Home / Publications / Research / Pruning the Rulebook: Canada’s Financial Regulatory Scorecard, Year Two

- Media Releases

- Research

- |

Pruning the Rulebook: Canada’s Financial Regulatory Scorecard, Year Two

Summary:

| Citation | Gherardo Caracciolo. 2025. "Pruning the Rulebook: Canada’s Financial Regulatory Scorecard, Year Two." Verbatim. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Pruning the Rulebook: Canada’s Financial Regulatory Scorecard, Year Two – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Pruning the Rulebook: Canada’s Financial Regulatory Scorecard, Year Two |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/pruning-the-rulebook-canadas-financial-regulatory-scorecard-year-two/ |

| Published Date: | October 16, 2025 |

| Accessed Date: | December 3, 2025 |

Outline

Outline

Related Topics

Press Release

Files

For all media inquiries, including requests for reports or interviews:

- In the second year of our regulatory scorecard paper, results continue to show the need for a more balanced approach to financial oversight, one that explicitly incorporates innovation and competition alongside traditional stability and consumer protection goals. Newly issued and updated regulatory documents did not change previous results.

- The imbalance reflects the mandates of Canadian regulators, which stand in contrast to those of their UK, Australian, and US peers, where innovation and competition are more explicitly recognized.

- The study highlights deficiencies in the implementation and communication of cost-benefit analyses. Compliance costs are increasingly embedded across most of the financial sector workforce, with the share of labour costs and revenues devoted to compliance rising steadily, significantly exceeding international counterparts, and falling disproportionately on smaller firms.

- If left unaddressed, these asymmetric and rising compliance costs risk diverting skilled labour and capital away from core business functions, undermining productivity, innovation, and the overall competitiveness of Canada’s financial sector.

- Modernizing the mandates of Canadian regulators to explicitly recognize the tradeoffs between stability, investor protection, and economic dynamism is an economic imperative.

1. Introduction

Canada continues to face a well-documented struggle with weak productivity growth, poor business investment, and sluggish economic expansion.11 See: Robson and Bafale (2024) and Eichenbaum, Alexopoulos, and Kronick (2024), among others. There is also a quantifiable link in Canada between growing regulatory burdens, including financial sector regulation and weaker growth.22 See, for example, Gu (2025). The challenge, therefore, is not whether to regulate, but how: regulators must find a balance between safeguarding financial stability and enabling economic dynamism. Achieving such a balance could be especially consequential in Canada, where both growth and competitiveness remain fragile.

Against this backdrop, a crucial question is whether Canadian financial regulators operate within a sound and structured framework that ensures the implementation of truly necessary rules and regulations. To provide an answer, this paper builds on the work of Bourque and Caracciolo (2024)33 To view last year’s report, see: Bourque, Paul C., and Gherardo Gennaro Caracciolo. 2024. The Good, the Bad and the Unnecessary: A Scorecard for Financial Regulations in Canada. Commentary 664. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. July. https://cdhowe.org/publication/good-bad-and-unnecessary-scorecard-financial-regulations-canada/. which employed two complementary types of analysis – one theoretical, one empirical – to shed light on the strengths and the weaknesses of Canada’s regulatory landscape.

The theoretical analysis established the foundation for evaluating regulatory effectiveness by defining the core principles that should guide financial regulators in building a sound and efficient regulatory framework.44 In line with the ones defined by the OECD. It identified three essential steps that should underpin any regulation-making process: (1) thoroughly identifying the problem; (2) conducting a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis to weigh the implications of potential regulations; and (3) clearly articulating objectives to ensure predictability and consistency.

The empirical analysis involved a two-stage quantitative and qualitative textual analysis. The first stage consisted of an international comparison, where the performance of Canada’s primary federal financial regulator – the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) – was benchmarked against two international counterparts: the United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). This comparative analysis helped contextualize OSFI’s regulatory approach in relation to best practices observed in other financially comparable jurisdictions.

The second stage dug deeper into the Canadian financial regulatory landscape, evaluating the regulations of the main federal and provincial bodies against the principles identified in the theoretical framework. To do this, Bourque and Caracciolo (2024) developed a comprehensive scorecard that assessed core regulatory documents to determine the extent to which Canadian regulators adhered to these principles.

The findings showed that although Canadian regulators have generally succeeded in crafting well-structured regulations, their approach often falls short of adhering – on aggregate – to the core principles outlined in the framework. This leads to a lack of predictability and a more reactive, rather than proactive, set of rules and regulations. In this environment, rules are introduced in response to emerging challenges rather than through proactive, forward-looking planning. Further, there is a notable lack of systematic and substantive use of cost-benefit analysis, both in the development of regulations and in communicating their expected impact.

The scorecard allowed for an investigation into the priorities of Canadian regulators. Most of the current regulations in Canada place financial stability and consumer protection as their primary goals. These are, of course, both crucial objectives; however, they are too often pursued without adequate consideration of their interplay with innovation and competition. As a result, regulatory frameworks may end up stifling growth, particularly among smaller firms that lack the resources to absorb compliance costs as easily as larger institutions.

Building on last year’s study, this paper has three principal objectives. First, it updates the regulatory scorecard. An annual update makes it possible to track how Canadian regulatory priorities evolve over time and assess whether any progress is being made in addressing the shortcomings identified earlier. Notably, this updated scorecard reveals that the fundamental orientation of Canadian financial regulation remains largely unchanged: stability and consumer protection continue to dominate (if anything, with a slight uptick), while considerations of dynamism, innovation, and competition remain on the back burner. To be sure, some rebalancing is emerging. Ad hoc initiatives – such as blanket orders, sandbox activities, and similar discretionary measures – have introduced some pockets of innovation and efforts to reduce administrative burden. Nevertheless, our main point persists: without a deeper shift in regulatory philosophy, such measures risk remaining isolated exceptions, rather than indicative of a broader shift.

