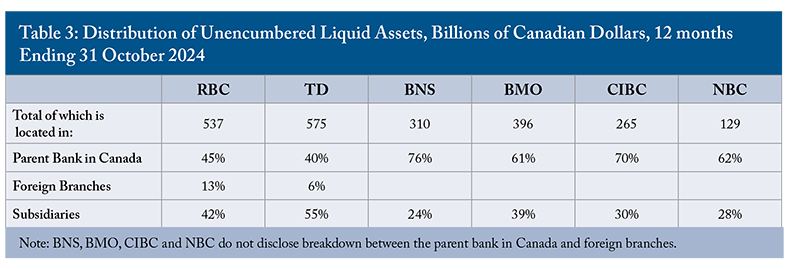

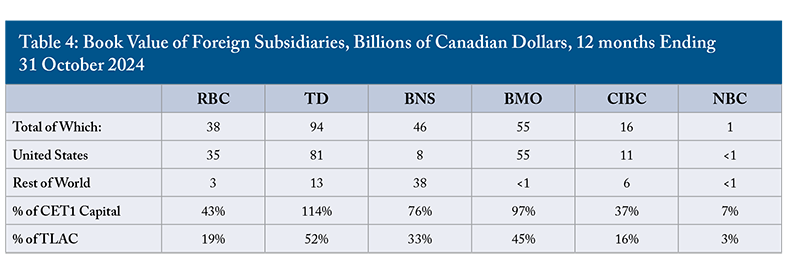

It is also worth paying some attention to how each bank allocates its liquidity and capital, given that this allocation can become quite important in times of stress. Some basic data in this regard are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The former table summarizes the distribution of unencumbered liquid assets (i.e., assets on the books of a bank that have not been pledged as collateral and can be readily sold to meet demands for cash from depositors and other creditors) among the parent bank, its foreign branches,99 As we will see later in the paper, foreign branches matter too because any assets held in those branches that back capital that is surplus to local regulatory requirements could be at risk of being frozen or ring-fenced by foreign authorities to fully satisfy first the claims of all creditors in their jurisdictions if the parent Canadian bank needs to be resolved. and its subsidiaries.1010 In the case of subsidiaries, we would only want to focus on how much unencumbered liquid assets are held in foreign subsidiaries for our purposes, not all subsidiaries. However, most banks do not publicly disclose a breakdown between their domestic and foreign subsidiaries. Meanwhile, the latter table summarizes the size of each bank’s investment in its foreign subsidiaries as measured by their book values and relative to the size of each bank’s Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital and TLAC bases.

We see that a significant share of each bank’s unencumbered liquid assets is booked in their foreign branches and subsidiaries; and that TD, BNS, and BMO each have very large investments in their foreign subsidiaries relative to their own (parent bank) CET1 capital and TLAC bases.

What we have identified, so far, are some basic insights into the financial ties of the six major banks to the United States and other foreign jurisdictions. But how integrated are their domestic operations with their foreign operations in practice? And, how difficult would it be to untangle those interconnections should the need arise in times of stress?

This is where things get very challenging. None of the banks disclose the information that one would need to begin formulating an opinion on these questions. Presumably, such information is contained within the recovery and resolution plans that the banks maintain with (independent) OSFI and the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), respectively. But those plans are not disclosed publicly, given the highly commercially-sensitive information they contain. Thus, it is not possible for an external observer to assess the adequacy of those plans and how they would propose to disentangle these interconnections in a resolution scenario.

One thing we do know from recent experience: Korstrom (2024) reported that it took about a year for RBC to plan and execute the migration of HSBC Bank Canada into RBC, from the time when that deal was agreed in late November 2022 to the closing date in March 2024. This timeframe allowed RBC to smoothly migrate over 780,000 clients and 4,500 employees to RBC, along with five business lines and over 125 branches. If this experience is any guide, one can surmise that smoothly untangling the foreign operations from a parent bank would be no easy feat and would likely require a fair amount of time; something that might be in short supply if the bank was experiencing stress.

