Home / Publications / Research / Federal Expenditure Review: Welcome, But Flawed

- Research

- |

Federal Expenditure Review: Welcome, But Flawed

Summary:

| Citation | John Lester. 2025. "Federal Expenditure Review: Welcome, But Flawed." ###. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Federal Expenditure Review: Welcome, But Flawed – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Federal Expenditure Review: Welcome, But Flawed |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/federal-expenditure-review/ |

| Published Date: | August 14, 2025 |

| Accessed Date: | January 30, 2026 |

Outline

Outline

Authors

Related Topics

Press Release

Files

For all media inquiries, including requests for reports or interviews:

- The federal government’s “comprehensive spending review” is a misnomer. Its narrow focus and carve outs limit the effective coverage to about a third of program spending.

- The review will deliver at most $22 billion in savings in 2028/29. That is not ambitious enough. Savings of around $50 billion are required to put federal finances on a fair and prudent path.

- To maximize the benefits of expenditure restraint, the scope of the review must be broadened to include all spending, including measures delivered through the tax system. The across-the-board approach must also be abandoned in favour of reductions targeted at the poorest-performing programs government wide.

Introduction

The federal “comprehensive” expenditure review was launched in early July through letters to ministers from the minister of finance. These letters were not made public, but various media outlets have prepared summaries. Based on these summaries, the review aims to achieve up to a 15 percent reduction in government operating expenditures in 2028/29. The government’s definition of operating expenditures appears to be compensation and other costs of running government departments, agencies, and Crown corporations, and “other transfers,” defined as total transfers less major transfers to persons and other levels of government. These expenses are almost half of program spending forecast for the current fiscal year, but I estimate that exemptions will reduce the coverage of the review to just under a third of program spending. As a result, the fiscal savings from the review will amount to about $22 billion in 2028/29, less than half the amount required to put federal finances on a fair and prudent path.

To make up the shortfall, the scope of the review should be broadened rather than making deeper cuts to the narrow base. The spending review should include not only all program spending but also programs delivered through the tax system. In addition, the government should completely abandon the across-the-board approach in favour of reductions targeted at the poorest performing programs government wide. An across-the-board approach makes it impossible to maximize the net benefit of reducing spending because programs are not compared across departments. This shortcoming is magnified by the narrow focus of the review, which makes it inevitable that some of the programs cut or modified will be providing greater benefits than some of the programs untouched by the review.

It takes time to identify underperforming programs and to build political support for substantial spending reductions. The government should therefore proceed in two stages. First, immediately apply a multi-year cap on the day-to-day costs of running the government that would force managers to realize efficiencies in program delivery and internal operations. Second, set up a longer-term process to identify underperforming programs and build consensus for change.

