Home / Publications / Research / Accepting Asylum Claims Without a Hearing: A Critique of IRB’s “File Review” Policy

- Research

- |

Accepting Asylum Claims Without a Hearing: A Critique of IRB’s “File Review” Policy

Summary:

| Citation | James Yousif. 2026. "Accepting Asylum Claims Without a Hearing: A Critique of IRB’s “File Review” Policy." ###. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Accepting Asylum Claims Without a Hearing: A Critique of IRB’s “File Review” Policy – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Accepting Asylum Claims Without a Hearing: A Critique of IRB’s “File Review” Policy |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/accepting-asylum-claims-without-a-hearing-a-critique-of-irbs-file-review-policy/ |

| Published Date: | January 29, 2026 |

| Accessed Date: | January 30, 2026 |

Outline

Outline

Related Topics

Press Release

Files

For all media inquiries, including requests for reports or interviews:

- Since 2019, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) has accepted tens of thousands of asylum claims without an oral hearing through its “File Review” policy, using a paper-based process that may exempt entire categories of claims, defined by nationality and claim type, from the default requirement of in-person adjudication. The policy was launched as a pilot in 2017 during the Yeates Review, when the possible dissolution of the Refugee Protection Division was under consideration, and formally institutionalized in 2019.

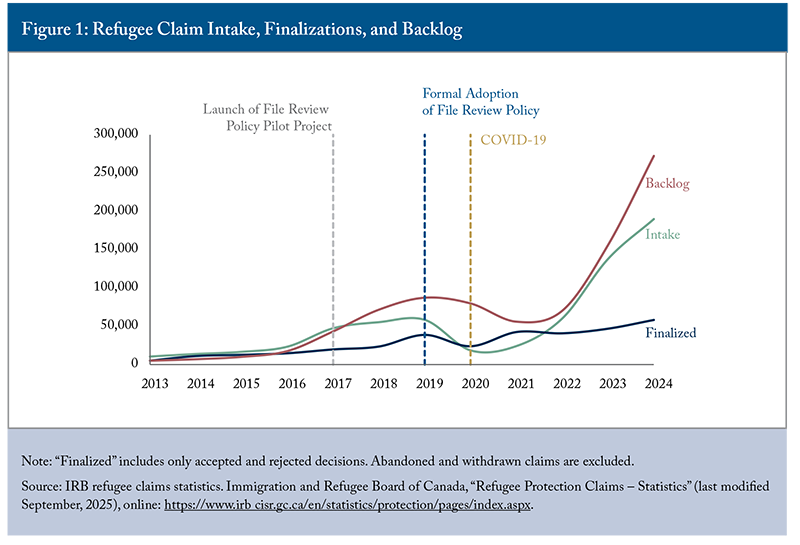

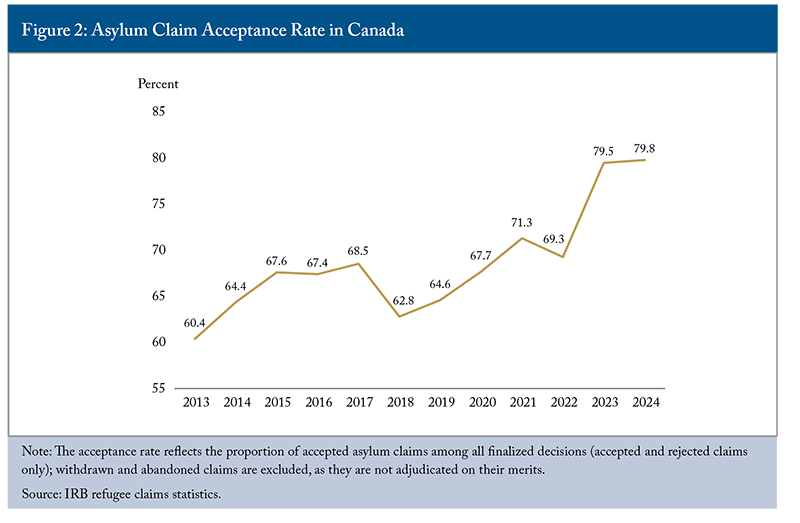

- Although introduced as an efficiency measure to accelerate decisionmaking and reduce the asylum claims backlog, File Review has not achieved this goal. Between 2016 and 2024, annual claim finalizations rose substantially as the IRB expanded staffing, resources, and procedures, including the introduction of File Review. However, intake continued to exceed capacity, and the pending claims backlog grew dramatically to nearly 300,000, as Canada’s overall asylum acceptance rate rose to roughly 80 percent – about double that of peer jurisdictions.

- In the absence of clear evidence of effectiveness, the report examines the policy’s legal, procedural, and security implications. By removing in-person questioning that tests credibility, detects fraud, and fulfills the IRB’s statutory role in identifying and flagging potential program integrity and security risk – functions that cannot be replicated through front-end security screening alone – File Review may have weakened adjudicative, program, and security integrity, and exceeded the IRB’s lawful authority.

- For these reasons, the report argues that the File Review policy should be brought to an end and the default requirement of questioning asylum claimants at a hearing should be restored.

Introduction

In recent years, a little-known policy of the Immigration and Refugee Board has quietly reshaped aspects of Canada’s asylum system in ways that raise important legal and governance concerns.

Canada’s asylum system is designed to protect individuals fleeing persecution.1Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27. It functions in an institutional setting that must balance fairness with administrative efficiency and fiscal sustainability. The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) was created in 1989, in the aftermath of the 1985 decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Singh v. Canada, which required that an oral hearing be provided to asylum claimants.2Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27. However, the Court did not prescribe how the government was to provide such a hearing; the government of the day opted to create a quasi-independent agency operating at arm’s length from ministers: the IRB.

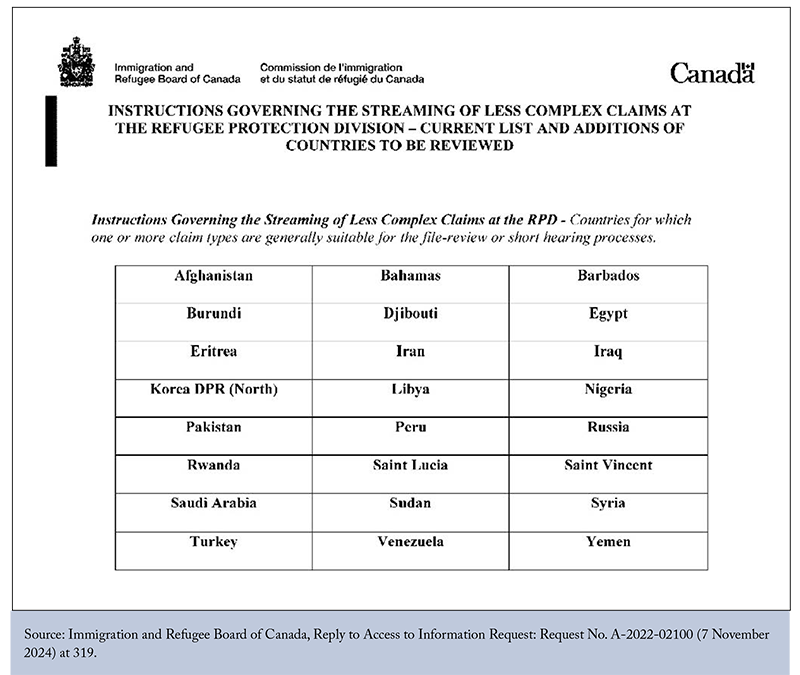

In 2019, the IRB implemented a policy that allows certain categories of asylum claims to be accepted without a hearing through a procedure they referred to as “File Review.” Using this policy, tens of thousands of asylum seekers have been rapidly accepted into Canada. This process was operationalized through the publication of a list of countries and claim types, an example of which is reproduced in Appendix B. Claims from countries on the IRB’s list could be accepted without a hearing. Recent Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) disclosures from the IRB have revealed many details about this policy.3See Appendix A. This paper relies in part on information obtained through a series of Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) requests. For the complete ATIP disclosure packages, please contact the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Communications and Access to Information Directorate, referencing the question numbers in Appendix A. This Commentary examines the legal, institutional, security, and economic implications of the IRB’s File Review policy.

