Home / Publications / Research / Don’t Take It for Granted: Strengthening the Bank of Canada’s Independence

- Media Releases

- Research

- |

Don’t Take It for Granted: Strengthening the Bank of Canada’s Independence

Summary:

| Citation | Steve Ambler and Kronick, Jeremy and Koeppl, Thorsten. 2025. "Don’t Take It for Granted: Strengthening the Bank of Canada’s Independence." ###. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Don’t Take It for Granted: Strengthening the Bank of Canada’s Independence – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Don’t Take It for Granted: Strengthening the Bank of Canada’s Independence |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/dont-take-it-for-granted-strengthening-the-bank-of-canadas-independence/ |

| Published Date: | November 25, 2025 |

| Accessed Date: | November 25, 2025 |

Outline

Outline

Authors

Related Topics

Files

For all media inquiries, including requests for reports or interviews:

- In this E-Brief, we make the case for the importance of central bank operational independence from government.

We make two proposals to further strengthen the already well-entrenched independence of the Bank of Canada.

We make two proposals to further strengthen the already well-entrenched independence of the Bank of Canada. First, we argue for strengthening parliamentary oversight over the use of section 14 of the Bank of Canada Act, which allows the government to provide written direction on monetary policy to the governor.

First, we argue for strengthening parliamentary oversight over the use of section 14 of the Bank of Canada Act, which allows the government to provide written direction on monetary policy to the governor. Second, we argue there is a need to further formalize the principle that the Bank of Canada can rebuild capital and reserves after temporary losses before again remitting profits to the government. To that effect, we propose to clarify the scope of section 27 of the Bank of Canada Act.

Second, we argue there is a need to further formalize the principle that the Bank of Canada can rebuild capital and reserves after temporary losses before again remitting profits to the government. To that effect, we propose to clarify the scope of section 27 of the Bank of Canada Act.

Introduction: How Has Independence at the Bank of Canada Evolved?

The Bank of Canada was established as Canada’s central bank in 1934 under the Bank of Canada Act. Originally privately owned with shares sold to the public, the Bank became publicly owned and was designated a Crown corporation in 1938. The change in ownership reflected concerns the Bank would be influenced by outside interests.

The preamble of the Bank of Canada Act lays out the Bank’s mandate11 As in Williamson (2021), we will refer to the mandate as the preamble in the Bank of Canada Act, and the goals as those spelled out in the framework agreement between the Bank and federal government. in qualitative and general terms to allow for flexibility in interpretation.

The lack of precise quantitative goals in the Bank’s mandate has allowed the putative goals to evolve over the years, from defending a fixed exchange rate (from 1935 to 1950 and again from 1962 to 1970), to controlling money growth in order to fight inflation (from 1975 to 1982), to explicit inflation targeting starting in 1991. Since 1995, the Bank and the government of Canada have agreed on a quantitative goal of 2 percent inflation within a 1-3 percent inflation band to fulfill its mandate.2 2 For more details, see Powell (2005) and Thiessen (2000). They have renewed this agreement every five years since, and it is due again for renewal in 2026. We note that around the time that inflation targeting came into effect, there was a thought to make price stability the specific mandate of the Bank and insert it into the Bank of Canada Act. Ultimately, however, a tripartisan committee chaired by John Manley recommended against such a move.33 See Parliament of Canada (1992) and Desroches, Kozicki, and Simon (2024) for more.

The five-year renewal cycle has allowed the Bank to periodically investigate alternative monetary policy goals. Its research has repeatedly concluded that there is no compelling case to move away from the flexible inflation targeting framework, centred around a 2 percent inflation target.44 See, for example, Dorich et al. (2021).

When the Bank of Canada was established, the parliament of the day understood that the central bank needed to be free of political interference (Chant 2022). The principle of central bank independence has been largely maintained, despite some challenges. Examples include, most notably, the Coyne affair in the late 1950s/early 1960s (which we discuss below) and the period of fixed exchange rate with the US dollar in the 1960s – a policy the Bank supported, but effectively nullified its independent conduct of monetary policy.55 See Laidler and Robson (1994, 2004) for more.

The Bank’s independence today consists of its ability to decide how best to use its tools – most commonly the overnight rate target – to achieve 2 percent inflation. The key point is that by giving the Bank of Canada a quantitative goal consistent with its mandate and the ability to use policy instruments as it sees fit to achieve that goal, the government is allowing the Bank of Canada to have what we refer to as “operational” independence.66 Our terminology mirrors Debelle and Fischer’s (1994) work on goal versus instrument independence. “A central bank has goal independence when it is free to set the final goals of monetary policy. A bank that has instrument independence is free to choose the means by which it seeks to achieve its goals.” The Bank of Canada has instrument independence – what we refer to as operational independence – but not goal independence.

Lately, however, that operational independence has come under threat, in particular following the inflation surge post-COVID, which is seen to have damaged central bank credibility. Politicians in several countries, including Canada, have talked of firing the head of their respective central bank and wading into interest rate decisions. The situation has become notably hostile in the United States, where President Trump has attempted to fire the Chairman and some members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. As Binder (2021) shows, increased political pressure often has an impact on both inflation and inflation expectations.

