Home / Publications / Research / Reinterpreting the Canada Health Act: The 2025 “Holland Letter” and What it Means for Healthcare in Canada

- Research

- |

Reinterpreting the Canada Health Act: The 2025 “Holland Letter” and What it Means for Healthcare in Canada

Summary:

| Citation | Katherine Fierlbeck. 2025. "Reinterpreting the Canada Health Act: The 2025 “Holland Letter” and What it Means for Healthcare in Canada." ###. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Reinterpreting the Canada Health Act: The 2025 “Holland Letter” and What it Means for Healthcare in Canada – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Reinterpreting the Canada Health Act: The 2025 “Holland Letter” and What it Means for Healthcare in Canada |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/reinterpreting-the-canada-health-act-the-2025-holland-interpretation-letter-and-what-it-means-for-healthcare-in-canada/ |

| Published Date: | May 27, 2025 |

| Accessed Date: | November 20, 2025 |

Outline

Outline

Related Topics

Press Release

Files

For all media inquiries, including requests for reports or interviews:

Reinterpreting the Canada Health Act: The 2025 “Holland Letter” and What it Means for Healthcare in Canada

- In January 2025, former health minister Mark Holland issued a new interpretation letter introducing the “CHA Services Policy,” which requires provinces to publicly insure medically necessary services delivered by non-physician professionals – particularly nurse practitioners – when those services are equivalent to those provided by physicians.

- The letter exacerbates a long-standing ambiguity dating back to the establishment of Medicare – Canada’s publicly funded healthcare system consisting of 13 provincial and territorial insurance plans. The Canada Health Act (CHA) requires provinces to cover all insured services, not all medically necessary care. Historically, provinces have been free to define “insured services” only as those provided by physicians enrolled in the public insurance system. This has allowed room for physicians to provide medically necessary care outside of the public system.

- How, then, should the interpretation letter be understood? If the CHA Services Policy applies to all “medically necessary services, whether provided by a physician or other healthcare professional providing physician-equivalent services,” then this is a radical and sweeping provision that would affect both physicians and other healthcare professionals working outside of the public system.

- If, on the other hand, the CHA Services Policy applies only to healthcare professionals already providing medically necessary services within the public system, then its narrow scope limits its impact on curbing the growth of two-tier healthcare. This reinterpretation also relies on compliance mechanisms under sections 18 and 19 of the CHA, which may not formally apply to non-physician care.

Introduction

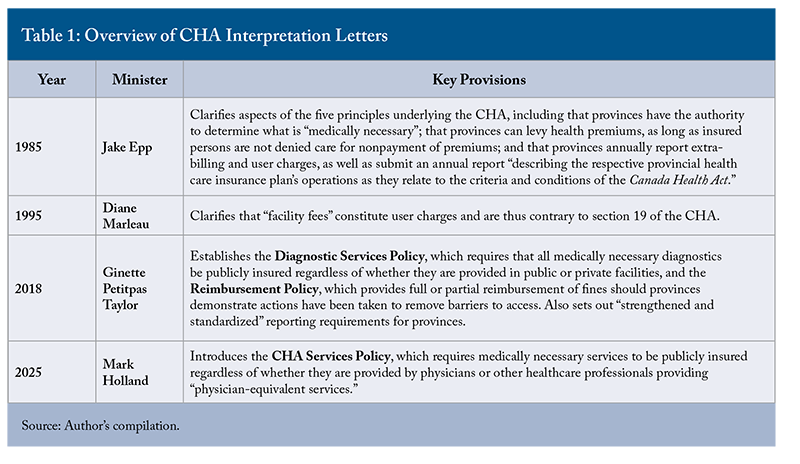

In January 2025, former federal health minister Mark Holland released a “Canada Health Act Interpretation Letter” outlining a new “CHA Services Policy.”1Holland, Mark. 2025. “Letter to Provinces and Territories on the Importance of Upholding the Canada Health Act – 2025.” Ottawa: Health Canada. January 10. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/canada-health-care-system-medicare/canada-health-act/letter-provinces-territories-january-2025.html. This marked the fourth “interpretation letter” issued with reference to the CHA. Notably, no other piece of legislation in Canada is connected to a formal “interpretation letter.” This Commentary examines the 2025 “Holland letter” within the context of previous interpretation letters.

The first section describes the form and function of successive CHA interpretation letters, while the second provides the historical context surrounding the various categories of public and private healthcare provision that prompted them. The subsequent sections analyze the content and intent of the 2025 Holland letter and assess how it departs from earlier interpretation letters – particularly in its treatment of key concepts. Notably, the letter addresses compliance using mandatory sanctions that are less applicable rather than discretionary ones that are more germane. Ultimately, the core issue the Holland letter raises is the tension between applicability and authority: in seeking to make the CHA adaptable to 21st-century healthcare, does this new interpretation move it too far away from the legislated scope of the statute? Conversely, if its scope remains more restricted, how effective will it be in restricting the expansion of private healthcare?

The CHA and its “Interpretation Letters”

What are “interpretation letters,” and what role do they play in Canadian healthcare? These letters are formal position statements issued by the federal minister of health to clarify the actions the minister expects provinces to take under the terms of the CHA, as well as the sanctions they may face for non-compliance. While interpretation letters carry no formal legal authority, they are significant because the CHA, as a federal statute, is binding only on the federal government. As such, these letters offer insight into how Ottawa interprets its responsibilities in administering and enforcing the CHA. Since interpretation letters are not legally binding, successive federal governments may revise their content. However, conflicting interpretations of legislation over time can undermine the force of the legislation and lead to considerable political frustration.

While the last three interpretation letters were issued by Liberal health ministers, the first was written by minister of health Jake Epp under the Conservative Mulroney government. The 1985 Epp letter was produced just a year after the passage of the CHA, and it addressed ambiguities in certain provisions of the Act – such as whether the principle of universality prohibited provinces from using healthcare premiums. The tone was respectful of provincial autonomy, and the process emphasized collaborative and consultative action based on goodwill and cooperative federalism.