Relatively Small Savings from the Expenditure Review

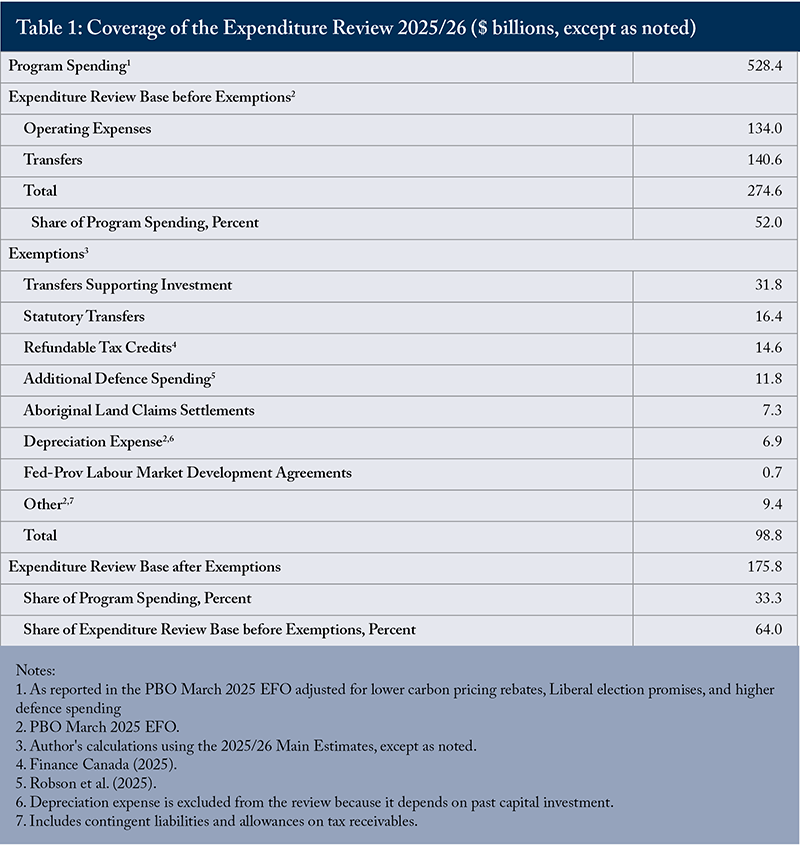

The spending review focuses on operating expenditures, but with substantial carve outs. For example, programs that support capital investment by the private sector or other levels of government are exempt, and it appears that transfers authorized through legislation will not be subject to review. In a disappointing lack of transparency, the amount of spending affected by these carve outs has not been made public. I estimate that exempting transfers that support investment reduces the review base by about $32 billion, while the carve out for statutory transfers and refundable tax credits eliminates roughly $15 billion each (Table 1). In addition, the proposed increases in defence spending will be exempt.

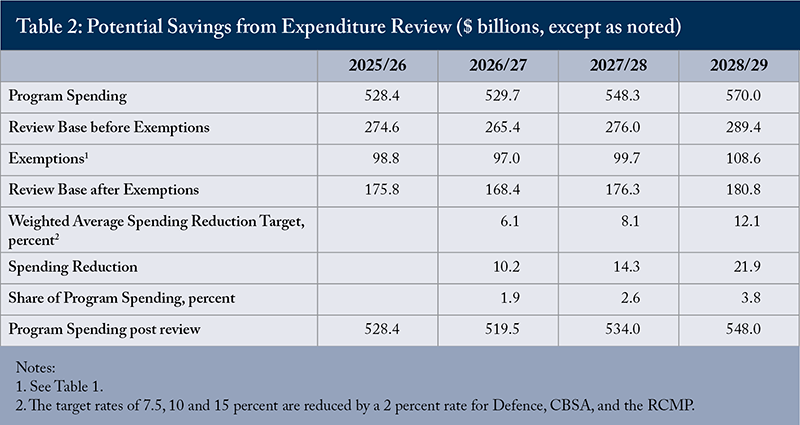

With all these carve outs, spending in 2025/26 subject to the “comprehensive” review will amount to $175 billion, which is about two-thirds of operating expenditures but only one third of program spending. While most departments have a 15 percent target reduction in spending, the Department of National Defence, the Canadian Border Services Agency, and the RCMP have a 2 percent target. With these adjustments, achieving the targeted reductions would lower program spending in 2028/29 by $22 billion relative to its baseline level, or just under 4 percent (Table 2).

A More Ambitious Target

The federal government’s latest fiscal anchor is to balance the “operating budget” by 2028/29. Under Public Sector Accounting Standards (PSAS), government spending excludes capital outlays but includes the depreciation expense associated with capital spending. Balancing the federal budget is therefore equivalent to balancing the operating budget, as conventionally defined. However, the federal government is planning to depart from PSAS by redefining capital outlays to include “new incentives that support the formation of private sector capital (e.g., patents, plants, and technology) or which meaningfully raise private sector productivity” (Liberal Party of Canada 2025) as well as transfers to other levels of government that support investment.