In this E-Brief, we argue that the Bank of Canada’s operational independence cannot be taken for granted. While the Bank of Canada is ultimately accountable to Parliament and, more broadly, Canadians (see the Appendix for more on the Bank of Canada’s structure), we argue that in the current political climate, we should look for ways to strengthen the operational independence of the Bank of Canada. Below, in a question-and-answer format, we first review the importance of central bank independence, then assess to what degree the Bank of Canada is independent, before making concrete suggestions to further boost operational independence for the Bank.

Q: Do independent central banks deliver better performance?

A: Yes, independence leads to lower inflation and less volatile economic activity.

In the 1970s, inflation in many developed countries – including Canada – climbed into double digits. Academics and policymakers alike realized that governments often pressured their central banks to over-inflate economies to finance fiscal deficits and stimulate growth, particularly during election periods.77 Kydland and Prescott (1977), Nordhaus (1975), and Barro and Gordon (1983). These efforts created an inflation bias, contradicting central banks’ mandates of low and stable inflation.

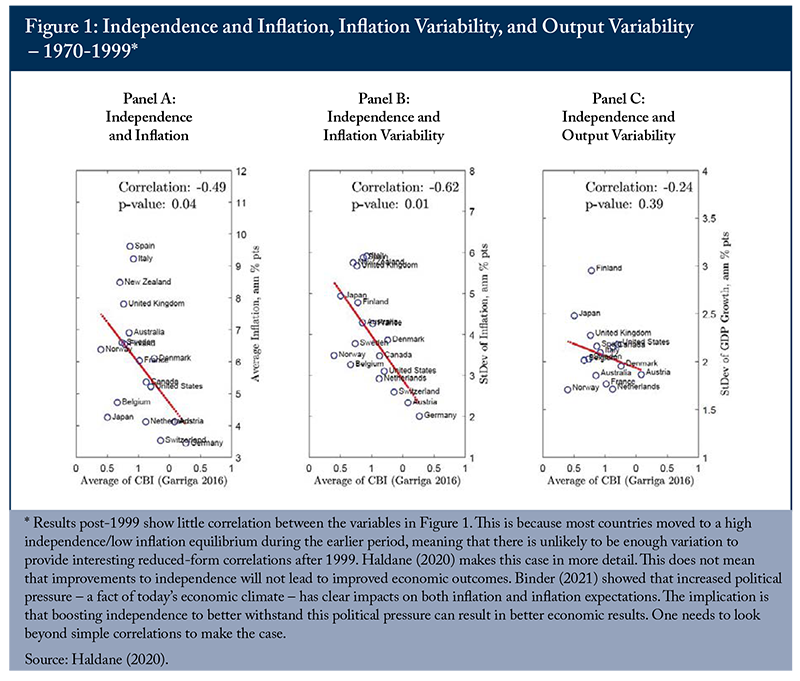

Cross-country evidence at that time established a significant negative correlation between central bank independence and both the level and variability of inflation (more independence leads to lower inflation/less volatile inflation).88 See Bade and Parkin (1988) and Alesina and Summers (1993), among others. It was this evidence that has led to central banks becoming increasingly operationally independent since the 1980s. More recent papers have confirmed these original findings. For example, Figure 1, taken from Haldane (2020), presents a sample of 18 countries (including Canada) that shows that more central bank independence not only delivers lower and more stable inflation, but also leads to more stable GDP.99 See also Bandaogo (2021), who references the work of Brumm (2002, 2011), Garriga and Rodriquez (2020), Berger, De Haan and Eijffinger (2001), and Klomp and De Haan (2010).

Q: How independent is the Bank of Canada?

A: Quite independent, but less independent than some other central banks.

The academic literature uses several different metrics when creating rankings for central bank independence. The metrics used usually distinguish between de jure and de facto independence, which respectively refer to formal independence as established in legislation (de jure) and to operational independence as demonstrated by actual policy process and central bank operations (de facto).