All subsequent interpretation letters took a more focused approach, addressing specific issues related to healthcare provision. Ten years after the Epp letter, the 1995 Marleau letter raised concerns about “a trend toward divergent interpretations of the Act.” In particular, it addressed “the growth of a second tier of healthcare facilities providing medically necessary services that operate, totally or in large part, outside the publicly funded and publicly administered system.” These private clinics operated in a grey area, where patients could access publicly insured services only after paying an additional “facility fee.” Marleau categorized these payments as user fees, which were contrary to the accessibility provision of the CHA. The letter offered a reasoned justification for the federal position: first, while services once requiring a stay in a hospital can now be provided “outside of full-service hospitals,” the CHA was “clearly intended to ensure that Canadian residents receive all medically necessary care without financial or other barriers and regardless of venue.”

Importantly, the term “medically necessary” is not defined in the CHA itself. Rather, as the Epp letter explains, “provinces, along with medical professionals, have the prerogative and responsibility for interpreting what physician services are medically necessary.” On a more technical level, the CHA defines a hospital as “any facility which provides acute, rehabilitative or chronic care,” meaning such facilities cannot impose user fees. However, as the Epp letter also notes, “provinces determine which hospitals and hospital services are required to provide acute, rehabilitative or chronic care.” The tone of the Marleau letter was firm but cordial. Although it declared that facility fees violated section 19 of the CHA, the minister emphasized a continued commitment to a “consultative process” to resolve these violations.

The third interpretation letter, issued 23 years later, focused primarily on diagnostic services. The 2018 Petitpas Taylor letter introduced the “Diagnostic Services Policy,” which came into effect in April 2020. From that point on, provinces had to account for any medically necessary diagnostic services for which patients were paying out of pocket. This time, the sanction was clearly set out: beginning in March 2023, transfer payment deductions would apply to any private out-of-pocket payments for medically necessary diagnostic services, regardless of whether they were delivered by public or private providers.

The CHA explicitly notes that “laboratory, radiological and other diagnostic procedures” are part of the envelope of insured hospital services. And, while the definition of “hospitals” in the CHA only explicitly refers to facilities providing “acute, rehabilitative, or chronic care,” the CHA’s genesis as a statute incorporating the 1957 Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Care Act logically infers that medically necessary diagnostic services should be considered part of normal hospital care.

The compliance mechanism of the CHA is the federal government’s authority to impose financial penalties on provinces by withholding federal transfers made through the Canada Health Transfer (CHT).2In 2024-2025, the CHT amounted to over $52 billion compared to $36 billion in 2016-17. See: Department of Finance Canada. 2024. “Federal Support to Provinces and Territories.” Ottawa: Government of Canada. December 23. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/federal-transfers/major-federal-transfers.html. Because of the guaranteed escalators that are negotiated every few years, the CHT increases in absolute terms annually. The political issue is whether these increases meet the annual increases in healthcare expenditure (or whether they even should do so). In addition, Ottawa has negotiated bilateral health agreements with the provinces (one tranche was announced in 2017 and one in 2023). These agreements are targeted to enhance services that provinces and territories already provide to some degree, including home care, mental health, diagnostics, wait times, immunization, medical equipment, primary care access, and some pharmaceuticals. In March 2023, seven provinces were penalized a total of $76 million for violations of the Diagnostic Services Policy. But the Petitpas Taylor letter also introduced a Reimbursement Policy, allowing provinces showing any progress in addressing these violations to be reimbursed in part or in full. To access these reimbursements, provinces must provide:

- an account of the steps taken to meet the conditions required by the policy;

- a statement of any patient charges levied in the jurisdiction and how these charges have been addressed; and

- an attestation as to the completeness and accuracy of the information submitted.

By March 2024, British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec had received partial reimbursements for progress in addressing their diagnostic services policies. Finally, the Petitpas Taylor letter introduced “strengthened reporting requirements,” focusing on the standardization of information collected across jurisdictions.

The fourth CHA interpretation letter was released by former federal health minister Mark Holland. While the previous federal health minister, Jean-Yves Duclos, had made statements regarding the underlying position of the federal government on medically necessary non-physician services since early 2023, the formal Holland letter was issued in January 2025. The letter recognized that the scope of practice for many non-physician healthcare providers – particularly nurse practitioners – had expanded considerably to the point where they were delivering many of the same services as physicians.

But, as “insured services” were defined in the CHA as medically necessary services provided by physicians or in hospitals, a loophole had emerged. This allowed non-physician providers to offer “duplicate” services privately on an out-of-pocket basis, effectively creating a second tier of quicker access to private healthcare for those who could afford to pay. In practice, many provinces already insure some medically necessary services delivered by non-physician providers – such as pharmacist-administered vaccinations or nurse practitioner services in salaried, collaborative care clinics. The key issue raised by the letter is whether all of the services provided by non-physician healthcare professionals must be publicly insured if they are considered to be “medically necessary.”

To address this loophole, the Holland letter introduced the concept of “physician-equivalent services” that provinces are now expected to insure publicly. Under the CHA Services Policy, any medically necessary services provided by qualified non-physician professionals for private, out-of-pocket payment would be treated as “extra billing and user charges” under the CHA.3The CHA Services Policy states that “When the CHA Services Policy is implemented, patient charges for medically necessary services, whether provided by a physician or other healthcare professional providing physician-equivalent services, will be considered extra-billing and user charges under the CHA.” Provinces must begin reporting such patient charges under the new policy by December 2028, after which they may be subject to levies under section 20 of the CHA, which enforces penalties for violations of sections 18 and/or 19.

The reimbursement policy noted in the Petitpas Taylor letter would remain in effect under the CHA Services Policy: if a jurisdiction can show it is taking steps to address non-compliant practices, it may be eligible for retrospective reimbursement of any penalties imposed. The Holland letter also noted that Health Canada would be “monitoring” provincial policies on permitting private access to virtual or out-of-province healthcare services. Table 1 summarizes the provisions of all four CHA interpretation letters.