Foreign Authorities Are Likely to Continue Engaging in Ring-fencing

Internationally active financial institutions have traditionally operated on the assumption that they can deploy capital and liquidity as they see fit to maximize profits. This is, of course, subject to managing and pricing for the associated risks; respecting local laws and regulatory requirements regarding the amount of capital and liquidity that local entities need to hold in their jurisdictions; plus respecting any restrictions more generally on the ability to transfer funds across borders, such as any local foreign exchange controls restricting the movement of funds across borders. But in doing so, these institutions assume that they will continue to operate as a going concern, meaning they pay little attention to the risk that their surplus capital and liquidity held abroad might be blocked if they encounter stress and need to be resolved. Indeed, some Canadian banks, e.g., BMO and TD, seem to implicitly consider both Canada and the United States to be their home markets, given that they discuss country risk in their annual reports in

terms of exposures outside of Canada and the United States.

Ring-fencing risk in times of stress, however, took on added importance in 2008 when economic and market pressures pushed major banks like Fortis Bank and Lehman Brothers into unplanned and uncoordinated failures (Ervin 2018). Those “crash-landing” failures surprised many and imposed losses on entities in both home and host countries. Out of that experience came the expression that banks are “international in life, but national in death.” Box 1 explains how, when an internationally active bank is approaching failure and needs to be resolved, a mad scramble can ensue as authorities in each jurisdiction intervene to take control of, or ring-fence, the local assets and operations of branches or subsidiaries in their jurisdiction. The aim of local authorities in such situations is to protect the local operations of the failing institution and reduce the risk of losses to their own domestic deposit holders and other creditors, and potential damage to their own national interests.1111 TD’s recent troubles show that restrictions on the transfer of funds by foreign regulators can also be imposed when banks are financially sound but have local shortcomings. Their 2024 annual report notes that in accordance with the terms of the orders that TD entered into with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Reserve in the United States, the boards of directors of the bank’s US banking legal entities will be required to certify to the OCC that the bank has allocated appropriate resources and staffing to the remediation required by the orders before declaring or paying dividends, engaging in share repurchases, or making any other capital distribution. One can surmise that if US regulators are willing to impose such restrictions on an institution that is clearly still operating as a going-concern, they would be even more willing to do so if the solvency of the institution was in doubt.

Central bankers and bank regulators have been attuned to this risk for many years. Goodhart (2011) documents how the disorderly failure of Herstatt Bank in West Germany in 1974 led to the creation of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Basel Concordat, which set out the initial understanding on the roles of home and host supervisors in overseeing internationally active banks. As time marched on, these reforms were followed by the creation of international supervisory colleges that brought together supervisors from key jurisdictions for each bank to build relationships and coordinate on cross-border supervisory issues.

The Basel Core Principles for Effective Bank Supervision, which provide a more comprehensive basis for encouraging cross-border supervisory cooperation, were then introduced in 1997. (They have been repeatedly updated since then as lessons were learned from various financial crises). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank started assessing the observance of them by the international community of bank regulators in 1999, following the Asian debt crisis. But, as noted above, the need for cross-border cooperation in resolution remains an outstanding issue that only started to be addressed after the world was reminded by the 2007-2009 global financial crisis how financial institutions are, once more, ultimately national in death.

That experience led to the introduction of the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB’s)1212 The Financial Stability Board was established by G20 leaders in the wake of the global financial crisis to promote international financial stability. It does so by coordinating national financial authorities (finance ministries, central banks and financial regulators) plus international standard-setting bodies as they work toward developing strong regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies. It fosters a level playing field by encouraging coherent implementation of these policies across sectors and jurisdictions. The FSB, working through its members, seeks to strengthen financial systems and increase the stability of international financial markets. The policies developed in the pursuit of this agenda are implemented by jurisdictions and national authorities (Source: FSB website). Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes, which were endorsed by G20 leaders in 2011.1313 The Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions set out the core elements that the FSB considers to be necessary for an effective resolution regime. They include 12 essential features that should be part of the resolution regimes of all jurisdictions. The FSB believes that their implementation should allow authorities to resolve financial institutions in an orderly manner without taxpayer exposure to loss from solvency support, while maintaining continuity of their vital economic functions. Concurrent with the introduction of the Key Attributes was the formation of international crisis management groups for banks that have been designated by the FSB as globally systemically important and the introduction of TLAC or bail-in debt requirements for systemically important banks (including the six major banks here in Canada).

