Home / Publications / Research / Friend or Foe? Preferred Pharmacy Networks and the Future of Drug Benefits in Canada

- Research

- |

Friend or Foe? Preferred Pharmacy Networks and the Future of Drug Benefits in Canada

Summary:

| Citation | Paul Grootendorst. 2025. "Friend or Foe? Preferred Pharmacy Networks and the Future of Drug Benefits in Canada." ###. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. |

| Page Title: | Friend or Foe? Preferred Pharmacy Networks and the Future of Drug Benefits in Canada – C.D. Howe Institute |

| Article Title: | Friend or Foe? Preferred Pharmacy Networks and the Future of Drug Benefits in Canada |

| URL: | https://cdhowe.org/publication/friend-or-foe-preferred-pharmacy-networks-and-the-future-of-drug-benefits-in-canada/ |

| Published Date: | August 21, 2025 |

| Accessed Date: | January 31, 2026 |

Outline

Outline

Authors

Related Topics

Press Release

Files

For all media inquiries, including requests for reports or interviews:

by Paul Grootendorst

- Preferred Pharmacy Networks (PPNs) in Canada are primarily used for distributing high-cost specialty drugs through select pharmacies that agree to lower fees in exchange for higher volumes. While some have suggested that PPNs increase market concentration, there is limited evidence of widespread harm to small and independent pharmacies.

- Pharmacy stakeholders have cautioned that the use of PPNs is the latest example of an evolution of Canada’s drug benefits system towards the US model. However, Canada’s system is structurally different, making a drift toward the dysfunctions of the US model unlikely. The main differences include less vertical integration and federal drug price regulation. The result is much higher levels of reimbursement to community pharmacies in Canada than in the United States.

- Given the limited savings available and drug plan beneficiary preferences for pharmacy choice, it is unlikely that PPNs will expand beyond specialty drugs. Bans on PPNs are not supported by current evidence, though further monitoring of pharmacy market concentration is warranted.

- While some have raised concerns that PPNs fragment patient care, there is limited evidence of widespread harm to patients. Nevertheless, pharmacy regulators may wish to assess information-sharing requirements between specialty pharmacies and out-of-network pharmacies. Insurers may wish to assess drug plan sponsors’ willingness to pay for PPNs that allow more pharmacies to participate.

Introduction

All private drug insurers in Canada have introduced “preferred pharmacy networks,” or PPNs.11 Hannay, Chris, Susan Krashinsky Robertson, and Clare O’Hara. 2025. “Exclusive Deals Between Insurance Companies and Pharmacies Becoming More Prevalent in Canada.” The Globe and Mail. January 21. https://archive.ph/veRth. PPN member pharmacies agree to charge insurers discounted fees and provide ancillary supports for patients taking certain medications. The insurer, in return, encourages its beneficiaries to attend a PPN member pharmacy. The insurer does so by charging beneficiaries lower copays for services received from a PPN member pharmacy relative to out-of-network pharmacies. In some PPNs, medications obtained from out-of-network pharmacies are not reimbursed. Thus, PPN member pharmacies charge lower fees and offer patient supports in return for higher sales volumes.

PPNs come in different varieties. Some are “closed,” meaning only selected pharmacies participate; others are “open,” where any pharmacy that can offer services at a specific price can join the network.22 Some industry analysts reserve the descriptor “closed” to refer to PPNs in which plan members who obtain their medication at a pharmacy in the network will be covered for the drug but not at a pharmacy outside the network. These analysts define “open” PPNs as those in which drugs obtained at an out-of-network pharmacy are covered, albeit with higher copays. Some insurers offer exemptions so that beneficiaries can obtain services from any pharmacy without any additional copays.33 Hannay, Chris, Clare O’Hara, and Susan Krashinsky Robertson. 2025b. “Ontario Considers Rule to Limit Exclusivity Deals Between Insurers and Pharmacies.” The Globe and Mail. May 30. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/economy/article-ontario-considers-rule-limit-exclusivity-deals-insurers-and-pharmacies/. They can apply to all medications, medications used to manage chronic conditions, or just to high-cost “specialty” medications.

There are no publicly available statistics on the use of PPNs or what kinds of medications are provided via PPNs. Bonnett reports, however, that PPNs typically distribute specialty medications.44 Bonnett, Chris. 2025. “Preferred Pharmacy Networks – Innovation or Inertia?” Healthy Debate. March 19. https://healthydebate.ca/2025/03/topic/preferred-pharmacy-networks-innovation-inertia/. These are injectable biologics and conventional drugs that cost over $10,000 per person annually. Specialty medications are used by less than two percent of private drug plan claimants in Canada, but they accounted for about 28 percent of total private drug plan spending in 2023.55 Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2024. Submission to the Ontario Ministry of Finance: Consultation on the Preferred Provider Networks in the Employer-Sponsored Drug Insurance Sector. October 22. https://www.clhia.ca/web/CLHIA_LP4W_LND_Webstation.nsf/page/8517732B6CF0E30985258BBE0080951B/$file/ON%20Ministry%20of%20Finance%20-%20PPNs%20in%20Employer-Sponsored%20Drug%20Insurance%20Sector.pdf; Express Scripts Canada. 2024. 2024 Express Scripts Canada Drug Trend Report. https://www.express-scripts.ca/sites/default/files/2024-05/2024_ESC_DTR_EN.pdf. They are typically used to manage complex, chronic conditions, like multiple sclerosis, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis. The most expensive specialty drugs cost over $1 million a year.66 Canadian Drug Insurance Pooling Corporation. 2025. “Pooling Results.” https://cdipc-scmam.ca/cdipc-information/. PPN member pharmacies provide discounts on the usual and customary fees that pharmacies charge to provide specialty medications; these fees can run into the thousands of dollars.77 Milne, Vanessa, Mike Tierney, and Irfan Dhalla. 2016. “Should Markups on High-Cost Drugs Be Capped?” Healthy Debate. December 2. https://healthydebate.ca/2016/12/topic/markup/.

Pharmacy stakeholders across Canada have, in recent years, petitioned governments to ban or at least regulate PPNs. These advocacy efforts have so far been successful. The Ontario government is considering regulating PPNs.88 Hannay, Chris, Clare O’Hara, and Susan Krashinsky Robertson. 2025. “Ontario Considers Rule to Limit Exclusivity Deals Between Insurers and Pharmacies.” The Globe and Mail. May 30. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/economy/article-ontario-considers-rule-limit-exclusivity-deals-insurers-and-pharmacies/. The Ontario College of Pharmacists (OCP) – Ontario’s pharmacy regulator – is exploring ways of sanctioning pharmacists and pharmacies that participate in closed PPNs.99 Ontario College of Pharmacists. 2024. “OCP Board Adopts Position on Closed Preferred Provider Networks.” July 8. https://www.ocpinfo.com/ocp-board-adopts-position-on-closed-preferred-provider-networks/. It argues that closed specialty drug PPNs cause patients to obtain care from multiple pharmacies – specialty drugs from a PPN and other drugs from another pharmacy – and this fragmentation of patient care is harmful. The federal Competition Bureau has previously advocated for PPNs, suggesting that these will improve pharmacy services price competition.1010 Competition Bureau. 2008. Benefiting from Generic Drug Competition in Canada: The Way Forward. Ottawa: Industry Canada. November. https://competition-bureau.canada.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/2022/GenDrugStudy-Report-081125-fin-e.pdf. The Bureau, however, has recently expressed concerns about closed PPNs. It worries that if closed PPNs become more commonplace, then “… this situation may raise barriers to competition that could impact the ability of small and independent pharmacies to enter the market, expand, and serve their communities. If pharmacy markets become more concentrated and less contestable as a result, then Canadians could be deprived of the benefits of competition in a crucial area of healthcare.”1111 Competition Bureau. 2024. “Competition Bureau Submission to the Ontario Ministry of Finance Consultation on the Preferred Provider Networks in the Employer-Sponsored Drug Insurance Sector.” October 22. https://competition-bureau.canada.ca/how-we-foster-competition/education-and-outreach/competition-bureau-submission-ontario-ministry-finance-consultation-preferred-provider-networks.