Is “Private Healthcare” Allowed Under the CHA or Not?

In 2005, Justice Deschamps declared, in her decision on the Chaoulli case, that “The Canada Health Act does not prohibit private healthcare services, nor does it provide benchmarks for the length of waiting times that might be regarded as consistent with the principles it lays down, and in particular with the principle of real accessibility” (para. 16).4Chaoulli v. Quebec (Attorney General), 2005 SCC 35 (CanLII), [2005] 1 SCR 791, https://canlii.ca/t/1kxrh.

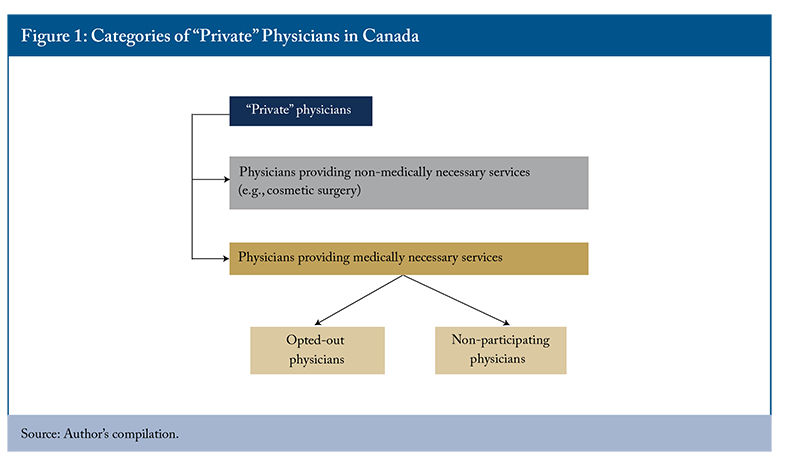

But what, exactly, is meant by “private healthcare”? If it simply refers to uninsured services provided by medical practitioners, then the statement is uncontroversial. For example, cosmetic surgery – typically paid for out of pocket – falls outside the scope of provincial legislation and is regulated solely by respective provincial colleges of physicians and surgeons.

Moreover, physicians providing insured services are also free to bill directly for uninsured services: in most provinces, this includes services such as wart removal or ear syringing. In general, if there is no billing code for a procedure and it is not restricted by the relevant provincial college, the treatment is considered to be uninsured, and physicians are free to bill patients directly. Problems only arise when “private healthcare” is interpreted to include the duplicate provision of “insured health services.” In such cases, the issue becomes considerably more complicated (Figure 1).

The conceptual problem is that the CHA is based on the principle of single-tier healthcare – yet, if physicians are legally permitted to provide medically necessary services privately, then a two-tier system clearly exists. Because of the historical contingencies described below, a legal space was carved out to permit physicians to make a living outside of the public insurance system. Legislatively, in most provinces, this space still exists, although it is configured differently in each province. Politically, however, provinces have imposed various constraints on private practice – such as limiting private fees to the public tariff, restricting reimbursement for patients who use private physicians, or limiting access to laboratory services and hospital privileges.

These measures made private practice unattractive to both patients and providers. The legal space for private physicians was, thus, for a long time, largely uninhabited. As a result, while two-tier healthcare existed in theory, single-tier healthcare prevailed in practice. But as the conditions surrounding the provision of healthcare changed, the economic viability of private practice began to shift as well, allowing the option of “two-tier” healthcare to gradually begin to manifest itself in practice as well as in law.5The explanation of how the healthcare landscape has changed over time and why this led to a burgeoning of private healthcare clinics is described in more detail in Fierlbeck (2024).

Saskatchewan formally began the path to universal public health insurance with the introduction of public hospital insurance in 1947. This was followed by Ottawa’s 1957 Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act as well as the 1966 Medicare Act, which together served as the basis for the 1984 Canada Health Act. Medicare provoked considerable pushback from many physicians when it was introduced in Saskatchewan in 1962. In response to the introduction of Medicare legislation, the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Saskatchewan staged a three-week strike.

In an attempt to placate the doctors and finalize the passage of the legislation, the province passed an order in council days before the strike that permitted physicians to practice outside the plan and allowed their patients to seek reimbursement from the provincial insurer at the existing payment tariff. As Marchildon (2024) documents, the resolution of the strike – known as the “Saskatoon Agreement” – established four payment options for physicians: (1) reimbursement through the provincial public insurer; (2) reimbursement through private insurers; (3) direct payment by patients, who could then request reimbursement from the provincial insurer; and (4) direct payment by patients without reimbursement. The dual categories of “enrolled” and “non-enrolled” physicians were thus established at the outset of Medicare.6The practice of “extra billing” can also be traced back to this point in time. As Marchildon explains, the ability for physicians in Saskatchewan to bill patients above the fee schedule was “neither prohibited nor set out as an explicit right” and was the result of the very specific way in which physician payments were calculated: “In the first payment option, doctors could participate directly in the plan by seeking reimbursement for patient fees, which were set at 85 per cent of the CPS [College of Physicians and Surgeons] fee schedule, since doctors no longer had to pursue patients for payment. In the second and third options, doctors could opt out of dealing with the government or the MCIC [public insurer] in any way, leaving this task to the patient. Both of these options offered doctors the possibility of extra-billing their patients by charging the full amount of the fee in the fee-for-service [FFS] schedule…” (Marchildon 2024, ch. 13).

While this contractual agreement was specific to Saskatchewan, the concessions offered to physicians were replicated with regional variations across other provinces as they respectively adopted Medicare within their own jurisdictions. The historical legacy of the Saskatoon Agreement has, in this way, informed the different ways in which “private” healthcare is seen as a legitimate practice in discrete provinces.