To probe the core of Canadian regulators’ philosophy – and to test whether the observed regulatory imbalance is structural – the analysis is extended to include foundational documents that set out regulators’ objectives, mandates, and missions.55 We examine the mandates and mission of Canadian financial regulators (including both prudential and securities regulators). Examining these texts allows for an assessment as to whether the current priorities are rooted in the very design and self-perception of regulatory institutions, rather than from recent or temporary policy choices. The results show a clear hierarchy of objectives in regulator mandates across the country, with stability and consumer protection firmly dominant. This stands in contrast to the mandates of regulators in the UK, Australia, and the US, where innovation and competition feature more prominently. Without a shift toward a more balanced regulatory philosophy, Canada risks falling further behind in competitiveness, innovation-driven growth, and overall economic resilience.

One consequence of this regulatory imbalance is the potential for disproportionate compliance costs – relative to benefits – being imposed on the financial sector. Hence, the third goal of the paper is to evaluate the cost side of cost-benefit analysis in regulatory decision-making. We do this by quantifying and identifying compliance costs imposed by financial regulations across different financial subsectors, with particular attention to varying firm sizes. By empirically assessing these costs, this study fills a critical gap in the literature, offering concrete evidence of how current regulatory frameworks affect businesses, especially smaller firms that may face a heavier burden. Our aim is to start a new, thorough, and reliable database that will create valuable insights for policymakers and regulators.

The first wave of results is concerning. Although the benefits of regulation are difficult to measure, compliance duties are becoming increasingly embedded across most of the financial sector workforce. The share of labour and revenues devoted to compliance continues to rise – well above international counterparts – and the burden falls disproportionately on smaller firms. If left unaddressed, these asymmetric and rising compliance costs risk diverting skilled labour and capital away from core business functions, further undermining productivity, innovation, and the overall competitiveness of Canada’s financial sector.

2. The Updated Scorecard

2.1 Methodology

To update the regulatory scorecard, we employ the same textual and topic analysis framework as in the previous study (Bourque and Caracciolo 2024), applying it to newly issued and updated regulatory documents from the past year (June 2024 to June 2025) alongside previous documents. Our focus remains on key regulatory materials across the banking, insurance, pensions, and securities sectors, including Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario (FSRA) Guidelines, Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) Guidelines, Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions’ (OSFI) Guideline Impact Analysis (and related documents), and Canadian Securities Administrators’ (CSA) Companion Policies.66 See Bourque and Caracciolo (2024) for a thorough discussion regarding the choice of documents.

Using natural language processing (NLP) techniques (see Bourque and Caracciolo [2024] for a more complete description), we extract and classify key terms, sentences, and logical arguments to assess how these documents address market failures (e.g., market abuse, asymmetric information, systemic and liquidity risk), policy objectives (e.g., stability, transparency, efficiency), and cost-benefit considerations.77 Regarding CSA documents: references to cost-benefit analysis can be found in some national instruments and consultations. However, in our view, such references are not sufficiently substantive, nor connected enough to the broader regulatory narrative contained in the Companion Policies. This allows us to evaluate the extent to which Canadian regulators align with the core principles of sound regulatory decision-making: problem identification, cost-benefit assessment, and clear articulation of objectives.

While the core methodology remains unchanged, this iteration refines our classification process.88 Some older guidelines have been updated, and so we reanalyzed them. We will perform this update on an annual basis, allowing us to systematically track shifts in regulatory priorities over time. The full updated scorecard, which reflects these refinements and new findings, is presented in online Appendix C (Table 1).

2.2 Results

This updated regulatory scorecard reveals similar results as last year in Canadian financial regulation: the fundamental priorities of regulatory authorities have remained largely unchanged, with consumer protection, transparency, and stability dominating the regulatory agenda. Despite ongoing discussions about the need to stimulate economic growth in Canada, our analysis indicates that a more balanced approach to financial oversight, one that explicitly incorporates innovation and competition alongside these traditional goals, remains largely absent from newly issued and updated regulatory documents (evaluated alongside existing documents).

Most regulatory initiatives (approximately 92 percent versus 89 percent of last year) primarily target market abuse, stability, transparency, and, ultimately, improved consumer protection. On the other hand, a smaller fraction (around 14 percent, compared to 16 percent last year) explicitly aim to enhance efficiency, promote growth and innovation, and take into account the stability versus dynamism trade-off that is a critical part of any regulatory structure.

One notable exception among the newly analyzed documents is delivered by FSRA’s Guideline GR0014APP, which demonstrates a departure from the prevailing regulatory narrative. This document explicitly acknowledges the importance of fostering a more dynamic financial marketplace, introducing measures aimed at reducing barriers to entry and enhancing the competitive landscape.99 This lines up with FSRA’s broader push towards a more principles-based approach to regulation, which is definitely a step in the direction suggested by this (and the previous) paper. We also acknowledge that CSA’s National Instrument 81-101 Mutual Fund Prospectus Disclosure, which focuses on enhancing transparency and investor protection through standardized disclosure requirements, aims to simplify the disclosure procedure and, therefore, represents an important step forward in regulatory efficiency.

Beyond these individual measures, we note that FSRA and CSA have also set out broader ambitions. FSRA’s 2024–2027 Strategic Plan highlights burden reduction and regulatory efficiency, while CSA’s 2025–2028 Business Plan emphasizes internationally competitive markets and regulatory approaches that adapt to innovation and technological change. These commitments are commendable and encouraging, but they remain largely aspirational: they signal intent, but the challenge is whether they will translate into consistent features of day-to-day regulatory instruments. Our annual updated scorecard will be able to monitor this.

Breaking down our analysis to the single regulator level, FSRA stands out as the one that has gone furthest in bridging the gap between intentions and actions: around 17 percent of its analyzed documents now contain growth or innovation considerations (up from 13 percent last year). By contrast, CSA – which admittedly had the highest percentage last year – OSFI, and AMF remain closer to their prior levels, with innovation-oriented content in only 18 percent, 10 percent, and 10 percent of their documents, respectively. For now, the broader regulatory environment continues to disproportionately prioritize risk mitigation and consumer safeguards over fostering a more adaptive and competitive financial sector.