While File Review was introduced as an efficiency measure to accelerate decisionmaking and reduce the asylum backlog, the available data provide no evidence that it achieved this goal. Despite substantial institutional growth – including major increases in IRB staffing and resources between 2016 and 2024 – the backlog expanded from roughly 17,000 to nearly 300,000 claims. During the same period, Canada’s overall asylum acceptance rate rose to about 80 percent, roughly double that of peer jurisdictions.

The basic problem with the policy is that some claimants are not questioned. By accepting asylum claims without a hearing, the policy may facilitate fraud and encourage more fraudulent claims. Asking questions is also a part of Canada’s security screening architecture and cannot be skipped without increasing national security risks. Accepting claims without questioning may also signal that it is easy to gain access to Canada through its asylum system.

This report argues that exempting entire categories of claims – defined by nationality or claim type – from the default requirement of a hearing raises questions about the scope of the IRB’s policymaking authority. The policy raises significant concerns about adjudicative integrity, national security, and legal authority. By potentially dispensing with hearings, File Review may have undermined the integrity of the system by removing in-person questioning that tests credibility, detects fraud, and fulfills statutory security screening functions. The policy may also exceed the IRB’s authority to enact unilaterally and may constrain adjudicators in ways contrary to administrative law principles. Given the absence of evidence that File Review achieved its goal, combined with these substantial legal, security, and procedural concerns, this report concludes that the policy should be brought to an end.

Resettlement and Asylum

Refugees come to Canada through two pathways: resettlement and asylum. This distinction is often misunderstood in media coverage.

A resettled refugee is selected while still outside of Canada. Canadian officials and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees are typically involved in a referral process, and the decision to grant refugee status and permit travel is made before arrival.

The asylum system is an entirely different process. A person seeking asylum must be physically present in Canada. Once a claim is made, they cannot be removed from Canada unless the claim is denied and any rights of appeal are exhausted.

The 1951 Refugee Convention requires Canada, in effect, to forgive any illegality involved in entering Canada for the purposes of making an asylum claim.4Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 28 July 1951, 189 UNTS 137, art. 31(1). In other circumstances, crossing into Canada on foot undetected or providing false information to obtain a visa may be grounds to be removed from Canada. But if an asylum claim is made, that consequence is suspended until the process concludes. This helps explain why asylum claims can be attractive to some who are not genuinely at risk of persecution, who simply wish to extend their stay in Canada – for example, foreign students whose visas are set to expire. By filing an asylum claim, visitors can delay departure from Canada for years while gaining access to publicly funded benefits and services.

Canada’s asylum system is among the most generous and procedurally complex in the world. Asylum claimants may be entitled to an initial hearing at the IRB, an appeal at the IRB, a Pre-Removal Risk Assessment, an application for Humanitarian and Compassionate consideration and, if all of these fail, an application to defer removal from Canada. Four of these processes, if declined, may result in applications for judicial review at the Federal Court.

With more than 295,000 asylum claims in the backlog at this time, the operational and resource implications of Canada’s asylum system are significant, affecting not only the IRB but also Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), the Department of Justice and the Federal Court.

The IRB and Public Servant Decisionmakers

With 2,500 employees and a budget of $350 million, the IRB is the largest administrative tribunal in Canada, with a regional presence in offices across the country.5Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, 2024 to 2025 Departmental Results Report (Ottawa: IRB, 2025), online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/reports-publications/planning-performance/Pages/departmental-results-report-2425-r.aspx. The Government of Canada has few direct lines of sight into the inner workings of the IRB. Unlike most organizations of that size and scope, the IRB does not report to ministers or deputy ministers because of its quasi-independent status. The IRB reports to Parliament through the minister of immigration, but even that minister cannot see the Board clearly. While the foreign policy implications of the asylum system are significant, the IRB enjoys direct relationships with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and other significant domestic and foreign policy stakeholders that are unmediated by the central authorities of government, whether political or departmental.

The Refugee Protection Division (RPD) of the IRB is responsible for adjudicating asylum claims. In 2010, the Balanced Refugee Reform Act (BRRA) introduced a permanent cadre of public servant decisionmakers at the RPD, and eliminated the appointment of board members by the Governor in Council (GIC).6Balanced Refugee Reform Act, S.C. 2010, c. 8. The RPD had accumulated a backlog of more than 62,000 claims. It was suggested that the GIC appointment process for RPD board members was partially responsible for this backlog, and that the stops and starts associated with adjudicators departing after the completion of their terms, and the lengthy appointments and onboarding process for new members, were slowing the RPD down. BRRA made the policy shift away from GIC-appointed board members at the RPD to public servant decisionmakers hired by IRB-run public service competitions. For clarity, references in this report to “board members,” “RPD decisionmakers,” and “adjudicators” refer to the same group of decisionmakers at the Refugee Protection Division.

The backlog of claims was segmented into what came to be called the “legacy” backlog, and the RPD was given a blank slate. With the funding and policy changes in BRRA, the IRB committed to finalizing not less than 23,500 asylum decisions per year going forward. The success of the broader legislative project relied upon this. However, in the five years that followed the implementation of the new asylum system this target was never met, and a new asylum claims backlog emerged at the RPD.

Yeates Review and the Threat of Dissolution

Despite years of concerted effort, new policy, additional funding, and a permanent staff of public servant adjudicators deployed across the country, the RPD remained unable to increase its decisionmaking output and meet its promised targets. In response to this, in 2017 the government initiated a comprehensive review of the asylum system, which was led by former Deputy Minister Neil Yeates. The participation of the Privy Council Office’s Machinery of Government Secretariat signalled that major structural reforms were under consideration, perhaps even the possibility of dissolving the RPD and transferring its function back to a line department, like IRCC.

This prospect caused alarm among refugee lawyers and advocacy groups, who strongly favoured the IRB model. In the midst of the review process, the Canadian Bar Association made the following comment:

As we await the results of the independent review, we are concerned that the government may consider reassigning responsibility for refugee determination from the IRB to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, or other non-adjudicative first level determination body. We understand this concern is shared by other stakeholders, including the Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers and the Canadian Council for Refugees.7Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02102 (7 November 2024) at 22.

It is a rare thing for an agency of government to face the prospect of its dissolution as an option at the outset of a review process. It may be an understatement to say that the RPD was motivated to rapidly increase its decision outputs in 2017.

Only Positive Decisions Can Be Made in Large Numbers Quickly

At an asylum hearing, if the board member determines that the evidence meets the legal test for refugee status, a positive decision can be rendered immediately, read into the audio recording of the hearing, and the file swiftly closed. The board member will have almost no further work on the file, no decision to write, and the IRB scores a plus-one finalization.