All provincial legislation – except Ontario’s – explicitly permits physicians the discretion to practice outside of the public health insurance system (i.e., to bill patients directly).7In Ontario, the 2004 Commitment to the Future of Medicare Act stipulated that physicians could only accept payment for insured services through OHIP. Unlike other provincial legislation, it states that a physician “shall not accept payment of benefit for an insured service rendered to an insured person” except from OHIP (10.3). Further, the Ontario Health Insurance Act defines “insured services” as those “prescribed medically necessary services rendered by physicians” (11.2[1]2). While “opted-out” or “non-participating” categories are not explicitly mentioned, it logically follows that if one is a physician providing medically necessary services, one is thereby providing “insured services” and can, therefore, only seek payment via OHIP. Physicians providing non-medically necessary care are free to seek direct reimbursement from patients in Ontario. By practising “outside” of the public health insurance system, the assumption is that physicians would be providing the same kinds of services as their colleagues within the public insurance system. At the same time, provisions are often set out in legislation stipulating the conditions under which this practice is acceptable in any specific province.

Given the historical and legislative context, “private healthcare” in almost all provinces (except Ontario) does, in fact, include all medically necessary services that regulatory colleges permit physicians to perform and for which patients pay directly out of pocket. And while this private stream has been present since the inception of Medicare, in most provinces, it has fallen largely into disuse because of the specific restrictions placed upon it, which has meant that there has not generally been a viable business case for this stream in the past.

How did the introduction of the CHA in 1984 affect this stream of private healthcare? The CHA was able to accommodate the practice of private healthcare with its commitment to single-tier, publicly insured healthcare by taking a dual approach. On the one hand, it declared that “all insured services must be publicly insured,” thereby ensuring universality for all insured persons. On the other hand, it gave provinces the authority to define “insured services” narrowly – for example, as only those medically necessary services provided by enrolled physicians or delivered in hospitals.

This allowed unenrolled physicians – and later, non-physician healthcare providers with expanded scopes of practice – to provide medically necessary services privately without violating the CHA. In other words, doctors could work outside the public system and still provide the full range of general practice (GP) services because non-enrolled physicians – by definition – did not provide insured services, and only insured services, according to the CHA, had to be publicly insured. What makes the 2025 interpretation letter notable, as discussed below, is that it would seem to call this private stream into question by redefining which services fall under the scope of the CHA.

Physician Streams: From “In or Out” to Participating, Opted-Out, and Non-Participating

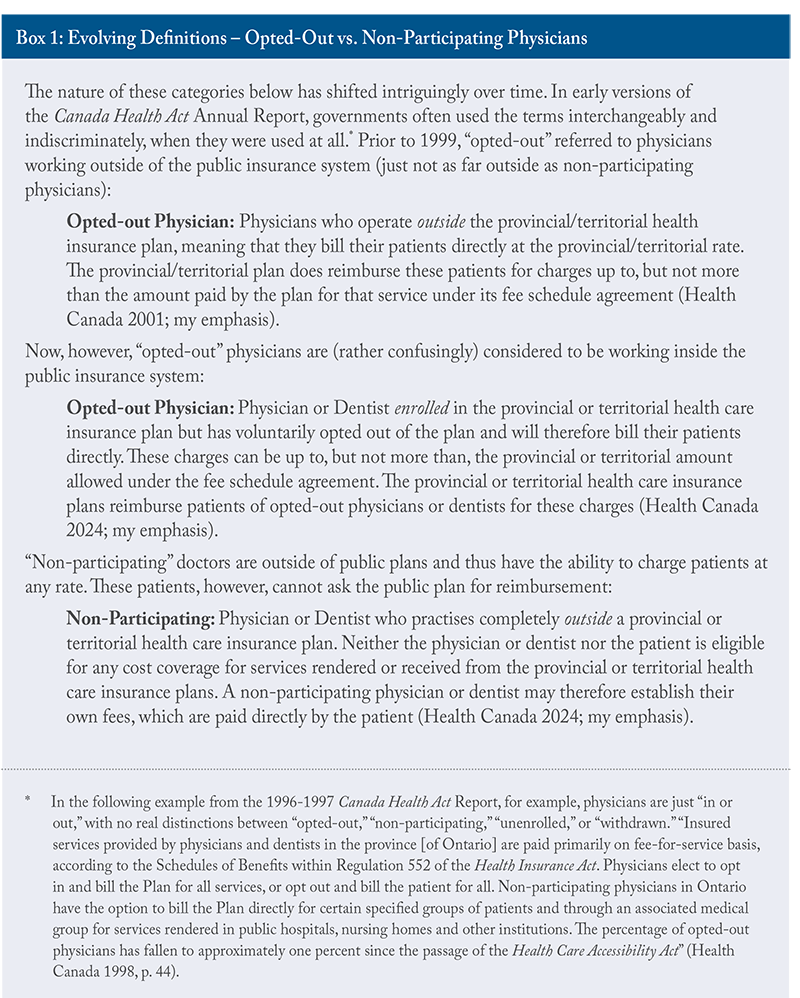

Rather than a simple division between “enrolled” and “non-enrolled” physicians, there are now two categories of “non-enrolled” physicians: “opted-out” and “non-participating,” in addition to the category of enrolled physicians.

Why did these categories of physicians evolve over time, and why did the nomenclature become more important? To answer this, it is useful to remember the policy context of the late 1990s. One key concern noted by the federal health minister of the day, Diane Marleau, was a trend “toward divergent interpretations of the act” that was leading to an increase in the number of private clinics. In response, her 1995 letter clarified that facility fees constituted user charges and were thus contrary to section 19 of the CHA. Given this, penalties for non-compliance were non-discretionary. Marleau also exhorted provinces to “take whatever steps are required to regulate the development of private clinics in Canada.”

To this end, provinces increasingly began to enforce the provision that opted-out physicians wanting to charge patients directly could only do so up to the public fee schedule and no higher. This cap on what physicians could charge outside the public insurance system made private practice far less economically viable. After all, why would patients pay for what they could receive for free at the point of service? And why would a physician work in the private rather than public sector if their remuneration was the same one way or the other?