The government does not intend to change the format of its audited financial statements, so the proposed change will create a disconnect between the two presentations of the deficit. This will cause a substantial reduction in transparency and accountability (Robson et al. 2025). Specifically, it will justify debt financing of certain transfers without incurring the associated depreciation expense, which removes the incentive for fiscal discipline in using transfers to support investment. Further, since provincial deficits are also net of capital spending, removing transfers that support investment by other levels of government from the federal deficit will distort the fiscal position of the overall public sector. The government should continue to use the conventional definition of an operating budget.

It should also revert to its prior practice of using the debt-to-GDP ratio as a fiscal anchor and commit to reducing the debt ratio over the forecast horizon. This recommendation is based on the view that debt-financing of current expenditures is unfair to future generations because it harms economic performance and will lead to higher tax rates or lower spending if debt levels become unsustainable due to an economic downturn (Lester and Laurin 2025). Abstracting from cyclical conditions, the optimal budget deficit is therefore zero; however, achieving this target over the next several years would be too disruptive. A prudent and fair fiscal framework would show, at a minimum, the debt ratio edging down over the forecast horizon and heading toward its level in 2024/25 thereafter.

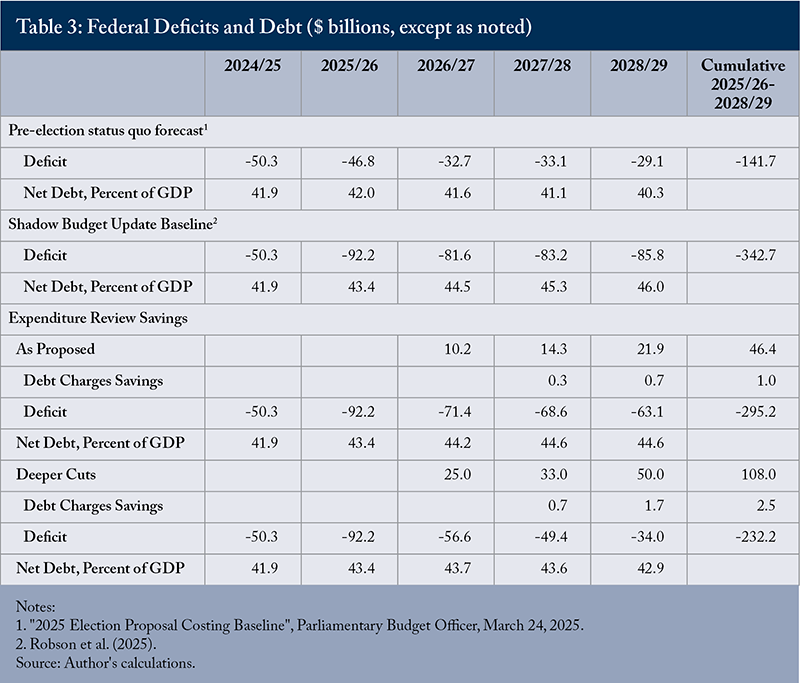

The pre-election status quo forecast showed deficits and the debt ratio declining over the forecast horizon (Table 3). Policies recently implemented and the initiatives in the Liberal Party election platform will almost double the current year’s deficit and raise the debt ratio by almost 1.5 percentage points relative to the pre-election baseline. The deficit is projected to remain high over the forecast horizon, causing the debt ratio to rise about 2.5 percentage points over the three years ending in 2028/29, instead of falling 1.7 percentage points in the pre-election status quo forecast.