Following a complaint by the Canadian Pharmacists Association,1212 Canadian Pharmacists Association. 2024. “CPhA Files Abuse of Dominance Complaint with Competition Bureau Against ESC’s New Service Fee.” February 28. https://www.pharmacists.ca/news-events/news/cpha-files-abuse-of-dominance-complaint-with-competition-bureau-against-esc-s-new-service-fee/. the Competition Bureau also launched an investigation into Express Scripts Canada, a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). Among other functions, Express Scripts Canada manages a network of preferred specialty pharmacies for various insurance carriers and operates its own mail-order pharmacy. The Competition Bureau is investigating, among other things, whether Express Scripts Canada’s specialty pharmacy agreements have harmed competition.1313 Competition Bureau. 2025. “Competition Bureau Advances an Investigation into Express Scripts Canada’s Business Practices in the Pharmacy Sector.” https://www.canada.ca/en/competition-bureau/news/2025/03/competition-bureau-advances-an-investigation-into-express-scripts-canadas-business-practices-in-the-pharmacy-sector.html.

In this Commentary, I review the possible public policy concerns with PPNs. Pharmacy stakeholders advocate for stricter government regulation of PPNs, and the firms that administer them – insurers and PBMs.1414 Canadian Pharmacists Association. “Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Fact Sheet.” https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/PBM_FactSheet_final.pdf. They argue that without this regulation, Canada’s prescription drug benefits system will move further towards the system in the US, where PPNs are commonly used.1515 Neighbourhood Pharmacy Association of Canada. 2025. Consultation on Preferred Provider Networks in Drug Group Insurance Plans (https://neighbourhoodpharmacies.ca/sites/default/files/2025-07/Submission%20to%20ON%20MoF%20Re%20PPN%20Policy%20Options%202025%2007%2028%20F.pdf). The US drug benefits system is widely regarded as being dysfunctional. I compare the drug benefits systems in the United States and Canada and assess the merit of these claims. The Competition Bureau is concerned that the use of PPNs will increase the market shares held by a few corporate pharmacy chains at the expense of small and independent pharmacies (SIPs). I agree that avoiding industry concentration is a legitimate policy goal. I thus consider the financial impact that existing specialty drug PPNs have had on SIPs and consider the prospects that closed PPNs in Canada will expand to include not just specialty drugs but all prescription drugs. Finally, some pharmacy stakeholders have expressed concerns that closed PPNs present grave risks to patient health. I address these claims.

Briefly, I find that Canada’s drug benefits system is structurally different from the system in the US. The well-publicized problems in the US are unlikely to occur in Canada. There are no publicly available data to determine whether PPNs have caused growing corporate concentration in Canada’s community pharmacy sector. I do find, however, that even if specialty medication PPNs were banned, most small and independent pharmacies would not see a large proportional increase in revenues. Based on my review of the employer-sponsored drug benefits system, I doubt that PPNs will expand beyond the provision of specialty medications. There are limited data on the adverse patient health impacts of PPNs. However, problems with fragmentation can be mitigated with more robust sharing of patient clinical information between PPN pharmacies and out-of-network pharmacies.

A Comparison of the Canadian and US Drug Benefits Systems

The Canadian Drug Benefits System

Canada, like the US, has mixed public-private drug coverage. About two-thirds of Canadians have private drug coverage. Typically, this coverage is part of a suite of health benefits – such as dental and vision care – that public sector and larger private sector employers provide to full-time, permanent employees and their dependents.1616 Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2023. Canadian Life & Health Insurance Facts: 2023 Edition. Toronto: Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. http://clhia.uberflip.com/i/1508207-canadian-life-and-health-insurance-facts-2023-edition/0; Conference Board of Canada. 2022. “Understanding the Gap 2.0: A Pan-Canadian Analysis of Prescription Drug Insurance Coverage.” Data Briefing. Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada. May 6. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/in-fact/understanding-the-gap/. Prescription drug coverage is the single largest component, accounting for $15.3 billion (42 percent) of the $36.6 billion spent on health benefits in 2023.1717 Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2024. Canadian Life & Health Insurance Facts: 2024 Edition. Toronto: Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. https://www.clhia.ca/facts. In addition to employers, student associations, unions, and professional associations also arrange health benefits for their members.1818 There is also individual coverage available, but the individual market is small, accounting for only 9 percent of private health insurance premiums in 2023 (ibid). As in the US, public drug coverage in Canada is mainly extended to those outside of the labour market, such as seniors and those receiving social assistance payments. Provincial governments, however, also provide “universal” drug coverage with income-contingent deductibles to all residents who incur high drug costs relative to income.1919 Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2024. Public Drug Plan Designs, 2021/22. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information. January 30. https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/npduis/analytical-studies/supporting-information/public-drug-plan-designs.html. I estimate that about 45 percent of drug costs in Canada, measured using the dollar value of the drug claims paid (including beneficiary copays), are paid by private drug plans.2020 Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2024. “National Health Expenditure Trends, 2024: Table G.14.1 – Expenditure on Drugs by Type and Source of Finance in Millions of Current Dollars, Canada, 1985 to 2024.” Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-health-expenditure-trends.

The employer or other group plan sponsor, often with the aid of a benefits advisor, will obtain health benefits coverage from an insurance carrier. This coverage can either be insured or administrative services only (ASO). With insured coverage, the sponsor pays premiums, and the insurer absorbs the financial risk. The plan sponsor can choose some plan features, such as benefit maximums, but has limited ability to customize the plan. Instead, the carrier controls much of the coverage design, including the use of PPNs. With an ASO plan, the sponsor pays the prescription drug costs incurred by plan beneficiaries plus a processing fee that is typically a percentage of the drug cost. The sponsor thus absorbs the financial risk; some ASO plans do have a “stop loss” option that limits the sponsor’s financial exposure.2121 Maximum Benefit. 2019. “Administrative Services Only (ASO).” Winnipeg: Maximum Benefit. https://www.maximumbenefit.ca/uploads/document/mb_quoteaso4panelonline_0319_e.t1561583166.pdf. The ASO plan sponsor controls the health benefit design, including the use of PPNs.

The health benefit ASO plans are often used by large employers, particularly those in the public sector. For example, the federal government’s Public Service Health Care Plan, which covers over 1.7 million plan members and their dependents, is an ASO plan administered by Canada Life (McCauley 2024). About 30 percent of private plan beneficiaries are public sector employees whose benefits are sponsored by government employers (Health Canada 2019).

The primary reason that larger employers prefer ASO plans is that they are less expensive than insured plans. One benefits advisor reports that for a 3-to-10-employee firm, 25-32 percent of premiums paid for insured plans would cover underwriting and administration costs and profit, and the remainder would be the cost of claims. For an 11-50 employee firm, 20-25 percent of premiums cover these costs and profit.2222 HMA Benefits. 2025. “What Is a Target Loss Ratio?” Whitby: HMA Benefits. https://www.hmabenefits.ca/blog/target-loss-ratio. Costs would be lower in ASO plans as the employer bears the financial risk, and any fixed plan costs are amortized over a larger volume of beneficiaries.

How common is ASO coverage? A recent study reported on the ASO share of private drug plan expenditure (Patented Medicine Prices Review Board 2025). This study analyzed a large sample of Canadian private drug plans, covering 167 million prescriptions and $13.5 billion in total prescription costs in 2023. The study found that plans with more than 1,000 claimants accounted for just 8 percent of all plans but were responsible for 90 percent of total claimants, 89 percent of total drug costs, and 89 percent of specialty drug costs. These large plans would almost invariably be ASO plans. Conversely, small plans (fewer than 50 claimants) comprised 68 percent of plans but accounted for just 2 percent of total claimants and 2 percent of total drug costs. It appears that many of these smaller insured plans limit coverage of specialty drugs because they must absorb the cost of annually recurring high-cost claims. This occurs when a plan beneficiary uses a specialty drug to treat an ongoing chronic condition. Because insurance contracts are renegotiated annually, the cost of these high-cost claims eventually becomes incorporated into the insurance premium. To avoid premium escalation, many smaller employers evidently either do not cover specialty drugs or impose annual benefit maximums.2323 Henricks, Paul, Courtney Abunassar, and Laura Roulston. 2024. Issues and Opportunities to Modernize Private Drug Plan Sustainability in an Evolving Market. Ottawa: PDCI Market Access. August. https://innovativemedicines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/PDCI_Private_Market_Sustainability_2024.pdf; West, David. 2016. Individual Submission to the Standing Committee on Health Regarding a National Pharmacare Program. September 20. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Brief/BR8530529/br-external/WestDavid-e.pdf. Beneficiaries of these plans would typically be referred to their provincial universal drug plan for specialty medication coverage.