An important feature of those requirements is the need for parent banks to pre-position some TLAC debt in their foreign subsidiaries that have been deemed to be material entities within the corporate group. This pre-positioning was done to give local host regulators some comfort that they can access additional capital to resolve the local entities of an internationally active banking group should the need arise in resolution. It was thought that such pre-positioning would encourage local authorities to be more cooperative in the resolution of the whole banking group in times of stress and reduce the incentives for them to engage in ring-fencing.

The effectiveness of these new measures in reducing the risk of ring-fencing in times of stress has yet to be fully tested. For example, Swiss authorities decided not to use them when they dealt with the failure of Credit Suisse in 2023. Instead, they chose to facilitate the takeover of that bank by UBS. Thus, we do not know if foreign jurisdictions would have ring-fenced the local operations of Credit Suisse had the Swiss authorities opted instead to use the new measures.

Here in Canada, OSFI was quick to take control of the assets of Maple Bank’s Canadian branch in 2016 to protect Canadian depositors and creditors after the parent bank was closed by its German regulators.1414 See: CBC (2016). Similarly, OSFI quickly took control of the assets of the Canadian branch of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in 2023 to protect the interests of SVB’s Canadian creditors and facilitate an orderly transition of the Canadian branch to the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) bridge bank for the whole bank.1515 See: OSFI (2023a). That said, there is no evidence to suggest that OSFI’s actions disrupted the resolution of those two institutions.

Nevertheless, these events suggest that ring-fencing by local host bank regulators when an internationally active bank encounters stress remains alive and well despite the reforms that have been enacted over the past 15 years. Given that Canada ring-fenced Maple Bank’s Canadian branch, a very small foreign operation, we should not be surprised if the United States and other countries would be willing to ring-fence a much larger Canadian bank with many foreign depositors. The risk of such behaviour becomes more acute in the current geopolitical environment, where international cooperation is generally becoming more challenging, especially when it comes to dealing with the United States.

OSFI Solo TLAC Requirements a Welcome Addition, But Do They Go Far Enough?

OSFI appears to be attuned to this issue. In 2023, it introduced a new TLAC guideline for the six major banks that sets minimum loss-absorbency requirements for those institutions’ parent companies on a legal entity or solo basis as a complement to the group-wide consolidated TLAC requirements. The purpose of this new solo TLAC requirement is to ensure that a non-viable domestic systemically important bank (DSIB) has sufficient loss- absorbing capacity on a stand-alone, or solo, legal-entity basis to support its orderly resolution in the event that it cannot recover from a period of stress. Or, to put it simply, it is not sufficient in this new world for an internationally active bank to rely on having enough capital on a global consolidated basis to cover the claims of Canadian depositors and other domestic creditors. OSFI also needs to ensure there is enough capital and other loss-absorbing capacity from bail-in-able debt1616 Bail-in debt refers to specific types of bank debt that can be converted into equity (common shares) of a bank if the bank ceases to be viable and needs to be resolved. This process, known as a “bail-in,” is a mechanism to recapitalize a failing domestic systemically important bank (D-SIB) by having its creditors, rather than taxpayers, bear the losses. on the books of the parent bank legal entity here in Canada to ensure that Canadian depositors and other domestic creditors will be treated equitably in the event the parent bank is no longer viable on its own and needs to be resolved.

The new solo TLAC guideline is fairly comprehensive. In setting the minimum solo loss-absorbency requirements, it not only takes into account investments that the parent Canadian bank may have in its foreign bank subsidiaries but also factors in other forms of capital investments and debt that the subsidiaries may have issued to the parent bank. And it also takes account of any amounts that the parent bank may have to pay out to its foreign subsidiaries under any capital guarantees that the parent bank may have granted to them.