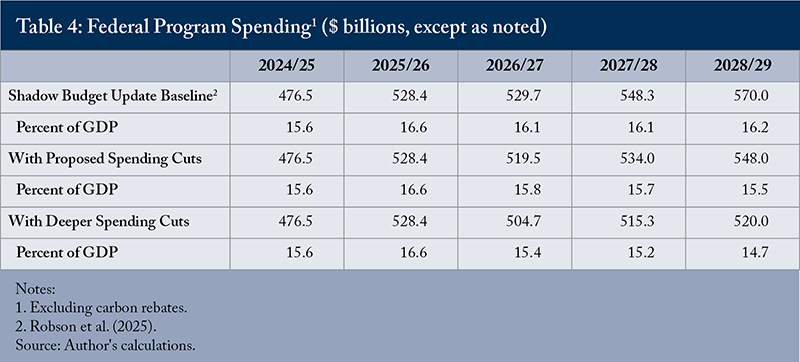

The maximum $47 billion cumulative savings from expenditure review are not enough to prevent a rise in the debt ratio over the forecast horizon. Additional cumulative fiscal consolidation of approximately $60 billion is required to achieve a lower debt ratio in 2028/29 than in 2025/26. The additional consolidation could, in principle, be achieved by tax increases or further spending reductions. However, the recent election revealed a preference for tax reductions rather than increases. Further, the US has made permanent the tax cuts implemented in Trump’s first term, which will make increases in business taxes particularly damaging. Finally, the personal income tax burden on Canadians was the fifth highest in the OECD in 2022.1Source: the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Global Revenue Statistics Database https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/global-revenue-statistics-database.html. The lower debt target should therefore be achieved through further spending reductions (see Table 3, “Deeper cuts” scenario). This “deeper cuts” scenario would reduce program spending as a share of GDP to 14.7 percent in 2028/29 (Table 4), which is slightly above its average from 2014/15 to 2019/20. Program spending would be approximately unchanged from 2025/26, but would still be 9 percent higher than in 2024/25.

Shortcomings of the Review Process

The expenditure review has two components. The first is to eliminate or restructure programs that are not meeting their objectives, are not core to the federal mandate, or duplicate programming by other levels of government.2Tasker, John Paul, and David Cochrane. 2025. “Carney’s Cabinet Asked to Find ‘Ambitious Savings’ Ahead of Fall Budget.” CBC News. July 7. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/ottawa-spending-cuts-1.7579022. The second component is raising the productivity of public sector employees.

The expenditure review is a narrowly focused exercise that essentially imposes across-the-board cuts determined at the department level. This approach has the advantage of timeliness and economizing on the scarce time of politicians and civil servants. However, it cannot maximize the net benefit from expenditure restraint, primarily because across-the-board cuts make it impossible to eliminate or restructure the programs that are performing poorest overall. Each department can, in principle, identify its programs that are not meeting their objectives, but unless they are compared across departments, some programs chosen for elimination or restructuring will be performing better than some programs retained by other departments.

The narrow focus of the review amplifies this weakness: the poorest performing programs in the review base may be providing a higher net benefit than some of the programs outside its scope. Within operating expenditures, the review exempts statutory programs and refundable tax credits. The latter are part of program spending because the payment is independent of the tax status of the recipient. Statutory payments include student loans and grants, farm income support programs, and disability payments. Refundable tax credits include the Canada Workers Benefit, the enhanced Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) tax credit, and several measures that support investment in clean technology. These programs differ from those included in the review only in that they are slightly more time consuming to change,3Changing statutory programs and refundable tax credits requires legislative action for each program, while changes to many non-statutory, or voted programs, can be made at once through the Estimates process. so their exclusion from the review is difficult to justify.

The exclusion of provisions supporting investment by the private sector or other levels of government is similarly problematic.4Many programs that support investment, such as the Clean Technology Investment Tax Credit, are delivered as refundable investment tax credits. For example, payments under the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy are part of transfers subject to review but are excluded because they support private sector investment. Excluding investment-supporting programs signals that investment is a government priority, but a better approach would have been to establish an investment expenditure “envelope” and review measures within it with an eye to improving the effectiveness of spending through reallocations and replacement of ineffective programs.

Exempting major transfers to individuals, such as support for seniors and children, and to other levels of government, such as the Canada Health Transfer, reduces the review base by about half. It is highly unlikely that an objective ranking of the performance of all federal transfers would indicate that all the major transfers are performing better than all other transfer payments, so their exclusion from the review means forgoing opportunities for improving the net benefit of expenditure reduction.