The final actor in the cast of characters in the drug benefit sector – pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) – provide several services to insurers. PBMs design drug plan formularies – the set of drugs that are covered by the plan and the restrictions (if any) on their reimbursement. PBMs also process prescription drug claims that community pharmacies submit electronically for reimbursement. The PBM ensures that drug claims are eligible for reimbursement, determines patient copays, and then reimburses pharmacies.2424 Express Scripts Canada. 2023. Value of Pharmacy Benefit Management Services to Pharmacies in Canada. Mississauga: Express Scripts Canada. https://www.express-scripts.ca/sites/default/files/2023-11/PBMValueServicesReportEN.pdf.

The US Drug Benefits System

The US drug benefit sector also includes insurers, PBMs, and pharmacies. There is, however, much more industry concentration and vertical integration. In the US, three vertically integrated conglomerates – CVS Health, Cigna, and UnitedHealth Group – dominate the drug benefits market. Each of these firms combines, among other entities, a drug insurer, a PBM, a mail-order pharmacy and, in the case of CVS Health, a bricks-and-mortar pharmacy chain.2525 Fein, Adam J. 2025. “Mapping the Vertical Integration of Insurers, PBMs, Specialty Pharmacies, and Providers: DCI’s 2025 Update and Competitive Outlook.” Drug Channels. April 9. https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/04/mapping-vertical-integration-of.html. The three PBMs, the CVS Caremark business of CVS Health, the Express Scripts business of Cigna, and the Optum Rx business of UnitedHealth Group, manage about 80 percent of US prescription claims.2626 Fein, Adam J. 2025. “The Top Pharmacy Benefit Managers of 2024: Market Share and Key Industry Developments.” Drug Channels. March 31. https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/03/the-top-pharmacy-benefit-managers-of.html. Each PBM processes claims for the insurer that belongs to the conglomerate, plus external insurers and self-insured drug plans as well. Each PBM uses the large number of drug plan beneficiaries whose claims it manages to extract price discounts from drug manufacturers and from pharmacies that are not owned by the PBM’s conglomerate. If a pharmacy does not provide price concessions, then the PBM will increase the copay amounts that drug plan beneficiaries must pay out of pocket to use the pharmacy, or simply not reimburse beneficiaries who use the pharmacy’s services.2727 Federal Trade Commission. 2024. Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Powerful Middlemen Inflating Drug Costs and Squeezing Main Street Pharmacies. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission. July. https://rupri.public-health.uiowa.edu/publications/policybriefs/. PBMs use the same strategy when negotiating discounts on the prices of branded drugs that compete within the same therapeutic class. For example, Zepbound, Wegovy, and several other branded GLP-1 receptor agonists are used to manage type 2 diabetes and body weight. The PBM CVS Caremark assigns the lowest copay to Wegovy and no longer covers Zepbound; presumably, Wegovy’s manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, offered the largest discounts to the PBM.2828 Robbins, Rebecca, and Reed Abelson. 2025. “Why Patients Are Being Forced to Switch to a 2nd-Choice Obesity Drug.” The New York Times. May 11. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/11/health/zepbound-wegovy-weight-loss-drugs.html.

These arrangements have led to undesirable outcomes. First, branded drug manufacturers have rapidly raised list prices in an attempt to preserve their margins. In 2008, US patented drug list prices were about 1.5 times higher than Canadian patented drug list prices. By 2021, US list prices were over 3.5 times Canadian prices (Grootendorst 2024). There is evidence that PBMs have extracted most of these price increases in the form of confidential rebates (off-invoice price discounts) (Dickson et al. 2023). Indeed, branded drug manufacturer rebates paid to US PBMs reached an estimated $334 billion in 2023 (Martin 2025). PBMs claim that they pass most of these savings back to insurers, but given the lack of transparency, including the use of accounting manoeuvres to hide rebates, it is difficult to verify how much money PBMs retain.2929 Tozzi, John. 2023. “Drug Benefit Firms Devise New Fees That Go to Them, Not Clients.” Bloomberg Businessweek. August 22. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-08-22/drug-price-negotiations-enrich-pharmacy-benefit-managers; Federal Trade Commission. 2024. Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Powerful Middlemen Inflating Drug Costs and Squeezing Main Street Pharmacies. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission. July. https://rupri.public-health.uiowa.edu/publications/policybriefs/. Because of the vagaries of the PBM contracts, pharmacies have increased their list prices for prescription drugs.3030 Evans, Alex, and Charlene Rhinehart. 2023. “How Does Drug Pricing Work in the U.S.?” GoodRx Health. September 19. https://www.goodrx.com/hcp-articles/providers/how-does-drug-pricing-work-in-the-us. The high drug manufacturer and pharmacy list prices create further demand by drug plan sponsors for the three large PBMs to negotiate price discounts. This dynamic further cements the big three PBMs’ market dominance. The high list prices also create access issues for those without insurance.

Second, PBMs have squeezed pharmacy margins, and these reduced margins are cited as a primary reason for the closure of independent pharmacies in the United States (Guadamuz et al. 2024).3131 Abelson, Reed, and Rebecca Robbins. 2024. “The Powerful Companies Driving Local Drugstores Out of Business.” The New York Times. October 19. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/19/business/drugstores-closing-pbm-pharmacy.html. Finally, recall that PBMs set beneficiary copays for drugs inversely proportional to the size of the secret discount that the drug manufacturer gives the PBM. As a result, manufacturers of lower-cost alternatives – such as generic versions of branded drugs or biosimilar versions of originator biologics – are unable to pay the largest rebates. Thus, beneficiary copays may be particularly high for these less costly products. Startups like the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company bypass insurers and PBMs and sell generics and some branded drugs directly to consumers for less than the insurance copays.3232 Cuban, Mark. 2024. “Five Ways That Big PBMs Hurt U.S. Healthcare—and How We Can Fix It.” Drug Channels. March 21. https://www.drugchannels.net/2024/03/mark-cuban-five-ways-that-big-pbms-hurt.html.

Differences Between the Canadian and US Drug Benefits Systems

Is Canada moving towards a US-style system, as pharmacy stakeholders suggest? If it is, it has a long way to go to reach the dysfunction of the US system. The reason is that Canada’s drug benefits system differs from the US system in several important ways. First, over half of drug coverage in Canada, measured using the dollar value of the drug claims paid (including copays), is publicly administered by federal, provincial, and territorial government drug plans.3333 Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2023. Prescribed Drug Spending in Canada, 2023. Ottawa, ON: CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/en/prescribed-drug-spending-in-canada-2023. Some governments contract out claims processing to a PBM, but governments administer the drug plans themselves. To my knowledge, public drug plans in Canada do not use PPNs. These are used exclusively by private plans outside of Quebec, whose government has banned their use. In the United States, in contrast, the large public drug plans, Medicare Part D for seniors and the healthcare plans that qualify for Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) subsidies are administered by competing private insurers that offer coverage that meet eligibility conditions. Thus, the privately insured share of prescription drug spending, which is the component of spending that PPNs can influence, is much higher in the US than it is in Canada.

The second structural difference between the US and Canadian systems is that there is much less vertical integration amongst actors in Canada’s drug benefit system. Recall that the US drug benefit system is dominated by three large consortia, each of which provides insurance, PBM, and pharmacy services. The PBMs owned by the big three control about 80 percent of prescriptions. The pharmacies owned by the big three have a 43 percent share of 2024 prescription revenues.3434 Fein, Adam J. 2025. “The Top 15 U.S. Pharmacies of 2024: Market Shares and Revenues at the Biggest Chains, PBMs, and Specialty Pharmacies.” Drug Channels Institute. March 11. https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/03/the-top-15-us-pharmacies-of-2024-market.html. Each of these consortia reportedly pays lower reimbursement to external pharmacies than to the pharmacies they own, thus reinforcing their dominance.

The situation in Canada is different. The two large Canadian PBMs, Express Scripts Canada and Telus Health, which process 80 percent of private plan claims nationally,3535 Canadian Pharmacists Association. “Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Fact Sheet.” https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/PBM_FactSheet_final.pdf. are not owned by the major insurers.3636 Canadian Drug Insurance Pooling Corporation. “Corporate Information.” https://cdipc-scmam.ca/cdipc-corporate-information-menu/. The remaining 20 percent of claims are processed by smaller PBMs that are owned by insurers. These include Canada Life’s ClaimSecure, GreenShield Canada’s HBM+, and Blue Cross Canada’s PBM.3737 Canadian Pharmacists Association. “Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Fact Sheet.” https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/PBM_FactSheet_final.pdf. These smaller PBMs, despite being owned by insurers, are unlikely to have significant market power. The three largest insurers – Sun Life, Canada Life, and Manulife – collectively manage about 58 percent of all privately insured lives.3838 Henricks, Paul, Courtney Abunassar, and Laura Roulston. 2024. Issues and Opportunities to Modernize Private Drug Plan Sustainability in an Evolving Market. Ottawa: PDCI Market Access. August. https://innovativemedicines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/PDCI_Private_Market_Sustainability_2024.pdf. Sun Life, Manulife, and the smaller health benefit providers rely on external PBMs.