A key issue in the guideline, however, is the risk-weights applied to the parent bank’s exposures to its foreign branches and subsidiaries. Risk-weights of 300 percent are applied to the parent bank’s net exposures to its foreign branches and 325 percent to its exposures to foreign bank subsidiaries. That is broadly akin to assuming that the parent bank should be able to realize at least 35 percent of its net exposure to its foreign branches and at least 30 percent of its exposures to its foreign subsidiaries if those branches and subsidiaries need to be disposed of when the banking group has failed and needs to be resolved.1717 A simple mathematical example can be used to show how risk-weights translate into assumed minimum recovery rates. The minimum TLAC requirement is 21.5 percent of risk-weighted assets. So, if the exposure to a foreign bank subsidiary is risk-weighted at 325 percent, that is equivalent to saying that the parent bank needs to have 69.875 cents of capital (21.5% x 3.25) to cover $1 of exposure to the foreign subsidiary. Thus, the subsidiary could be sold for as little as 30.125 cents on the dollar before there would be any reduction in the bank’s reported TLAC ratio. OSFI and its foreign regulator counterparts can also require banks to privately carry even more capital than stipulated in the public requirements like the solo TLAC requirements through what is known as the Pillar 2 component of the Basel Framework. If a bank has a material exposure to a market that is considered politically risky, regulators can and often will encourage it to adjust its capital plan and carry more capital to cover that risk. The fact that additional capital is being carried for such risks, however, is not publicly disclosed, meaning that external observers only see the higher capital ratios without knowing why they are so high. Consequently, we do not recommend simply relying on Pillar 2 requirements to manage these issues on an ongoing basis because bank stakeholders will not have sufficient information to assess a bank’s exposure to ring-fencing risks in times of stress when such clarity would be highly desirable.

These risk weights may be reasonable on a going-concern basis when solvency is not in doubt and financial conditions are generally benign. For example, past experience, such as RBC’s recent purchase of HSBC Bank of Canada in 2024, has shown that healthy banking subsidiaries can usually be sold at a significant premium to their book value.

But OSFI’s risk weights are lower than those applied by many other jurisdictions in their own solo capital frameworks,1818 For example, the European Union, Japan, and the United Kingdom, to name a few. See McPhilemy and Vaughn (2016) for more details. In addition, the Swiss Federal Council announced on June 6, 2025, that it is actively considering going further, and has proposed that the full deduction of the investments in foreign subsidiaries from Common Equity Tier 1 capital be required for systemically important banks with foreign subsidiaries (i.e., UBS). where significant investments in foreign bank subsidiaries generally need to be fully deducted from CET1 capital if they exceed 10 percent of the parent bank’s CET1 capital base.1919 OSFI has not publicly explained why it chose to apply risk weights and base the calculation on TLAC capital rather than fully deduct exposures from CET1 capital as has been done by many other jurisdictions. This treatment is consistent with the principles of the Basel Framework, which encourage full deduction of significant investments in the equity of foreign bank subsidiaries that are included in the consolidated financial statements of a banking group. The purpose is to prevent double-counting of capital and reduce the risk of contagion between the parent bank and its consolidated banking subsidiaries.

More importantly, how does OSFI’s approach stack up for situations where a major bank’s financial condition may be in doubt?

Consider a situation where a sale of a branch or subsidiary might need to take place in a stressed financial environment, or if the issues that led to uncertainty about the financial condition of the parent bank are also present in its foreign branches and subsidiaries. In such cases, it is plausible that the sale price received might end up being much less than one-third of the book value of the exposures.2020 For example, when Bank of Nova Scotia abandoned its Quilmes bank subsidiary in Argentina in 2002 it sold the firm for a fraction of its original worth and took a $540 million after-tax charge to its income (CBC 2005). Such an outcome could be even more likely in cases where the foreign branches or subsidiaries are tightly integrated operationally with the parent bank, making it challenging for them to function on their own or as part of another banking group, at least in the short run.

Things could get even worse if authorities in the relevant foreign jurisdiction intervene to prevent funds from the dispositions being transferred back to the home country of the parent bank until they are satisfied that all claims in their jurisdiction have been settled to their satisfaction. If such risks crystallize, then the assumptions built into the guideline may not be sufficient to ensure that Canadian depositors and other creditors would be adequately protected in a resolution scenario.

The information presented in Box 2 suggests there is also a risk of potentially broader repercussions. For example, authorities in foreign jurisdictions might be tempted to try and freeze assets beneficially owned by a Canadian parent bank but which are held in local financial market infrastructure or in local custody accounts (e.g., publicly-traded US securities like US Treasury securities that are beneficially owned by a Canadian bank head-office in Toronto or Montreal but which are actually held on the bank’s behalf in the United States in the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation [DTCC]2121 DTCC is a central securities depository in the United States that performs the same functions as the Canadian Depository for Securities (CDS) here in Canada. or at a US custodian bank), with the aim of using them to satisfy the local claims on the parent bank’s branches and subsidiaries in their jurisdiction.2222 The fact that most financial assets are now usually held in electronic form at a US central securities depository, like DTCC for many US fixed-income securities, or held by a US custodial bank on behalf of a client like a commercial bank would make it operationally straightforward for US authorities to take steps to freeze such assets even though they are beneficially owned by a foreign entity like a Canadian bank. While such actions may not ultimately stand up to legal challenge, they could nevertheless complicate a recovery or resolution operation for the Canadian parent bank until they can be resolved in court.