By contrast, negative decisions rejecting a claim of asylum require much more time and effort. Invariably, they must be written with great precision and care, because a negative decision will likely be appealed and closely scrutinized by immigration lawyers and adjudicators at the Refugee Appeal Division and the Federal Court of Canada. While negative decisions also score a plus-one for the IRB’s metrics, they require much more time and resources.

Accordingly, if the IRB was to quickly increase its rate of finalizations, it might prefer positive over negative decisions.

IRB Pilot Project: Accepting Asylum Claims Without Hearings

Facing the prospect of dissolution in the midst of the Yeates Review, the RPD expanded a project to accept asylum claims from a list of countries without a hearing. These claims were finalized “in chambers,” based solely on the paper application, without adjudicators ever meeting or questioning the asylum claimant.8Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02103 (7 November 2024) at 18. This policy helped the RPD to quickly increase its finalization statistics at a critical time, when the Yeates Review was deliberating upon the continued existence of the tribunal.

Also during this time, the RPD increased its overall volume of claims finalized, rates of acceptance and speed. The RPD increased its decision outputs from 14,793 in 2016 to 38,752 by 2019, a 162 percent increase.9Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Refugee Protection Claims — Statistics (last modified September 2025), online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/statistics/protection/pages/index.aspx. Concurrently, the number of new asylum claims surged, and the backlog more than quadrupled – from 17,537 in 2016 to 87,270 in 2019.

When the Yeates Review released its report on April 10, 2018, the report did not recommend dissolving the RPD.10Neil Yeates, Report of the Independent Review of the Immigration and Refugee Board: A Systems Management Approach to Asylum (Ottawa: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 10 April 2018), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/report-independent-review-immigration-and-refugee-board.html. The marked increase in the RPD’s rate of finalizations may have contributed to its survival.

Institutionalization of the Policy of File Review

The IRB made these measures permanent in January 2019.11The outbreak of COVID-19 occurred subsequently, and was not a factor in the formation of the policy. This was contained in a policy instrument called a Chairperson’s Instruction and given the nondescript title of “File Review.”12Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Instructions Governing the Streaming of Less Complex Claims at the Refugee Protection Division, online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/instructions-less-complex-claims.aspx. In the Chairperson’s Instruction, the IRB took a notable step. It openly published a list of countries and claim types that were eligible for a positive refugee determination without a hearing before an RPD adjudicator. The document stated as follows:

The RPD will identify whether a claim is suitable for the file-review process based on its assessment of the file and its consideration of the criteria set out in the Instructions. In order to assist parties and their counsel to understand which claims are likely to be selected for this process, the RPD publishes a list of claim types which it generally considers appropriate for the file-review process.13Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02100 (7 November 2024) at 161.

A list of eligible countries and claim types was published and revised over time (Country List).14The country lists were modified over time. Appendix B contains one example. See also: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request, Request No. A-2022-02100 at 64 (February 2019), 9248 (June 2021), 9419 (August 2021); Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request, Request No. A-2022-02101 at 54 (3 November 2020), 64 (31 January 2019); Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request, Request No. A-2022-02103 at 33, 39. The Country List remained accessible to the public from January 2019 until November 2020, at which time the IRB took the list down from public view.15Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02101 (7 November 2024) at 6; Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02100 (7 November 2024) at 315. While a list is no longer available to the public, the policy remains in effect, as does knowledge of it.16Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02104 (7 November 2024). Asylum-related information circulates through diaspora and community networks, human smugglers, and successful claimants, as well as lawyers and consultants whose clients continue to be accepted without a hearing. Research has shown that information transmitted through social networks – including family, friends, acquaintances and intermediaries such as agents or smugglers – plays a significant role in asylum seekers’ choice of a destination country.17Heaven Crawley and Jessica Hagen-Zanker, “Deciding Where to Go: Policies, People and Perceptions Shaping Destination Preferences” (2019) 57:1 International Migration 20-35.

Under this policy, claims from the countries and claim types on the Country List are not routed directly to board members for adjudication. They are first “triaged” by non-adjudicative IRB staff who assess the evidence in each file and decide whether the file is suitable to be adjudicated without a hearing. If so, the file is routed to a board member for a positive asylum decision without a hearing.18The file may also be routed into a “short hearing” process. The board member must review the file with a view to the possibility of accepting the claim without a hearing, after which they can either make a positive decision or return the file. It is important to note that triage into the File Review stream does not guarantee acceptance; many cases may be subsequently returned to the regular hearing process.19No publicly available statistics exist on the number of files that are returned for a hearing. One reviewer suggested that many files are returned for a hearing.

That means that a person from a country on the IRB’s Country List can enter Canada, make a claim for asylum, and receive a positive determination in the mail, without being asked a single question. In such cases, the policy of File Review effectively dispenses with the act of adjudication. It is as though the Board were treating asylum adjudication as a kind of weighted assessment designed to minimize false positives and false negatives in the aggregate, rather than a case-by-case determination grounded in direct adjudication. Between January 1, 2019 and February 28, 2023 (the scope of the ATIP request), the IRB accepted 24,599 asylum claimants into Canada without questioning them.20Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02104 (7 November 2024).

There is a circularity to the policy. The countries the IRB put on the Country List were those with the highest rates of acceptance for refugee status at the time the list was created. A threshold criterion for the first Country List was an acceptance rate of 80 percent or higher.21Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02100 (7 November 2024) at 297. But being placed on the Country List increases the likelihood that acceptance rates will remain high, so that a country once listed will tend to remain listed. The policy feeds itself with data that have been produced by the policy itself.

The policy of File Review raises significant concerns. It may make it easier for false or fraudulent claims to succeed. It appears to be outside the legal and policymaking authority of the IRB to enact unilaterally. It may constrain adjudicators in ways that are contrary to the law of administrative tribunals. It may also have compromised Canada’s national security by permitting claims to be accepted without sufficient scrutiny. Taken together, the policy’s potential economic and security implications warrant close attention.

Assessing the Available Data

As noted earlier, a pilot initiative permitting the acceptance of certain claims without a hearing was expanded in 2017 during the Yeates Review, formally adopted in January 2019, and remains in effect. The objective was to increase efficiency and help reduce the asylum backlog by expediting claims from certain countries with high acceptance rates. An examination of the available data reveals that this goal was not achieved. Instead, the policy coincided with a period in which the IRB’s capacity expanded but the backlog grew even more dramatically, raising questions about the utility and justification of accepting claims without hearings.

Between 2016 and 2024, the asylum backlog increased from 17,537 to 272,440 claims – an expansion of more than 1,450 percent. By September 2025, it reached a record 295,819 pending cases.22Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Refugee Protection Claims — Statistics (last modified September, 2025), online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/statistics/protection/pages/index.aspx. This occurred despite significant increases in the IRB’s processing capacity. Over the same period, annual claim finalizations rose from 14,793 in 2016 to 58,241 in 2024 – a 294 percent increase. This reflected a combination of expanded staffing23Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Population of the federal public service by department or agency (Human resources statistics, Government of Canada), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/innovation/human-resources-statistics/population-federal-public-service-department.html. (from 973 employees in 2016 to 2,579 in 2024 across the IRB, not only the RPD),24These staffing figures covered the entire IRB, not only RPD adjudicators. additional resources, and procedural changes, including File Review. However, these increases did not translate into backlog reduction. New asylum claims surged, especially after 2021, far outpacing the IRB’s enhanced capacity (Figure 1). The inventory has continued to climb in 2025, reaching a record 295,819 pending cases as of September 30, 2025.