The overwhelming majority of community (retail) pharmacies are also independent from PBMs and insurers. The insurer GreenShield and the PBMs Express Scripts Canada and Telus Health do operate mail-order pharmacies in several provinces. Sun Life has a minority ownership stake in the mail-order pharmacy Pillway. In Ontario, at least, these mail-order pharmacies are small. Pillway employs five pharmacists, GreenShield’s pharmacy employs eight, Express Scripts Canada’s pharmacy employs 14, and Telus’ pharmacy employs seven.3939 Ontario College of Pharmacists. “Find a Pharmacy.” https://members.ocpinfo.com/tcpr/public/pr/en/#/forms/new/?table=0x800000000000003C&form=0x800000000000002B&command=0x80000000000007C4. These 34 pharmacists constitute a small percentage of the 12,995 pharmacists who work in Ontario’s 5,019 outpatient pharmacies.4040 National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities. 2025. “National Statistics – January 1, 2025.” Ottawa: NAPRA. https://www.napra.ca/national-statistics. Thus, there is limited opportunity for Canadian insurers to direct business to in-house pharmacies or pay lower reimbursement to external pharmacies, as is common in the US.

The third structural difference between the US and Canadian drug benefit systems is that in the US, insurers and drug plan sponsors rely on PBMs to negotiate discounts off inflated drug manufacturer and pharmacy list prices. Manufacturers and pharmacies inflate list prices to preserve their margins when negotiating with PBMs. (Thus, PBMs have been described as both the “arsonist and firefighter”). This dynamic does not occur in Canada. For one, the federal regulator, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB), caps introductory list prices of new patented drugs using the prices charged for similar drugs within Canada or internationally. Manufacturers are unable to raise list prices post-launch by more than the rate of inflation. There is also no evidence that pharmacies have defensively raised their listed fees. Thus, there is less demand by Canadian drug plan sponsors for PBMs to negotiate discounts off list prices. Certainly, private insurers negotiate confidential rebates off patented drug list prices, but these rebates are said to be modest.4141 Gagnon, Marc-André, and Quinn Grundy. 2024. Preferred Provider Networks in Employer-Sponsored Drug Insurance Sector: Some Necessary Considerations. Submission to the Ontario Ministry of Finance. October 21. https://carleton.ca/ghostmanagement/wp-content/uploads/Brief-PPN-Ontario_QG-FInal.pdf.

Pharmacy Reimbursement Controls in the Canadian Drug Benefits System

There is limited detailed information on how private drug insurers regulate pharmacy fees. These fees consist of a percentage markup on drug cost and a dispensing fee, typically unrelated to drug cost. Historically, drug insurers reimbursed pharmacies’ usual and customary fees, passing on this cost to drug plan sponsors. Industry analysts suggest that the lack of cost control is related to the use of ASO plans. Providers administering ASO plans are paid a percentage of claims volumes, so that there are no direct incentives to control costs. This is corroborated by a 2015 study that interviewed stakeholders in the group health plan sector. The study authors interviewed a benefits consultant who indicated that “there has been a fair bit of inertia, you know, amongst the providers out there in actually doing something too radical, too leading edge” because “there’s no direct financial incentive for insurance companies or pharmacy benefit managers to actually help employers save money” (O’Brady et al. 2015).

Insurers gradually introduced pharmacy fee controls. Some plan sponsors capped dispensing fee reimbursement to encourage drug plan beneficiaries to shop around. (This is the case for the drug benefits that the University of Toronto offers its faculty). Some insurers began to monitor pharmacies’ usual and customary fees and then capped the fees at some percentile of the distribution of these fees (Gagnon-Arpin et al. 2018). Manulife reports that it imposes lower caps on the allowed markups on high-cost drugs.4242 Manulife. 2025. “The Cost of Picking Up Your Prescription.” Toronto: The Manufacturers Life Insurance Company. July. https://www.content.uat.websinc.ca/1090/English/PlanDetails/PlanD/Understanding%20RC%20Limits%20Pharm%20(web%20version)%20-%20GC2148E.pdf. Canada Life reports that it caps reimbursed markups and fees on drugs dispensed to members of the federal Public Service Health Care Plan.4343 Public Service Health Care Plan Administration Authority. 2025. “Drug Benefit.” Ottawa: PSHCP-AA. https://pshcp.ca/benefits/extended-health-provision/drug-benefit/. These practices, however, are not universally applied. An industry source told me that some smaller insurers negotiate markups with the pharmacy chains. They do not unilaterally set pharmacy fees at low levels out of concern that pharmacies will not accept clients from the drug plans that they manage.

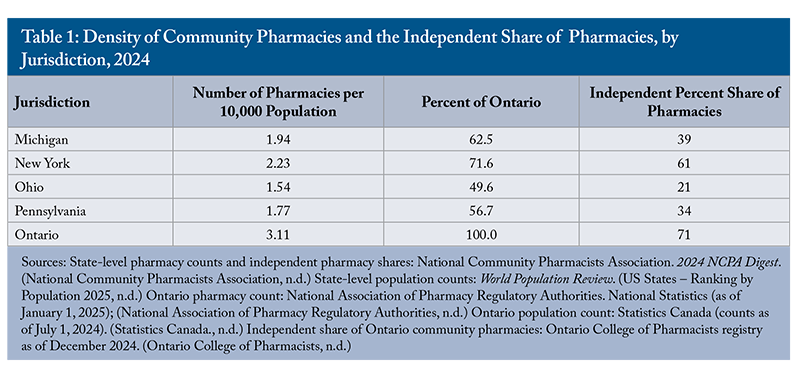

Even with the use of closed specialty drug PPNs, private drug plan reimbursement of pharmacy fees appears more generous than public plan reimbursement of these fees, especially in Quebec (Chamoun et al. 2022).4444 Grammond, Stéphanie. 2023. “Pharmacie: Des honoraires de 100 000 $… pour un seul patient.” La Presse. April 1. https://www.lapresse.ca/debats/editoriaux/2023-04-01/pharmacie/des-honoraires-de-100-000-pour-un-seul-patient.php. This may explain why the Canadian Pharmacists Association and other pharmacy stakeholders have opposed a national pharmacare program, as this would extend public plan reimbursement rates to all prescriptions. Private drug plan reimbursement of pharmacy fees in Canada also appears to be markedly more generous than pharmacy fee remuneration in the US. As noted earlier, Canadian insurers do not routinely use PBMs to extract fee concessions from community pharmacies in exchange for higher patient volumes or provide lower fees to pharmacies that they do not own. The US-Canada difference in the generosity of pharmacy reimbursement is evident by comparing the number of community pharmacies per capita in Ontario with those in the US states that are near Ontario (Table 1). Pharmacies typically derive at least half of their sales revenue from dispensing, so the generosity of dispensing remuneration will directly affect the density of pharmacies.

As Table 1 indicates, the pharmacy density in states surrounding Ontario ranges from 50 to 70 percent of Ontario’s density. In Ontario, over 70 percent of community pharmacies are independently owned and less than 30 percent are corporately owned. The share of pharmacies that are independent in the four US states is markedly lower. Independent pharmacies represent about 35 percent of all US community pharmacies.4545 National Community Pharmacists Association. 2024. NCPA Digest. Columbus, OH: NCPA. October 27. https://pharmacybookshelf.cardinalhealth.com/view/491779965/2/. Thus, even with its use of closed specialty drug PPNs, the Canadian drug benefits system evidently more generously reimburses pharmacies than does the US system.4646 Canada also has a relatively high density of pharmacies compared to its international peers. There are three pharmacies per 10,000 population in Canada and two pharmacies per 10,000 population in the US. By comparison, the density of pharmacies per 10,000 in two commonwealth countries, Australia and the UK, is 2.3 and 2.1, respectively. See: OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/7a7afb35-en.

Impact of Closed Specialty Drug PPNs on Small and Independent Pharmacies in Canada

In Canada, community pharmacies are distinguished by their ownership type: non-corporate pharmacist-owned and corporate. The former group consists mainly of what the Competition Bureau calls small and independent pharmacies (SIPs). The latter group consists of chain pharmacies, most of which are owned by the supermarket operators Loblaw, Empire, and Metro, as well as the big-box retailers Walmart and Costco. The corporate owner hires a pharmacist to operate the pharmacy on its behalf. These stores tend to operate at a larger scale than do SIPs.