Nonetheless, it remained technically legal for physicians to work outside the public system, thereby preserving the understanding underlying the introduction of Medicare that physicians would not be forced to work in a public system.8The rhetoric surrounding the introduction of Medicare in Saskatchewan was not subtle: the Liberal leader, Ross Thatcher, stated that the Medicare bill was no less than “the conscription of the medical profession” designed to “put doctors into slave camps” (Marchildon 2024, ch. 12). In practice, fee caps became an effective means of limiting private GP clinics while preserving the category of “working outside the public system.” Currently, all provinces with a private stream allowing for public reimbursements have fee caps. By contrast, Alberta, New Brunswick, and Ontario prohibit public reimbursement for any private medically necessary services and thus do not apply fee caps.

But this “lid” on fees that physicians could charge was seen by some physicians as reneging on the bargain that was struck when Medicare was introduced to protect physician autonomy, which some physicians still understood as being able to work independently and be able to make a living doing so. Some provinces adopted an “all-out” (non-participating) category as a means of addressing these concerns. Following the Quebec doctors’ strike of the 1970s, for example, the categories of both “opted-out” (direct payment by patients of a capped fee that can be publicly reimbursed) and “non-participating” (direct payment by patients of an uncapped fee, without the possibility of public reimbursement) were clearly presented (Marchildon 2024). Provincial legislation in some provinces goes even further, clearly stating the right of physicians to work outside the public insurance system.9In New Brunswick, for example, section 3(b)iv of the Medical Services Payment Act sets out the right of a medical practitioner “to elect in accordance with the regulations to practice his profession outside the provisions of this Act and the regulations.”

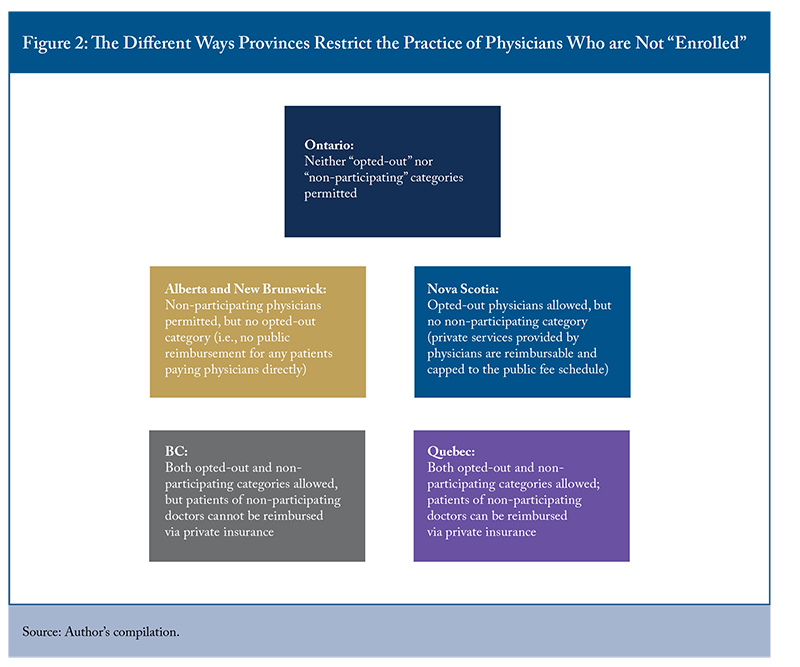

Provinces vary considerably in the way in which they understand these two separate categories of physicians working outside of the public insurance system. Provinces have regulatory authority to determine the conditions under which physicians are permitted to work outside the public system, and the specified conditions reflect the particular relationships between provincial governments and physicians’ associations over time (Figure 2).

Ontario has the most restrictive provisions, allowing neither opted-out nor non-participating categories. Physicians can work “privately” only if they provide services the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) does not cover. New Brunswick and Alberta allow doctors to bill privately for services that are also covered publicly but will not reimburse patients for medically necessary services provided by any physicians charging patients directly (in other words, they technically have a category of “non-participating” physician but do not have that of “opted-out.”)10The nomenclature used by provinces differs; ignoring the terminology and focusing on the regulatory restrictions provides a clearer picture (Fierlbeck 2024).

Nova Scotia, conversely, sanctions the category of “opted-out” but not of “non-participating.” While non-participating physicians in British Columbia can set their own fees, they must be paid directly out of pocket by patients (rather than through private insurance). Quebec reimburses fees for patients of opted-out doctors (up to the public tariff) and also permits non-participating doctors to charge whatever they want. Unlike British Columbia, Quebec allows non-participating doctors to be paid via private insurance.

In sum, the “Saskatoon Agreement” between physicians and provinces was the understanding that carved out a separate “private” system of healthcare in Canada in 1962, along with a system of public health insurance. But, throughout the 1970s, “physician extra-billing intensified to the point that it became a serious impediment to patient access in some provinces” (Marchildon 2016, p. 677), leading to the establishment of the CHA as a bulwark for public health insurance. As noted, the restrictions on how and where physicians could practice “privately” were successful enough to restrict the number of physicians working outside Medicare.

But the context of healthcare has continued to evolve throughout the 21st century. More allied healthcare professions have emerged, scopes of practice have widened, and access to doctors has become seriously curtailed. All of this means that the structure of incentives has shifted considerably: those patients who cannot access timely services will be more willing to pay for services that, in theory, they could receive free at the point of access if they could find them; and physicians increasingly have sufficiently large pools of clients to support private practice. Thus, Canada has once again found itself with a burgeoning two-tier system of healthcare. And this has led to the current line in the sand.

The Holland Letter and Its Consequences

In January 2025, former federal minister of health Mark Holland formally issued a new interpretation letter, which introduced the “CHA Services Policy.” When this policy comes into effect in April 2026, “patient charges for medically necessary services, whether provided by a physician or other healthcare professional providing physician-equivalent services, will be considered extra-billing and user charges under the CHA.” This would seem to cleave closely to section 9 of the CHA, which expects services to be “comprehensive.”