This paper does not model whether OSFI’s solo TLAC requirements are sufficient. All in all, however, if we assume they were calibrated correctly in 2023 when they were originally set, it is fair to ask whether they should be recalibrated and rendered more stringent in light of the changes that have taken place in Canada’s relationship with the United States, where Canadian financial institutions have significant exposures. They also appear rather generous in light of the Bank of Nova Scotia’s experience in selling its Argentinian subsidiary more than 20 years ago and relative to the solo capital requirements imposed by many other countries.

In the Appendix, we use some simplifying assumptions to calculate the cost of the six major banks increasing the amount of TLAC they issue from the parent Canadian bank so that investments in their foreign subsidiaries would be fully capitalized (versus the current 70 percent level implied by the current risk-weights). Critically, we assume that banks are not asked to increase common equity capital and instead issue bail-in bonds, the cheapest form of TLAC. Our calculations indicate minimal increases in bank cost of funds, which would minimize any increase in the cost of credit to the Canadian economy.

The more that the six major Canadian banks can be encouraged to keep the assets that back their surplus capital and liquidity on the books of the parent banks here in Canada, the better-placed Canadian authorities would be to safeguard the interests of Canadian depositors and other creditors in any cross-border resolution operations involving those banks.

Ring-fencing Risks Can Be Managed Through Reforms

Given what we have learned so far, here are some ideas to stimulate discussion on how we can best move forward. These suggestions relate to disclosure and transparency, recalibration of solo loss-absorbency requirements, consideration of solo-liquidity requirements, and encouraging banks to keep more capital and liquidity in Canada.

1. Enhance disclosure of information by the six major internationally active Canadian banks so that there is scope for more market discipline on how recovery and resolution risks are managed by these institutions and their regulators.

This paper has noted the limited information in the public domain about how major Canadian banks are structured both in operational and financial terms, and how those structures may affect their recovery or resolution in times of stress, and indeed public confidence in the safety and soundness of the financial system more broadly. That has continued with OSFI’s new solo TLAC requirement guideline, which does not specify any public disclosure requirements that would help stakeholders better understand how those banks arrived at their assertions that they fully comply with the guideline’s requirements.

This lack of information may not seem to be very important in the current environment where the banks are performing well, and their solvency is not in doubt. But should any of them encounter any serious difficulties in the future, financial market participants and other stakeholders may suddenly start to take an interest in these issues. That would not be the time to leave them on their own to draw their own conclusions based on minimal information. Instead, it would be better to educate them now about the international financial and operational structures of the banks when times are good, so that any views in times of stress would be more firmly anchored by concrete information.

Given the sensitivities surrounding this information and the highly competitive environment in which the major Canadian banks operate internationally, it would be best for Canada if such public disclosure requirements could be formulated and agreed internationally through either the Financial Stability Board or the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. That way, there would be international consistency on what is reported, and Canadian banks would not be placed at a disadvantage relative to their global peers.

2. OSFI should review the calibration of its solo loss-absorbency requirements guideline in light of recent geopolitical developments.

Considering the changes to the geopolitical environment since the introduction of the solo TLAC guideline, it is fair to infer that the assumptions that drove the calibration of the current risk-weights in that guideline have changed. In addition, the guideline is silent as to the risk that foreign jurisdictions may try to seize foreign assets for which the parent bank itself is the legal beneficial owner, but in fact are held offshore in foreign financial infrastructure and custody accounts. Consequently, this paper encourages OSFI to consider whether the guideline should be revised accordingly.