In addition to excluding approximately two-thirds of program spending, the review does not cover programs delivered through the tax system. Finance Canada (2025) reports that some $150 billion in tax revenue is forgone through tax credits, special deductions, and preferential tax rates that favour specific activities and types of income. Measures accounting for about two-thirds of this amount address problems such as the tax treatment of savings and income paid to non-residents, which makes them more of an issue for tax reform than for a spending review. The expenditure review should cover an estimated $54 billion in tax-based measures that are comparable in purpose and function to direct spending programs.5Author’s calculations based on a detailed review of the tax expenditure accounts. With this inclusion, the potential expenditure review base is $582 billion, of which the “comprehensive” expenditure review covers 30 percent.

Extending the scope of the spending review to include these tax-based spending programs is important for fairness and efficiency. Consider federal support for seniors, which comprises benefits through the Old Age Security and Guaranteed Income Supplement programs and benefits delivered through the tax system, such as the age credit, the pension income credit, and pension income splitting. When assessing whether the amount of support provided to seniors is appropriate, it is important that all government measures be included and if adjustments are deemed necessary, that the least efficient measures be adjusted first.

A second shortcoming of the review may be insufficient direction from the centre on which programs subject to review should be eliminated because they are not core to the federal mandate, or equivalently, not aligned with current priorities. The government has set out its priorities in the mandate letter to ministers, but they are too general to provide guidance on which programs should be dropped because they no longer help achieve key government objectives. The government has acknowledged this issue by setting lower targets for reductions in defence and border security spending, as well as by excluding programs that support investment by the private sector and other levels of government.

A Better Approach

Ideally, a targeted review of all program spending and tax-based spending would be implemented in two stages, accompanied by an ongoing communications exercise. The first stage should be implemented now, with a status report in the upcoming budget. It would build on existing efforts to measure and improve the efficiency of service delivery (Canada 2025). For example, measures of efficiency, such as the total cost per passport processed, are being developed. These efficiency measures provide a useful benchmark for assessing progress in improving service delivery, particularly since they will be accompanied by measures of service standards.

The drive to improve service delivery should be reinforced by a multi-year cap on the day-to-day operating costs of the federal government, excluding military personnel. More than half of these costs arise from compensation payments and the purchase of professional services, such as consulting, used to fund departmental operations. The cap should be restrictive enough to force managers to find ways to deliver programs and internal services more efficiently, but realistic enough to prevent unwarranted declines in service standards. In addition to bottom-up initiatives, options for improving efficiency should be developed and funded centrally.

The second stage of expenditure review would be targeted reductions covering all program spending and programs delivered through the tax system. The goal of the second stage would be to reduce spending from its baseline level in 2028/29 by about $50 billion, less the savings from the operating expenses cap and the induced effect on operating costs from lower spending on transfers. This process will take some time. The government should set out its expenditure plan, including projected savings from the review, in the 2026 budget. Except for cyclically induced changes in spending, the government should commit to this expenditure plan for the next four years.6See Lester (2024) for details on this proposal. The ongoing results of the targeted review should be announced in budgets starting in 2026 and ending in 2029.

The first step in this stage would be to identify and eliminate programs that are duplicating services provided by other levels of government. The second step would be to identify and eliminate or restructure programs that are not aligned with government priorities. This step requires direction from the centre. One possibility would be to develop centrally defined policy envelopes and to require departments to justify the inclusion of each of their programs into at least one envelope. A special cabinet committee would develop the policy envelopes, review the classification of programs made by departments, and determine which programs would be eliminated.

In a third step, departments would submit proposals to restructure or eliminate programs that are not achieving their objectives. However, if programs are assessed against their ability to meet their objectives, these objectives must be thoughtfully specified. Under the current performance management system, program objectives are almost always specified in terms of the response of program beneficiaries. For example, a business subsidy program will be deemed to have met its objectives if investment, output, or employment increases because of the subsidy. However, that’s not a stringent test: it would be very surprising if firms didn’t respond favourably to a subsidy. When objectives are framed in this way, very few subsidy programs fail to achieve their objectives.