In other words, if a province deems a service to be medically necessary and decides to insure it, Health Canada expects all eligible people in the province to be able to receive that service free at the point of delivery – regardless of who provides it or where it is provided. The reasoning is that, as the mode of healthcare delivery has evolved, so too must the application of the CHA. If medically necessary diagnostic care is now provided in private clinics rather than hospitals, they must be publicly insured. Likewise, if such services are now provided by nurse practitioners or pharmacists, they must, in a similar manner, be covered.

As noted above, provinces differ considerably regarding those who are allowed to provide “medically necessary” care and how they can be remunerated. With the passage of the 2004 Commitment to the Future of Medicare Act, Ontario went furthest in ensuring that medically necessary services were only available under the aegis of public insurance. In other provinces, specific conditions for private practice diminished its viability. But as the provision of medically necessary care has expanded beyond physicians and hospitals, and as demand for healthcare services has risen, these measures have been increasingly unable to constrain private access to care. The CHA Services Policy, therefore, is an attempt to address these new patterns of provision within the existing structure of the CHA.

Ottawa has used interpretation letters to allow the administration of the CHA to evolve in step with the healthcare system. At its heart, the objective of the CHA is to ensure that patients should not face charges for access to medically necessary services which would normally be covered by a physician. But this new policy is problematic on at least two fronts: first, it moves away from the definition of “insured services” clearly set out in the CHA, raising the question of whether the interpretation letter is making a substantive change to the legislation itself; and second, the proposed compliance mechanisms are an awkward fit.

The CHA formally defines insured services as “hospital services, physician services and surgical-dental services provided to insured persons.” Physician services, in turn, are “any medically required services rendered by medical practitioners,” and medical practitioner “means a person lawfully entitled to practise medicine in the place in which the practice is carried on by that person.” Unless the term “medical practitioners” is expanded to include all regulated healthcare providers (a measure that physicians’ organizations will doubtless resist fiercely), the CHA clearly limits the formal understanding of insured services to those provided by physicians (or dental surgeons) or in hospitals.

This specificity is reinforced by the 1985 Epp interpretation letter, which states that “Services rendered by other healthcare practitioners, except those required to provide necessary hospital services, are not subject to the Act’s criteria.” Yet the Holland letter, in insisting that Canadians should not face charges for medically necessary services normally covered by a physician, implicitly insists that the key definitional feature of “insured services” is simply that they are medically necessary, regardless of who provides them.

If the Holland letter reinterprets the provision in section 9 of the CHA that “insured services ought to be publicly insured” to mean that all medically necessary services ought to be publicly insured, this is a remarkably radical position. Again, the complexity that arises here is that the CHA does not itself define “medically necessary.” Instead, that determination is left to the provinces, which retain the authority to define the term as they see fit. Yet, in practice, no province explicitly defines “medically necessary” in legislation. Rather, provinces use terms such as “insured services,” “basic health services,” or “authorized benefits,” typically defined as medically necessary services delivered to eligible residents by authorized providers.

So how do provinces determine which services are “medically necessary”? Generally, these are the services that each province, in negotiation with its medical association, agrees to insure. Outside of hospital care, these are typically the services for which billing numbers exist. This is why the wording of the CHA could be understood as implicitly recognizing the traditional carve-out for physicians who chose not to work within the public system. These doctors could provide “medically necessary” services outside the public system because the CHA required public coverage only for “insured services” – a term defined by each province, typically as medically necessary services delivered by enrolled physicians.

Not only does the CHA Services Policy challenge the formal definitions set out in the Act – and confirmed in a previous interpretation letter – but it would also seem to create a logical inconsistency in creating what it terms “physician equivalent services.” Under the original terms of the CHA, non-physician healthcare providers were, like non-participating physicians, clearly exempt from the CHA. But, as non-physicians increasingly provide medically necessary services, the policy now classifies their work as “physician-equivalent” and brings it under the CHA’s jurisdiction.

This raises the question of why one group of care providers – non-physicians – should be brought under the aegis of the CHA while another group – non-participating physicians – remains outside it. Presumably, if the reason to bring non-physicians within the ambit of the CHA was that patients should have access to medically necessary services based on need rather than the ability to pay, the same would hold true for non-participating physicians. Politics aside, there is no clear reason for insisting the former group should now be subject to the CHA, but the second group should not.11Interestingly, in defining the CHA Services Policy, the Holland letter refers only to “physicians” rather than “enrolled physicians” (“when the CHA Services Policy is implemented, patient charges for medically necessary services, whether provided by a physician or other healthcare professional providing physician-equivalent services, will be considered extra-billing and user charges under the CHA.”) The policy also does not include regulated health providers who had an overlapping scope of practice with physicians prior to the enactment of the CHA in 1984 and whose services were not considered insured at that time (e.g., optometrists, podiatrists, psychologists).

In fact, the reach of the new CHA Services Policy is far more restrictive than it might seem, given the emphasis on “medically necessary care.” Although non-participating physicians may provide “medically necessary care,” they are not bound by the CHA as they are “completely outside” of the CHA. That has not changed. Similarly, non-physician healthcare workers – such as nurse practitioners – who provide medically necessary services entirely outside of the CHA are not subject to the CHA Services Policy; thus, private clinics that are staffed by nurse practitioners will not be affected by the CHA Services Policy.

The policy would, however, address nurse practitioners working in both public and private sectors (e.g., a practitioner who works in a public clinic during the week and takes occasional shifts at a private clinic on the weekend). As such, this more restricted scope for the Holland letter does remove a number of potentially contentious political issues: it would not, for example, oblige Quebec to publicly cover the services provided by over 800 non-participating doctors in the province, nor would it require any province to cover the costs of medically necessary services provided by nurse practitioners working in private clinics if they are working completely outside of the CHA. However, if this is the case, then these kinds of private options will continue to operate within the legitimate parameters of each province. Depending on the demand for these services and the nature of provincial legislation, the Holland letter will have little impact on the growth of private healthcare.