I share the Competition Bureau’s view that a highly concentrated community pharmacy market, where a few corporate chains accrue most sales and SIPs have very small shares, is undesirable. It appears that at present, however, the community pharmacy sector, at least in Ontario, is not overly concentrated. As noted in Table 1, about 70 percent of pharmacies in Ontario are SIPs. They fill closer to 50 percent of prescription volumes because they tend to operate at a relatively small scale (Pukhov et al. 2025). It is possible, however, that the community pharmacy sector is becoming more concentrated over time because of the growth in specialty medication use. Unfortunately, there are no publicly available data to determine if this is the case.

This issue can, however, be examined indirectly. Specialty medication PPNs will make the pharmacy sector more concentrated to the extent that: (1) a greater share of privately paid specialty medications is distributed through PPN pharmacies, and (2) specialty medications account for a larger portion of privately paid pharmacy net revenues. Although no public data are available on the first point, some evidence exists for the second. In Appendix 1, I estimate the net revenue that community pharmacies collectively earn from dispensing privately insured specialty medications. I focus on the provinces outside Quebec because that province has banned PPNs. I estimate that the privately paid specialty medication share of core pharmacy net revenues (dispensing fees, markups, and remuneration for providing vaccinations and other health services) in 2023 was about 5 percent. If all specialty drugs were dispensed via a corporate PPN, SIPs would forfeit these revenues. However, given that it is not a major revenue source, the loss of these revenues would not appear to tip the balance between economic profits and losses for most pharmacies.

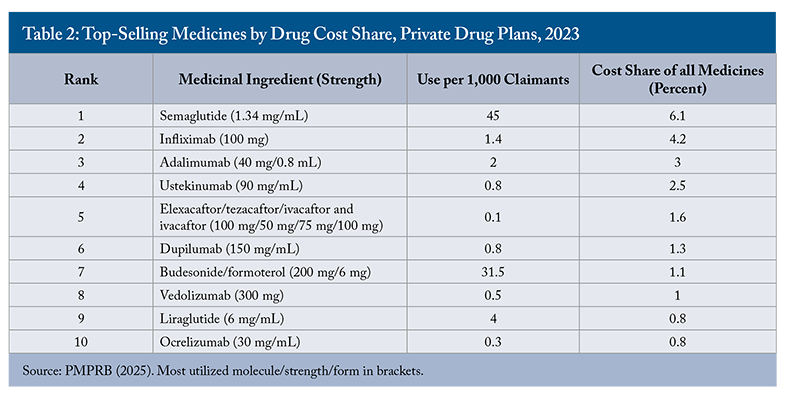

A recent study examined the medications that account for the largest private drug plan expenditure in 2023 (PMPRB 2025). Table 2 lists the top ten products, six of which are “mab” biologic medications (e.g., Infliximab, Adalimumab) used to treat cancer and autoimmune conditions. Pharmacies that wish to administer these medications would need to train staff and possibly invest in special equipment, as some are administered via intravenous infusion. It seems improbable that every community pharmacy would incur the costs needed to administer these medications, given that over 98 percent of plan beneficiaries do not use them. Thus, even with a PPN ban, it seems that many pharmacies would refer patients to a specialty pharmacy to obtain at least some specialty medications. PPN bans will thus not automatically level the playing field.

Thus, it appears that most SIPs would not accrue significant revenues from providing specialty drugs to private drug plan beneficiaries. As further evidence, the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA) notes that the specialty pharmacy chains have a large share of the specialty market in Quebec, even though PPNs are illegal there.4747 Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2024. Submission to the Ontario Ministry of Finance: Consultation on the Preferred Provider Networks in the Employer-Sponsored Drug Insurance Sector. October 22. https://www.clhia.ca/web/CLHIA_LP4W_LND_Webstation.nsf/page/8517732B6CF0E30985258BBE0080951B/$file/ON%20Ministry%20of%20Finance%20-%20PPNs%20in%20Employer-Sponsored%20Drug%20Insurance%20Sector.pdf. Thus, it appears that even if PPNs were banned in the rest of Canada, specialty pharmacy chains would have sizeable market shares. This seems plausible given their expertise in handling inventories of these temperature-sensitive medications, their large scale, and their partnership with manufacturer-sponsored patient support programs.

The takeaway from this analysis is that, given current rates of expenditure on specialty drugs, it seems unlikely that the financial viability of most SIPs hinges on privately insured specialty drug sales. This suggests that the community pharmacy market is not becoming more concentrated. This could change, given that the specialty medication share of private plan drug spending appears to be increasing over time. Thus, it is important to monitor trends in pharmacy sector concentration.

Assessing the Likelihood of PPN Expansion in Canada

While some drug plans use closed PPNs to distribute all medications,4848 Benchetrit, Jenna, and Nisha Patel. 2024. “Telus Health Only Reimbursing Employee Drug Prescriptions Filled through Its Virtual Pharmacy.” CBC News. March 19. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/telus-health-employees-must-use-companys-virtual-pharmacy-1.7134413. as noted earlier, most closed PPNs in Canada distribute specialty medications only. The Competition Bureau is concerned that closed PPNs will expand to include refill prescriptions for maintenance drugs or all prescribed drugs. How likely is this?

To address this question, it is helpful to understand how the generosity of private drug benefits is determined. Most private coverage is provided as an employment-related benefit. The cost of these health benefits – along with salaries, wages, pension contributions, and payroll taxes – constitutes the employer’s personnel cost. Employers determine the total compensation they are willing to offer to attract and retain employees, balancing salary and health benefits to suit the preferences of their workforce. They may provide very generous, unrestricted health benefit coverage, albeit with lower salary compensation, or restrictive health benefit coverage and higher salaries, or something in between. The employer, in effect, assesses employee willingness to trade off salary for health benefits. Larger employers might also directly bargain with an employee union or association over the generosity of health benefits and monetary compensation.

It seems unlikely that public sector or unionized employees, who are accustomed to a generous drug benefit, would be willing to accept expansions of the types of drugs that are only available through PPNs (O’Brady et al. 2015). Indeed, some recent employer attempts to introduce closed PPNs for all drugs have been opposed by employee associations.4949 Ward, Lori. 2017. “‘A Broken System’: Why Workers Are Fighting Mandatory Mail-Order Drug Plans.” CBC News. August 16. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/drugs-pharmacies-ppns-1.4250185.

The expansion of closed PPNs also seems unlikely in non-union private sector industries that pay well. Economics predicts that employee demand for health benefits – the amount of salary they are willing to exchange for health benefits – is higher the more that the employee is paid. The reason is that supplemental health insurance is a “normal” good, meaning that demand for it increases with income (Costa and García 2003). Moreover, the price an employee must pay for health benefits is lower the more that the employee is paid. The reason is that employee health benefits are subject to neither federal nor provincial personal income tax. (Quebec is the exception as it taxes employee health benefits).5050 Revenu Québec. 2025. “Medical Expenses – Taxable Benefits.” Revenu Québec. https://www.revenuquebec.ca/en/businesses/source-deductions-and-employer-contributions/special-cases-source-deductions-and-employer-contributions-in-certain-situations/taxable-benefits/list-of-taxable-benefits/other-benefits/medical-expenses-taxable-benefits/. As a result, the after-tax income that an employee forgoes to obtain a dollar of health benefit – the employee’s cost of coverage – is lower the higher the employee’s marginal tax rate. Marginal tax rates, in turn, increase with income. For instance, a highly paid employee paying a 54 percent marginal tax rate gives up only $0.46 after-tax income for $1 of health coverage. An employee with lower earnings paying a 23 percent marginal tax rate gives up $0.77 for $1 of health coverage. Thus, one would expect drug benefits to be more generous and unrestricted in higher-paying occupations and industries because the price employees in these sectors pay for coverage is relatively low, while their willingness to pay for it is relatively high. This is corroborated by evidence that private drug insurance is more comprehensive the higher the employment income (Barnes and Anderson 2015; Health Canada 2019). This suggests that PPN use will not expand beyond specialty drugs in public sector drug plans and higher-paying or unionized private sector plans, if they are used at all.

PPNs that apply to all, or most drugs, could see more adoption in smaller, insured plans that cover private sector employees with more modest earnings. However, as noted, insured plans account for about 10 percent of private drug spending. Thus, even if such plans were to adopt closed PPNs, the impact on small independent pharmacy revenues would be modest.