Moreover, and again consistent with last year, there is a dearth of explicit cost-benefit analysis or meaningful discussion of the broader economic costs imposed by the regulatory interventions across nearly all examined documents.1010 As highlighted in the first iteration of the paper, we acknowledge that the OSC and FSRA are the only regulators legally required to conduct a cost-benefit analysis whenever they amend or implement a new rule, which they do. Our argument is around the substance of these analyses and their connection to the foundational documents and communication with the public.

3. Where Does This Imbalance Come From?

Our scorecard raises a fundamental question: is this imbalance an unintentional result, or does it reflect the regulators’ mandate and therefore a structural feature of Canada’s regulatory landscape? To answer this, we examined the mandates and missions of Canadian financial regulators (prudential and securities regulators alike). For the vast majority, dynamism, competition, and capital formation are typically only included following the mission statements – OSC being a notable exception. The primary focus of the mission statements remains on stability, investor protection, and market integrity, which are vital but fall short of capturing the full potential of a dynamic, innovative financial sector.

For example, OSFI’s mandate is to:

- “ensure federally regulated financial institutions (FRFIs) and federally regulated pension plans (FRPPs) remain in sound financial condition;

- ensure FRFIs protect themselves against threats to their integrity and security, including foreign interference;

- act early when issues arise and require FRFIs and FRPPs to take necessary corrective measures without delay;

- monitor and evaluate risks and promote sound risk management by FRFIs and FRPPs.”1111 OSFI. 2024. “The OSFI Story.” March 25. https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/en/about-osfi/osfi-story.

It is only after that that they say, “In exercising our mandate:

- for FRFIs, we strive to protect the rights and interests of depositors, policyholders and financial institution creditors while having due regard for the need to allow FRFIs to compete effectively and take reasonable risks.”

To further substantiate this point, we look to see whether the secondary status of competition, cost, and innovation in Canadian regulators’ mandates is a uniquely Canadian phenomenon or part of a broader international pattern. Benchmarking against international best practices is particularly relevant in financial regulation, where peer jurisdictions face similar market dynamics and policy tradeoffs. By comparing Canada’s regulatory mandates to those of similar international counterparts, we can better assess whether the Canadian approach reflects a deliberate policy choice or a missed opportunity to align with evolving global standards.