Asylum claims increased from 17,537 claims in 2016 to 87,270 in 2019.25Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Refugee Protection Claims – Statistics (last modified September 2025), online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/statistics/protection/pages/index.aspx. The most substantial surge in both new claims and backlog growth occurred several years after File Review was institutionalized. New claims did not begin their dramatic surge until after 2021; between 2017 and 2021 they fluctuated between about 18,500 and 60,000 per year – with a sharp temporary decline in 2020–2021 during the COVID-19 period – before jumping to 137,947 in 2023 and 190,039 in 2024. Many factors contributed to this surge in asylum claims, including rising global migration pressures, the reopening of international travel after COVID-19, and changes in Canadian temporary immigration policies.

IRB Acceptance Rate Climbs

Also during this time, Canada’s overall acceptance rate increased from 62.8 percent in 2018 to 79.8 percent in 2024 (Figure 2). To place this in context, in 2024 France accepted 39 percent of claims, the UK accepted 47 percent, Germany accepted 44 percent, and Sweden accepted 40 percent.26European Council on Refugees and Exiles, “Overview of the Main Changes since the Previous Report Update – Germany” (June 2024), online: Asylum Information Database asylumineurope.org/reports/country/germany/overview-main-changes-previous-report-update; European Council on Refugees and Exiles, “Overview of the Main Changes since the Previous Report Update – Sweden” (April 2024), online: Asylum Information Database asylumineurope.org/reports/country/sweden/overview-main-changes-previous-report-update; European Council on Refugees and Exiles, “Overview of the Main Changes since the Previous Report Update – France” (May 2024), online: Asylum Information Database asylumineurope.org/reports/country/france/overview-main-changes-previous-report-update; House of Commons Library, Asylum Statistics (Research Briefing, December 2024), online: UK Parliament commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01403. The significance of this increase lies not in the trend alone, but in the extent to which it widened Canada’s divergence from peer jurisdictions, reinforcing Canada’s perception as a preferred asylum destination.

Asylum seekers respond to differences in asylum acceptance rates when selecting destination countries. Perceptions of the recognition rate – the likelihood of having an asylum claim accepted – significantly influence the selection by asylum seekers of their destination country.27Poppy James and Lucy Mayblin, Factors Influencing Asylum Destination Choice: A Review of the Evidence, Working Paper No 04/16.1 (University of Sheffield, 2016); Tetty Havinga and Anita Böcker, “Country of Asylum by Choice or by Chance: Asylum-Seekers in Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK” (1999) 25:1 Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43; Timothy J Hatton, “Seeking Asylum in Europe” (2004) 19:38 Economic Policy 5; Timothy J Hatton, “The Rise and Fall of Asylum: What Happened and Why?” (2009) 119:535 The Economic Journal F183; Eric Neumayer, “Asylum Recognition Rates in Western Europe: Their Determinants, Variation and Lack of Convergence” (2005) 49:1 Journal of Conflict Resolution 43; Gerard Keogh, “Modelling Asylum Migration Pull-Force Factors in the EU-15” (2013) 44:3 The Economic and Social Review 371. For a person considering where to make an asylum claim based on the likelihood of success, Canada may appear more attractive than peer jurisdictions because acceptance rates are roughly twice as high. This is sometimes referred to as a “pull factor,” a characteristic in a particular jurisdiction that attracts migration.

In the broader context of the IRB’s acceptance rate rising to 80 percent, maintaining the File Review policy, which permits the rapid acceptance of claims without a hearing, could reinforce perceptions of speed, success, and reduced scrutiny in Canada’s asylum system, relative to peer jurisdictions, and act as a pull factor.

Whether the expansion of the backlog was affected by File Review and the IRB’s high relative rate of acceptance, or whether these factors had no meaningful impact on backlog growth, cannot be determined from the available aggregate data. What can be determined is that File Review failed to achieve its primary objective of reducing the backlog. This failure provides the foundation for examining the policy’s other implications: if a policy does not deliver its intended benefits, the risks and concerns it raises assume greater importance in assessing whether it should continue.

Security Risks Associated with File Review

Canada Border Services Agency and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada have a mandate to intervene in asylum hearings at the IRB. CBSA focuses on security concerns, while IRCC officials address immigration program integrity. The ATIP disclosure indicates that officials at CBSA and IRCC were briefed on the policy of File Review prior to its implementation by the IRB. While some parts of the disclosure are redacted, the following security concern was noted:

The key issue is that the countries that can be expedited from an RPD point of view (high acceptance rate for refugees often due to conflict) are also countries that represent the highest concerns in terms of the serious inadmissibilities and 1(F) exclusions for the Public Safety Portfolio.28Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02102 (7 November 2024) at 53, 139.

This is a crucial observation. File Review expedites claims from countries with the highest rates of acceptance. Countries with conditions that result in the highest rates of acceptance for asylum claims are, as a result of those same conditions, among the most dangerous countries in the world.

The minister of public safety lists organizations that have facilitated or participated in terrorism.29Anti-Terrorism Act, S.C. 2001, c. 41. The list includes organizations that “have knowingly carried out, attempted to carry out, participated in or facilitated a terrorist activity.”30Instructions governing the streaming of less complex claims at the Refugee Protection Division, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/instructions-less-complex-claims.aspx. Of the countries in the sample of the IRB’s Country Lists in Appendix B, 13 are home to active terrorist organizations currently listed by the Government of Canada.

Front-End Security Screening Does Not Extinguish IRB’s Security Role

When the IRB announced the File Review policy in 2019, it indicated that all claims eligible for a paper-based positive decision would first be required to pass through Front-End Security Screening (FESS), which is an initial background check administered by CBSA. The implication was that FESS would address any security concerns related to the policy.31Instructions governing the streaming of less complex claims at the Refugee Protection Division, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/instructions-less-complex-claims.aspx. That assumption is incorrect.

FESS is only one aspect of Canada’s immigration-security framework, which occurs at the beginning of the process. FESS involves security agencies screening asylum applicants against various databases. The ability of FESS to detect a threat is only as good as the veracity of the identity documents underlying the claim, together with the ability to get a match against a relevant database. But identity documents may be forged, and the databases are not complete.

Since its adoption in 1951, the Refugee Convention has denied status to people who have engaged in serious criminality or political violence.32Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 28 July 1951, 189 UNTS 137, art. 1F (entered into force 22 April 1954). The RPD is required to identify and exclude such claims.33Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27, s 98. In practice, some asylum seekers who present a security risk to Canada may be identified only through in-person questioning at a hearing. Questioning each claimant in person at a hearing is itself an important part of Canada’s national security screening processes. A review of the paper record alone is not sufficient. The written application contains untested allegations that cannot be presumed to be true. Claim narratives may be fabricated, and supporting documents may be forged.

Careful questioning can reveal inconsistencies in complex or fabricated accounts. The provenance of documents can also be tested at a hearing by asking questions about them. There is no substitute for this process. Without in-person questioning to test credibility, probe inconsistencies, and assess the reliability of evidence, false or fraudulent claims may succeed and potential security risks may go undetected.