In reviewing whether to boost the solo TLAC requirements for the major Canadian banks, it is important to consider the potential effect of such a measure on the cost of funds for the banks in question and hence on the cost of supplying financial services in Canada. Unfortunately, there is not enough information available publicly to compute such a cost with any precision. But, as mentioned, a rough calculation presented in the Appendix using interest rates that prevailed in mid-2025 when this paper was written suggests that the impact might be fairly small, at least when financial markets are functioning smoothly. That said, such a change would need to be phased in over several years, given the large volume of new TLAC debt that would need to be issued by some of the banks. Given the uncertainty surrounding these calculations, we would encourage banks and their regulators to engage in more detailed scenario planning to see what could happen in a stress event where costs may rise sharply.

At the same time, OSFI may also wish to consider whether there are any other changes to the solo TLAC framework that are worth considering in light of the banking industry’s concern about the stringency of some elements.

3. OSFI should also consider paying closer attention to the solo liquidity position of major Canadian banks.

There is also the issue of liquidity requirements. All six major banks pay close attention to how their liquidity and funding requirements are managed both on a global consolidated and local legal entity basis. But, given how bank runs can destabilize even a solvent bank (witness Home Capital’s experience in 2017), it is important that OSFI and policymakers pay close attention to bank practices in this regard to ensure that they are closely attuned to the risk of surplus assets being frozen or ring-fenced by foreign authorities from a liquidity management perspective.

Thus, OSFI is encouraged to make sure it can quickly access data on the solo liquidity position of internationally active banks when the need arises. OSFI has taken some initial steps in this direction. In May 2025, it released a discussion paper (OSFI 2025b), which outlined some proposals for how it could enhance its oversight of the management of liquidity by banks through its supervisory process. One of them, which this paper supports, was a suggestion that banks be encouraged to implement an Internal Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Process (ILAAP) that would, among other things, require banks to manage the risk that restrictions could be introduced to impede the transfer of liquidity within their global banking groups.

4. Other public policy measures should also be considered to encourage banks to keep their surplus capital and liquidity in Canada.

Major banks are understandably keen to maximize their risk-adjusted profits in service to their shareholders. As a result, they may be eager to invest a large portion of the assets backing their surplus capital offshore to minimize tax and other expenses. However, as we have noted, this may come at the cost of making it more challenging to facilitate the recovery of the bank in times of stress or its resolution if recovery ceases to be an option. This cost may ultimately be paid by Canadians more generally, rather than by just the bank’s shareholders, if the bank ultimately needs to be resolved and removed from the financial system.

This begs the question of whether there are any tax or other public policy measures that the federal government could take beyond the prudential regulatory suggestions noted above to encourage banks to voluntarily hold the assets backing their surplus capital here in Canada. In this new geopolitical environment, we would as a society be well served to do what we can to reduce the leverage that foreign authorities can deploy should we ever have to coordinate with them in the management of a distressed Canadian financial institution. But we would encourage governments to first clearly identify the root cause of why banks are investing their surplus capital and liquidity offshore. That way, any new tax or other public measures can be clearly targeted at addressing the root cause to minimize the risk of unintended economic or financial stability consequences from the introduction of such measures.

Conclusion

Global political events are propelling us into a new geopolitical era that is likely to include major changes in Canada’s relations with the United States. Canada and our financial system need to adapt accordingly. Some of our internationally active financial institutions have been operating, at least implicitly, on the assumption that they have two home markets: Canada and the United States. That was perfectly understandable in the past when we could count on a stable economic and political relationship between our two countries and strong oversight by supervisory authorities in both countries. But it may no longer be prudent to count on such relationships going forward.

If one accepts that premise, then we need to step back and think about how all our internationally active Canadian financial institutions should be structured going forward as Canada seeks to redefine its place in the world. In the interest of stimulating discussion on this topic, this paper argues for the need to make sure that the structure of those institutions reduces the leverage that foreign regulators and courts would have over us in the (hopefully unlikely) event that any internationally-active Canadian financial institution should encounter stress in the future and need to be smoothly removed from the financial system. We focus on an assessment of the appropriateness of current TLAC rules.

In such a world, Canadian policymakers should consider taking steps to encourage our major banks and other internationally active financial institutions to hold more of the assets backing their surplus capital here in Canada so that they are not exposed to the risk of those assets being stranded abroad and locked down (ring-fenced) by foreign authorities. The latter would likely want to use them to first satisfy their own stakeholders in full before they hand them back; something that may ultimately push more losses back to Canada.