Another reason why it is unlikely that PPNs will expand beyond specialty drugs is that the savings are smaller. Specialty drug PPNs achieve their savings by discounting the 12-15 percent markups that pharmacies customarily charge (Gagnon-Arpin et al. 2018). A 13 percent markup on a biologic that costs $200,000 is $26,000. Employers and other ASO plan sponsors are evidently willing to sign exclusive deals to lower these fees. Over 75 percent of prescriptions, however, are filled with generic drugs. In 2024, the average cost of a prescription filled with a generic drug, including markups and dispensing fees, was $22.53.5151 Canadian Generic Pharmaceutical Association. 2025. “Resources.” https://canadiangenerics.ca/resources/. The average dispensing fee was likely around $11.5252 MoneyGuide.ca. 2025. “Drug Dispensing Fees.” https://moneyguide.ca/fees/drug-dispensing-fees/. Even if the markup is 15 percent, the markup component of the prescription cost is only $1.50. Thus, the opportunity for markup savings is limited for most prescriptions dispensed. There may be some dispensing fee savings available from online pharmacies, but cost-conscious drug plan sponsors can obtain these savings simply by reducing the dispensing fee reimbursement cap to the amount charged by the online pharmacy. If they do, there is no need to create a closed PPN.

For all these reasons, it appears that closed PPNs will not expand to include non-specialty medications.

Impact of Closed PPNs on Patient Health

There is conflicting evidence on the impact of closed specialty drug PPNs on patient health. Pharmacy stakeholders argue that closed PPNs adversely affect patients owing to the fragmentation of care. Fragmentation occurs when a patient obtains care from different healthcare providers. Problems ensue when pertinent clinical information is not shared between providers. Thus, PPNs can create problems if a drug plan beneficiary obtains some medications from a PPN member pharmacy and other medications from a different pharmacy, perhaps the beneficiary’s regular pharmacy. The problem occurs when the PPN member pharmacy and the regular pharmacy do not share information relevant to the patient’s care. Some pharmacy stakeholders suggest that the health risks are so grave that PPNs should be banned.5353 Canadian Pharmacists Association. “Canadian Pharmacists Association Calls for Regulation of Payer-Directed Care.” https://www.pharmacists.ca/news-events/news/canadian-pharmacists-association-calls-for-regulation-of-payer-directed-care/.

Conversely, the CLHIA notes that PPN member pharmacies dispensing specialty medications provide an array of valuable patient supports (through manufacturer-funded patient support programs), some of which are otherwise unavailable.5454 Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2024. Submission to the Ontario Ministry of Finance: Consultation on the Preferred Provider Networks in the Employer-Sponsored Drug Insurance Sector. October 22. https://www.clhia.ca/web/CLHIA_LP4W_LND_Webstation.nsf/page/8517732B6CF0E30985258BBE0080951B/$file/ON%20Ministry%20of%20Finance%20-%20PPNs%20in%20Employer-Sponsored%20Drug%20Insurance%20Sector.pdf. These programs provide, among other supports, nurses to inject or infuse biologic drugs, or to train patients how to administer injections at home. They also provide personnel who help the patient claim private and public drug plan reimbursement. Some programs also offer patients financial assistance to reduce their copays (Grundy et al. 2023).5555 Manufacturers are evidently willing to fund these programs, given that they improve patient adherence to their medications and thus increase unit sales volumes. The CLHIA reports high levels of satisfaction among private drug plan beneficiaries who obtain medications from specialty PPNs. I did not find any cases of professional misconduct among Ontario pharmacists related to harms caused by inadequate information sharing in specialty drug PPNs.

The CLHIA also suggests that PPNs expand access to drug coverage by lowering their costs.5656 Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2024. Submission to the Ontario Ministry of Finance: Consultation on the Preferred Provider Networks in the Employer-Sponsored Drug Insurance Sector. October 22. https://www.clhia.ca/web/CLHIA_LP4W_LND_Webstation.nsf/page/8517732B6CF0E30985258BBE0080951B/$file/ON%20Ministry%20of%20Finance%20-%20PPNs%20in%20Employer-Sponsored%20Drug%20Insurance%20Sector.pdf. Specifically, by lowering pharmacy markups on specialty drugs, more insurers will cover these medications, which will ultimately improve patient health. Is this claim accurate? There is survey evidence that employers who sponsor health coverage for their employees are concerned about the cost of health coverage and the cost of drug coverage, in particular.5757 Benefits Canada. 2024. A Perfect Storm: Frontline Perspectives to Help Navigate New Waters for Health Benefits and Wellness Initiatives – The 2024 Benefits Canada Healthcare Survey. Montreal: Benefits Canada. https://www.benefitscanada.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2024/09/BCHS-Report-2024-ENG-Final-WEB.pdf. Smaller insured plans have also dropped specialty drug coverage or imposed annual benefit maximums in the face of growing premiums.5858 Welds, Karen. 2016. “Drug Plan Trends Report: How Drug Plans Are Addressing Skyrocketing Costs.” Benefits Canada. March 18. https://www.benefitscanada.com/benefits/health-benefits/drug-plan-trends-report-how-drug-plans-are-addressing-skyrocketing-costs/. However, there is little evidence on the degree to which the large ASO plans (which cover most private specialty drug costs) would have reduced coverage generosity had PPNs not been introduced.

Because there is limited publicly available empirical evidence on the health risks of closed specialty drug PPNs, it is difficult to assess the claims of the different stakeholders. While the jury is still out on the health risks, I do offer several observations. First, banning all closed PPNs on health grounds is not warranted. Consider a closed PPN that dispenses not just specialty drugs but all drugs. If the PPN member pharmacy becomes the patient’s primary pharmacy, then there would be no fragmentation.

Second, some fragmentation is inevitable. Even if PPNs were banned, some pharmacies would inevitably need to refer their patients to a specialty pharmacy that specializes in intravenous infusion of biologic medications or that has developed specialized clinical expertise in the administration of a particular medication. However, not all specialty drugs need to be provided by specialty pharmacies. Some PPN member pharmacies routinely ship some specialty medications directly to the patient’s home or workplace and provide virtual consultations. These medications evidently do not need special refrigeration or require intravenous infusion. Most SIPs should be able to administer these specialty medications.

Third, if a patient obtains specialty medications from a PPN pharmacy and other medication from a different pharmacy, then problems from fragmentation can be mitigated if caregivers share pertinent clinical information. This is commonplace amongst physicians. General practitioners routinely refer patients to specialists; these physicians then share patient clinical data. A recent example illustrates how this could work in pharmacy.

Pharmacists in Ontario have won the right to diagnose and, if warranted, prescribe medications for health problems that present as minor ailments.5959 Ontario Pharmacists Association. 2025. “Minor Ailments.” https://www.opatoday.com/minorailments/; Canadian Pharmacists Association. “Pharmacists’ Scope of Practice in Canada.” https://www.pharmacists.ca/advocacy/scope-of-practice/. These ailments include both acute problems, such as cold sores, and chronic conditions, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). This policy change occurred despite the protests of physicians, who suggested, inter alia, that this would fragment care.6060 Leighton, Christopher. 2024. “No Minister Jones, Pharmacists Are Not Physicians.” Healthy Debate. September 30. https://healthydebate.ca/2024/09/topic/pharmacists-are-not-physicians/; Ontario Medical Association. 2025. “You Deserve to See a Doctor.” https://www.oma.org/advocacy/you-deserve-to-see-a-doctor/. To avoid problems from fragmentation, pharmacists are required to share information on any prescribed medications with the patient’s primary physician. There have not been any reports of deleterious impacts on patients who have obtained prescription drugs through the minor ailments program. Similarly, provincial pharmacist regulatory bodies could mandate that pharmacies caring for a patient share relevant clinical information. This information sharing would be helpful even if specialty drug PPNs were banned. As noted earlier, even if PPNs were banned, some pharmacies would inevitably need to refer their patients to a specialty pharmacy that specializes in intravenous infusion of biologic medications.

Finally, private drug plan beneficiaries obtaining specialty medications through a PPN might prefer that the PPN be open, not closed. With an open PPN, there is a higher likelihood that they can obtain their medications from their primary pharmacy. An open PPN will presumably be more expensive because specialty pharmacies would see a reduction in sales volumes and would likely charge higher fees in response. Nevertheless, employer sponsored plan beneficiaries may be willing to pay (in terms of forgone money compensation) the additional cost of an open PPN. It is unclear, however, if insurers that offer only closed PPNs have assessed drug plan sponsors’ willingness to pay for an open PPN. If there is reliable evidence of patient harms from closed PPNs, then regulators might consider mandating that insurers offer open PPNs.