RPD board members have a responsibility to screen for security risks. This is reflected in Canadian law. During an asylum hearing, if questioning reveals information suggesting a potential security risk or raises possible exclusion, inadmissibility, ineligibility, or program-integrity concerns, the IRB board member is required to notify the minister of public safety or the minister of immigration and may be required to halt the proceeding. This reporting obligation is mandatory under rules 26, 27, and 28 of the RPD Rules.34Refugee Protection Division Rules, SOR/2012-256, r 26, 27, 28. The hearing at the RPD is itself a component of Canada’s national security and integrity-screening architecture. This function cannot be performed if the IRB accepts claims without meeting the claimant in person or asking any questions. Passing the initial FESS process does not displace this statutory role.

By potentially dispensing with hearings for certain nationalities or claim types, the File Review policy removes a layer of scrutiny that cannot be replicated through document review alone. While no system can detect every possible threat, eliminating one of the few tools capable of revealing deception, undisclosed criminality or misrepresentation, and of testing the veracity of documents in a system that is regularly subjected to attempted fraud, has the effect of increasing risk and diminishing program integrity ex ante.

File Review May Facilitate Fraud

Canada’s asylum system is used by people who are not at risk of persecution. Forged documents, fraud and misrepresentation are well-documented challenges across Canada’s immigration system and can be difficult to detect. According to IRCC, in 2024 the government investigated an average of over 9,000 suspected immigration fraud cases per month, resulting in thousands of refusals and enforcement actions.35Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Strengthening Immigration and Stopping Fraud (3 March 2025), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2025/03/strengthening-immigration-and-stopping-fraud.html. A recent report from the Canadian Immigration Lawyers Association similarly notes that IRCC refused over 52,000 temporary-residence applications for misrepresentation in the first six months of 2024 alone.36Canadian Immigration Lawyers Association, The State of Immigration Fraud in Canada (March 2025), online: https://cila.co/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/CILA-The-State-of-Immigration-Fraud-in-Canada.pdf. The report documents large-scale abuse of student and asylum pathways, including an estimated 50,000 “no-show” students and more than 14,000 asylum claims filed by students in the first nine months of 2024, highlighting both the scale and sophistication of fraudulent activity.

Fraudulent asylum claims may rely upon fabricated narratives of persecution, sometimes developed with the assistance of intermediaries such as human smugglers or community networks, and may use forged documents. These practices are difficult to identify, and many cases are never detected.

The File Review policy may facilitate and increase fraud and misrepresentation in Canada’s asylum system for two reasons. It signals in advance to false claimants, human smugglers and other intermediaries which specific countries and claim types may receive less scrutiny and faster processing, thereby identifying precisely which fabricated narratives are most likely to succeed. Second, it potentially removes the most basic safeguard in refugee adjudication: questioning the claimant.

To the extent that this policy has resulted in the acceptance of unfounded claims due to insufficient scrutiny, it has diverted finite resources away from the protection of bona fide refugees and thereby undermined the protection of human rights. It also has significant permanent downstream fiscal implications, as the acceptance of such claims entails ongoing cost implications for social programs at every level of government.

Soft Law and Administrative Tribunals

Administrative tribunals commonly develop policies and guidelines – sometimes referred to as “soft law” – to promote consistency in decisionmaking. However, there are limits on the ability of an administrative tribunal to make its own policies unilaterally, and limits also on what those policies may do. Some limits may be specified in the statute that creates the tribunal. Other limitations exist in administrative law principles. The IRB’s policy of File Review is a form of administrative soft law. The Board uses a variety of such instruments. The policy tool used to create File Review is a “Chairperson’s Instruction.”

The IRB’s website notes the following regarding Chairperson’s Instructions:

These Instructions provide direction to people employed by the IRB. The instructions tell employees what to do or what not to do in certain situations. Instructions focus on specific areas, such as file management, disclosing information, and appropriate communication between decision-makers and other IRB employees.37Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Chairperson’s Instructions, online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/chairperson-instructions.aspx.

A Chairperson’s Instruction does not require the approval of ministers or Cabinet. It may be developed and implemented by the IRB unilaterally, in part because it is intended to be limited to the internal operations of the tribunal.

Legal and Policymaking Authority

By default, Canadian law requires the IRB to hold a hearing in refugee protection claims.38Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27, s 170(b). By contrast, the File Review policy purports to declare that the IRB does not have to hold a hearing for certain countries and claim types.

The Chairperson’s Instruction establishing File Review notes several legal authorities. It cites section 170(f) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, which allows the IRB to accept a claim without an oral hearing. Section 170(f), however, operates on a case-by-case basis. It does not authorize a blanket exemption from hearings for entire categories of claims. By default the IRB “must” hold a hearing. Section 170(f) provides that it “may” accept a claim without a hearing in exceptional circumstances.

The Federal Court has affirmed that section 170(f) gives the IRB discretion in individual cases to waive the requirement for a hearing. In Bernataviciute v. Canada the Court stated that “the Board should be given a wide discretion in the administration of its legislation to determine cases where it is plain to see that the refugee claimant will be granted refugee status without the necessity of a hearing.”39Bernataviciute v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2019 FC 953. In Dragicevic v. Canada the Court similarly confirmed that section 170(f) is a discretionary power that must be exercised reasonably.40Dragicevic v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2019 FC 1310. Both cases imply the exercise of discretion in exceptional circumstances.

These cases addressed situations where individual claimants sought to compel the application of section 170(f). In both cases, the Court determined that the discretion to use 170(f) rests with the IRB and cannot be compelled by an applicant. Importantly, neither case addresses whether section 170(f) authorizes the categorical exemption of entire countries and claim types from the legal requirement to hold a hearing in a way that presumes and never tests their truthfulness. File Review may exceed the scope of section 170(f) by treating an exceptional, individualized discretion as a systematic processing mechanism.

The Chairperson’s Instruction also relies on sections 159(1)(a), (f), and (g) of IRPA, which grant the IRB authority to schedule hearings and manage its internal operations.41Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27, ss 159(1)(a), (f), (g). The Chairperson’s Instruction states:

The Chairperson of the IRB has supervision over the direction of the work and staff of the Board, the authority to apportion work and fix the place, date and time of proceedings as well as the authority to take any action that may be necessary to ensure that members of the Board are able to carry out their duties efficiently and without undue delay.42Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Instructions Governing the Streaming of Less Complex Claims at the Refugee Protection Division, online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/instructions-less-complex-claims.aspx#s4.

The IRB’s authority to manage its internal operations is not in dispute. The problem is that File Review goes well beyond tribunal operations. A policy of accepting broad categories of asylum seekers without a hearing directly affects the statutory mandate of CBSA and IRCC, both of which have an ongoing, direct role in monitoring for security and program integrity, but whose ability to intervene is triggered by a notification mechanism that depends upon claimants being questioned at a hearing.

The ATIP disclosure contains no record of any whole-of-government oversight or approval process for the policy of File Review.43See Appendix A, questions A-2022-02101 and A-2022-02102. The IRB appears to have acted unilaterally. This is unusual for a policy with implications for national security, immigration program integrity, and foreign policy.

The IRB does not have the unilateral authority to adopt a public policy that has the effect of nullifying the statutory notification and coordination mechanisms integral to the intervention mandates of the minister of immigration and the minister of public safety. A Chairperson’s Instruction, a form of IRB soft law limited to internal tribunal operations, is incapable of providing that degree of policy cover. Accordingly, the IRB may have exceeded its policymaking authority, in which case the policy may be ultra vires and perhaps unlawful. If that is correct, decisions reached in reliance on the policy may, at least in theory, be vulnerable to being set aside on judicial review.