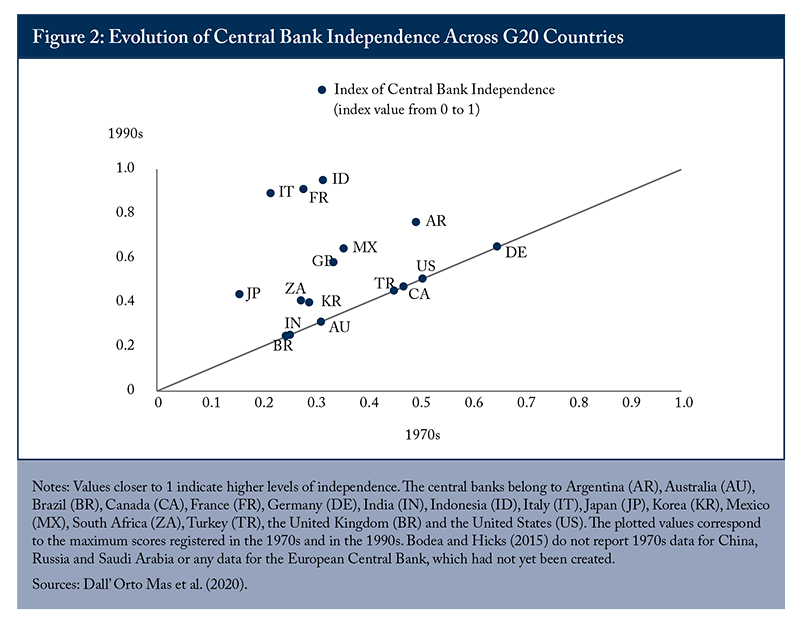

Figure 2, taken from Dall’Orto Mas et al. (2020), documents a big increase in de jure independence for several central banks from the 1970s to the 1990s. Canada is an interesting case in that the Bank of Canada’s quantitative score has not changed over time, but its ranking among other central banks has. The Bank was among the most independent central banks in the 1970s but declined to the middle of the pack by the 1990s, as others, most notably central banks in countries of the European Monetary Union, became increasingly independent. The Bank of Canada’s ranking is confirmed in other studies, such as Garriga (2016).1010 One main reason for its middle-of-the-pack ranking is that it can lend directly to the government. In reality, however, this is a weak concern. The Bank has not provided a formal direct advance to the government since 1935, the first and only year it happened (Chant 2022). The Bank does purchase government debt at auction in primary markets, making the distinction with a formal advance somewhat overstated. However, the vast majority of these purchases have been made to offset currency in circulation and to smooth financial markets.

A classic criticism of de jure measures points out that what is legally true might not capture what happens in practice. As a result, despite their own shortcomings,1111 To cite just one example, central bank governor turnover rate is a popular measure used in de facto independence measures: see, for example, Cukierman et al. (1992) and Sturm and De Haan (2001). But if the central bank head is subservient to the government, infrequent replacement does not signal independence. de facto measures of central bank independence have grown in popularity. Alpanda and Honig (2010) look at how much monetary policy deviates from expectations during “political monetary cycles” that capture electoral and fiscal budget cycles. More independent central banks would see less variation during these cycles. Using regressions, the authors rank the independence scores of different central banks. According to this metric, Canada is still towards the middle, but closer to the top than under the de jure measures.

Our interpretation of these results is that the Bank of Canada is strongly independent, though its independence could be strengthened still further. Identifying these opportunities is a worthwhile endeavour given the importance of operational independence for economic outcomes and current threats to it.

Q: What could compromise operational independence for the Bank of Canada?

A: Among others, increased demands on the central bank from government to pursue other goals than monetary and financial stability.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the Bank of Canada has faced calls to broaden its goals beyond monetary stability. While it is widely accepted that financial sector stability goes hand-in-hand with monetary stability, adding other objectives, such as supporting the transition to a greener economy or addressing inequality, mixes fiscal or political goals with the Bank’s goal of delivering 2 percent inflation. The latest renewal agreement between the government and central bank in 2021 replaced the traditional, short statement reaffirming the 2 percent inflation target with a much longer one that contained some passages suggesting other objectives, including a focus on supporting maximum employment.1212 Department of Finance Canada. 2021. “Joint Statement of the Government of Canada and the Bank of Canada on the Renewal of the Monetary Policy Framework.” Government of Canada. December 13. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2021/12/joint-statement-of-the-government-of-canada-and-the-bank-of-canada-on-the-renewal-of-the-monetary-policy-framework.html. Ultimately, the 2 percent inflation target was left in place, but the change in tone of the agreement was notable.1313 See Ragan (2021) for more.

This kind of “mission creep,” where a central bank is assigned additional tasks that are better addressed through fiscal and structural policy instruments, is a problem.1414 Murray (2021) lays out a set of guiding principles for thinking through such concerns; he concludes that there are serious flaws in a central bank being charged with such additional goals. We discuss this further in other work discussing the Bank’s flexible inflation targeting framework versus a dual mandate (see Ambler, Koeppl, and Kronick 2025). Once the Bank of Canada is more or less formally charged with achieving such goals, there will be political pressure to achieve them. The Bank does not have the proper tools to achieve these goals,1515 With one main instrument at its disposal, the Bank will not necessarily be able to achieve multiple targets, as Nobel Laureate Jan Tinbergen (1952) pointed out many years ago. putting its credibility at risk. Moreover, at some point, it may also be the case that the Bank will have to compromise between conflicting goals, thus losing its credibility to achieve its inflation target.

As a second risk, consider both how the Bank finances itself and the role unconventional monetary policy has played lately. The Bank is typically financially self-sufficient as it can fund its operations through the interest income it earns on the bonds it holds on its balance sheet.1616 As Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers (2022) put it, “Our expenditures are funded through our own operations rather than an appropriation from the government.” However, as the Bank started tightening monetary policy in 2022 in response to inflation, the interest paid on short-term settlement balances, which had increased significantly as a result of quantitative easing (QE), started to grow.1717 For more on QE, see the appendix in Ambler, Koeppl, and Kronick (2022). QE is a policy in which the Bank buys government bonds from financial institutions to lower long-term interest rates and stimulate borrowing and spending. In early 2023, the interest it paid on settlement balances began exceeding the interest it earned on the bonds on its balance sheet, leading to operational losses for the Bank.