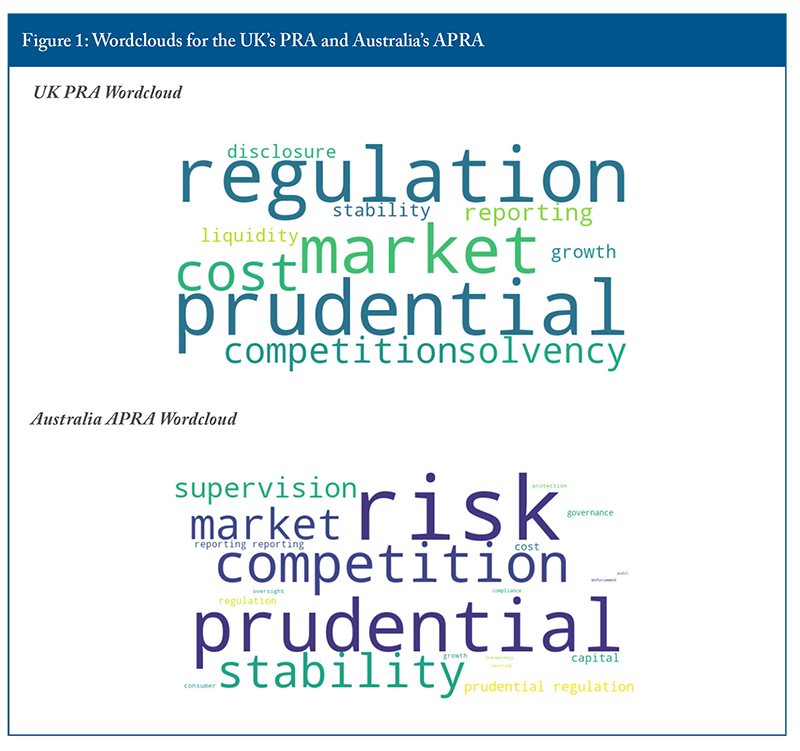

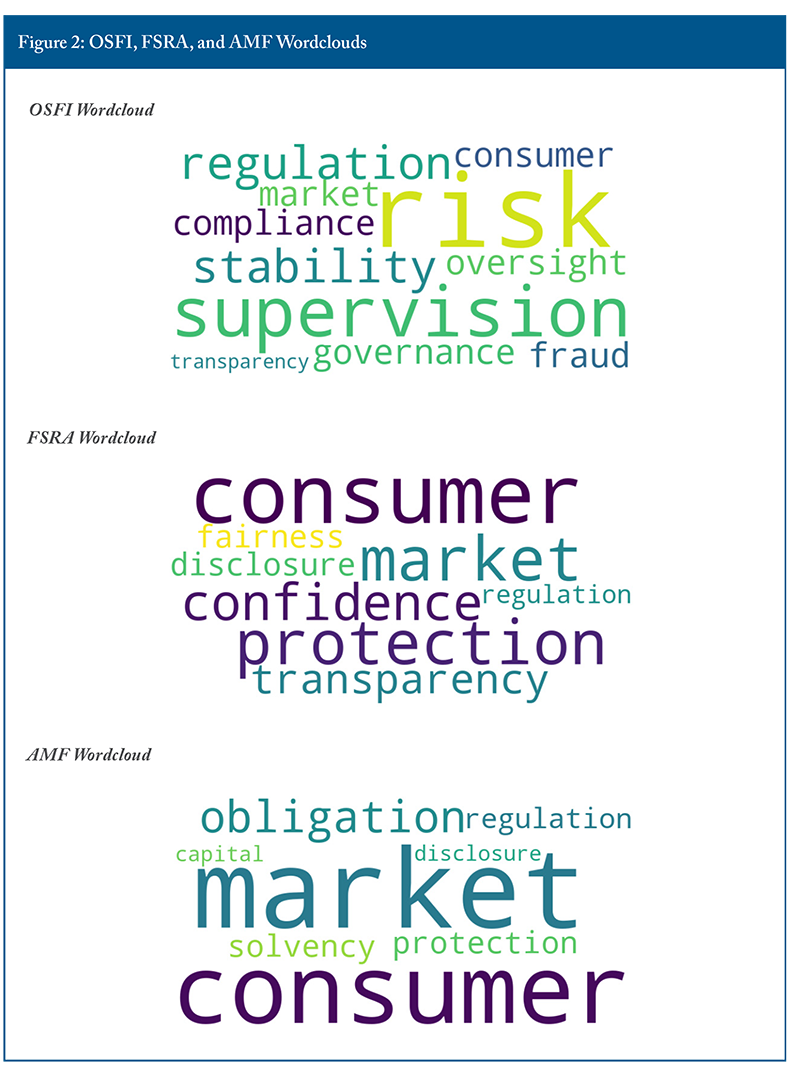

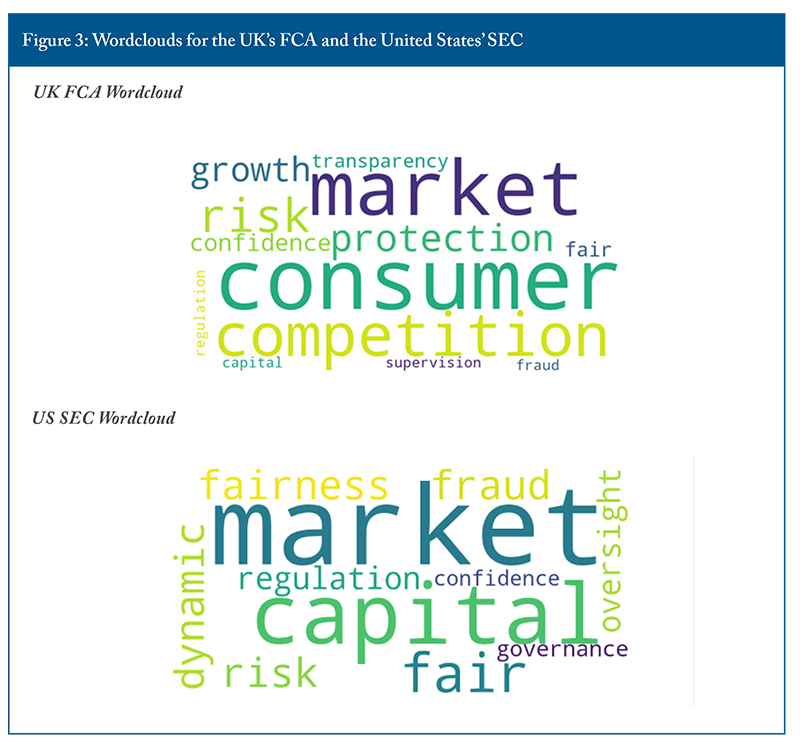

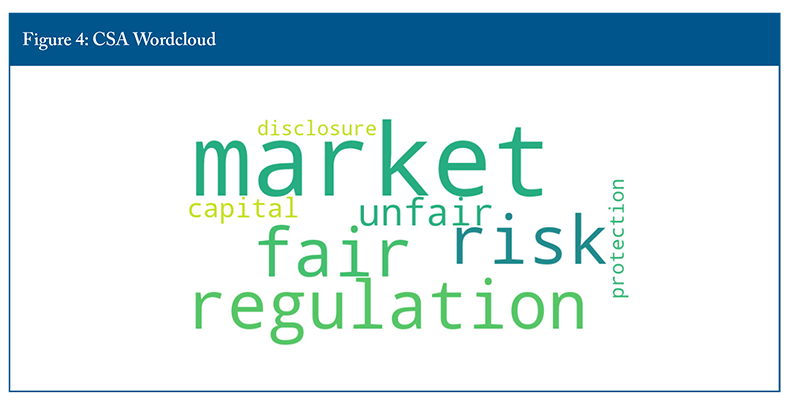

As in the scorecard, we conducted a systematic textual analysis of the mandates and missions of major financial regulators in Canada, the UK,1212 Bank of England. 2025. “Our Secondary Objectives.” July 16. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/secondary-competition-objective?utm_; Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). 2025. “Promoting Competition.” March 25. https://www.fca.org.uk/about/what-we-do/promoting-competition. Australia,1313 Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). 2025. “Who We Are.” https://www.apra.gov.au/who-we-are. and the United States.1414 US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2025. “About.” January 23. https://www.sec.gov/about. Using natural language processing techniques, we extracted and quantified the most prominent themes and keywords in these foundational documents.1515 We apply systematic natural language processing (NLP) techniques to the mandates and mission statements, including text preprocessing, tokenization, and frequency analysis of significant terms. The resulting term prominence is visualized as a word cloud to provide an intuitive summary of key themes in these foundational documents. This approach builds on standard text mining methodologies widely used in qualitative content analysis. The results are visually summarized in the accompanying wordclouds. The size of each word reflects its frequency and “keyness” – a measure of statistical importance and relevance within the analyzed texts. Unlike simple term frequency, this approach highlights the concepts and priorities regulators emphasize disproportionately relative to the overall corpus, providing a more nuanced quantitative assessment. The wordclouds thus offer an intuitive visual snapshot of the dominant regulatory themes.

What emerges from this analysis is a clear divergence in regulatory philosophy. The wordclouds for the UK and Australia show that terms such as “competition,” “growth,” and “cost” are extremely relevant in the language of their regulators’ mandates. This reflects an explicit and deliberate embedding of economic dynamism and efficiency into their regulatory objectives.