Fettering

Administrative tribunal adjudicators, like those at the IRB, hear evidence, apply the law, and make independent decisions within the limited statutory scope of their tribunal’s mandate. The “discretion” of an administrative decisionmaker refers to the latitude of their freedom to choose between available legal outcomes. In the case of the Refugee Protection Division, that discretion means deciding whether to accept or reject a claim for asylum in Canada, that is, to render either a positive or a negative determination. When tribunal policies or guidelines unreasonably restrict an adjudicator’s discretion to make that choice in response to the facts of each case, their discretion is said to be “fettered.”

On the other hand, administrative tribunals commonly provide guidance to their adjudicators to encourage consistency in decisionmaking using “soft law,” which is both legally permitted and helpful to the statutory objectives of the tribunal. But the nature of this guidance must not go so far as to fetter: “If discretion is too tightly circumscribed by guidelines, the flexibility and judgment that are an integral part of discretion may be lost.”44Sara Blake, Administrative Law in Canada, 7th ed (Toronto: LexisNexis Canada, 2022) at 115.

Canadian law provides that the use of soft law instruments by administrative tribunals must not fetter adjudicators:

[G]uidelines, which are not regulations and do not have the force of law, cannot limit or qualify the scope of the discretion conferred by statute, or create a right to something that has been made discretionary by statute. The Minister may validly and properly indicate the kind of considerations by which he will be guided as a general rule in the exercise of his discretion ... but he cannot fetter his discretion by treating the guidelines as binding upon him and excluding other valid or relevant reasons for the exercise of his discretion.45Maple Lodge Farms Ltd v Canada, [1982] 2 SCR 2 at 7.

In Kanthasamy the Supreme Court of Canada determined that an immigration officer relied too heavily upon an operational guideline issued by the department, which caused them to fail to turn their mind to relevant facts and issues.46Kanthasamy v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2015 SCC 61, [2015] 3 SCR 909. The Court determined that this constituted fettering on the part of the immigration officer, and the decision was ruled to be invalid for that reason.

Note that fettering is unlawful. A reviewing court will invalidate such decisions. Fettering is akin to a jurisdictional failure – not a jurisdictional excess but rather the opposite – a failure to use the adjudicative power conferred by statute to consider all of the relevant facts and decide from among all available outcomes.

The issue of fettering and the IRB specifically came up in Thamotharem, in which the Federal Court of Appeal considered the validity of a guideline that specified the order of questioning during a hearing.47Thamotharem v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2007 FCA 198, [2008] 1 FCR 385 (FCA). The Federal Court of Appeal determined that a guideline specifying the order of questioning was within the authority of the IRB, in part because it did not fetter board members.

In Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers v Canada,48Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2021] 1 FCR 271, 2020 FCA 196 (CanLII). the validity of three IRB jurisdictional guides was challenged. Jurisdictional Guides are another form of IRB soft law. One of the arguments raised by the Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers was that these IRB policies had the effect of fettering IRB board members. In the course of rejecting this argument, the Federal Court of Appeal made the following comment about the distinction between a policy instrument that is helpful and lawful, as opposed to one that fetters:

[T]he line would be crossed when the language used in guidelines may be reasonably apprehended by decision makers or members of the general public to have the likely effect of either pressuring independent decision-makers to make particular factual findings or attenuating their impartiality in this regard. The same is true where such language may be reasonably apprehended to make it more difficult for independent decision-makers to make their own factual determinations. This is so even if it has been stated that the guidelines are not binding [emphasis added].49Ibid., at para 21.

In summary, the notion of fettering is particularly concerned with internal policies that interfere with fact-finding. It is not only the policy’s text that will determine whether it fetters, but also its effect.

File Review and Fettering

The policy of File Review may interfere with fact-finding and fetter the discretion of RPD board members. The policy of File Review has two moving parts: (i) a triage mechanism staffed by IRB personnel who are not board members, who assess the evidence in each file referred using the policy,50Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02100 (7 November 2024) at 365. and who determine whether to route it to (ii) a board member who is required by the policy to attempt to make a paper-based positive decision without holding a hearing.51Immigration and Refugee Board, Instructions Governing the Streaming of Less Complex Claims at the Refugee Protection Division (Ottawa: IRB, 2025), online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/instructions-less-complex-claims.aspx.

The fettering effect of the policy is baked into this structure. The triage unit only refers files it assesses to be suitable to be decided without a hearing. When a board member receives a referral under the policy, the act of referral conveys to the board member that triage staff have examined the evidence in the file and are of the opinion that it should be possible for the board member to make a positive decision accepting the claim for asylum without meeting the claimant or asking any questions. An evidentiary assessment and suggested outcome are implied in the act of referral. This necessarily affects the adjudicator’s view of the evidence and legal options by encouraging a fast, positive decision without a hearing.

At the moment of referral by the triage unit, the integrity of the adjudicative process is affected. The process is mandatory; board members are required to review the evidence in a referred file with a view to the possibility of rendering a positive decision without questioning the claimant. At the end of this process, they can decide that they are unable to make a decision without a hearing, but affected board members cannot prevent IRB triage staff, who are not adjudicators, from first reviewing the evidence in their files and then making implied recommendations to them with respect to findings of fact and substantive outcomes. The fact that board members have the option of returning a referred file at the end of this mandatory process does not cure the fettering effect of the policy. The result is interference with the independent, fact-finding role of adjudicators, and for that reason it may constitute fettering.

Unlike the guideline upheld in Thamotharem, which regulated only the order of questioning within a hearing, the File Review policy structures how and by whom factual assessments are made. As the Federal Court of Appeal emphasized in Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers v. Canada, the line is crossed where an internal policy may reasonably be apprehended to pressure adjudicators toward particular factual conclusions, attenuate their impartiality, or make it more difficult for them to conduct independent fact-finding, even where the policy is formally described as non-binding.

A Delegate Cannot Delegate

When Parliament, through statute, delegates to the adjudicators of an administrative tribunal the power to make decisions, that power cannot be subdelegated to another person. Parliament is presumed to delegate carefully and intentionally:

The purpose of the rule against subdelegation is to preserve the quality of decisions, ensure the fairness of decisions, and respect the intent of the legislature. The presumption behind the rule is that the legislature has chosen to delegate carefully, and another person may not possess the same knowledge, skills, or qualifications. Equally important is the fact that accountability for decisions may be compromised when decision-making takes place outside the established structure for the exercise of statutory powers.52Lorne Sossin and Emily Lawrence, Administrative Law in Practice: Principles and Advocacy (Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications, 2018) at 32.

The triage function of the File Review policy may contravene this principle. As noted above, triage staff assess evidence and make implied recommendations on substantive outcomes. However, the authority to determine the substantive outcome of an asylum hearing at the RPD, and in particular the authority to make findings of fact in that context, is a power that Parliament has delegated only to board members.53Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27, s 163. The effect of File Review is to bifurcate the fact-finding process into separate stages, delegating part of this role to IRB personnel who lack legal authority to adjudicate. The policy may thereby constitute an unlawful delegation of statutory authority.

Improper Consultation

There are limitations on the kinds of consultations an adjudicator can have with their tribunal colleagues before rendering a decision:

The evaluation of evidence must be done by those who heard it. All discussions with tribunal colleagues should be based on the findings of fact as determined by the adjudicators who heard the evidence.54Sara Blake, Administrative Law in Canada, 7th ed (Toronto: LexisNexis Canada, 2022) at 123.