This continues today and, consequently, the Bank of Canada does not have any profits to remit to the federal government. As Hall and Reis (2015) have pointed out, potential losses from QE leading to a negative equity position – as is the case for the Bank today – can raise the spectre of direct government intervention in monetary policy decisions. While a central bank can operate independently with a negative equity position, once the position is significant and sustained, it will ultimately affect its ability to finance its operations.1818 Benigno and Nistico (2020) argue that the intertemporal budget constraint of the central bank imposes an economic limit to the amount of negative equity that the central bank can have. In Canada’s case, being dependent on direct financing through the federal government could subject the Bank of Canada to political pressure to pursue other goals and challenge its operational independence in achieving price stability.

A third and final risk to central bank independence is that the federal government is under pressure to increase fiscal spending in many areas, such as defence, infrastructure, and structural change to increase productivity. Without judging the value of further fiscal expansion, the need for such initiatives is likely to require more government spending and higher government debt, which might raise the desire to monetize at least part of it.1919 Recent economic thinking has treated inflation as a fiscal phenomenon where higher debt necessarily implies (at least temporary) inflation (see Cochrane 2023). It might also cause the government of the day to lean more heavily on the central bank. Future coordination and consistency between fiscal and monetary policy is not guaranteed. Therefore, it may be helpful to look for ways to strengthen the independence of the Bank of Canada pre-emptively before such a scenario arises.2020 See Kronick and Petersen (2022) on how fiscal and monetary policy conflict can play out in practice. An example is as follows. Fiscal policy causes inflation to rise above target; the Bank of Canada is forced to tighten, but this increases debt costs. If fiscal policy becomes unanchored, governments need to go into increased deficits to maintain similar levels of government spending, leading to more inflation, and so on.

Q: What steps need to be taken to further strengthen the independence of the Bank of Canada?

A: Potential amendments to the Bank of Canada Act around the government directive and the remittance of profits.

The first concern around operational independence lies with the possibility of the government issuing a directive to the Bank of Canada. The Bank of Canada Act provides for the ultimate prerogative for monetary policy to lie with the elected federal government – as it should. Section 14 of the Act, which was added as an amendment in 1967, allows the government of the day – specifically the minister of finance – to give explicit instructions on policy to the Bank of Canada.2121 Note that the same provision also requires regular consultation between the governor and minister of finance to limit surprises and, therefore, the use of the directive power. If the minister were to do so, the directive and the government’s rationale would have to be published in the Canada Gazette and laid before Parliament within 15 days (if Parliament is sitting; if not, it would be 15 days after either house resumes sitting).2222 See Crow (2002) for more on why it is critical that the government has both the ultimate right to direct the Bank in terms of policy, and the requirement for full transparency with the public.

The amendment was a consequence of the so-called Coyne Affair of 1961 (see Siklos 2010). The Bank’s Governor, James Coyne, had openly criticized the government of the day in speeches, and the Diefenbaker government had, in turn, openly criticized the Bank’s monetary policy as too restrictive. In May 1961, the government introduced a terse bill declaring the governor’s position vacant. The bill was passed by the House of Commons, where the Diefenbaker government held a large majority, but it was overturned by the Liberal-dominated Senate, whereupon Coyne submitted his resignation. Louis Rasminsky, Coyne’s successor, demanded that the ultimate responsibility for monetary policy be clarified as a condition for accepting the governorship, which ultimately led to the amendment. In 1992, the Manley report recommended maintaining the government’s ability to issue a directive. Its use, however, was understood to trigger the governor’s immediate resignation (see Thiessen 2001, p. 32).2323 Siklos (2008) details the events leading to the amendment of the Bank of Canada Act, which allows for this possibility. He writes, “Coyne’s successor, Louis Rasminsky, echoing the plea made by his predecessor, would insist on the addition of a Directive into the Bank of Canada Act.”

Certainly, one could argue that the government needing to issue the directive at all, in such a public way, to influence monetary policy is a positive sign of operational independence. While true, it could also be abused. In today’s environment, it is worth asking whether the manner in which the directive is used can be refined to further reinforce operational independence.

Before getting into what such changes to section 14 might be, we note that the independence given to the Bank comes with necessary transparency and accountability. For example, under the Bank of Canada Act, “the Bank of Canada is required to submit each year its audited financial statements accompanied by a report by the governor to the finance minister. The Annual Report is presented to Parliament by the minister and a copy is published in the Canada Gazette.”2424 Bank of Canada. 2025. “Governance Documents.” January. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/about/governance-documents/#:~:text=The%20mandate%20of%20the%20Bank,published%20in%20the%20Canada%20Gazette. The Act also requires the Bank to be audited annually by two independent accounting firms simultaneously – the Bank is the only Crown corporation for which this is true (Rogers 2022). The minister of finance can expand the audit’s scope and request special reports. Finally, the Auditor General of Canada has legal authority to audit the Bank’s activities with respect to its role as fiscal agent of the government.