Indeed, the UK’s PRA and Australia’s APRA, while maintaining stability and consumer protection as core priorities, have made efforts to explicitly incorporate competition, innovation, and market adaptability into their mandates over the past decade (Figure 1). The PRA, for example, makes the case that long-term resilience requires a financial sector that is not only stable but also competitive, forward-looking, dynamic, and innovative. By integrating efficiency and market innovation, the PRA looks to ensure that the financial ecosystem can grow and evolve with emerging market demands.

Similarly, APRA’s mandate balances the primary objective of safety “with considerations of competition, efficiency, contestability (making barriers to entry high enough to protect consumers but not so high that they unnecessarily hinder competition) and competitive neutrality (ensuring that private and public sector businesses compete on a level playing field).”1616 APRA. 2025. “Who We Are.” https://www.apra.gov.au/who-we-are.

In contrast, the wordclouds for Canadian deposit-taking and insurance regulators reveal a notable absence of such language (see Figure 2 for OSFI, FSRA1717 Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario (FSRA). 2025. “About FSRA.” June 30. https://www.fsrao.ca/about-fsra., and AMF1818 Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF). 2025. “Mission.” https://lautorite.qc.ca/en/general-public/about-the-amf/mission.). Their mandates and mission, while perhaps containing references to competition and growth, are dominated by terms like “stability,” “solvency,” “obligation,” and “consumer protection.”

This linguistic gap is not just cosmetic; it reflects a structural difference in regulatory philosophy. Without a formal mandate to consider competition or cost, many Canadian regulators have less incentive to systematically integrate these factors into their rulemaking.

A similar divergence is evident in securities regulation. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) place competition, growth, dynamism, and capital formation at the centre of their regulatory mandates (Figure 3).1919 FCA. 2025. “Promoting Competition.” March 25. https://www.fca.org.uk/about/what-we-do/promoting-competition; SEC. 2025. “About.” January 23. https://www.sec.gov/about.

These are not just theoretical differences. SEC’s statutory responsibility to facilitate capital formation led to a practical framework that drives policies to increase market access for a broader range of firms. The SEC has introduced initiatives such as Regulation A+ and crowdfunding exemptions, which aim to make it easier for small and emerging firms to raise capital while balancing investor protection. The FCA’s mandate similarly incorporates competition as a core principle, emphasizing measures to ensure that financial markets remain vibrant and responsive to technological progress, highlighting also how this, in turn, will increase investors’ welfare.

In contrast, although some of the largest securities commissions – such as the OSC, BCSC, and ASC – are notable exceptions, explicit competition or capital formation mandates are not necessarily the norm across our 13 provincial securities commissions, nor at the umbrella organization, the CSA (see Figure 4 for CSA’s wordcloud).2020 CSA. 2025. “Our Mission.” https://www.securities-administrators.ca/about/who-we-are/our-mission/. The Ontario government did take a step in this direction in 2021, when it expanded the OSC’s mandate to include fostering capital formation and competition.

While investor protection and market integrity remain fundamental and essential objectives, the absence of a consistently clear directive to foster market dynamism means that regulatory actions are more likely to be slanted towards a more cautious, conservative approach. There have certainly been some targeted efforts to support innovation and broaden access to capital, such as the CSA’s Financial Innovation Hub2121 CSA. 2025. “CSA Financial Innovation Hub.” https://www.securities-administrators.ca/csa-activities/csa-finhub/. and their harmonized crowdfunding rules, but these remain isolated and ad hoc. Unlike the systematic, mandate-driven commitment seen in the UK and the United States, Canadian initiatives are not consistently rooted in a formal regulatory priority to promote capital formation.

This regulatory gap is particularly concerning given Canada’s persistent struggles with weak productivity growth, poor investment, sluggish economic expansion, and relatively low levels of innovation adoption.2222 See: Robson and Bafale (2024) and Eichenbaum, Alexopoulos, and Kronick (2024), among others. A financial regulatory environment that does not explicitly encourage competition, innovation, and capital formation may reinforce these trends by raising barriers to entry, increasing compliance costs for smaller firms, and discouraging capital market participation, particularly from high-potential startups and emerging sectors. The absence of a statutory capital formation mandate within securities regulation means that new firms seeking to grow or disrupt established industries may face challenges in accessing the funding they need, further contributing to a stagnant market environment.

Modernizing the mandates of Canadian regulators to explicitly recognize the tradeoffs between stability, investor protection, and economic dynamism is an economic imperative. Without a shift toward a more balanced regulatory philosophy, Canada risks falling further behind in capital market competitiveness, innovation-driven growth, and overall economic resilience. Financial stability does not have to come at the expense of progress, and as other international regulators are trying to do, we should aim to achieve the best-designed regulatory framework in order to foster both stability and market growth. A more forward-looking mandate, in which competition, capital formation, and innovation are treated as integral to the health of the financial system, would not only strengthen Canada’s economic position but also ensure that its regulatory framework remains adaptable to future challenges and opportunities.

4. Neglected by Design: Quantifying the Costs of Regulation

A practical consequence of the imbalance in regulatory priorities are gaps in how cost-benefit analyses are designed and implemented in Canadian financial regulation. A further goal of this paper is to help push this issue ahead by developing a method for more accurately quantifying regulatory costs. The aim is to create a new, annually updated and survey-based cost database that provides a new lens on the regulatory burden and equips regulators with a tool to better understand the real impact of their activity across firms of different sizes and sectors. We acknowledge upfront that we focus specifically on the cost side of the analysis, leaving the benefits assessment to future work.