Conclusions

For many years, drug insurers in Canada reimbursed pharmacies’ customary fees, passing on these costs to employers and other drug plan sponsors. These fees consist of a percentage markup on drug cost and a dispensing fee. This approach worked well when drug costs were modest. Now, high-cost specialty medications dominate research and development pipelines. The most expensive of these medications costs over $1 million per patient per year. Customary markups on these medications greatly exceed the cost of administering them. Larger drug insurers could presumably unilaterally reduce fees on these drugs. Both large and small insurers have found it more advantageous to establish closed specialty drug PPNs, in which member pharmacies accept lower fees in return for higher patient volumes. This consolidated the administration of these medications in a few specialty pharmacy chains, generating some scale economies, and provided savings to drug plan sponsors.

The growth of closed specialty drug PPNs and the PBMs that administer them attracted the attention of pharmacy stakeholders and regulators. Pharmacy stakeholders have raised the spectre of Canada’s drug benefit system devolving into the US system. In that system, PPNs are routinely used for all medications, corporate concentration is increasing, SIPs are declining, and list prices remain very high. The Competition Bureau has raised similar concerns, while pharmacy regulators have warned about the potential negative impacts of PPNs on patient health. Unfortunately, there has been little evidence to guide policymaking in this area. As Bonnett observes, advocacy relies mainly on “opinions, theories, and American anecdotes.”6161 Bonnett, Chris. 2025. “Preferred Pharmacy Networks – Innovation or Inertia?” Healthy Debate. March 19. https://healthydebate.ca/2025/03/topic/preferred-pharmacy-networks-innovation-inertia/.

Is Canada moving towards a US-style system, as pharmacy stakeholders suggest? My view is that if it is, it has a long way to go to reach the dysfunction of the US system. The reason is that the structural features of Canada’s drug benefits system will avoid most of the problems of the US system. For example, in the US, negotiations between PBMs and drug companies led to rapid growth in both drug list prices and secret rebates paid to PBMs. Rapid drug list price growth is not possible in Canada owing to federal regulations.

My reading of the available evidence suggests that closed specialty PPNs have not adversely affected the financial viability of most SIPs. While current arrangements have reduced SIP participation in the private specialty market, even with PPN bans, most SIPs would generate only a small share of their revenues from serving this market. Moreover, SIPs appear to be more generously reimbursed in Canada than in the US and our commonwealth peers, the UK and Australia. The result is a much higher density of pharmacies in Canada. There is also a higher SIP share of community pharmacies in Canada relative to the US. Given that the specialty medication share of private plan drug spending is increasing, however, it is important to monitor trends in pharmacy sector concentration.

It also appears unlikely that closed PPNs will expand to include non-specialty drugs. In Canada, large employer-sponsored drug plans, including the federal government’s Public Service Health Care Plan, are responsible for most private drug expenditure. Plan beneficiaries evidently value their ability to choose their pharmacy, making further PPN expansions seem unlikely. The savings achievable from expanding PPNs to include all drugs are also smaller.

There is limited evidence on the health impacts of PPNs. Nevertheless, pharmacy stakeholders have expressed concern about the adverse effects of PPNs, owing to the problems that can result from the fragmentation of care. Some have called for PPNs to be banned, arguing that patients should be able to fill all their prescriptions at the same pharmacy. Even if they were banned, however, patients would still require referrals to pharmacies equipped to administer biologics via intravenous infusion. Given that these medications are used by only a small proportion of plan beneficiaries, it is unlikely that every community pharmacy would invest in the necessary infrastructure. As a result, pharmacy regulators might consider requiring pharmacies treating the same patient to share relevant clinical information.

Efforts to regulate PPNs appear to be gathering momentum. The Ontario Ministry of Finance launched a consultation on PPNs in the employer-sponsored drug insurance sector.6262 Ontario Ministry of Finance. “Preferred Provider Networks in the Employer-Sponsored Drug Insurance Sector.” https://www.ontariocanada.com/registry/view.do?postingId=48494&language=en. The Competition Bureau is investigating the PPNs managed by a large PBM, Express Scripts Canada. The Ontario College of Pharmacists intends to sanction pharmacies that participate in closed PPNs, and other provincial regulatory bodies are considering similar policies.6363 Krashinsky Robertson, Susan, and Clare O’Hara. 2024. “Ontario Pharmacists Association Head Applauds Government Study of Preferred Provider Networks.” The Globe and Mail. August 28. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-ontario-pharmacists-association-head-applauds-government-study-of/.

What is clear from my reading of the available evidence is that the remuneration approach that drug benefit providers have used in the past – reimbursing pharmacies’ customary fees – needs reform in the era of specialty drugs. The consultations led by the Ministry of Finance and others, hopefully, will find a low-cost way for insurers, acting as agents for employers and other drug plan sponsors, to negotiate fees with the community pharmacy sector, including SIPs. The consultations will hopefully also explore the barriers that SIPs face in serving the private specialty drug market and whether these barriers might be overcome.

Appendix 1: Estimation of the Fees That Small Independent Pharmacies Could Earn From Dispensing High-Cost Specialty Drugs

I estimate the total remuneration that pharmacies currently accrue from dispensing specialty medications to private drug plan beneficiaries in provinces where PPNs are allowed. The CLHIA reports that in 2023, its member private drug plans spent $15.3 billion on prescribed medications.6464 Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2024. Canadian Life & Health Insurance Facts: 2024 Edition. Toronto: Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. https://www.clhia.ca/facts. Two large PBMs report on the specialty medicine share of this spending. Express Scripts Canada reports that specialty medications accounted for 25.8 percent of the cost of the private drug claims that it processed in 2023;6565 Ibid. Telus reports a 31.2 percent share.6666 TELUS Health. 2024. 2024 Drug Data Trends and National Benchmarks Report. April 23. https://go.telushealth.com/hubfs/telus-health-drug-trends-report-2024-en.pdf?hsLang=en-ca A smaller PBM, operated by the health benefits provider GreenShield, reports a 28.3 percent share.6767 GreenShield. 2024. 2024 GreenShield Drug Trends Report. https://greenshield-cdn.nyc3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/perm/2024/doc/adm_dtr_DrugTrendsReport_nov_7_en_v1.pdf. If we average these percentage shares, then 28.4 percent of medication costs covered by private drug plans, or $4.35 billion, was spent on specialty medications.

To calculate total private spending on specialty medications, beneficiary copayments under private drug plans must be included. A recent study estimated the beneficiary share of this total private spending. This study analyzed a large sample of Canadian private drug plans, covering 167 million prescriptions and $13.5 billion in total prescription costs in 2023 (PMPRB 2025). The study reported the beneficiary-paid share of prescription costs in private drug plans, categorized by the total annual cost of prescriptions filled: less than $5,000; $5,000 to $10,000; $10,000 to $20,000; $20,000 to $50,000; and over $50,000. The beneficiary paid shares were 15.6 percent, 10.9 percent, 8.9 percent, 6.8 percent, and 4.5 percent, respectively – indicating that beneficiary shares are lower the higher the annual cost. For specialty drugs (defined as those costing $10,000 or more annually), the beneficiary share corresponds to some combination of the shares in the top three cost categories. The lowest of these three cost categories does not always capture individuals using specialty drugs, since a beneficiary can incur over $10,000 in drug costs by using several modestly expensive drugs. If the beneficiary share of costs decreases with costs, then the 8.9 percent is likely an overestimate of the beneficiary share of specialty drug costs. Given this, I estimate that beneficiaries contribute 7.5 percent of total specialty drug costs. This implies that total national private plan plus beneficiary spending on specialty medications was $4.7 billion in 2023.