Finally, this paper has noted the need to gain a better understanding of how interconnected and interdependent the operations between Canadian parent financial institutions and their foreign branches and subsidiaries are and how challenging it might be to disentangle those links should the need arise in times of stress. While such interconnections have arisen naturally over the years as these financial institutions exploited their economies of scale and scope, they have made all those institutions more complex, which again may come back to haunt Canada in times of stress.

The world is changing. Canada and its financial system need to adapt accordingly. Better to do so now in a thoughtful way while time is still on our side. Punting the issue until we have a crisis to motivate change would be a recipe for chaos that rarely ends well. Canadians deserve better than that for situations where the risk is clearly foreseeable in advance.

Appendix: A Rough Calculation of the Cost of Revising Solo TLAC Requirements

As noted in the main text, the risk-weights used in OSFI’s solo TLAC requirements appear to be rather lenient for times of stress. This begs the question of what the financial cost would be of making them more stringent.

Unfortunately, we lack enough public information to perform such a calculation with any precision. However, we can offer a rough estimate with the help of a few simplifying assumptions.

For purposes of this calculation, let’s assume that the six major banks would need to increase the amount of TLAC they issue from the parent Canadian bank so that investments in their foreign subsidiaries would be fully capitalized (versus the current 70 percent level implied by the current risk-weights). This would be broadly consistent with the practice in many other jurisdictions where solo capital requirements for parent banks require that investments in foreign subsidiaries be fully deducted from Common Equity Tier 1 capital. Using the data presented in Table 4 of the main paper, it would suggest that the six Canadian banks would have to increase their TLAC by the following amounts:2323 The calculation is as follows: ((100% fully capitalized / 70% currently capitalized) – 1) x investments in foreign subsidiaries = increase in required TLAC in billion of Canadian dollars.

RBC: $16 billion, equivalent to 8% of its current TLAC base;

TD: $40 billion, equivalent to 22% of its current TLAC base;

BNS: $20 billion, equivalent to 14% of its current TLAC base;

BMO: $24 billion, equivalent to 19% of its current TLAC base;

CIBC: $7 billion, equivalent to 7% of its current TLAC base;

NBC: $429 million, equivalent to less than 1% of its current TLAC base.

Next, we assume that to meet this additional TLAC requirement the banks would likely prefer to issue more bail-in bonds (rather than common equity or other forms of capital) from the parent bank given that bail-in bonds would be the cheapest form of TLAC.

To keep things simple, let’s also assume for the sake of argument that the banks would issue more five-year bail-in bonds to satisfy the more stringent TLAC requirement, and offset this with a corresponding reduction in term deposits or guaranteed investment certificates (GICs). Of course, this would have the perverse impact of increasing the banks’ reliance on wholesale funding, which would not be prudent, especially in times of stress. Instead, one would expect that in practice the banks would likely look to offset the increase in bail-in bonds by reducing their issuance of secured wholesale funding by, for example, issuing fewer covered bonds, commercial mortgage-backed securities, and notes backed by credit card receivables and home equity lines of credit. But we are using GIC rates here to keep things simple, given that those rates are readily available.

An examination of interest rate data in mid-July, when financial markets were operating smoothly, suggests that five-year bail-in bonds for the six major banks yield about 75 basis points more than GIC rates of all tenors. Thus, the additional cost of funds on an annual basis would roughly follow:

RBC: $120 million, equivalent to roughly 0.006% of total assets;

TD: $300 million, equivalent to roughly 0.015% of total assets;

BNS: $150 million, equivalent to roughly 0.011% of total assets;

BMO: $180 million, equivalent to roughly 0.013% of total assets;

CIBC: $52.5 million, equivalent to roughly 0.005% of total assets;

NBC: $3 million, equivalent to less than 0.001% of total assets.

Thus, at first glance, it appears that there should not be much impact on the six major banks’ cost of funds, provided those banks are given enough time to expand their bail-in debt programs to satisfy the new requirements. That said, these results are highly dependent on our simple assumptions and the interest rate spreads that existed in a fairly calm market environment. Banks and their regulators would be well advised to engage in some scenario analysis to consider how these costs may change in a stress scenario.

The author extends gratitude to Mawakina Bafale, Carlo Campisi, Sophia Cote, Jamey Hubbs, Jeremy Kronick, David Longworth, Duncan Munn, Janis Sara, Daniel Schwanen, and several anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. The author retains responsibility for any errors and the views expressed, which should not be attributed to any organization with which the author is or has been associated.