The Bank has also chosen to be transparent and accountable for its monetary policy actions. While not legislated to do so, the Bank of Canada publishes its Monetary Policy Report (MPR) four times a year, which includes its economic outlook and explains the rationale behind its eight fixed announcement date decisions with the overnight rate in press releases and news conferences. The governor and senior deputy governor also make frequent appearances in front of Parliament and the Senate around the time of the publication of the MPRs.

Against these measures of transparency and accountability, we think it is worthwhile to discuss the costs and the merits of the directive, and to consider whether it provides for the optimal balance between the operational independence necessary to guard against a rogue government and the need for elected officials to guard against a rogue governor. We see four options and will now present each, explaining the rationale for the one we prefer. We believe there needs to be a discussion on this topic as we approach the renewal in 2026 of the inflation-targeting framework agreement.

The first option is to leave things as they are. The merit of this is the government – and ultimately the public – being able to exert control over monetary policy should the Bank persistently fail to achieve its goals within the term of a governor. The costs of the directive stem from a government requesting policy actions that suit the current political situation. As we have pointed out, these actions may be in conflict with monetary stability, undermining the independence2525 By undermining the Bank’s overall independence from government, the results of its day-to-day operations will be hampered. and the credibility of the Bank of Canada.

The second option would be to remove the directive from the Bank of Canada Act, since the government already has the authority to fire the governor; they hold office subject to “good behaviour.”2626 See section 6(3)(a) of the Bank of Canada Act. For more background on these issues, see, for example, Paul Daly’s legal opinion: Daly, Paul. 2022. “Could a Prime Minister Poilievre Fire the Governor of the Bank of Canada?” Administrative Law Matters. September 13. https://www.administrativelawmatters.com/blog/2022/09/13/could-a-prime-minister-poilievre-fire-the-governor-of-the-bank-of-canada/. This alternative mechanism, however, has its own costs. Removal of the governor for lack of “good behaviour” would be a drawn-out process, where notice must be served to the governor who would then have the opportunity to respond and potentially challenge the government (legally) over their dismissal. This might then entail a lengthy period of uncertainty, which is conducive to neither monetary policy nor economic stability.

A third option would be to keep the directive as it is, but make its use subject to the inflation target having first been missed for a consistent period of time, and the governor providing a written explanation to the finance minister as to why this has occurred. If the government remained unsatisfied with the explanation, it could then issue the directive. This provides some limitation on when the directive could be used, but also allows the government to address concerns with the governor’s performance. The problem here is that we are linking the directive to the inflation target, and the inflation target is not in the Bank of Canada Act. As a result, we believe the Act would need to be reopened and inflation targeting added to the preamble.

A final option – and our preferred one – would be to seek a middle ground that recognizes the need to ensure the directive is only used sparingly, while also ensuring the situation is resolved speedily to avoid economic instability. Given today’s political environment, this middle-ground directive should come with increased scrutiny before coming into force, something we believe is missing from the current approach, even with the required regular consultation between the finance minister and governor under section 14.2727 The perceived danger of this type of interference in Canada increased in September 2023, when the finance minister and three provincial premiers weighed in publicly on the Bank’s decision to hold its overnight rate target at 5 percent. See Suhanic (2023) and Reuters (2023). Under this middle-ground approach, the government would have to present its directive in the form of a motion brought in front of Parliament by the minister of finance before being formally issued to the Bank of Canada. Such an amendment would allow the directive to be discussed in the House of Commons and to be subjected to the scrutiny of the opposition parties. It would also allow markets to react in advance of the issuing of the directive, giving room for markets to – in other words – discipline the government, thus raising the bar for issuing the directive in the first place.2828 Issues, such as when the motion would be tabled in Parliament if it were not sitting, would need to be resolved if this option were to be considered. We believe this option, by strengthening parliamentary oversight for monetary policy, reinforces operational independence for the Bank of Canada.

A second concern arises from the self-sufficiency of the Bank in financing its operations. The losses from QE performed during the COVID-19 pandemic have challenged, and are still challenging, the Bank’s finances. The Bank has accumulated large losses and, consequently, its negative equity position at the time of writing is around $9 billion.

As part of the Budget Implementation Act 2023, No.1, section 237 was inserted, overriding sections 27 and 27.1 of the Bank of Canada Act, allowing surpluses the Bank earns during the financial year to be applied to its retained earnings – as opposed to transferred to the government – until the earlier of (i) the Bank’s retained earnings getting back to zero or (ii) the Bank recovering its losses (defined as its profits equalling the losses from the government of Canada Bond Purchase Program from April 1, 2020, to April 25, 2022).