The Supreme Court of Canada, in Consolidated Bathurst, addressed the issue of internal consultation within an administrative tribunal.55Consolidated-Bathurst Packaging Ltd v Canadian Labour Relations Board, [1990] 1 SCR 282, 1990 CanLII 132 (SCC). The Court determined that internal discussions on general policy issues are permissible, provided that adjudicators remain free to make their own findings of fact without pressure or influence. A consultation process may not include a discussion of factual issues.56Ibid., at para 94.

File Review requires triage staff, who are persons other than the adjudicator with statutory authority to decide a given case, to assess the evidence in each file and implicitly communicate their assessment of that evidence to the responsible board member through the act of referring the file. The effect of this process may result in an improper consultation regarding as-yet-undetermined findings of fact.

The Federal Court of Appeal has determined that a consultation process cannot be imposed by a superior level of authority within the administrative hierarchy, which is how the policy of File Review was implemented, through the instrument of a Chairperson’s Instruction.57Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2020 FCA 196 at para 61, citing Ellis-Don Ltd v Ontario (Labour Relations Board), 2001 SCC 4 at para 29.

Moreover, a consultative process cannot be mandatory: “[c]ompulsory consultation creates at the very least an appearance of a lack of independence, if not actual constraint.”58Tremblay v. Quebec (Commission des affaires sociales), [1992] 1 S.C.R. 952 at para 44. File Review is mandatory for affected board members. While they can and in many cases do eventually return a referred file for a regular hearing, they cannot opt out of a compulsory process in which non-adjudicative colleagues assess the sufficiency of the evidence in their files and convey that assessment to them through the act of referral.

Fettering, improper delegation, and inappropriate consultation each constitute breaches of the principle of procedural fairness in administrative law, which requires adjudicators to act free from bias or improper influence. Decisions reached in such circumstances are unlawful and may be overturned by a reviewing court.

Concerns Over Country Condition Evidence

The Research Directorate of the IRB curates and publishes a document package of country conditions for every country of origin for asylum claims, referred to as the National Documentation Package (NDP).59Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Policy on National Documentation Packages in Refugee Determination Proceedings (Ottawa: IRB, 2019), online: https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/national-documentation-packages.aspx. The NDP is marked as an exhibit and entered into the record of evidence in every asylum hearing at the RPD. It is the primary source of evidence relied upon by board members with respect to country conditions. While they may examine additional sources at their discretion, board members have no alternative but to use the NDP packages supplied to them by the tribunal.

The Research Directorate of the IRB is required to adhere to a standard of impartiality. The curation of the document packages must be objective, balanced, free from institutional bias, and accurately represent the range of credible and relevant sources on human rights and country conditions.

The ATIP disclosure suggests that the IRB may have modified the National Documentation Packages to facilitate the policy of File Review. IRB staff noted:

If claim types are added to the expedited process, the NDP must be revamped to reflect this change and to increase the overall utility of the NDP. The Adjudicative Strategy Committee recommends greater coordination between the Research Directorate in Ottawa and the regions, to ensure that documentation meets the needs of Members.60Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02103 (7 November 2024) at 19.

This statement raises concerns. It suggests that the document packages were altered to enhance their utility to the policy of File Review. Editing the NDPs in support of the policy would presumably mean making it easier to make a positive decision. The more documentary evidence of persecution and danger in the NDP, the easier it is to make a positive decision. By contrast, the greater the ambiguity or presence of conflicting indicators in the country condition evidence, the more difficult the adjudicative task becomes.

If the IRB modified the NDPs to increase their “utility” for a policy of rapidly accepting asylum claims, that would imply that the Research Directorate added documents to the packages that indicated elevated risk, and/or removed more ambiguous or nuanced sources. Selectively curating evidentiary records to support a policy that favours positive over negative outcomes is inconsistent with the adjudicative neutrality expected of a tribunal. Although the available disclosure is limited, this reference raises a governance concern that may warrant further scrutiny.

Application Criteria for Board Members

After the legislative changes in the Balanced Refugee Reform Act were implemented, the IRB began hiring public servant decisionmakers directly, now uncoupled from the oversight that had been provided by the Prime Minister’s Office, the Privy Council Office, the immigration minister’s office, IRCC, and the GIC-appointed staffing process. In the spring of 2011, the IRB ran a competition for 105 new public servant decisionmakers to staff the newly constituted Refugee Protection Division. The IRB advertised a competition for RPD board members in which candidates were required to have at least one of the following qualifications:

- Recent experience rendering decisions in a judicial or quasi-judicial process.

- Recent experience presenting cases before an administrative tribunal or court of law.

- Recent experience in conducting research or investigations in a quasi-judicial or judicial or immigration context.

- Recent experience in providing legal or mediation services in a quasi-judicial or judicial context.61Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Reply to Access to Information Request: Request No. A-2022-02096 (September 2024) (supplementary disclosure) at 123.

The education requirements were as follows:

- Degree in law from a recognized university.

- Degree in public administration.

- Degree in international relations.

- Degree in refugee studies.

- Degree in migration studies.62Ibid., at 124.

Ten years later, in 2021, having accumulated a massive and growing backlog and with the policy of File Review in effect, the IRB held another competition for RPD board members. This time, the IRB weakened the education and experience requirements significantly. The criteria for “Stream 1” of the 2021 competition for new board members were as follows:

- Graduation with a baccalaureate degree from a recognized post-secondary institution.

- At least one year of work experience drafting documents in a time-sensitive manner.

- At least one year of work experience managing multiple projects, files or cases that require organization, prioritizing and respecting at times short deadlines.63Ibid., at 44-46.

The IRB did not require legal training, adjudicative experience, or subject-matter expertise. This shift raises concerns. Lowering the professional qualifications required for new board members risks weakening the tribunal’s capacity to carry out its core functions. A person without legal or tribunal experience may also be less likely to identify administrative law constraints, such as fettering, and be more amenable to direction in the context of a policy like File Review, which may diminish adjudicative independence.

It may be worth considering how the Refugee Protection Division’s post-2010 staffing model may have contributed to the emergence of policies such as File Review, by replacing board members appointed by the Governor in Council with public servants hired directly by the IRB. While this change did not diminish the legal duty of adjudicative independence, it altered the institutional context in which that independence is exercised. A GIC-appointed board member confronted with a policy that interfered with their independent assessment of the evidence may have been in a stronger position to object to policies that were inconsistent with their statutory role.

Conclusion: The Policy of File Review Should be Brought to an End

The IRB failed to meet the target of 23,500 asylum finalizations per year, as promised in the context of the Balanced Refugee Reform Act of 2010, and by 2017 the RPD had accumulated another backlog. The Government of Canada commissioned the Yeates Review, which raised the possibility of dissolving the RPD. Against this backdrop, the IRB implemented File Review – a policy of rapidly accepting asylum claims from specific countries and claim types without a hearing – with the goal of increasing efficiency and reducing the backlog.

File Review did not achieve this objective. Despite substantial increases in IRB staffing, resources, and processing capacity that enabled the tribunal to more than double its annual finalizations, the asylum backlog increased dramatically from approximately 17,000 to nearly 300,000 claims.

The concerns raised by the policy – regarding legal authority, adjudicative independence, and security screening – cannot be justified. Accepting claims without questioning weakens the adjudicative process, limits the ability to detect fraud and misrepresentation, constrains the independence of decisionmakers and undermines coordination with security and program-integrity partners.