4.1 The Importance of Quantifying Regulatory Costs and the Difficulties Implied by the Task

The costs of regulations – across all industries, including financial services – are often cited as one of the biggest factors contributing to reduced market entry, increasing industry concentration, and weak investment. This pattern is evident worldwide, including in the United States and Canada (Gutiérrez and Philippon 2019, 2017), as well as in many other developed countries (Aghion et al. 2021). The mechanism postulated by the literature above is that compliance costs as a result of government regulations disproportionately impact small firms, creating barriers to new entrants, inhibiting business growth, and therefore ultimately slowing down productivity. Additionally, when large incumbents face increased regulatory costs, they either incur them, which may affect other parts of their business, or pass some of these costs on to consumers, especially if, given higher barriers, they end up possessing significant market power. As a result, consumers will also be adversely affected, which has broader implications for the overall economy.

The central issue remains the unresolved question of how to define and quantify the total compliance cost properly, as well as how to assess whether these costs affect small and large firms differently. Measuring compliance costs at the firm level is, in fact, a highly complex challenge from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives.

First, from a qualitative perspective, there is no unanimous agreement on which costs to include and how to model their impact on different firms. While some argue that the biggest part of compliance costs can be significantly decreased through economies of scale and lobbying, and therefore are much smaller for larger firms (Davis 2017; Alesina et al. 2018; Gutiérrez and Philippon 2019; Akcigit and Ates 2020; Aghion et al. 2021), others suggest that small businesses are, in fact, the ones in a better position, as they receive plenty of exemptions (Brock and Evans 1985; Aghion et al. 2021).2323 This debate is particularly relevant for Canada. For example, OSFI applies a strong proportional approach to its regulatory activity: small- and medium-sized deposit-taking institutions that face large incumbents benefit from simplified leverage and liquidity requirements, transitional arrangements under Basel III, and less onerous corporate governance expectations compared to large banks. These targeted measures are designed to reduce the compliance burden for smaller or less complex institutions, although the overall impact and accessibility of such exemptions remain unclear.

Second, from a quantitative perspective, measuring firm-specific regulatory burdens presents numerous obstacles. Quantifying firm-level compliance costs is complex due to limited granular data. Existing studies often focus on broad relationships or industry-level shocks (Gutiérrez and Philippon 2019), lacking detailed evaluations of individual business burdens. These obstacles include variations in regulatory requirements across financial subsectors, overlapping regulations from different government levels, tiered compliance rules, varying inspection stringency, and differing technological and efficiency constraints across firm sizes (Agarwal et al. 2014; Stiglitz 2009; Kang and Silveira 2021; Goff et al. 1996). As Goff et al. (1996) noted, “the measurement problems are so extensive that directly observing the total regulatory burden is practically impossible.”

4.2 Modelling and Measuring Compliance Cost and Its Impact on Labour Productivity: Traditional Methods and Our Approach

Traditional approaches to quantifying the regulatory burden typically fall into two broad categories: counting the number of regulations in force or measuring the size of compliance departments within firms.2424 For example, see: Restuccia et al. (2008); Trebbi et al. (2023). The first approach, despite its widespread use, is simplistic and can be misleading. It assumes that each new regulation automatically adds the same weight to firms’ compliance burdens, failing, therefore, to account for differences in complexity, enforcement, and actual economic impact. Most importantly, it also disregards the fact that not all regulatory documents impose additional costs. Some provide clarifications, interpretation, simplify compliance procedures, or consolidate existing rules, thereby reducing uncertainty and making it easier for businesses to adhere to legal requirements. A regulatory framework with an extensive set of well-organized, clearly written guidelines can be far easier to navigate than a system with fewer but ambiguous or conflicting regulations. Yet, a raw count of regulations makes no such distinctions, treating all rules as equally burdensome and limiting insights into the real costs faced by businesses.

The second common approach – measuring the size of compliance departments – is somewhat more informative but still incomplete. This method operates on the assumption that regulatory costs can be estimated by looking at the number of employees explicitly assigned to compliance roles.2525 See, for example, Trebbi et al. (2023). While this metric does offer a tangible measure of firms’ direct expenditures on compliance, it fails to capture the reality that regulatory obligations extend far beyond dedicated compliance teams. In practice, firms cannot limit compliance tasks to a single department; employees across multiple functions – including finance, operations, and even customer service – must allocate significant portions of their work to meeting particular regulatory requirements. These responsibilities often divert employees from their core business functions, increasing operational complexity and reducing efficiency in ways that are difficult to measure using traditional methods.

The failure to account for these indirect costs leads to a fundamental misrepresentation of how regulatory compliance affects firms, particularly with respect to labour productivity. Standard measures of productivity typically calculate output per worker, assuming that all employee time is dedicated to value-generating activities. However, when employees across departments must dedicate significant portions of their time to compliance, their effective contribution to production decreases even if they are not officially counted as part of the compliance workforce. This distortion is particularly relevant in highly regulated industries, such as the financial sector, where firms must continuously adapt to evolving rules, engage in periodic audits, and maintain detailed reporting practices. These obligations consume work hours that could otherwise be devoted to innovation, strategic growth, or client service. By failing to account for these hidden labour costs, traditional approaches systematically underestimate the true economic impact of regulatory compliance.

Evidence in support of this argument comes from occupational data sources such as the US O*NET database, which provides firm-level insights into job responsibilities at the single-employee level across industries. These data reveal that compliance-related tasks affect, to different extents, most of the workers, and are not confined to designated regulatory personnel.2626 Trebbi et al. (2023) show that regulation-related occupations span about one-third of all occupation categories, covering not only compliance officers, but also compensation and benefits managers, financial examiners, insurance policy processing clerks, technicians, and many others.

A more accurate framework for assessing regulatory costs must therefore go beyond these limited proxies and capture the full extent of compliance-related labour reallocation. This is precisely what we try to accomplish with our project. Through detailed firm-level surveys, we collect data not only on compliance department size but also on how regulatory responsibilities are distributed across the entire workforce. By distinguishing between employees who are fully dedicated to compliance and those who must allocate a portion of their time to regulatory tasks, we can develop a more precise estimate of how compliance demands affect firms’ overall labour productivity and financial performance. Our approach, which we call the Compliance Labour Cost Index, allows us to measure variation in regulatory costs across firms of different sizes and financial subsectors, helping to assess whether burdens are proportionate or not.2727 Details of traditional modelling techniques and of our proposed variation can be found in online Appendix A.