Another issue with the Holland letter is the compliance mechanism. The rationale for the new CHA Services Policy, again, is to ensure that medically necessary services should be accessible based on need rather than ability to pay. This, of course, is in keeping with the overall philosophy of Medicare. But if the relevant point is to protect the overarching principle of Medicare, then the most appropriate compliance approach would be to argue that provinces are not meeting the five key principles of the CHA (sections 8 to 12).

This would seem to be especially apropos for section 9, which not only insists on all insured services provided by physicians and hospitals being insured but also, “where the law of the province so permits, similar or additional services rendered by other healthcare practitioners.” Section 15 gives the federal government the authority to levy penalties for perceived violations of the five principles of Medicare outlined in sections 8 to 12. Section 15, then, would appear to be the most appropriate mechanism for ensuring compliance vis-à-vis the CHA Services Policy.

But the minister has stated that penalties for allowing non-physician healthcare workers to provide medically necessary services will be levied under sections 18 and 19, which refer to extra-billing and user charges. This is not a comfortable fit. The CHA explicitly defines “extra-billing” as billing for services rendered to an insured person by a medical practitioner, so any nurse practitioner or pharmacist services, by definition, would not seem to fall under section 18.12Sections 18 and 19 are also being used to levy penalties under the Diagnostic Services Act. While medically necessary diagnostics at a private clinic are not formally “hospital services” (as they are not provided at a hospital), they could fall under “services provided by a medical practitioner” if tests are performed or interpreted by physicians rather than technicians.

Similarly, these services are not technically “user charges,” which are defined by the CHA as “charges for an insured service that is permitted by a provincial plan that is not payable by that plan.” But if “insured services” are, by definition, only provided by enrolled physicians, then section 19 does not apply to either non-physicians or non-participating physicians as they do not, according to definitions set out in the CHA or by Health Canada, provide insured services.

This having been said, there are arguably reasonable grounds to use sections 18 and 19 as compliance mechanisms. The use of sections 14 and 15 (discretionary penalties) requires intensive consultation with provincial officials, and if there is no resolution, a decision must be made by the federal cabinet regarding what an appropriate penalty would be. The use of section 20 (mandatory penalties), in contrast, can be addressed by the federal minister of health alone. Perhaps more importantly, any penalties levied under section 20 are eligible for reimbursement; those levied under section 15 are not.

What Follows from this Reinterpretation of the CHA?

If the Holland letter is interpreted widely, then it will have a considerable impact on the provision of private care but will also generate more acrimonious political relationships. If interpreted narrowly, it will likely have much more provincial support but will also have much less effect on the growth of private healthcare services.

If “insured services” are now understood to be medically necessary services, regardless of who provides them, then a unilateral and quite significant change to the definition of the statute has been made via an interpretation letter.13That the CHA should cover “all medically necessary services” rather than simply “all insured services” regardless of the wording of the legislation is a position that Health Canada has articulated elsewhere as well. “The Canada Health Act requires provincial and territorial health insurance plans to cover ‘all medically necessary services,’” Health Canada spokesperson Anne Génier said in a statement. See: Hauen, Jack. 2023. “Snubs and For-Profit Surgeries.” iPolitics. January 16. https://www.ipolitics.ca/2023/01/16/snubs-and-for-profit-surgeries/. Note here that Health Canada is not saying that all “insured services” should be publicly insured (which is what the CHA stipulates) but rather that all medically necessary services should be insured. As noted above, substantive revisions to legislation must be executed through legislative amendment, and it is arguable that the redefinition of key terms is a substantive change. It is also a change made during a period of prorogation, and thus without the involvement of Parliament.

Not only does the CHA itself define “insured services” quite specifically as medically necessary services provided by physicians or in hospitals, but the 1985 Epp interpretation letter, as noted above, also clearly reiterates that “insured services” are only those provided by physicians. This is further reinforced by the 2004 Auton case, in which the Supreme Court of Canada held that the CHA’s “only promise is to provide full funding for core services, defined as physician-delivered services.”14Auton (Guardian ad litem of) v. British Columbia (Attorney General), 2004 SCC 78 (CanLII), [2004] 3 SCR 657, at para. 43 https://canlii.ca/t/1j5fs.

Provinces until recently had full discretion over how they defined “insured services,” and, in line with the definitions set out in the CHA, they have generally defined “insured services” not as a set basket of specific services but rather as medically necessary services provided by physicians (or dental surgeons) or in hospitals. Under the broader interpretation of the letter, if provinces insure specific services – essentially if they provide billing numbers for these services – then those services must be publicly insured regardless of who provides them or where they are provided. This would close the loophole that allows allied health professionals to offer “insured” services out of pocket and eliminate the model that many private medical and diagnostic clinics have been using to provide services privately.15It would, of course, be theoretically possible for these clinics to establish contracts with the public sector to continue to provide services, but (especially in the case of diagnostic clinics using expensive equipment) a business may decide that it cannot remain viable with the amounts set out in the public tariff for which it might be eligible if it were to establish contracts with provincial insurers. They could also still be able to treat uninsured individuals privately. Regardless of how “insured services” are defined, individuals who are not insured are not eligible to receive them. This category includes those whose care is covered by workers’ compensation, those in the Canadian Armed Forces, new permanent residents, or out-of-province patients. The question is whether there are sufficient numbers of people in these categories to provide a viable income for physicians who want to work outside the public system.

Moreover, if insured health services are no longer defined on the basis of who provides them (or where they are provided) but rather according to whether they are medically necessary, then the question arises of what becomes of the category of “non-participating” physicians. If any medically necessary care provided by a physician must be publicly insured, then non-participating doctors cannot be paid privately for these services. The Holland letter only explicitly addresses non-physicians providing the same services as the publicly insured services provided by GPs. But again, if the rationale for this is to ensure that patients have access to medically necessary care on the basis of need rather than access, the same reasoning should similarly apply to non-participating physicians.

