Home / Publications / Intelligence Memos / Confronting Canada’s Fiscal Future

- Intelligence Memos

- |

Confronting Canada’s Fiscal Future

Summary:

| Citation | Trevor Tombe. 2025. "Confronting Canada’s Fiscal Future." Intelligence Memos. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Confronting Canada’s Fiscal Future – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Confronting Canada’s Fiscal Future |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/confronting-canadas-fiscal-future/ |

| Published Date: | August 1, 2025 |

| Accessed Date: | November 15, 2025 |

Outline

Outline

Authors

Related Topics

Files

From: Trevor Tombe

To: Deficit observers

Date: August 1, 2025

Re: Confronting Canada’s Fiscal Future

Canada’s pledge to spend 5 percent of GDP on defence, if acted upon, will come with potentially large fiscal costs. Following through will require either sustained deficits, tax increases, or difficult reductions in other areas of federal spending. More likely, it will involve a combination of all three – at a scale far beyond what many Canadians may realize.

Let’s take a look why.

The federal government’s near-term objective is to achieve faster economic growth and return to a balanced operating budget within three years. But even if successful, that will not be enough to address Canada’s broader fiscal challenges – either in the short or long term.

In the short term, a recent C.D. Howe Institute analysis offers a sobering outlook. After accounting for recent policy decisions – including the cancellation of the capital gains tax changes, the reduction in the first income tax bracket to 14 percent, the removal of the GST for first-time homebuyers, the shelving of the digital services tax, and various Liberal campaign platform commitments – the federal deficit is projected to exceed $92 billion this year. Next year, it may approach $82 billion. These levels, if sustained, would push the net-debt-to-GDP ratio from its current level of roughly 43 percent to more than 44 percent by 2028.

While these figures are not yet alarming in an international context, the longer-term trajectory is more troubling.

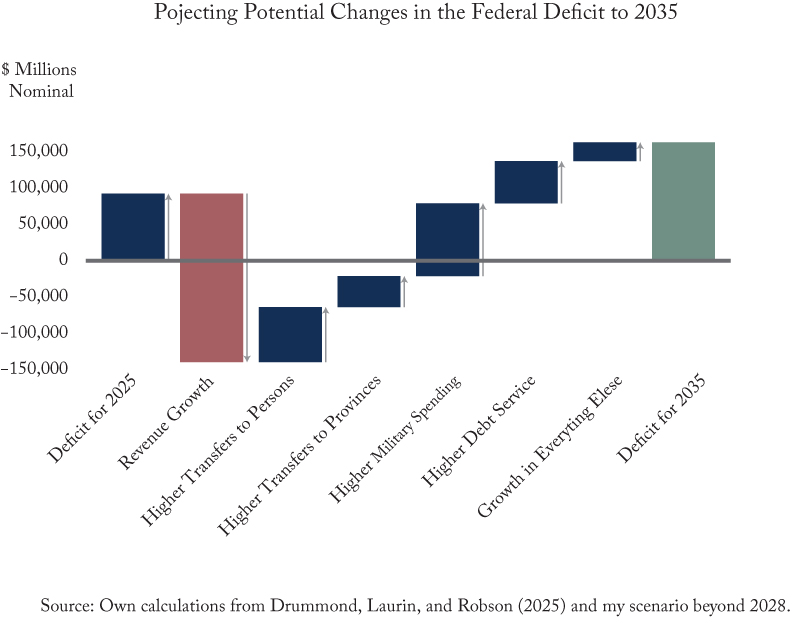

Building on the C.D. Howe projections, I constructed my own forecast for federal finances to 2035. Nothing too sophisticated, but entirely reasonable to provide a good sense of scale.

Under conservative assumptions – current tax cuts stay, platform commitments are phased out after 2028, defence gets its 5 percent by 2035 (but 1.5 percentage points associated with “critical infrastructure, defend networks, ensure civil preparedness and resilience, innovate, and strengthen the defence industrial base” coming from reallocations of expenditures rather than net new spending), and baseline revenue and program spending grow with the economy – the deficit would decline modestly to $78 billion by 2029, but then resume its upward climb to reach more than $160 billion by 2035.

Despite robust economic growth (of approximately 1.8 percent real growth per year over this decade), which generates increases in revenues, federal debt in this scenario could potentially rise to well above 50 percent of GDP by that year. The largest single contributor is the planned increase in military spending. But combine higher transfers to people and provinces, and you add even more. Rising debt also means rising interest payments too. Overall, growth in all non-transfer, non-interest, and non-military spending accounts for a negligible amount of the rising deficit.

One could, of course, quibble with some of the underlying assumptions here. But if this is even close to reasonable, then it is unsustainable. A rising debt to GDP simply cannot go on forever without some sort of fiscal adjustment.

To get a sense of the scale, it helps to look at where federal money actually goes. The largest share is transfers to individuals – especially seniors – which stand at $85 billion today and are projected to top $104 billion by 2029. Add in programs like the Canada Child Benefit and EI, and the total could exceed $170 billion by the end of the decade. By 2035, I project it will reach around $220 billion. Transfers to provinces could surpass $150 billion, and defence spending may end up even higher.

If spending less in these areas is off the table – as leaders across the political spectrum often insist – there’s not much else left to trim. If transfers to people and provinces, interest payments, and military spending are all left untouched, then balancing the budget by 2035 would require eliminating most of all remaining federal spending.

Looking for cuts only within the roughly one-third of the budget that excludes interest payments, defence, and transfers leads to a scale of reduction that, it’s fair to say, isn’t realistic.

That leaves two options: Raise new revenues or slow the growth of transfers to individuals and provinces. Some are already proposing higher taxes – such as an increase to the GST – as a way to close the gap. But if the goal is to support investment, productivity, and growth, adding to the tax burden may work at cross purposes.

But if higher taxes are off the table, then rethinking transfers – especially to seniors – becomes unavoidable. That could mean raising the eligibility age for Old Age Security, tightening income thresholds, adjusting benefit phase-outs, or fundamentally redesigning how provincial transfers grow over time.

None of these choices are easy, and all involve trade-offs. But the longer we wait, the fewer options we’ll have – and the more painful the adjustments will be. With big spending increases on the horizon and limited room to absorb them, now is the time to take a hard look at Canada’s fiscal future and start making a plan to keep it on a sustainable track.

The federal government isn’t alone in facing these challenges. Provinces, too, are under growing pressure from aging populations, rising healthcare costs, and slowing revenue growth. Meeting these challenges will require federal and provincial governments to work together, openly and honestly, to find solutions that will stand the test of time.

The fall federal budget is a good place to start – not just with short-term measures, but with a clear plan for the decade ahead. The sooner we begin, the better our chances of getting it right.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary and the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

Want more insights like this? Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest research and expert commentary.

Related Publications

- Opinions & Editorials

- Research