REFERENCES

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Basel Framework. https://www.bis.org/basel_framework/.

BMO Financial Group. Annual Report 2024. https://www.bmo.com/ir/archive/en/bmo_ar2024.pdf.

Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation. 2017. “Canada Improves Information Sharing for Bank Failures.” CDIC media release. March 17. https://www.cdic.ca/cdic-news/canada-improves-information-sharing-for-bank-failures/#:~:text=OTTAWA%20%E2%80%93%20March%2017%2C%202017%20%E2%80%93,cross%2Dborder%20cooperation%20and%20coordination.

CBC News. 2005. “Scotiabank files $600M US claim against Argentina.” April 7. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/scotiabank-files-600m-us-claim-against-argentina-1.549674.

________. 2016. “OSFI takes control of Maple Bank assets in Canada.” February 10. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/maple-bank-osfi-1.3442595.

CIBC. Annual Report 2024. https://www.cibc.com/content/dam/cibc-public-assets/about-cibc/investor-relations/pdfs/quarterly-results/2024/ar-24-en.pdf.

Ervin, Wilson. 2018. “Understanding ‘ring-fencing’ and how it could make banking riskier.” Brookings Institution. February 7. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/understanding-ring-fencing-and-how-it-could-make-banking-riskier/.

Financial Stability Board. 2024. “Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions.” April 25. https://www.fsb.org/uploads/P250424-3.pdf.

Goodhart, Charles. 2011. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: A History of the Early Years 1974-1997. Cambridge U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Korstrom, Glen. 2024. “RBC integrates HSBC, reveals details about Vancouver banking hub.” Business Intelligence for B.C. https://www.biv.com/news/economy-law-politics/rbc-integrates-hsbc-reveals-details-about-vancouver-banking-hub-8746245#:~:text=%E2%80%9CAs%20we%20reopened%20during%20the,hitch%2C%20which%20was%20incredible.%E2%80%9D.

McPhilemy, Samuel, and Rory Vaughn. 2016. “The levels of application of prudential requirements: a comparative perspective.” Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 625, (October). https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/working-paper/2016/the-levels-of-application-of-prudential-requirements-a-comparative-perspective.

National Bank. Annual Report 2024. https://www.nbc.ca/content/dam/bnc/a-propos-de-nous/relations-investisseurs/assemblee-annuelle/2025/na-annual-report-2024.pdf.

Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions. 2023a. “Superintendent of Financial Institutions takes temporary control of Silicon Valley Bank’s Canadian branch.” News release. Ottawa. March 12. https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/en/news/superintendent-financial-institutions-takes-temporary-control-silicon-valley-banks-canadian-branch.

______________. 2023b. “Parental Stand-Alone (Solo) TLAC Framework for Domestic Systemically Important Banks (D-SIBs).” https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/en/guidance/guidance-library/parental-stand-alone-solo-tlac-framework-domestic-systemically-important-banks-sibs.

______________. 2025a. “Parental Stand-Alone (Solo) Capital Framework for Federally Regulated Life Insurers (2023).” https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/en/guidance/guidance-library/parental-stand-alone-solo-capital-framework-federally-regulated-life-insurers-2025.

______________. 2025b. “Pillar 2 Liquidity and Funding Risks: Designing an Internal Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Process for Canadian Deposit-Taking Institutions.” Discussion Paper. May 22. https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/2025-ilaap-pieal-discussion-en.pdf?v=1750428492945.

Royal Bank of Canada. Annual Report 2024. https://www.rbc.com/investor-relations/_assets-custom/pdf/ar_2024_e.pdf.

Scotiabank. Annual Report 2024. https://www.scotiabank.com/content/dam/scotiabank/corporate/BNS_Annual_Report_2024_EN.pdf.

Swiss Federal Council. 2025. “Federal Council draws lessons from Credit Suisse crisis and defines measures for banking stability.” Press release. June 6. https://www.news.admin.ch/en/newnsb/ty6FlsBuspE-AXC9ClLJt.

TD Bank. Annual Report 2024. https://www.td.com/content/dam/tdcom/canada/about-td/pdf/quarterly-results/2024/q4/2024-annual-report-en.pdf.

Related Publications

- Intelligence Memos