We believe it is necessary for there to be a permanent mechanism to deal with losses that accrue at the Bank of Canada for two reasons. First, a transparent mechanism clarifies for the public what the costs are of executing unconventional monetary policy measures. And second, once losses have accrued, the Bank’s operational independence still needs to be safeguarded. Having a permanent provision in place will help prevent these losses from being used to pressure the Bank into specific policy actions.2929 Ambler, Koeppl, and Kronick (2022) discuss in more detail the pressures on the Bank from a ballooning balance sheet and negative equity position.

The best option is to make use of the existing section 27 of the Bank of Canada Act. At present, it spells out how the Bank can retain a portion of its income to build its reserve fund until such time as the reserve fund reaches five times paid-up capital. It retains one-third of profits as long as the reserve fund is less than paid-up capital, then one-fifth as long as it is less than five times paid-up capital. As Tombe and Chen (2023) point out, however, it was not clear to the Bank that the Act would permit this retention under the circumstances; hence, the temporary section 237 in the Budget Implementation Act. Furthermore, section 27 does not allow for a full retention of future profits to build up reserves or remedy a negative equity position. We recommend a specific change to section 27 of the Act to clarify that this retention is indeed allowed and is at 100 percent when the Bank is in a negative equity position. Once the Bank’s equity position is back at zero, then it can return to the distribution between replenishing paid-up capital and remitting profits to the government, as currently stated in section 27.

Conclusion

Central bank independence is critical for monetary policy actions to be effective. The belief of Canadians that the Bank of Canada will do what it must to achieve its objective of low and stable inflation went a long way in stabilizing inflation expectations post-COVID, in turn allowing inflation to return to target sooner and with less difficulty than expected.

However, storm clouds are on the horizon as fiscal authorities in many countries look to add elements to central bank mandates. In Canada, climate change and inequality have been discussed in this respect, though no specific target has yet been included in final agreements between the federal government and the central bank. They are important goals in and of themselves, but are best handled by government policy, not central banks that lack the tools to deal with them. Moreover, the use of QE has muddied the waters between monetary and fiscal policy. Lastly, and critically, given the threats against operational independence of the central bank we are seeing south of the border, we are reminded there is always a risk of fiscal authorities overstepping and impeding the operational independence of central banks.

We suggest two measures that will further strengthen the operational independence of the Bank of Canada. First, we propose that the federal government be able to issue directives to the Bank only after they are presented in the House of Commons, thereby strengthening the role of parliamentary oversight and reinforcing the Bank’s operational independence. The upcoming renewal of the Bank’s mandate gives an opportunity to discuss the directive in more detail. Second, section 27 should be amended so that it explicitly allows the Bank to fully replenish its reserve fund when the Bank is in a negative equity position, before remitting any profits to the government. This change will add increased transparency and accountability to the Bank of Canada in the eyes of the public while strengthening its operational independence.

Central bank independence is key to monetary policy credibility and the economic gains this brings. This tradition has been upheld in Canada for decades. Let us not take it for granted. Indeed, let us strengthen it further.

The authors extend gratitude to Mawakina Bafale, Colin Busby, John Crean, David Dodge, David Laidler, Dave Longworth, Angelo Melino, John Murray, William B.P. Robson, Stephen Williamson, Mark Zelmer, and several anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. The authors retain responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

Appendix

The Bank of Canada’s Structure3030 See: Bank of Canada. 2025. “How Is the Bank of Canada Run?” February 18. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2025/02/how-is-the-bank-of-canada-run/.

The Bank of Canada Act defines how the Bank is structured and managed, and how it should operate. This allows the Bank to ensure its actions are consistent with the best interests of the Canadian economy as laid out in the preamble of the Act.

The executive of the Bank consists of a Governing Council, Executive Council, and Board of Directors, with each playing different roles.

Governing Council

The Bank’s Governing Council makes decisions about monetary policy and financial system stability.3131 We note that financial system stability is a shared responsibility with the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and others, e.g., the Department of Finance.

This group consists of the Governor, the Senior Deputy Governor, and the Deputy Governors. There are currently three Deputy Governors who are full-time Bank employees, and two who are academics external to the Bank who participate in deliberations on monetary policy and financial stability, but who do not have managerial responsibilities inside the Bank.

The Governor and Senior Deputy Governor are appointed by the Board of Directors, with the approval of Cabinet. Both are appointed for renewable seven-year terms.

The Governor oversees the core functions of the Bank, chairs the Board of Directors, and leads Governing Council. The Senior Deputy Governor chairs the Executive Council and is also a member of the Board of Directors.

Executive Council

The Executive Council is the main decision-making body for the overall management of the Bank. It also supports the decision-making functions of Governing Council and the Board of Directors.

It is made up of the Senior Deputy Governor; the Chief Operating Officer; the Executive Director of Payments, Supervision and Oversight; the Executive Director of Policy; and the Chief of Staff to the Governor.

Board of Directors

The Board of Directors oversees the Bank’s corporate, financial, and administrative activities, including strategic planning, risk management, finance and accounting, and human resource management. It is not directly involved in monetary policy decisions.

It is made up of the Governor, the Senior Deputy Governor, up to 12 independent directors, and the Deputy Minister of Finance (who is an ex officio, non-voting member).