The question that should be asked instead is: Are Canadians in general richer or poorer because of the subsidy? Unfortunately, this question is rarely asked. I have reviewed 48 evaluations prepared from 2020 to 2024 in eight departments and found that only four went beyond assessing impacts on program beneficiaries to examine whether programs represented value for taxpayer money (Lester 2024). This means very little of the extensive published evaluation work by departments can be used in the spending review.

Three of the four evaluations that assessed value for money used benefit-cost analysis, which is the gold standard for such assessments. Benefit-cost analysis should be applied more widely in program evaluation, using the assessment of the Federal-Provincial Labour Market Development Agreements by Employment and Social Development Canada as a model of best practice. In addition to labour market development programs, this approach could be applied to business subsidies and climate change mitigation and adaptation measures, which have benefits and costs that can be measured in monetary terms. These programs can be ranked by their net social benefits, allowing close comparisons of peer programs and qualitative comparisons across program categories. Programs with benefits smaller than their costs should be eliminated or restructured to achieve a positive net benefit. The assessment should consider how programs interact, particularly with respect to the stacking of benefits.

As discussed in Lester (2024), social programs and other measures with a fairness goal require a more nuanced approach because the benefits of such programs are subjective.7The extensive empirical research on the economic benefits of greater income equality is inconclusive: the impact could be positive or negative (Baselgia and Foellmi 2022). Reliable estimates of their economic impact, whether positive or negative, would allow programs to be ranked by their net benefits, providing a more definite basis for adding considerations of fairness. One possibility is to calculate a cost-effectiveness ratio in which the numerator is some measure of the amount of income redistribution achieved and the denominator is the fiscal cost of the measure. The income redistribution measure could be an indicator of the change in the overall distribution of income, such as the Gini coefficient, or a measure based on a comparison of top or bottom incomes with average incomes. Using this ratio to rank programs implicitly assumes that the gross social benefits of a given amount of income redistribution do not change across programs and that the gross social cost of the measure is proportional to its fiscal cost. Neither of these assumptions is likely to be true, but they will be less problematic for programs with similar characteristics. The cost-effectiveness ratio should be supplemented with information on how the program fits into other measures providing support to the target population.

While simpler than a full-fledged benefit-cost analysis, calculating cost-effectiveness ratios can still be resource intensive. In some cases, it may be sufficient to present information on the distributional impacts of fairness measures, their fiscal cost, including administration expenses, and a description of program beneficiaries. This information would allow politicians to form an evidence-based opinion on the value for money of social programs.

Benefit-cost and cost-effectiveness analyses are more likely to contribute to the expenditure review if responsibility, including funding, for their deployment comes from a coordinating authority. The Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS), in consultation with departments, should draw up a list of programs to be analyzed, develop a work program, and ensure its completion. This would allow the scope of the work to be narrowed substantially. Programs with an economic development or climate change objective should be screened to determine if they are addressing a market failure. A necessary condition for a program to realize a net social benefit is that government intervention is required to obtain an efficient allocation of labour and capital. It follows that if a program does not address a market failure, it will harm rather than help economic performance, and that eliminating it would make Canadians richer. As a result, the evaluation task can be substantially simplified to determining if the program addresses a market failure.

TBS should take advantage of Statistics Canada’s offer to undertake, on a cost recovery basis, the data analysis that would be the foundation for a benefit-cost analysis of selected programs (Frenette et al. 2025).8The paper includes a summary of an evaluation of the Canada Summer Jobs (CSJ) program. The key findings of the evaluation were that CSJ participants had better labour market outcomes than non-participants and that the program did not always reach the most vulnerable youth. Private sector studies already in the public domain (Lester 2013, 2017, 2021, and 2025) could also be reviewed and used as appropriate.