Furthermore, our survey methodology captures the evolution of compliance intensity over time. This paper presents the first wave of our survey, with our long-term goal being to conduct it every year, thereby creating a dynamic, up-to-date resource for understanding regulatory costs. By maintaining a consistent, structured approach to data collection, we will be able to track changes in compliance burdens over time, offering insights into whether new regulations are increasing costs, whether firms are finding more efficient ways to comply, and how regulatory expenses vary across different business models. This database will provide a clearer picture of regulatory costs at the firm level and also equip policymakers with the empirical evidence necessary to design smarter, more effective regulations – ones that balance economic growth with necessary oversight.

4.3 Survey Results

2828 Survey structure with questions and table reporting raw summary statistics can be found in online Appendix B.

The results presented here are based on an unbalanced panel2929 An unbalanced panel is a dataset in which different entities (55 firms) are observed for different numbers of time periods: in this case, not all firms provided data for all three fiscal years. of survey responses covering three fiscal years: 2019, 2023, and 2024.3030 Summary statistics will be available online and constantly updated as new results come in. This structure allows us to capture both pre- and post-pandemic conditions while filtering out the most acute COVID-19-related distortions in 2020, 2021, and 2022. The panel includes firms of varying sizes across the different subsectors of the Canadian financial sector, enabling both an aggregate view and size-based comparisons. The key findings from this survey can be grouped into four main observations, each highlighting a distinct aspect of the compliance burden.

Fact 1: Compliance is Everyone’s Job!

Compliance work is now deeply embedded across the financial sector workforce. In 2024, on average, 73 percent of employees had at least some compliance-related duties, and close to 8 percent spent the majority of their time (75–100 percent) on such tasks. As postulated in the previous sections, regulatory obligations are not confined to specialist compliance teams but are interwoven into the daily operations of most departments, diverting time and focus away from activities that directly generate value for clients or shareholders. The pervasiveness of compliance roles means that regulation is no longer something handled at the margins of the business, but rather a constant presence shaping workflows across the organization.

Fact 2: Compliance Is Eating Payroll – A Growing Regulatory Burden Is Reshaping Workforce Allocation

The share of total labour costs devoted to compliance-related activities (time and salaries spent meeting regulatory requirements rather than delivering core products or services) has been rising steadily. Our Compliance Labour Cost Index stood at approximately 16 percent in 2019, rose to around 19 percent in 2023, and reached 22 percent in 2024. To put it differently, around one dollar in every five spent on payroll is now directed to tasks that exist solely to ensure regulatory adherence. To put these figures in context, Trebbi et al. (2023), using US establishment-level O*NET data, estimate that regulatory compliance accounts for 2.3 percent to 2.7 percent of total labour costs across the US financial sector. This divergence highlights the crucial need for a more systematic cost-benefit approach in Canadian regulatory design. We simply cannot afford such a big gap.3131 We acknowledge that US firms likely face significantly higher external compliance costs (e.g. due to litigation, enforcement risks, etc.) than in Canada. We talk about those next for Canada, but to the best of our knowledge, there is no study that would allow for a robust quantitative comparison of these external dimensions with the United States. We believe, however, that the size of the internal gap is likely not made up for by the opposite external gap.

Fact 3: External Compliance Costs Are Also Surging, and Are Eating into Revenues

While internal labour costs capture the human effort behind compliance, they tell only part of the story. A significant (and growing) portion of the regulatory burden is channelled through external spending: advisory fees, legal fees, compliance technologies, governance structures, and membership dues. These costs are less visible but no less impactful, directly affecting firms’ bottom lines and reducing their strategic flexibility. To gauge both their scale and their evolution over time, we measure external compliance costs as a share of total revenues. We can observe how this ratio has risen steadily over the three years analyzed, climbing from about 1.2 percent in 2019 to 1.6 percent in 2024. The increase reinforces how compliance imposes a mounting financial strain beyond internal labour, diverting resources that could otherwise be invested in innovation, growth, and other productive initiatives.

Fact 4: Size Matters (a Lot!) – The Compliance Burden Hits Small Firms Hardest

A striking asymmetry emerges between small firms (under 100 employees) and large firms (over 100 employees).3232 We lump Statistics Canada’s definition of medium- and large-sized firms into “large firms” with more than 100 employees. While the growth rate of compliance involvement and costs appears independent of firm size, their magnitude is not. In both 2023 and 2024, an average of 35 percent of workers in small firms had high or medium compliance involvement, compared with just 13 percent in larger ones.

As a natural consequence, smaller institutions shoulder significantly higher compliance costs: in 2024, the labour cost index reached 20 percent for small firms, compared with 12 percent for larger ones.

This imbalance is particularly worrying when we consider that small firms and startups are often the main engines of innovation, and as they grow, of productivity growth as well. Yet, these seem to be precisely the firms disproportionately drained by regulatory demands, risking a throttling effect on the dynamism and competitiveness of the entire financial sector.

In short, these facts require attention. Reassessing compliance costs must be an urgent priority on the regulators’ agenda, as it is essential to ensure the health and resilience of our financial sector.

5. Policy Discussion and Conclusion

The updated regulatory scorecard confirms that the core patterns identified in prior analysis persist. Canadian financial regulation continues to focus overwhelmingly on stability and consumer protection, while innovation, competition, and cost-efficiency remain secondary. This regulatory orientation is not just a product of recent policy inertia; it is deeply rooted in the structural design of mandates and institutional priorities. Current mandates apply a lexicographic hierarchy that prioritizes financial stability and consumer safeguards above all else – often at the expense of reducing unnecessary regulatory burdens and fostering economic dynamism and growth.