The Bank’s View of Its Independence

The Bank’s “Explainer”3232 See: Bank of Canada. 2025. “Is the Bank of Canada Independent from Government?” February 18. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2025/02/is-bank-canada-independent-from-government/. notes that the Bank and the Government of Canada review and renew their agreement on the monetary policy framework every five years, and insists “how we implement monetary policy is up to us,” while also noting they are accountable to Parliament, the government, and all Canadians.

To explain how the Bank is accountable to the Canadian people, the document stresses its transparent communication, which includes: the monetary policy announcements themselves; press conferences after each announcement; summaries of Governing Council’s discussions leading to each decision; quarterly Monetary Policy Reports with updates on the economic and inflation outlooks; quarterly financial reports and an audited annual report; the results of business, consumer, and market participant surveys; information on corporate planning, accountability and disclosure, internal and external audits, and approaches to risk management; assessments on the state of financial stability; and regular appearances before House of Commons and Senate committees.

References

Alesina, Alberto, and Lawrence H. Summers. 1993. “Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance: Some Comparative Evidence.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 25: 151–162.

Alpanda, Sami, and Adam Honig. 2010. “Political Monetary Cycles and a De Facto Ranking of Central Bank Independence.” Journal of International Money and Finance 29: 1003–1023.

Ambler, Steve, Thorsten V. Koeppl, and Jeremy Kronick. 2022. “The Consequences of the Bank of Canada’s Ballooned Balance Sheet.” Commentary 631. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. November.

Ambler, Steve, Thorsten V. Koeppl, and Jeremy Kronick. 2025. “Flexible Inflation Targeting Beats a Dual Mandate: Lessons for Canada’s 2026 Framework Renewal.” E-Brief. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. May.

Bade, Robin, and Michael Parkin. 1988. “Central Bank Laws and Monetary Policies.” Working Paper. University of Western Ontario, Canada. Accessed at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/245629808_Central_Bank_Laws_and_Monetary_Policy.

Bandaogo, Mahama. 2021. “Why Central Bank Independence Matters.” World Bank Research & Policy Briefs No. 53. November. Accessed at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/284641638334557462/pdf/Why-Central-Bank-Independence-Matters.pdf.

Barro, Robert J., and David B. Gordon. 1983. “Rules, Discretion and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy.” Journal of Monetary Economics 12: 101–121.

Benigno, Pierpaolo, and Salvatore Nistico. 2020. “Non-neutrality of Open-Market Operations.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 12: 175–226.

Berger, Helge, Jakob De Haan, and Sylvester Eijffinger. 2001. “Central Bank Independence: An Update of Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Economic Surveys 15: 3–40.

Binder, Carola Conces. 2021. “Political Pressure on Central Banks.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 53: 715–744.

Brumm, Harold J. 2002. “Inflation and Central Bank Independence Revisited.” Economics Letters 77: 205-209.

______________. 2011. “Inflation and Central Bank Independence: Two-way Causality?” Economics Letters 111: 220–222.

Chant, John. H. 2022. The Ebb and Flow of Bank of Canada Independence. Vancouver, Fraser Institute. Accessed at: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/ebb-and-flow-of-bank-of-canada-independence.pdf.

Cochrane, John. H. 2023. The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Crow, John. 2002. Making Money: An Insider’s Perspective on Finance, Politics, and Canada's Central Bank. Etobicoke ON, John Wiley & Sons Canada.

Cukierman, Alex, Steven Webb, and Bilin Neyapti. 1992. “Measuring the Independence of Central Banks and Its Effect on Policy Outcomes.” The World Bank Economic Review 6: 353–398.

Dall’Orto Mas, Rodolfo, Benjamin Vonessen, Christian Fehlker, and Katrin Arnold. 2020. “The Case for Central Bank Independence: A Review of Key Issues in the International Debate.” European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series No. 248. October. Accessed at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/3b9f8416-4597-11eb-b59f-01aa75ed71a1.

Debelle, Guy, and Stanley Fischer. 1994. “How Independent Should a Central Bank Be?” in Jeffrey Fuhrer (ed.), Goals, Guidelines, and Constraints Facing Monetary Policymakers. Proceedings of a Conference held in North Falmouth, Massachusetts, Boston MA, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 195–221.

Desroches, Brigitte, Sharon Kozicki, and Laure Simon. 2024. “Monetary Policy Governance: Bank of Canada Practices to Support Policy Effectiveness.” Bank of Canada Staff Discussion Paper No. 2014-14. September. Accessed at: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/sdp2024-14.pdf.

Dorich, José, Rhys Mendes, and Yang Zhang. 2021. “The Bank of Canada’s ‘Horse Race’ of Alternative Monetary Policy Frameworks: Some Interim Results from Model Simulations.” Bank of Canada Staff Discussion Paper 2021-13. August. Accessed at: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/sdp2021-13.pdf.

Garriga, Ana, and Cesar Rodriguez. 2020. “More Effective Than We Thought: Central Bank Independence and Inflation in Developing Countries.” Economic Modelling 85: 87–105.