Provinces are not obliged to recognize non-participating physicians (some already do not). Ottawa could, in theory, insist on this, although this could involve considerable political costs. Given the wording of the CHA, not only may the provinces hold that this reinterpretation is rather tenuous, but they are also quite aware that they will be liable for the additional costs incurred in moving these services to the public sector and may argue that this is simply another instance of federal cost-shifting, with provinces being expected to bankroll federal political objectives. (In the usual rhetorical exchange of salvos, Ottawa would likely counter that the considerable funds provided through recent bilateral agreements, as well as increased CHT payments, should be sufficient to support this expansion of services).

If the Holland letter is interpreted more narrowly, then it will be both far less contentious and much less effective in restricting access to private healthcare. Still, it will place greater limitations on provinces’ ability to define “insured services” – a term which rests at the heart of provincial health insurance statutes. The CHA’s definition of “insured health services” (“hospital services, physician services, and surgical-dental services provided to insured persons”) clearly allows provinces the discretion to decide which services to insure, which explains why insured services vary across provinces.

On the one hand, this still permits provinces to define the basket of services that they choose to insure. If they choose not to insure wart or ear wax removal, then wart or ear wax removal remains uninsured, even if other provinces were to consider these services to be “medically necessary.” In this sense, provincial authority to define insured services remains. On the other hand, it limits provinces’ broader authority to define insured services – not just in terms of the services themselves, but also with respect to who provides them, where they are delivered, and how they are administered – an area of discretion provinces have historically exercised.

A secondary issue focuses solely on federal politics. One question that arose in this analysis is why the federal health minister chose to use sections 18 and 19 rather than section 9 as a basis for the CHA Services Policy. Two explanations offered earlier were that sections 18 and 19 are addressed at the ministerial rather than cabinet level and that reimbursements are only available for section 18 and 19 violations. Another possible explanation is that the government is using sections 18 and 19 – rather than section 9 – as compliance mechanisms precisely because they are mandatory, whereas section 9 is not. In doing so, this new interpretation of the CHA may serve to constrain the ability of future governments to reverse or weaken the policy.

Ottawa is technically bound to obey its own statutes regardless of who is in power; it could conceivably face a writ of mandamus should it not do so. But if that is the case, then why not simply revise section 15 to make enforcement of section 9 mandatory rather than discretionary? It is a federal statute; the federal government can amend it any way it wants without any provincial input. The problem is likely that making section 9 mandatory could conceivably open too large a can of worms, as it could force Ottawa to act far more aggressively than it wanted (especially under a regime that did not strongly support the CHA). This scenario, in turn, could lead such a government to rescind the CHA altogether.

Conclusion

The Holland interpretation letter is a “line in the sand” separating those wanting to restrict two-tier healthcare in a changing world and those holding that the spirit of the Saskatoon Agreement must be respected. This tension has, of course, existed in some form since 1962. In attempting to make the CHA more responsive to the principle that “Canadians should be able to access medically necessary care based on need rather than the ability to pay” within the current healthcare context, the new interpretation letter straddles a difficult tension.

On the one hand, if its scope is cast wide, then it raises contentious political questions – such as who has the substantive authority to define “insured services” and what the costs to provinces will be in shifting these services from the private to the public sector. On the other hand, if the new CHA Services Policy only applies in a much more restricted manner – excluding non-enrolled physicians and non-physician healthcare providers delivering medically necessary services entirely outside the public system – then the underlying issue remains unresolved: the continued growth of privately delivered healthcare services within this parallel sector continues unchecked.

The interpretation letters associated with the CHA were meant to adapt the CHA to changes in the way in which healthcare is provided now. Specifically, they attempt to ensure that Canadians continue to have access to medically necessary care on the basis of need rather than ability to pay. But as the healthcare landscape keeps shifting over time, the question arises as to how much work the interpretation letters can themselves do and the extent to which the CHA itself needs to be formally amended (or even replaced) to perform the functions expected of it. As always with public healthcare, this ultimately becomes a matter of political will rather than legal or administrative interpretation. It also highlights the larger issue of access to healthcare services more widely: the more difficult it is for Canadians to find publicly insured healthcare in a timely manner, the less support they will have for provisions that limit access to care outside of the public sector.

Conversely, the more secure people are in their ability to access healthcare services in a timely manner, the more willing they will be to uphold restrictions on private care for everyone. In other words, the force of the CHA is secondary to how effective the public systems are in meeting needs, and this, in turn, is largely a matter of political will for the provinces as well as – and perhaps even more so than – the federal government. Until or unless the issue of demand is effectively addressed, attempts to reposition the CHA through interpretation letters will continue to be a game of “whack-a-mole” where public demand generates an increasing array of options outside the public system for those who are willing to pay to access them.

The author extends gratitude to David Walker, Joan Weir, Rosalie Wyonch, Trisha Hutzel, William B.P. Robson, Tingting Zhang and several anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. The author retains responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

References

Fierlbeck, Katherine. 2024. The Scope and Nature of Private Healthcare in Canada. Commentary 651. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. January. https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/scope-and-nature-private-healthcare-canada.

Health Canada. 1998. Canada Health Act Annual Report 1996–97. Ottawa: Government of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H1-4-1997E.pdf.

____________. 2001. Canada Health Act Annual Report 1999–2000. Ottawa: Government of Canada. https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/ar_canada_health_act/H1-4-2000E.pdf.

____________. 2024. Canada Health Act Annual Report 2022–2023. Ottawa: Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/health-system-services/canada-health-act-annual-report-2022-2023.html.

Laverdière, Marco. 2025. “Mark Holland’s New Interpretation of the Canada Health Act: Too Little Too Late?” Policy Options. January 31. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/january-2025/canada-health-act-interpretation/

Marchildon, Gregory. 2016. “Legacy of the Doctors’ Strike and the Saskatoon Agreement.” CMAJ 188 (9): 676–677.

Marchildon, Gregory. 2024. Tommy Douglas and the Quest for Medicare in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.