Asylum claims cannot be presumed to be true. Fabricated narratives and forged documents are a real and persistent risk. In-person questioning is the primary means to test the truthfulness of each claim. A policy that accepts claims without questioning exposes Canada to fraud and may encourage misuse of the system.

Hearings also play a central role in Canada’s security and program-integrity framework. By excusing itself from the requirement to conduct hearings, the IRB’s policy undermines this screening function and increases risk ex ante.

The policy may interfere with the fact-finding process and undermine the independence of adjudicators in ways that may be contrary to the law of administrative tribunals by fettering their discretion, delegating their statutory authority, and affecting an improper consultation on findings of fact.

In adopting the policy unilaterally through a Chairperson’s Instruction – which is limited to internal operations – the IRB may have exceeded its authority. This instrument of policymaking is not legally capable of displacing the tribunal’s core statutory obligation to adjudicate claims through hearings, nor may it undermine the intervention mandates of CBSA and IRCC. The File Review policy may therefore be ultra vires because the IRB lacks the unilateral authority to implement policies with system-wide effects.

For these reasons, the File Review policy should be brought to an end. All asylum claims should be adjudicated through in-person hearings without shortcuts. Board members should be just as supported and encouraged in their negative decisions as in their positive ones. The culture of the tribunal should not encourage one substantive legal outcome over another. Consistency is important, but with the presence of unfounded and fraudulent claims and Canada’s national security implicated, every claim warrants scrutiny.

Finally, the development and implementation of the File Review policy raises broader questions about whether Canada’s current model for asylum adjudication receives sufficient oversight. Administrative tribunals are creatures of statute, and their structure and accountability mechanisms are matters of legislative choice.64Ocean Port Hotel Ltd v British Columbia (General Manager, Liquor Control and Licensing Branch), [2001] 2 S.C.R. 781, 2001 SCC 52 at para 24. While Singh requires that asylum claimants receive an oral hearing, it does not prescribe the institutional form in which that hearing must occur. The current model is not the only option capable of complying with Singh and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Government of Canada did not develop or approve this policy. The cabinet-driven process of policy development would ordinarily act as a check against overreach and provide valuable oversight and input, but the IRB appears to have excused itself from that process, taking an expansive interpretation of its quasi-independence. This raises broader questions about the suitability of Canada’s current approach to asylum adjudication. While the IRB’s policy decisions have implications for many federal portfolios, as well as provinces and municipalities, the current model places the asylum system at such a distance from government that it was possible for the File Review policy to be developed and implemented quietly and unilaterally.

At present, the Government of Canada has few direct levers over the asylum system. The IRB is, in relative terms, disconnected from the rest of the government and opaque. It should be possible to have a tribunal that is sufficiently independent but housed within a structure that provides visibility and policy oversight. A more accountable model would be better suited to handle future shocks and uphold public confidence in the system.

The author extends gratitude to Jeremy Kronick, Alexandre Laurin, Parisa Mahboubi, Rosalie Wyonch, and several anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. James Yousif was Director of Policy at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (2008-2011) and a board member at the Refugee Protection Division of the IRB (2015-2018). The author retains responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

Appendix A

ATIP requests to the IRB with respect to the File Review policy were dated March 2, 2023. For the disclosure packages, please contact the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Communications and Access to Information Directorate, referencing the question numbers below. A brief summary of each request follows.

A-2022-02096

The application criteria for public servant adjudicators at the IRB following the replacement of GIC appointed board members at the RPD, and any subsequent amendments.

A-2022-02097

The performance management framework for public servant decisionmakers at the RPD from the time that they replaced GIC-appointed decisionmakers at the RPD.

A-2022-02100

The development, policy approval, implementation and subsequent modification of the File Review policy and the Country Lists.

A-2022-02101

The list of countries and sub-national groups published at the time the File Review policy was announced. The process for determining which countries and groups were to be listed, amendments to the Country List, and the decision to remove the Country List from public display. The legal and policymaking authority for the File Review policy.

A-2022-02102

Communications with other areas of government and stakeholders with respect to the development and implementation of the File Review policy.

A-2022-02103

The pilot projects that preceded the formalization of the File Review policy in January 2019.

A-2022-02104

Data on claims finalized without a hearing under the File Review policy, broken down by country, sub-national group, and claim type, distinguishing between the number of claims and the total number of persons affected.

Appendix B

References

Canada. Immigration and Refugee Board. 2019. Chairperson’s Instructions. January.

______________. 2025. Refugee Protection Claims. September.

______________. 2019. Instructions Governing the Streaming of Less Complex Claims at the Refugee Protection Division. February 1.

______________. 2019. Policy on National Documentation Packages in Refugee Determination Proceedings. June 5.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02096 (initial disclosure). Unpublished document, April 30.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02097 (initial disclosure). Unpublished document, May 21.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02096 (supplementary disclosure). Unpublished document, September 10.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02097 (supplementary disclosure). Unpublished document, September 10.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02100. Unpublished document, November 7.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02101. Unpublished document, November 7.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02102. Unpublished document, November 7.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02103. Unpublished document, November 7.

______________. 2024. Reply to Access to Information Request A-2022-02104. Unpublished document, November 7.

______________. 2025. Departmental Results Report 2024–25.

Canada. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2016. Evaluation of the In-Canada Asylum System Reforms. April.

______________. 2025. Strengthening Immigration and Stopping Fraud. Statement, March 3.

Canada. Public Safety Canada. 2021. About the Listing Process. June 25.

Canada. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. 2025. Population of the Federal Public Service by Department. October 29.

Canadian Immigration Lawyers Association. 2025. The State of Immigration Fraud in Canada: How Canada Can Strengthen Public Protections, Integrity, and Confidence in Its Immigration System. March.

Crawley, Heaven, and Jessica Hagen-Zanker. 2019. “Deciding Where to Go: Policies, People and Perceptions Shaping Destination Preferences.” International Migration 57(1): 20–35.

European Council on Refugees and Exiles. 2024. “Overview of the Main Changes since the Previous Report Update – Germany.” Asylum Information Database. June.

______________. 2024. “Overview of the Main Changes since the Previous Report Update – Sweden.” Asylum Information Database. April.

______________. 2024 “Overview of the Main Changes since the Previous Report Update – France.” Asylum Information Database. May.

Hatton, Timothy J. 2004. “Seeking Asylum in Europe.” Economic Policy 19(38): 5–62.

______________. 2009. “The Rise and Fall of Asylum: What Happened and Why?” The Economic Journal 119(535): F183–F213.

Havinga, Tetty, and Anita Böcker. 1999. “Country of Asylum by Choice or by Chance: Asylum-Seekers in Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 25(1): 43–61.

House of Commons Library. 2024. Asylum Statistics. Research Briefing. UK Parliament. December.

James, Poppy, and Lucy Mayblin. 2016. “Factors Influencing Asylum Destination Choice: A Review of the Evidence.” Working Paper No. 04/16.1, University of Sheffield.

Keogh, Gerard. 2013. “Modelling Asylum Migration Pull-Force Factors in the EU-15.” The Economic and Social Review 44(3): 371–99.

Neumayer, Eric. 2005. “Asylum Recognition Rates in Western Europe: Their Determinants, Variation and Lack of Convergence.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49(1): 43–66.

United Nations General Assembly. 1951. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. 189 UNTS 137.

Yeates, Neil. 2018. Report of the Independent Review of the Immigration and Refugee Board: A Systems Management Approach to Asylum. April 10.

Related Publications

- Intelligence Memos

- Research