Garriga, Ana. 2016. “Central Bank Independence in the World: A New Data Set.” International Interactions 42: 849–868.

Haldane, Andy. 2020. “What Has Central Bank Independence Ever Done for Us?” Speech, UCL Economists’ Society Economics Conference. November. Accessed at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2020/what-has-central-bank-independence-ever-done-for-us-speech-by-andy-haldane.pdf.

Hall, Robert, and Ricardo Reis. 2015. “Maintaining Central-Bank Financial Stability under New-Style Central Banking.” NBER Working Paper No. 21173. May. Accessed at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21173/w21173.pdf.

Klomp, Jeroen, and Jakob De Haan. 2010. “Inflation and Central Bank Independence: A Meta Regression Analysis.” Journal of Economic Surveys 24: 593–621.

Kronick, Jeremy, and Luba Petersen. 2022. Crossed Wires: Does Fiscal and Monetary Policy Coordination Matter? Commentary 633. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. December.

Kydland, Finn E., and Edward C. Prescott. 1977. “Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans.” Journal of Political Economy 85: 473–492.

Laidler, David, and William B.P. Robson. 1994. The Great Canadian Disinflation: The Economics and Politics of Monetary Policy in Canada, 1988-1993. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Laidler, David, and William B.P. Robson. 2004. The Two Percent Target: Canadian Monetary Policy Since 1991. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Murray, John. 2021. “Mission Creep and Monetary Policy.” E-Brief 317. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. June.

Nordhaus, William. 1975. “The Political Business Cycle.” Review of Economic Studies 42: 169–190.

Parliament of Canada. 1992. The Mandate and Governance of the Bank of Canada. Sub-Committee on the Bank of Canada of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, 34th Parliament, 3rd session, Report No. 1 (February 24). Accessed at: https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.com_HOC_3403_41_6/1.

Powell, James. 2005. A History of the Canadian Dollar. Ottawa: Bank of Canada.

Ragan, Christopher. 2021. “Are Dangers Lurking Within the Bank of Canada’s New Mandate?” MAX Policy. Max Bell School of Public Policy. December. Accessed at: https://www.mcgill.ca/maxbellschool/max-policy/dangers-lurking-bank-canadas-new-mandate.

Reuters. 2023. “Bank of Canada’s Macklem: Provincial Premiers Risk Undermining Bank’s Independence.” October 24. Accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/markets/bank-canadas-macklem-warned-premiers-about-cenbanks-independence-canadian-press-2023-10-24/.

Rogers, Carolyn. 2022. “The Bank of Canada: A matter of trust.” Speech to Women in Capital Markets. May 3.

Siklos, Pierre. 2010. “Revisiting the Coyne Affair: A Singular Event that Changed the Course of Canadian Monetary History.” Canadian Journal of Economics 43: 994–1015.

Sturm, Jan-Egbert, Jakob De Haan. 2001. “Inflation in Developing Countries: Does Central Bank Independence Matter? New Evidence Based on a New Data Set.” Working Paper No. 511, Ifo Institute. June. Accessed at: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/75760.

Suhanic, Gigi. 2023. “‘Everybody Should Just Shut Up’: Bank of Canada’s Independence Under Pressure From Political Comments.” Financial Post. September 16. Accessed at: https://financialpost.com/news/economy/bank-of-canada-independence-under-pressure-political-comments.

Thiessen, Gordon. 2000. “Can a Bank Change? The Evolution of Monetary Policy at the Bank of Canada 1935-2000.” Lecture to the Faculty of Social Science, University of Western Ontario, October 17. Accessed at: https://www.bis.org/review/r001020b.pdf.

Thiessen, Gordon. 2001. The Thiessen Lectures. Ottawa: Bank of Canada. Accessed at: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/thiessen-eng-book.pdf.

Tinbergen, Jan. 1952. On the Theory of Economic Policy. Amsterdam, North-Holland.

Tombe, Trevor, and Yu (Sonja) Chen. 2023. “Reversal of Fortunes: Rising Interest Rates and Losses at the Bank of Canada.” E-Brief 337. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. January.

Williamson, Stephen. 2021. Weighing the Options: Why the Bank of Canada Should Renew Inflation Targeting. Commentary 599. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. April.

This E-Brief is a publication of the C.D. Howe Institute.

Jeremy Kronick is Vice-President, Economic Analysis and Strategy at the C.D. Howe Institute.

Steve Ambler is professeur émérite, Département des sciences économiques, École des sciences de la gestion, Université du Québec à Montréal, and a Fellow-In-Residence and the David Dodge Chair in Monetary Policy at the C.D. Howe Institute.

Thorsten Koeppl is Professor of Economics, the Robert McIntosh Fellow, and RBC Fellow at Queen’s University, and a Fellow-In-Residence at the C.D. Howe Institute.

This E-Brief is available at www.cdhowe.org.

Permission is granted to reprint this text if the content is not altered and proper attribution is provided.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and are not attributable to their respective organizations. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

Related Publications

- Research