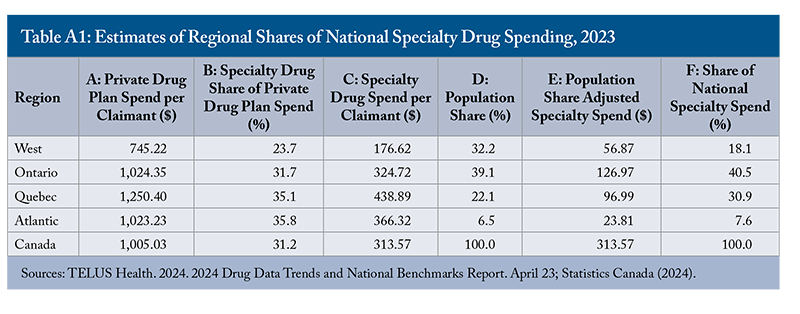

Because Quebec has banned PPNs, we need to remove the Quebec share of this national spending to estimate specialty drug sales in provinces where they are allowed. To do so, I use regional private drug plan spend data for 2023 reported by Telus Health (Table A1).6868 TELUS Health. 2024. 2024 Drug Data Trends and National Benchmarks Report. April 23. https://go.telushealth.com/hubfs/telus-health-drug-trends-report-2024-en.pdf?hsLang=en-ca.

I multiply the drug spend per claimant (column A) by the specialty share of this spend (B) to arrive at specialty drug spend per claimant (C). I then multiply column C by the region’s population share, obtained from Statistics Canada (2024) (D), to arrive at the population share adjusted specialty spend (E). Column F reports the regional share of the national specialty spend. Quebec has a 31 percent share of private drug plan specialty drug spending. By comparison, the recent study of a large sample of Canadian private drug plans reported that Quebec’s share of total privately insured drug costs in 2023 was 28 percent (PMPRB 2025). Removing this 31 percent share of the $4.7 billion national spending implies $3.243 billion in private specialty drug sales in the rest of Canada. By way of comparison, $7.4 billion (or 43.3 percent) of the $17.2 billion in national public drug program spending in 2022 was spent on specialty drugs.6969 Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2023. Prescribed Drug Spending in Canada, 2023. Ottawa, ON: CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/en/prescribed-drug-spending-in-canada-2023. If we add beneficiary copayments, estimated to be 15 percent of total drug costs, then the total cost of specialty drugs reimbursed by public plans was $8.7 billion.

Most of this $3.2 billion private specialty drug spend accrues to specialty drug manufacturers (at least prior to the payment of off-invoice rebates); the remainder accrues to pharmacies in the form of markups and dispensing fees. Estimates of the pharmacy share come from an analysis of claims that a large national private drug plan paid in 2022.7070 Reformulary Group. 2023. Cost of a Private Drug Plan Claim. Ottawa: Reformulary Group. August 23. https://innovativemedicines.ca/resources/all-resources/cost-of-a-private-drug-plan-claim/. This was done separately for pharmacies in Quebec and in the rest of Canada, and for drugs whose annual total cost was under $10,000, $10,000-$24,999, $25,000-$99,999, and $100,000 and over. Pharmacies outside Quebec accrued 26.4 percent, 11.4 percent, 12.3 percent, and 11.1 percent, respectively, of the prescription cost in each of the four categories. (The pharmacy share was markedly higher in Quebec). The pharmacy share of specialty drug costs is likely somewhere between 11.1 percent and 12.3 percent, perhaps at 11.7 percent.

It is unclear if this 11.7 percent captures all markup discounts that specialty PPN pharmacies provide to payers. The reason is that an analysis of private plan claims data from 2015, prior to the widespread use of PPNs, found that the average markup on high-cost drugs was 12.1 percent (Gagnon-Arpin et al. 2018). One would expect the markup charged by PPNs in 2023 to be markedly lower than 12.1 percent. This suggests that the 11.7 percent is likely an upper bound.

Multiplying this 11.7 percent by the $3.243 billion yields $379 million in pharmacy fees for specialty drugs dispensed outside Quebec and reimbursed by private plans and their beneficiaries in 2023. This is a substantial sum, but the impact needs to be considered in light of total pharmacy dispensing revenues. According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, total prescription drug spending outside of Quebec in 2023 was estimated as $31.2 billion.7171 Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2024. “National Health Expenditure Trends, 2024: Table G.14.1 – Expenditure on Drugs by Type and Source of Finance in Millions of Current Dollars, Canada, 1985 to 2024.” Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-health-expenditure-trends. Using 21 percent as a conservative estimate of the pharmacy share of this spending yields pharmacy fees of $6.56 billion. Remuneration for vaccinations, medication review, and other publicly funded services outside Quebec in 2023 was around $0.5 billion, bringing total remuneration for core pharmacy services to $7 billion.7272 Canadian Foundation for Pharmacy. 2025. “CFP Services Chart: Services, Fees and Claims Data for Government-Sponsored Pharmacy Programs.” CFP. https://cfpnet.ca/publications/provincial-services-chart. (This revenue excludes margins earned on the sale of over-the-counter drugs, personal health products, and other merchandise and rebates paid by generic drug manufacturers). Pharmacy remuneration for specialty drugs outside Quebec is thus about 5.4 percent (0.379/7) of core pharmacy revenue.

References

Barnes, Steve, and Laura Anderson. 2015. Low Earnings, Unfilled Prescriptions: Employer-Provided Health Benefit Coverage in Canada. Toronto: Wellesley Institute. https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Low-Earnings-Unfilled-Prescriptions-2015.pdf.

Chamoun, M., A. Forget, I. Chabot, M. Schnitzer, and L. Blais. 2022. “Difference in Drug Cost between Private and Public Drug Plans in Quebec, Canada.” BMC Health Services Research 22 (1): 200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07611-4.

Costa, Joan, and Jaume García. 2003. “Demand for Private Health Insurance: How Important Is the Quality Gap?” Health Economics 12 (7): 587–599. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.756.

Dickson, Sean R., Nico Gabriel, Walid F. Gellad, et al. 2023. “Assessment of Commercial and Mandatory Discounts in the Gross-to-Net Bubble for the Top Insulin Products From 2012 to 2019.” JAMA Network Open 6 (6): e2318145. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18145.

Gagnon-Arpin, I., R. Vroegop, and T. Dinh. 2018. Health Care Aware: Understanding Pharmaceutical Pricing in Canada. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/e-library/abstract.aspx?did=9897.

Grootendorst, Paul. 2024. “Florida Wants to Import Low-Cost Prescription Drugs from Canada. Will Its Plan Work?” Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI) 9 (1): 486–490. https://hmpi.org/2024/04/12/florida-wants-to-import-low-cost-prescription-drugs-from-canada-will-its-plan-work/.

Grundy, Quinn, Ashton Quanbury, Dana Hart, Shanzeh Chaudhry, Farideh Tavangar, Joel Lexchin, Marc-André Gagnon, and Mina Tadrous. 2023. “Prevalence and Nature of Manufacturer-Sponsored Patient Support Programs for Prescription Drugs in Canada: A Cross-Sectional Study.” CMAJ 195 (46): E1565–E1576. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.230841.

Guadamuz, Jenny S., G. Caleb Alexander, Genevieve P. Kanter, and Dima Mazen Qato. 2024. “More US Pharmacies Closed Than Opened in 2018–21; Independent Pharmacies, Those in Black, Latinx Communities Most at Risk.” Health Affairs 43 (12): 1703–11. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2024.00192.

Health Canada. 2019. A Prescription for Canada: Achieving Pharmacare for All. Final Report of the Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare. Ottawa: Government of Canada. June. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/implementation-national-pharmacare/final-report.html.

Martin, Kristi. 2025. “What Pharmacy Benefit Managers Do, and How They Contribute to Drug Spending.” Commonwealth Fund. March 17. https://doi.org/10.26099/fsgq-y980.

McCauley, Kelly. 2024. Changeover of the Public Service Health Care Plan from Sun Life to Canada Life. Report of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates, 44th Parliament, 1st Session. Ottawa: House of Commons. June. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/441/OGGO/Reports/RP13116720/oggorp20/oggorp20-e.pdf.

O’Brady, Sean, Marc-André Gagnon, and Alan Cassels. 2015. “Reforming Private Drug Coverage in Canada: Inefficient Drug Benefit Design and the Barriers to Change in Unionized Settings.” Health Policy 119 (2): 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.013.

Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB). 2025. Private Drug Plans in Canada: Expenditure Report, 2018–2023. National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System. Ottawa: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. February. https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/npduis/analytical-studies/private-drug-plans-2018-2023.html#app-c.

Pukhov, Olexiy, Alexander Hoagland, and Paul Grootendorst. 2025. “The economics of community pharmacy in Canada. Part 1: Overview and empirical analysis of community pharmacy strategies in Ontario.” Canadian Pharmacists Journal, forthcoming.

Statistics Canada. 2024. “Population estimates on July 1, by age and gender.” Table 17-10-0005-01. September 25. https://doi.org/10.25318/1710000501-eng.

The views expressed here are those of the author and are not attributable to their respective organizations. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

Related Publications

- Intelligence Memos