This imbalance is set to become an even greater challenge amid profound global shifts. Political instability in the United States, ongoing conflicts, and broader geopolitical tensions have created a more volatile and unpredictable environment. Stability will remain crucial, but Canada also has an opportunity to adopt regulatory frameworks that actively promote efficiency, innovation, and growth. With such elements in place, Canadian financial institutions can better thrive in a changing world while reinforcing the very stability regulators aim to safeguard.

The costs of the current imbalance are already evident. Evidence shows that compliance burdens are rising sharply, with significant implications for firms’ competitiveness. Our Compliance Labour Cost Index, which tracks regulatory labour across the sector, reveals that compliance demands grew from 16 percent of total internal labour in 2019 to 21 percent in 2024. The strain is particularly acute for smaller firms, where compliance costs reached 28 percent of payroll – double the share borne by larger institutions. External compliance expenses, including advisory, technology, and governance costs, have also grown, further restricting firms’ ability to invest in growth and innovation.

These findings show that stability-focused regulation, absent economic balance, can erode productivity, innovation, and long-term market vitality. Smaller firms are particularly vulnerable, even though they are central drivers of competition and innovation. Policy responses should therefore focus on two priorities.

First, regulatory mandates must be modernized to recognize the full set of policy objectives: stability, investor protection, efficiency, growth, and competition. Explicitly embedding economic goals alongside traditional safeguards would bring Canadian practice closer to international standards and create a more adaptive framework. Encouragingly, securities regulators in Ontario, BC, and Alberta, as well as Ontario’s provincial prudential regulator, FSRA, have already begun acknowledging this need in business plans that emphasize competitiveness and in guidelines aimed at reducing regulatory burden. Our scorecard will continue to track whether such commitments translate into practice.

Second, regulatory design should always require rigorous cost-benefit analyses that are made publicly available at the outset of rulemaking. Transparent, upfront cost-benefit analyses would establish clear benchmarks against which post-implementation reviews can be meaningfully conducted. Tools such as our Compliance Labour Cost Index can enrich this process of comparison. Institutionalizing public cost-benefit analyses would ensure that regulations are evaluated not only against their intended goals but also against their real-world economic costs, enabling more proportionate and adaptive policymaking.

In sum, safeguarding stability and protecting consumers remain essential. But stability itself increasingly depends on Canada’s ability to sustain competitive, innovative, and efficient financial markets.

The author extends gratitude to Pragya Anand, Angélique Bernabé, Ian Bragg, Jeff Guthrie, Sarah Hobbs, Jeremy Kronick, Peter MacKenzie, Grant Vingoe, Mark Zelmer, Tingting Zhang, and several anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. The author retains responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, Sumit, David Lucca, Amit Seru, and Francesco Trebbi. 2014. “Inconsistent Regulators: Evidence from Banking.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2): 889–938.

Aghion, Philippe, Antonin Bergeaud, Timo Boppart, Peter J. Klenow, and Huiyu Li. 2019. “Missing Growth from Creative Destruction.” American Economic Review 109(8): 2795–2822.

Akcigit, Ufuk, and Sina T. Ates. 2020. “Ten Facts on Declining Business Dynamism and Lessons from Endogenous Growth Theory.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 13(1): 257–298.

Alesina, Alberto, Carlo A. Favero, and Francesco Giavazzi. 2018. “What Do We Know about the Effects of Austerity?” American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 108: 524–530.

Bourque, Paul C., and Gherardo Gennaro Caracciolo. 2024. The Good, the Bad and the Unnecessary: A Scorecard for Financial Regulations in Canada. Commentary 664. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. July. https://cdhowe.org/publication/good-bad-and-unnecessary-scorecard-financial-regulations-canada/.

Brock, William A., and David S. Evans. 1985. The Economics of Small Businesses: Their Role and Regulation in the U.S. Economy. New York: Holmes & Meier.

Davis, Steven J. 2017. “Regulatory Complexity and Policy Uncertainty: Headwinds of Our Own Making.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall): 301–375.

Eichenbaum, Martin, Michelle Alexopoulos, and Jeremy Kronick. 2024. “Economists Must Convince the Public That Productivity Isn’t Just a Number.” The Globe and Mail. August 5. https://cdhowe.org/publication/eichenbaum-alexopoulos-kronick-economists-must-convince-public-productivity-isnt-just/.

Goff, Brian L., et al. 1996. Regulation and Macroeconomic Performance. Vol. 21. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Gu, Wulong. 2025. “Regulatory Accumulation, Business Dynamism and Economic Growth in Canada.” Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 481. Statistics Canada. February 10. https://doi.org/10.25318/11f0019m2025002-eng.

Gutiérrez, Germán, and Thomas Philippon. 2017. “Declining Competition and Investment in the U.S.” NBER Working Paper No. 23583. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23583.

_______________. 2019. “The Failure of Free Entry.” NBER Working Paper No. 26001.

Kang, Karam, and Bernardo S. Silveira. 2021. “Understanding Disparities in Punishment: Regulator Preferences and Expertise.” Journal of Political Economy 129(10): 2947–2992.

Restuccia, Diego, and Richard Rogerson. 2008. “Policy Distortions and Aggregate Productivity with Heterogeneous Establishments.” Review of Economic Dynamics 11(4): 707–720.

Robson, William B.P., and Mawakina Bafale. 2024. Underequipped: How Weak Capital Investment Hurts Canadian Prosperity and What to Do about It. Commentary 666. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. September. https://cdhowe.org/publication/underequipped-how-weak-capital-investment-hurts-canadian-prosperity-and-what/.

Stiglitz, Joseph. 2009. “Regulation and Failure.” In New Perspectives on Regulation, edited by David Moss and John Cisternino, 11–23. Cambridge, MA: The Tobin Project.

Trebbi, Francesco, Miao Ben Zhang, and Michael Simkovic. 2023. “The Cost of Regulatory Compliance in the United States.” USC Marshall School of Business Research Paper. January 15. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4331146.

Related Publications

- Intelligence Memos