Benefit-cost and cost-effectiveness analyses are imperfect evaluation tools, but they can provide policymakers with objective evidence on the value for money of government programs. The key question is whether policymakers will be willing to incur the wrath of voters who see a reduction in their benefits, even if the program in question fails to provide value for money. Success is more likely if the goals and findings of the review are communicated to Canadians in a way that builds support for change. Effective communication must make the case for taking action to get federal finances on a fair and prudent path and carefully explain the reasons for eliminating and restructuring programs. Expanding the scope to cover all spending, including tax-based measures, can spread the impact of restraint more broadly across beneficiaries. The resulting perception of fairness will make it easier to implement the restraint measures.

Conclusion

The federal government’s “comprehensive spending review” falls short of its name and purpose. By excluding large swaths of program spending through exemptions and carveouts, the review will cover only about a third of total spending, limiting potential savings to an estimated $22 billion in 2028/29 – far below the roughly $50 billion needed to put federal finances on a fair and prudent path. To maximize the benefits of expenditure restraint, the review must expand to cover all areas of government spending, including tax-based measures, and shift away from blunt, across-the-board cuts toward more strategic reductions focused on programs that deliver the least value for money. The prospects for using the expenditure review to eliminate poorly performing programs will be greatly enhanced by a thoughtful communications strategy.

The author extends gratitude to Brian Ernewein, Alexandre Laurin, Benoît Robidoux, William B.P. Robson, and several anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. The author retains responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

References

Baselgia, Enea, and Reto Foellmi. 2022. “Inequality and Growth: A Review on a Great Open Debate in Economics.” WIDER Working Paper Series, no. wp-2022-5. https://ideas.repec.org/p/unu/wpaper/wp-2022-5.html.

Canada, Government of 2025. “The State of Service.” March. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/esdc-edsc/documents/corporate/reports/state-of-service-2025/the-state-of-service-annual-report-2025.pdf.

Finance Canada. 2025. Report on Federal Tax Expenditures - Concepts, Estimates and Evaluations 2025. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/services/publications/federal-tax-expenditures/2025.html.

Frenette, Marc, Winnie Chan, and Tomasz Handler. 2025. Leveraging Statistics Canada Data Integration Opportunities for Program Evaluation. Vol. 5, No.3. Economic and Social Reports. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/36-28-0001/2025003/article/00002-eng.pdf?st=agznUSSg.

Lester, John. 2013. “Tax Credits for Foreign Location Shooting of Films: No Net Benefit for Canada.” Canadian Public Policy 39 (3): 451–72.

Lester, John. 2017. “Policy Interventions Favouring Small Business: Rationales, Results and Recommendations.” University of Calgary School of Public Policy Research Paper 10 (11): 55.

Lester, John. 2021. “Benefit-Cost Analysis of Federal and Provincial SR&ED Investment Tax Credits.” University of Calgary School of Public Policy Research Paper 14 (1). https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Tax-Credits-Lester.pdf.

Lester, John. 2024. “Minding the Purse Strings: Major Reforms Needed to the Federal Government’s Expenditure Management System.” E-Brief 359. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. September 5. https://cdhowe.org/publication/minding-purse-strings-major-reforms-needed-federal-governments-expenditure/.

Lester, John. 2025. “An Evaluation of the Industrial Research Assistance Program.” Research Paper. School of Public Policy. https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/FP-10-IndResearch-Final.pdf.

Lester, John, and Alexandre Laurin. 2025. Canada’s Debt Problem: What Can Be Done? A Report on the Institute’s 2024 Debt Conference. Commentary 675. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. January 28. https://cdhowe.org/publication/canadas-debt-problem-what-can-be-done-a-report-on-the-institutes-2024-debt-conference/.

Robson, William B.P., Don Drummond, and Alexandre Laurin. 2025. “The Fiscal Update the Government Should Have Produced, and the Budget Canada Needs.” E-Brief 374. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. July 3. https://cdhowe.org/publication/the-fiscal-update-the-government-should-have-produced-and-the-budget-canada-needs/.

The views expressed here are those of the author and are not attributable to their respective organizations. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

Related Publications

- Intelligence Memos

- Intelligence Memos

- Research